Managing invasive tree stumps in the restoration of legacy chestnut orchards

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 18, Issue 6, Pages 350-356 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor4799-018

Published: Nov 30, 2025 - Copyright © 2025 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

The removal of tree stumps is an important component in field recultivation, park management, and land development (or restoration). Mulching the stumps to ground level is a fast and effective solution that minimizes soil disturbance and avoids the burden of rootstock disposal typically incurred when uprooting the stumps. This study reports on the productivity and cost of mulching tree stumps using a light, remote-controlled tool carrier (36 kW) equipped with a dedicated forestry mulcher. The new machine was used for grinding the stumps of invasive alder trees in a legacy chestnut orchard restored to production. Mulching proved fast and effective. The light machine ground over 60 stumps (diameter approximately 30 cm) per scheduled machine hour (SMH), treating a hectare in less than 3.5 SMH. This translated into a treatment cost of 202 € ha-1. Regression analysis yielded an equation for estimating grinding time as a function of stump volume. Using this equation and estimating the existing number of stumps per hectare, operators can easily calculate the productivity and cost of each given job.

Keywords

Introduction

Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) orchards have characterized the economic and social history of the Italian mountains for many centuries, ensuring the subsistence and prosperity of local populations against a challenging natural environment ([11], [5]) and representing a classical model of an agroforestry system ([18]). At the beginning of the 20th century, Italian chestnut groves covered approximately 800.000 ha and produced 600.000 tons of chestnuts per year. Chestnuts alone accounted for almost 20% of the value generated by all Italian forests at the time ([2]). The advent of various diseases (e.g., chestnut blight, canker, Asian gall wasp, etc.) and the rapid economic and social changes in the country have led to an unstoppable decline in chestnut cultivation and culture. By 1930, the surface area of chestnut orchards had fallen to about 500.000 ha and production to 400.000 tons per year. In 1970, chestnut orchards covered only 145.000 ha, and today they remain on just over 30.000 ha ([15]). However, the chestnut heritage handed down to us still holds new possibilities. In particular, demand for chestnuts and chestnut products remains high and is currently increasing, partly due to new efforts to overcome the limitations of seasonal consumption ([16]). Italy is the first producer and the first exporter of chestnut products in Europe, and the second in the World after China ([13]); therefore, there is an interest in reviving national production through the establishment of modern intensively managed orchards and the restoration of abandoned legacy orchards that are still a pervasive feature of the mountain landscape of many Italian regions ([20]).

The restoration of abandoned legacy groves requires several actions, including the removal of invasive species that rapidly colonize those widely spaced stands after tending is discontinued ([8]). Within a few decades, the orchard becomes a mixed stand, with the old giants surrounded by fast-growing trees such as alder or birch ([3]). The removal of the invasive trees is straightforward and conducted with conventional logging techniques and equipment. In fact, this is the only step in the restoration process that can yield some profit. However, cut tree stumps must be removed to mechanize orchard management, as they pose an obstacle to machine traffic and operations. Neither a mulcher nor a modern nut harvester can operate efficiently if they need to maneuver around old stumps, which makes de-stumping a key enabler of modernization.

To date, stump disposal has been based on uprooting with an excavator or grinding with a mechanical drill ([24], [25]). While the latter is a more surgical and less destructive approach than the former, they both cause significant soil disturbance ([7]), which inevitably leads to soil nutrient losses ([9], [19]). Improved soil structure and richer soil fauna are the only benefits of pausing orchard management, which are immediately lost when de-stumping is conducted using either of the two techniques mentioned above. In fact, there is no need to remove the entire rootstock if the primary goal of the operation is to enhance trafficability: bringing the stump down to ground level is enough to remove the hindrance. In contrast, stump resprouting is rare and can be easily controlled by mulching the eventual shoots once or twice. Dedicated stump grinders already exist and are widely used in gardening, but these machines are relatively slow and typically deployed only to reduce scattered stumps ([26]).

In contrast, the reduction of invasive stumps is a field operation that treats hundreds of stumps per hectare. It must proceed quickly to meet the cost limitations of most agricultural practices. In this case, a heavy forest mulcher might offer a better alternative, and this was the equipment considered for this study. In turn, the type of mulcher selected for chestnut orchards had to be light enough to be moved on a light transport, given that most Italian chestnut farms are small ([10]) and the operation might require frequent relocation. A further benefit of adopting a light, agile machine is reducing soil compaction, which increases sensitivity to root disease ([14]).

In this study, we tested a high-mobility mini-crawler fitted with a robust forest mulcher capable of chewing stumps to ground level. The main goals of the study were to determine the efficiency of this new system and to estimate reference values for its key performance indicators, such as work productivity, fuel consumption, operating costs, and work quality.

Materials and methods

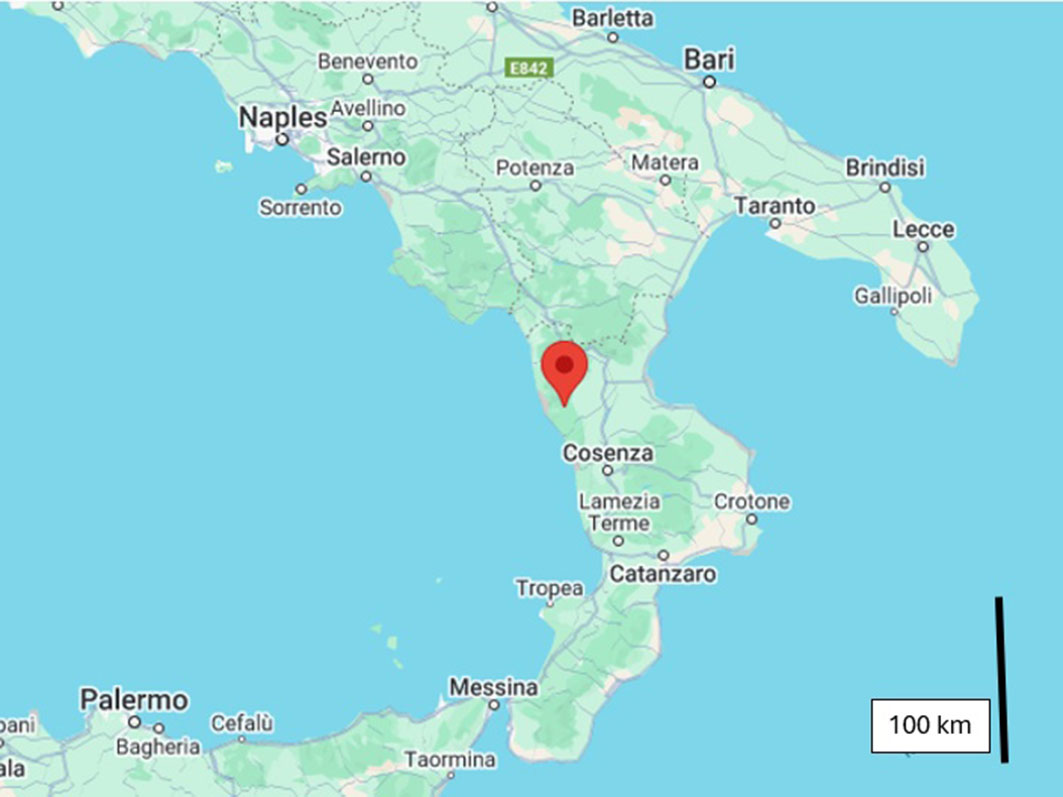

A 2-day trial was conducted on November 19th and 20th, 2024. The trial was conducted in the pilot orchard installed by the National Research Council of Italy (CNR) and the University of Florence at Palummaro (Pidgen Loft, 634 m a.s.l., GPS coordinates 39° 36′ 13.4″ N, 15° 59′ 16.5″ E) in the municipality of Sant’Agata d’Esaro (Cosenza), Southern Italy (Fig. 1). The site is located in the Calabrian coastal range, which offers ideal conditions for chestnut cultivation. For centuries, many villages in the surrounding area thrived on chestnut farming and were reputed producers and exporters of chestnuts ([4]). This legacy is still evident in the many abandoned and semi-abandoned orchards in the landscape, where majestic old trees are surrounded by thick undergrowth consisting of alder, cherry, and oaks.

The pilot orchard is located on a hill, on even, gently sloping terrain (mean slope gradient = 16%), hence the interest in mechanizing all operations. It measures 1.51 ha and contains 46 original chestnut trees with diameters at breast height (DBH) ranging from 100 to 220 cm. The age of those trees was not determined, but it must amount to over a century. Restoration of the old semi-abandoned orchard was initiated in January 2023, by removing over 350 Italian alder (Alnus cordata Loisel.) trees, with a DBH between 12 and 40 cm. The old, dead chestnut trees were cut and removed (n = 8) while the living ones were pruned. The clearings were planted with new chestnut trees (n = 60), and good-quality wildings were grafted with the local nut cultivar. The old fence was replaced to prevent browsing damage and protect the scientific instruments installed on site (weather station, cameras, dendrometers, etc.). The next step was removing the many alder stumps that had died without resprouting, but still hindered mulching the aggressive fern (Pteridium aquilinum L.) undergrowth and mechanical harvesting.

The machine used for the test was the RoboFifty RS, a fully hydraulic tracked tractor, powered by a 36 kW (50 HP) Perkins Stage V turbocharged engine and equipped with a front quick hitch capable of accommodating dozens of different tools (⇒ https://en.energreen.it/the-new-robofifti/). The machine has a very low center of gravity and can work on slopes up to 55° (140%), thanks to an innovative lubrication system that ensures adequate draft even on extreme slopes. The wide rubber tracks (28 cm) allow it to travel on and off-road and minimize ground pressure, effectively preventing soil compaction. Modest size (2030 × 1310 × 1135 mm) and low weight (1200 kg) allow for transportation on a standard van, making it easier to move between working sites. Once on the ground, the machine is driven via a remote control within a 150 m range and can reach a maximum speed of 7 km h-1.

For the test, the machine was equipped with the Energreen 130T forestry mulcher, featuring a rotor with 32 fixed teeth arranged in a helical sequence to ensure an even workload. Each of the 32 interchangeable teeth is coupled with an adjustable cut depth limiter to maintain an even work pace. The 130 T mulcher has a working width of 110 cm and weighs 390 kg, so that the machine used at Pidgeon Loft had a total weight of 1600 kg, which is half the weight of the alternative, i.e., a farm tractor with a conventional forestry mulcher. For all the duration of the test, the machine was operated by Energreen’s own test and demo driver, an experienced professional with all the required formal qualifications (Fig. 2).

Before starting the trial, all stumps were assigned ID numbers, which were written on the cut faces using high-visibility permanent paint for easy identification during the test. A researcher determined the species, diameter, and height above the ground of each stump, using a ruler. The recorded diameter was the average of two measurements taken at 90° apart, while the height was the average of three measurements. When the stump brought evidence of multiple stems deriving from some earlier coppicing, the measurements were taken separately for each of the stubs, so that the ID record contained multiple diameters and heights based on the number of stubs visible on the cut stump (often inferred by the separate year ring cores). Stumps were visually inspected for exterior signs of decay and scraped with a pocketknife when decay was suspected (e.g., cut face covered with fungi, heavy discoloration, etc.).

During the trial, a researcher recorded the time taken to grind each marked stump down to ground level ([17] - Fig. 3). The treating of one stump was the observation unit and the time required (i.e., work cycle time) was divided into the following tasks (i.e., work time elements): maneuvering (as the tractor often maneuver around the stump to approach it from the most suitable direction) and grinding (the time the mulcher actually engaged the stump, indicated by the distinctive noise and the projection of chips). The delay time was kept separate and excluded from the analysis, given that the short observation time could not provide a fair representation of its actual impact. A 25% delay factor was used instead ([23]). Work time was determined using a classic mechanical time-study board and by observing footage recorded during the work. All time records were associated with the respective stump IDs.

Machine costs were calculated with the method developed within the scope of COST Action FP0902 ([1]). Costing assumptions (investment cost, service life, maintenance) were obtained directly from the manufacturer. In contrast, fuel cost was determined by starting the trial with a full tank and refueling after the test. Labor cost was assumed to be 20 euros per scheduled machine hour (SMH), according to the approved regional price lists (Tab. 1).

Tab. 1 - Cost calculation. (SMH): Scheduled machine hour, including 20% delays (i.e., delay factor = 25%); lubricant cost estimated as 10% of fuel cost; maintenance cost estimated at 50% of investment cost; overheads and profit estimated as 20% of net total.

| Group | Characteristics | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assumptions | Investment | € | 60,000 |

| Service life | years | 8 | |

| Annual use | SMH | 1,000 | |

| Salvage value | % investment | 30 | |

| Interest | % | 4 | |

| Insurance | € year | 2,500 | |

| Fuel consumption | L SMH-1 | 9.3 | |

| Fuel price | € L-1 | 1.6 | |

| Crew | n | 1 | |

| Labour cost | € SMH-1 | 20 | |

| Calculations | Capital cost | € SMH-1 | 9.4 |

| Fuel cost | € SMH-1 | 14.9 | |

| Lubricant cost | € SMH-1 | 1.5 | |

| Maintenance cost | € SMH-1 | 2.6 | |

| Personnel cost | € SMH-1 | 20.0 | |

| Overheads and profit | € SMH-1 | 9.7 | |

| Total cost | € SMH-1 | 58.1 |

Data analysis consisted of extracting simple descriptive statistics to provide solid indicators of centrality and variability. Then, regression analysis was used to check the statistical significance of the relationships between time consumption and stump characteristics (diameter, height, etc.). The effect of species difference was tested by introducing an indicator variable for hard stumps (exclusively chestnut). The chosen significance level was α = 0.05.

Results

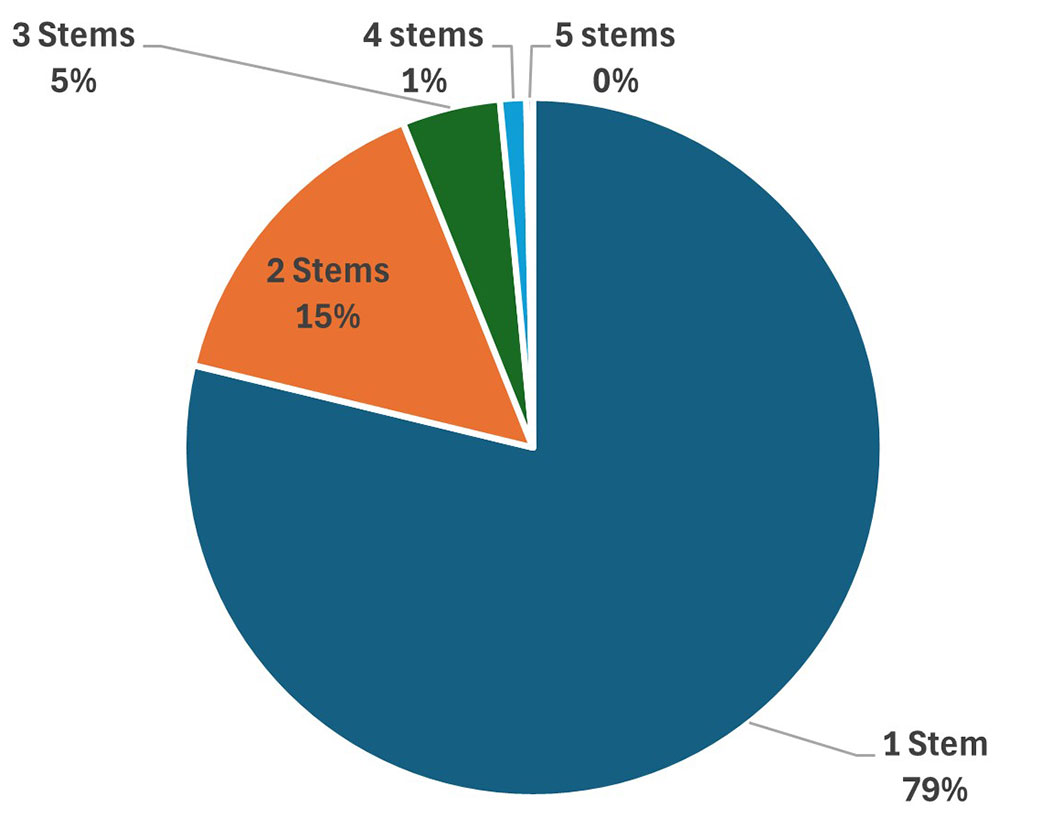

The majority (79%) of the cut stumps showed evidence of carrying a single stem, indicating that the invasive alder was in its pristine condition at the time of removal and had not been coppiced previously (Fig. 4, Tab. 2). The few instances of multiple stems might result from browsing damage or occasional opportunistic cuts made by the previous tenants and/or passing shepherds. Mean stump height was reasonably close to the ground and matched the prescribed good cutting practice. Cutting much closer to the ground could dramatically increase saw-tooth wear and incur an excessive risk of saw damage. Stump size was consistent with that of alder trees aged 15-20 years. The few huge stumps were, in fact, multi-stem clumps that were cut below the insertion of the stems. A moderate diameter and low cutting height resulted in a relatively small volume of wood to be ground, with the majority of stumps falling within the 12-liter volume limit (upper quartile). The preliminary inspection detected only very few cases of severe decay, and those stumps were excluded from the study. They were not numbered and the researchers smashed them to ground level with their boots. Observation during the test confirmed the absence of severely decayed stumps, which would otherwise have been detected by a different sound (hammers hitting soft rather than solid wood) and by the shape and size of the wood chips. This would not exclude various subtler degrees of “softening” that occurred during the 22 months the stumps were left on the ground after cutting.

Tab. 2 - Stump characteristics. Measurement referred to the above-ground portion, only; (Mean D): mean of the diameters of all stubs on the stump if they are more than one; (Max D): diameter of the largest stub on the stump if the stump carries more than one stub; (Std Dev): Standard deviation; (LQ): Lower quartile (25%); (UQ): Upper quartile (75%).

| Stats | Height (cm) |

Mean D (cm) |

Max D (cm) |

Stub (n) |

Volume (cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 330 | 330 | 330 | 330 | 330 |

| Mean | 7.4 | 29.0 | 29.9 | 1.5 | 8,122 |

| Std Dev | 3.9 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 1.0 | 8,782 |

| Std Error | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 544 |

| min | 1 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 177 |

| Max | 24 | 80 | 80 | 9 | 61,588 |

| Median | 7 | 29 | 30 | 1 | 5,445 |

| LQ | 4 | 19 | 20 | 1 | 3,505 |

| UQ | 9 | 33 | 34 | 1 | 12,738 |

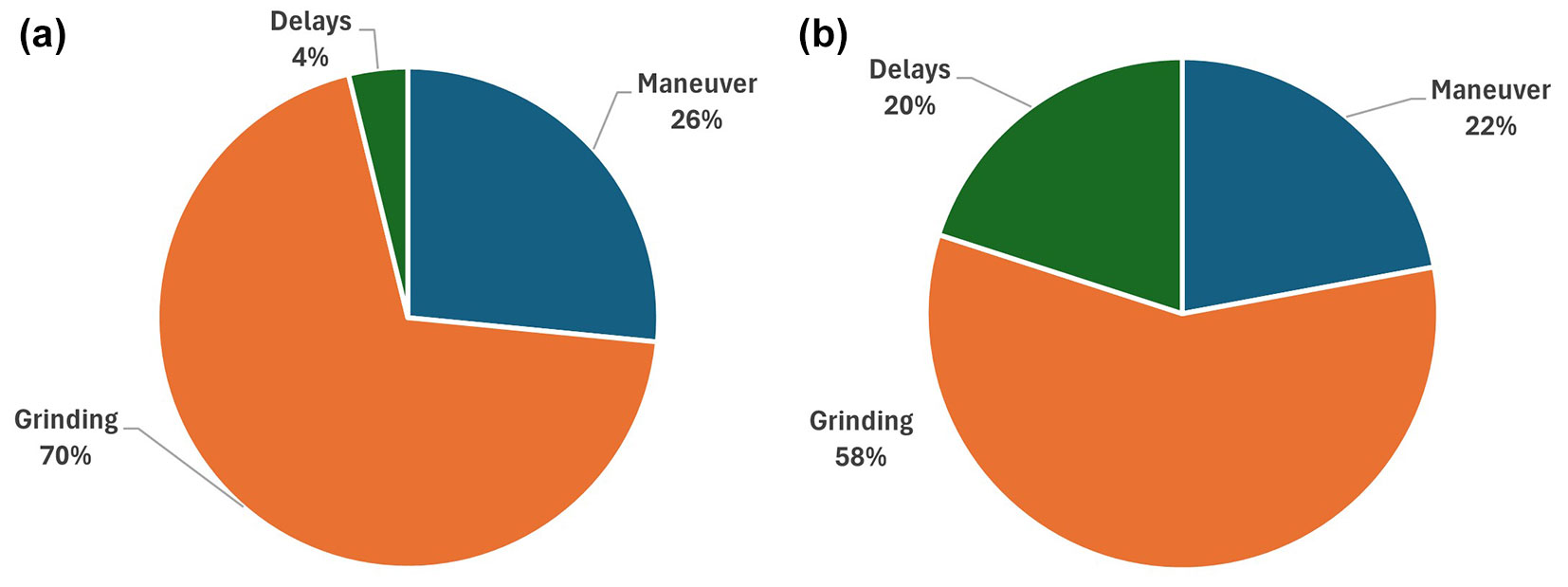

The average net work cycle was 53 s per stump, excluding delays (Tab. 3). This time varied most commonly between 11 s and 61 s per stump (interquartile range). Actual grinding time accounted for 70% or 58% of the total worksite time, depending on whether we accept the unusually low incidence of delay time recorded during the study (4%), or if we correct that value with one (20%) that is more likely to reflect long-term operation (Fig. 5). In both cases, the very moderate incidence of maneuvering time points to good tactical planning, as the driver wisely plans the sequence of stumps to be treated to minimize unnecessary maneuvers.

Tab. 3 - Time consumption (s) for the main productive tasks. (Maneuver): the time the machine maneuvers to approach the target stump; (Grind): the actual grinding time, when the working tool engages the stump; (Net work): the sum of the two; (Mean): mean value based on the number of events, not cycles (i.e. maneuver does not appear in all cycles and the mean is based on appearances - the value would be lower (and the min would be 0) if the mean was based on the number of cycles. (Std Dev): Standard deviation; (LQ): Lower quartile (25%); (UQ): Upper quartile (75%),

| Stats | Maneuver | Grind | Net work |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 197 | 280 | 280 |

| Mean | 21 | 39 | 53 |

| Std Dev | 19 | 52 | 56 |

| Std Error | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| min | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Max | 139 | 468 | 475 |

| Median | 16 | 23 | 39 |

| LQ | 6 | 11 | 10 |

| UQ | 36 | 61 | 88 |

Fig. 5 - Distribution of worksite time by activity type. Distribution actually measured during the study (a) and simulated for a more realistic incidence of delays estimated at 20% of the total (b).

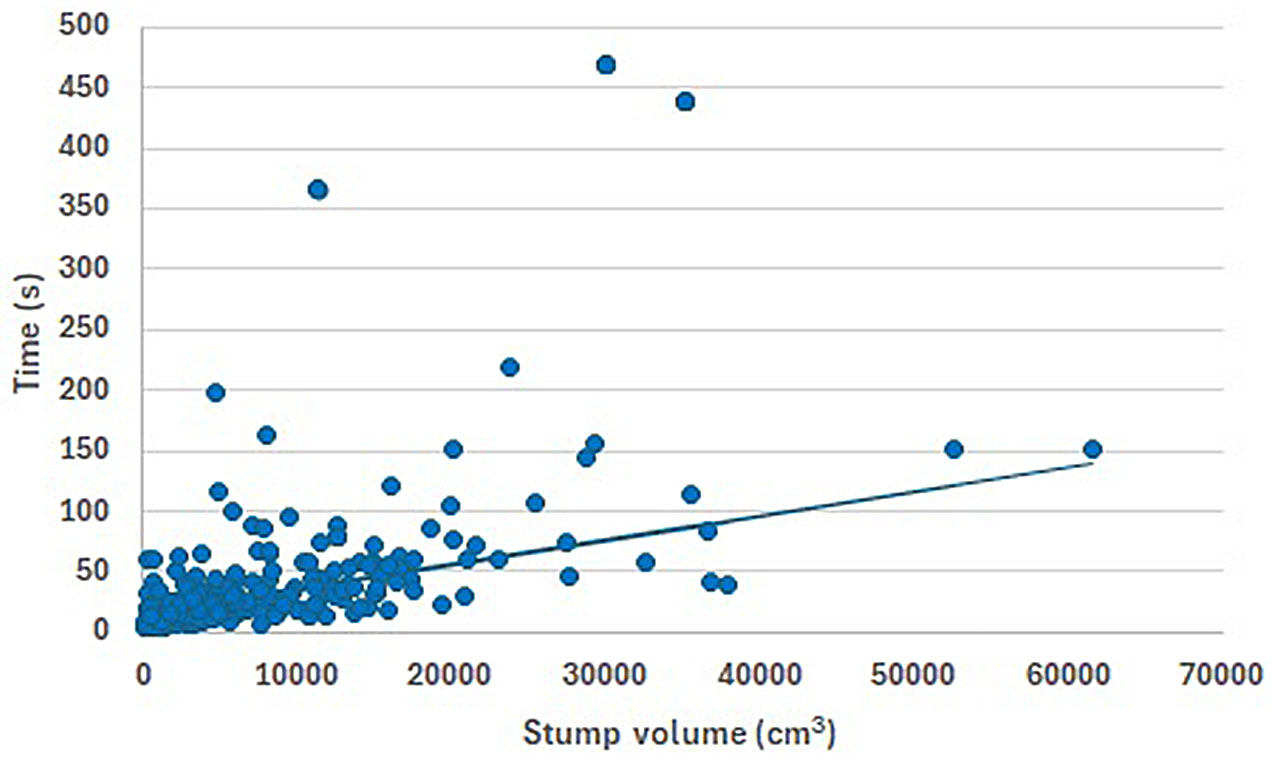

Fig. 6 - Grinding time (Y axis) as a function of above-ground stump volume (X axis): scattergram and compensated graph.

Tab. 4 - Regression equation for grinding time (s) as a function of stump volume and species. (s): grinding time in seconds; (Vs): stump volume (cm3); (S): indicator (dummy) variable for chestnut: chestnut = 1 if the stump is chestnut, chestnut = 0 if the stump is alder; (n): number of valid datapoints (observations).

| Grinding time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s = a + b·Vs + c·Vs·S | ||||

| (adj-R2 = 0.686, n = 261) | ||||

| Parameter | Coefficient | Std Error | t-value | p-value |

| a | 16.093 | 2.528 | 6.365 | <0.0001 |

| b | 0.002 | 2.1 e-4 | 10.818 | <0.0001 |

| c | 0.011 | 0.001 | 17.974 | <0.0001 |

Assuming a 20% incidence of delays and a stump density of 213 units per hectare, as in the case of the test orchard, the productivity reaches 61 stumps per scheduled machine hour (SMH) or 0.29 ha SMH-1. This translates into a daily productivity of 2.31 ha and a treatment cost of 202 € ha-1. Indeed, productivity and cost depend on stump size, because time consumption is logically proportional to the volume of wood that needs grinding. Regression analysis revealed a significant association between net grinding time and stump size indicators, such as stump height, stump diameter, and especially stump volume. Given that the latter indicator was the strongest predictor and the easiest to use, we have reported the compensated scatter plot (Fig. 6) and the regression table (Tab. 4) for the function (eqn. 1):

where tg is the grinding time (s), Vs is the stump volume (cm3), and S is the species. The equation is highly significant and accounts for more than 60% of the total variability in the data pool.

Fuel consumption amounted to 48 L of diesel fuel in 4.16 net work hours, or 11.2 L per working hour. Assuming a delay incidence of 20% of total time (or 25% of net work time), total worksite time amounts to 5.12 scheduled machine hours (SMH) and fuel consumption to 9.3 L SMH-1.

Discussion

Before attempting a meaningful discussion of the study results, it is crucial to address the main limitations of this study, and especially its short duration. This makes it challenging to offer an accurate representation of delay time, which had to be estimated based on general figures, as is often done in similar studies. Therefore, the study results may not accurately reflect the machine’s reliability on test, which may achieve a higher or lower utilization than the general benchmark used in the study. On the other hand, the study duration seemed adequate for modeling net work time, as it allowed capturing over 250 valid observations in which accurate time-use data could be associated with accurate stump-size measurements.

Unexplained variation in the data pool may be partly attributed to the different degrees of decay of the treated stumps, which must have been somewhat “softened” during the 22 months elapsed after cutting. If not extremely severe, such an effect would escape visual and tactile observation and should be gauged through drilling or penetration tests. Future research might explore the capacity of quick wood hardness testing systems to attach a decay indicator to each stump before grinding. Nevertheless, the benchmark figures and the prediction model obtained through this experiment have a reasonable predictive capacity and remain quite valuable for managing restoration work, though they could be further refined. In particular, our study could not account for the effect of variable stump density (i.e., stumps ha-1), which can contract or expand maneuvering time, thus affecting performance to some extent.

The study demonstrates that stump grinding can proceed quickly and that a smooth ground surface can be restored at relatively little cost. Such encouraging results are partly due to alder wood’s low durability, which is likely to soften after 22 months in the ground. In fact, the density and hardness (Janka test) of sound alder wood are only slightly lower than those of chestnut: 560 kg m-3 vs. 590 kg m-3 and 295 kgf vs. 308 kgf for alder and chestnut, respectively ([22]). What changes most is durability: it is very low for alder and very high for chestnut. This may explain why grinding required 2 s L-1 with alder stumps and approximately 13 s L-1 with chestnut stumps. The question then arises: how common is it to wait over 1 year after cutting before grinding alder stumps? On one hand, if the machine used for extracting the alder trees could be easily equipped with a mulcher, it would make sense to switch implements once extraction is completed and use the same machine to grind the stumps, thus saving on machine relocation cost. On the other hand, there is little need to grind the stumps straight away, since the next harvest will come in over a year after cutting the invasive trees, because the old chestnut trees have to be pruned first. They will need to rebuild their crowns before yielding any significant amounts of nuts. Besides, when the grinding machine has the same general characteristics as the mini-crawler on test, relocation would be fast and inexpensive.

Alder is not the only pioneer species to often invade abandoned or poorly managed chestnut orchards. Depending on the pedo-climatic conditions, other species can colonize the orchard (e.g., birch). Although they may differ in some aspects, these species generally exhibit characteristics similar to alder, such as rapid growth, early aging, and low wood durability. Therefore, it is reasonable to cautiously apply the findings from this study to these species as well, along with the suggested management strategy of delaying grinding.

In general, the fact that the stumps of those invasive species can be ground with relative ease should reinforce the option of grinding rather than uprooting. The latter might become a viable contender with hard, durable wood. Even then, the heavy soil disturbance caused by uprooting and the complexity of disposing of rootstock should still be considered.

There are two main alternatives to the mini-crawler when it comes to stump grinding. The first is to use a walk-behind motor-manual root grinder designed for gardening. Such a machine is much cheaper and can still do the job, but it is also much slower and less agile. Moreover, the ergonomics of motor-manual grinders are questionable at best ([27]) and are not suitable for prolonged, continuous use. The second alternative is the tractor-mounted stump drill, which may effectively crush the stump and rootstock down to 100 cm below ground ([12]). Such a machine is designed for industrial plantations and is very productive, as it can treat over 200 stumps per hour (net time, excluding delays - [21]). However, performance quickly degrades as work conditions worsen due to the farm tractor’s relatively poor mobility. In challenging terrain, it may be best to fit the stump drill to an excavator, which is more agile and can be positioned with reasonable accuracy on scattered stumps that are not aligned with a main direction. The drill could be a viable alternative when dealing with hard stumps, because its working principle is actually splitting - not grinding - and requires less energy to achieve the same result, partly because the stump is broken down into coarser fragments. The use of stump drills in chestnut restoration work could be addressed in future research and may be viable when the stumps to be treated are not adjacent to live chestnut trees; otherwise, drilling might injure the live tree’s roots and promote infection.

Conclusions

Among all de-stumping options, a mulcher-equipped mini-crawler is the most promising, as it can avoid soil disturbance and navigate the most challenging terrain without putting the operator at risk. Furthermore, most mini-crawlers can be equipped with a variety of tools to assist with many other orchard management tasks, such as pre-harvest undergrowth reduction and nut harvesting (⇒ https://www.alpirobot.com/), or to perform those logging jobs once performed by the increasingly rare work animals ([6]). Finally, this study demonstrates that mechanization must not be considered solely as a way to reduce management costs, but rather as a key enabler of better management practices. The reduction in de-stumping expenses is a significant advantage, but it is not the main benefit offered by the mini-crawler. Disposing of stumps without degrading the original soil structure and quality is indeed a far more critical goal, and one that other technology solutions cannot achieve to the same degree.

References

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Natascia Magagnotti 0000-0003-3508-514X

CNR Institute of Bioeconomy, v. Madonna del Piano 10, Sesto Fiorentino, FI (Italy)

Marcello Biocca 0000-0002-2718-7907

CREA Consiglio per la ricerca in agricoltura e l’analisi dell’economia agraria - Research Centre for Engineering and Agro-Food Processing, v. della Pascolare 16, Monterotondo, RM (Italy)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Spinelli R, Magagnotti N, Gallo P, Biocca M (2025). Managing invasive tree stumps in the restoration of legacy chestnut orchards. iForest 18: 350-356. - doi: 10.3832/ifor4799-018

Academic Editor

Rodolfo Picchio

Paper history

Received: Jan 21, 2025

Accepted: Jun 16, 2025

First online: Nov 30, 2025

Publication Date: Dec 31, 2025

Publication Time: 5.57 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2025

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 1489

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 583

Abstract Page Views: 438

PDF Downloads: 395

Citation/Reference Downloads: 0

XML Downloads: 73

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 100

Overall contacts: 1489

Avg. contacts per week: 104.23

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

(No citations were found up to date. Please come back later)

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Characterization of VOC emission profile of different wood species during moisture cycles

vol. 10, pp. 576-584 (online: 08 May 2017)

Research Articles

Deploying an early-stage Cyber-Physical System for the implementation of Forestry 4.0 in a New Zealand timber harvesting context

vol. 17, pp. 353-359 (online: 13 November 2024)

Research Articles

Modifying harvesting time as a tool to reduce nutrient export by timber extraction: a case study in planted teak (Tectona grandis L.f.) forests in Costa Rica

vol. 9, pp. 729-735 (online: 03 June 2016)

Research Articles

Density, extractives and decay resistance variabilities within branch wood from four agroforestry hardwood species

vol. 14, pp. 212-220 (online: 02 May 2021)

Research Articles

Identification of wood from the Amazon by characteristics of Haralick and Neural Network: image segmentation and polishing of the surface

vol. 15, pp. 234-239 (online: 14 July 2022)

Research Articles

Comparison of alternative harvesting systems for selective thinning in a Mediterranean pine afforestation (Pinus halepensis Mill.) for bioenergy use

vol. 14, pp. 465-472 (online: 16 October 2021)

Research Articles

NIR-based models for estimating selected physical and chemical wood properties from fast-growing plantations

vol. 15, pp. 372-380 (online: 05 October 2022)

Research Articles

Study on the chemical composition of teak wood extracts in different organic solvents

vol. 14, pp. 329-336 (online: 09 July 2021)

Research Articles

Examining the evolution and convergence of wood modification and environmental impact assessment in research

vol. 10, pp. 879-885 (online: 06 November 2017)

Research Articles

Physical, chemical and mechanical properties of Pinus sylvestris wood at five sites in Portugal

vol. 10, pp. 669-679 (online: 11 July 2017)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword