Comparison of alternative harvesting systems for selective thinning in a Mediterranean pine afforestation (Pinus halepensis Mill.) for bioenergy use

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 14, Issue 5, Pages 465-472 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor3636-014

Published: Oct 16, 2021 - Copyright © 2021 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Due to a continuous abandonment of marginal agricultural land, Mediterranean pine forests are growing both in biomass stock and area but remain mainly unmanaged. Pinus halepensis is one of the main pioneer species with strong expansion throughout the Mediterranean basin. In mature forests and pole stands, selective thinnings aimed to eliminate dominated and dead trees are necessary to improve the resilience and persistence of these forest ecosystems. Bioenergy market provides an opportunity to mobilise this woody material, helping to prevent and reduce wildfires in a context of climate change and energy transition. Despite the existing expertise on wood harvesting, there is a lack of practical knowledge about cost-effective methods for bioenergy use of selective thinnings in such forests. The objective of this study was to compare thinning harvesting methods in representative 63-year-old Pinus halepensis afforestation in pole stage for bioenergy uses, following the silvicultural treatments defined in the Spanish forest management plan. Time studies were performed over six representative plots in Navalón (Spain). Treatments included three plots with the traditional stem wood method combined with the logging of forest residues (integrated system), and three plots with the whole tree chipping (whole tree system). Time, productivity and fuel consumption were recorded for both systems. A woodchip quality assessment of each assortment was performed in the laboratory according to European standards. The results obtained demonstrated that time consumption and productivity were similar between the integrated harvesting system and the whole tree system. Regarding the total energy balance, it should be noted that both systems produce woodchips that contain over ten times more energy than that required to mobilise and process the obtained biomass. Fuel consumption, costs and degree of damage were slightly higher in the whole tree system due to the more intensive forwarding operation. The two assortments of woodchips in the integrated system had a higher (chipped log material) and lower quality (chipped crown material) than whole tree woodchips. In conclusion, integrated harvesting is a better option to diminish fuel consumption, cost and environmental impact, and also to obtain better quality woodchips for the production of added value biofuels (pellets).

Keywords

Pinus halepensis, Selective Thinnings, Bioenergy Harvesting, Logging Residues, Woodchips, Net Energy Efficiency, Whole-tree Biomass

Introduction

There has been a substantial expansion of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) from plantations to abandoned agricultural land and natural sites dominated by shrubland across the Mediterranean basin, especially in the western area ([28]). After large public reforestation programmes conducted in Spain between 1950 and 1970, extensive areas were reforested in the Mediterranean regions with pine species, mainly with Pinus halepensis, with the goal of producing quality timber and restoring semi-arid and even arid deforested soils ([28]). Pinus halepensis is well adapted from semi-arid to sub humid conditions across the Mediterranean basin ([21]). Both forest growth and production ([41]) and natural regeneration ([18]) increase with the potential of the forest site, the bioclimatic stage, and soil fertility. Pinus halepensis forests is managed to produce even-aged stands including selective thinnings ([47]). Navarro et al. ([32]) showed a positive and significant response of Pinus halepensis trees in thinned stands compared to controls treatments, in spite of periods of low-rainfall and plague stress. These tree responses along with structural changes to afforestation affects forest management in the context of global change in the Mediterranean region where increases in temperature and reductions and irregularity in precipitation are forecasted, with the consequent rise in wildfire risks ([35]). Moreover, natural regeneration in Pinus halepensis stands is normally achieved by clear-cutting small areas in mature stands ([31]) in periods of 10 to 20 years or even after wildfires ([7]). Lavi et al. ([24]) showed that the natural dispersal of seeds is weak in Pinus halepensis stands. Consequently, spreading branches bearing cones from thinning or clearcutting increases the quantity of seeds dispersed. Furthermore, tillage associated with high cover density facilitates the establishment of seeds ([21]).

Regarding the state of forests in the Mediterranean basin, there is a general lack of forest management of Pinus halepensis stands, which has been confirmed in recent studies ([36], [16], [21]). Currently, less than 10% of the public forests have an active management plan in Eastern Spain ([26]). Moreover, the investment level in private forestry is very low due to the low economical revenues achieved by current forest projects. Therefore, in general, forest stands in large Mediterranean regions lack of any silvicultural treatments ([34]). High tree density, strong declining of the radial tree growth and continuous accumulation of dried biomass result in a low value and quite vulnerable stock with a high risk of wildfires ([36]).

Nevertheless, rising bioenergy markets in southern Europe offer an opportunity to mobilise untapped woody biomass helping to prevent and reduce wildfires in a context of climate change and energy transition ([6]). Woody biomass for bioenergy is the main source of renewable energy in Europe, with a share of almost 60%. The heating and cooling sector is the largest consumer, using about 75% of all bioenergy ([39]). Bioenergy contributes to EU’s energy security, as more than 95% of the demand is met with domestically produced biomass ([15]). Forestry is the main source of biomass for energy (logging residues, wood-processing residues, fuelwood, etc.) and wood pellets (mainly for heating) have become an important energy carrier ([39]). The forest-based biomass sector is well developed in central and northern Europe ([37]), featured by local and regional supply chains ([1]), conventional advanced forest operations ([43]) and logistics ([22], [45]) in forests and short rotation coppices ([40]). In contrast, southern Europe faces important challenges such as economic and regular restrictions, and a lack of adequate equipment and qualified personal for harvesting and processing, in both western ([16]) and eastern Mediterranean countries ([38]). Most forest development programmes in the Mediterranean basin aim at increasing the energy valorisation of residual forest biomass as a strategy to mobilise higher value-added wood products, prevent large wildfires and provide local employment in rural areas ([34]).

On the other hand, forest companies supplying roundwood primarily for sawmills and wood-based panel industries have limited experience in producing chips for bioenergy ([8]). Little research in biomass harvesting adapted to Mediterranean pine forest conditions has been performed and published, which has translated into a lack of knowledge by forest owners and harvesting companies about real market prices as well as harvesting and logistics costs ([26]). Therefore, there is a need for expanded knowledge of advanced harvesting technologies to produce woodchips in these increasingly growing forest areas ([34], [36], [16]).

The general objective of this study was to compare the integrated woody-biomass (IS) and whole tree harvesting (WTS) systems in representative forests of Pinus halepensis in pole stage for bioenergy uses. To achieve this, the research had the following specific objectives: (i) to analyse and compare time, biomass yield and fuel consumption; (ii) to calculate and compare productivity of both systems; (iii) to calculate and compare total harvesting costs; (iv) to assess the quality of the woodchips produced; and (v) to evaluate the net energy efficiency of each bioenergy system, from the forest to the bioenergy plant.

Materials and methods

Selection of representative plots

A representative 63-year-old afforested stand of Pinus halepensis established without any previous silvicultural treatment was selected in the forest district V074 Navalón, Spain (38° 55′ 10″ N, 00° 55′ 29″ W). Six plots of 0.25 ha (50 × 50 m) each were selected by random sampling from a homogeneous forest stand of 4 ha. The average terrain slope was 10%. Descriptive forest data is shown in Tab. 1.

Tab. 1 - Forest inventory data of the representative forest of the 60-years-old reforestation of Pinus halepensis. (SE): standard error of the mean.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Average DBH (cm) ± SE | 20.05 ± 1.86 |

| Basal area (G, m2 ha-1) | 24.94 |

| Density (trees ha-1) | 718 |

| Volume (m3 ha-1) | 106.5 |

| Average tree height (H0, m) ± SE |

14.2 ± 0.99 |

| Unit volume (m3 tree-1) | 0.14 |

In order to assure homogeneity among forest plots, the normality of the distribution of DBH and volume per tree were tested and subsequently, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied.

Harvesting methods

A low selective thinning was carried out with the same harvesting intensity (35% of the standing trees) over the six plots. After testing of the harvesting equipment by local forest contractors, the following harvesting systems were selected: (a) whole tree system (WTS), including full-tree chipping; (b) integrated harvesting system (IS) as traditional stem wood system (by delimbing tree stems) combined with the extraction of logging residues (tops and branches) in separated loads, also including separated chipping of stem and residues.

Each selected system had three test plots assigned. A single operator performed all felling operations using a 2.8kW chainsaw (model MS-261®, Stihl AG & Co., Waiblingen, Germany). Biomass (both stems and residues separately in the case of IS system) was forwarded by a single operator driving an 88 CV forwarder (model A83®, Valtra-Hitraf, Pontevedra, Spain); forest plots were located at a distance of 800 m from the forest road and with an altitudinal difference of 40 m between the forest plots and the loading area. Another operator comminuted the biomass collected with a semi-mobile chipper Stark SH-4585® (385 CV) connected to a truck; the biomass was separated into three different piles: woodchips from logs and woodchips from residues obtained from IS, and woodchips from whole-trees obtained from WTS (Fig. 1). The chipping process was carried out at the roadside three weeks later; this allow air drying the biomass to obtain chips with a lower moisture content and less fine material (especially needles and cones).

Fig. 1 - Woodchips from WST (left), woodchips from stem (middle) and crown material (right) from IS.

Finally, multi-lift trucks were loaded with the woodchips, which were transported to a bioenergy plant (40 km away) for final drying and transformation into thermal energy.

The same contractor performed the harvesting in all the plots (using the same machinery and operators) to avoid distortions on the field tests.

Time analysis

The time analysis followed the methodology developed by Magagnotti & Spinelli ([29]), corresponding to an observational study at plot level. The time of the working components (felling, extraction, chipping) in each plot was recorded manually with a stopwatch through a continuous-time measurement ([4]). In the felling phase, the time for felling, delimbing and cross-cutting of the crown was recorded, together with fuel recharging and chainsaw sharping time. The extraction phase was measured at a cycle level by recording the time consumed by the forwarder during loading, transport to the loading area, unloading and unloaded transport back to the plot. The chipping phase was measured at continuous time for each biomass pile. Mechanical, personal and organizational delay times were counted and registered. When no delays occurred, 35% of delay time over net time was assumed for gross calculations of forwarding times ([29]). Only one experimental plot was harvested at a time to ensure proper monitoring and recording of the time components. Furthermore, the same operators worked all plots to avoid variability due to experience and working conditions.

Analysis of biomass yield and fuel consumption

The number of felled trees per plot was counted while biomass volume and weight at 45% moisture content were estimated per plot and per hectare by measuring the height and DBH of each tree and applying the allometric equations for Pinus halepensis proposed by Montero et al. ([30]). During the felling phase, fuel and oil recharges (number and amount) were recorded. The forest contractor provided the fuel consumption data for the forwarder and chipper.

A t-test (α = 0.05) was applied to determine if the means of the two sets of data, in this case, biomass yield and fuel consumption, from WTS and IS were significantly different from each other.

Calculation of productivity

The productivity of each harvesting phase (felling, forwarding, and chipping; in t h-1) was calculated following the methodology described by Magagnotti & Spinelli ([29]) taking real productive machine hours from field time records. T-tests (α = 0.05) were applied to the productivity of each harvesting process to determine whether the means of the two datasets (WTS and IS) were statistically significantly different from each other.

Biomass quality assessment

Woodchip samples of 5 kg each one from the three different piles were separated and sent to the biomass laboratory of AIDIMME (Paterna, Spain). Here, the following equipment was used to analyse biomass quality: mechanical vibration equipment (model RO200N®, CISA Sieving Technologies, Barcelona, Spain); drying oven (UFE 700®, Memmert Gmbh, Schwabach, Germany); precision balance (ED1245®, Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany); muffle furnace (AAF1100®, Carbolite Gero Ltd., Hope, UK); 1kW particle mill (MF10®, IKA-Werke, Staufen, Germany); calorimetric pump (PARR 1351®, Parr Instruments Co., Moline, IL, USA).

The methodology proposed by the European standard EN-14961 ([12]) was followed for the analysis of woodchips quality. This standard details the procedures for the characterization of woodchips and thresholds to classify ranges of values to differentiate woodchip qualities. According to the standard, the features analysed were: classification of the material (described in [12] and [13]), humidity ([9]), ash content ([10]), and calorific value ([11]). Three repetitions were made for each woodchip fraction and test (woodchips from stems, from branches and from whole tree).

Calculation of harvesting costs

Machine rates were calculated based on conventional costing methods ([5]) using personnel and machine costs input from the harvesting company. Tab. 2shows the machine and labour cost inputs.

Tab. 2 - Machine and labour cost inputs for cost calculations. Cost in Euro (€) as on April 27, 2021 (1 € = 1.21 US). (SMH): scheduled machine hours, inclusive of delays; (*): incidence of work time over total work site time: the remaining time is represented by delays. The utilization rates, investment costs, overheads and industrial benefits were provided by forest operators (Moixent Forestal s.l., 2013).

| Costs | Unit | Chainsaw | Forwarder | Chipper | Truck |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment | € | 490 | 130000 | 240000 | 81000 |

| Service life | years | 6 | 10 | 12 | 15 |

| Resale | € | 98 | 26000 | 48000 | 16200 |

| Utilization* | SMH year-1 | 1000 | 1000 | 1500 | 1500 |

| Repairs | € | 41 | 5200 | 8000 | 1512 |

| Depreciation | € year-1 | 82 | 10400 | 16000 | 4320 |

| Average value of year investment | € year-1 | 286 | 83200 | 152000 | 50760 |

| Interests | % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Insurance | € year-1 | 2500 | 2500 | 2500 | 2500 |

| Interest | € year-1 | 14 | 4160 | 7600 | 2538 |

| Fuel | € year-1 | 1250 | 4431 | 30210 | 45315 |

| Lubricants | € year-1 | 375 | 1329 | 9063 | 13595 |

| Labour | € SMH-1 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Crew | n | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Overheads | € SMH-1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Total rate | € SMH-1 | 25 | 53 | 79 | 73 |

Calculation of the net energy efficiency of each bioenergy system

The final task of the study was to compare the net energy efficiency of the two bioenergy systems, including all the activities in the supply chain, from transport and logistics operations to the final thermal energy conversion of the woodchips at the bioenergy plant. To this purpose, Hohle ([20]) formulas were applied. This methodology allowed a quantitative comparison between the energy input required to carry out the forest operations and the obtained energy output through the transformation of biomass in a thermal combustion plant of 700 kWh per tonne of woodchips. Nevertheless, the energy consumed through the life cycle of machines, fossil fuel (extraction and refinery), and human work were not included in the calculations.

Results and discussion

Homogeneity of forest plots

According to ANOVA results, no significant differences were found between DBH and tree volume distribution among plots (p-value = 0.23 and p-value = 0.14, respectively) in both treatments.

Time consumption

Felling

Tab. 3shows the main results of felling time and productivity per harvesting system. WTS showed a lower average time consumption than IS (119 vs. 211 min plot-1), since the latter required an extra time for delimbing and crown cutting. Regarding fuel and oil recharge, this accounted for the same percentage (12%) in both systems, totaling 16.10 and 29.84 min plot-1 in the WTS and the IS systems, respectively.

Tab. 3 - Time consumption (min) of harvesting operations per plot and harvesting system. (SD): standard deviation; (CV): coefficient of variation. (*): assuming 35% of delays.

| Step | Operation | WTS | IS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plot1 | Plot2 | Plot3 | Mean | SD | CV(%) | Plot4 | Plot5 | Plot6 | Mean | SD | CV(%) | ||

| Felling | Felling | 133.83 | 137 | 85.5 | 118.78 | 28.86 | 24.29 | 217.8 | 188 | 226.16 | 210.65 | 20.05 | 9.52 |

| Fuel and oil recharge | 18 | 20 | 10.3 | 16.1 | 5.12 | 31.81 | 30.53 | 23.5 | 35.5 | 29.84 | 6.03 | 20.2 | |

| Total | 151.83 | 157 | 95.8 | 134.88 | 33.94 | 25.16 | 248.33 | 211.5 | 261.66 | 240.5 | 25.98 | 10.8 | |

| Time per tree | 1.53 | 1.67 | 1.15 | 1.45 | 0.27 | 18.4 | 2.12 | 2.38 | 3.08 | 2.53 | 0.5 | 19.6 | |

| Forwarding | n° cycles | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2.7 | 0.58 | 21.38 |

| Distance (m) | 800 | 700 | 700 | 733 | 57.74 | 7.88 | 850 | 750 | 750 | 783 | 57.74 | 7.37 | |

| Loading | 213.16 | 192.63 | 197.9 | 201.23 | 10.66 | 5.3 | 105 | 174.9 | 188.54 | 156.15 | 44.82 | 28.7 | |

| Transp. Loaded | 36 | 33.4 | 28.5 | 32.63 | 3.81 | 11.67 | 20 | 28.5 | 24.33 | 24.28 | 4.25 | 17.51 | |

| Unloading | 33.06 | 30.06 | 43.5 | 35.54 | 7.05 | 19.85 | 23 | 34.9 | 38.32 | 32.07 | 8.04 | 25.08 | |

| Transp. Unloaded | 27.77 | 27.32 | 19 | 24.7 | 4.94 | 19.99 | 17 | 19.5 | 17.32 | 17.94 | 1.36 | 7.58 | |

| Net | 309.99 | 283.41 | 288.9 | 294.1 | 14.03 | 4.77 | 165 | 257.8 | 268.51 | 230.44 | 56.92 | 24.7 | |

| Gross* | 418.49 | 382.6 | 390.02 | 397.04 | 18.95 | 4.77 | 222.75 | 348.03 | 362.49 | 311.09 | 76.85 | 24.7 | |

| Chipping | - | 20.5 | 20.6 | 19 | 20.03 | 0.9 | 4.47 | 21.3 | 24.9 | 19.5 | 21.9 | 2.75 | 12.56 |

Forwarding

Tab. 3shows the time consumption per plot and harvesting system for the forwarding operation. Total average loading time was 156 min plot-1 for IS and 201 min plot-1 for WTS. The number of forwarding cycles from the stump to the loading area was greater for WTS, with an average of 4 cycles plot-1 vs. 3 cycles plot-1 in the case of IS in which residues and stems were forwarded separately. The results revealed that the net payload of the forwarder was reduced by the bigger volume occupied by the whole trees. Tolosana et al. ([44]) reported similar results with a Timberjack 1410 and a Dingo forwarder, demonstrating that tree volume is the critical factor when forwarding whole trees.

The average time of transport loaded was quite similar, i.e., 33 min for the WTS and 24 min for the IS. This differences could be explained by a speed reduction of 5.36%, with 90 m min-1 in the case of WTS and 85 m min-1 in the case of IS, which transported bigger loads per cycle. Unloading time was very similar, with an average of 36 min and 32 min for WTS and IS, respectively. Finally, there was a non-significant difference in the total time per plot associated with transport unloaded. Despite the similar speed, this occurred because WTS required more transport cycles per plot than the IS system.

Chipping

Tab. 3shows the results for chipping operations. On average, the chipping of the biomass took 20 min for the WTS and 22 min for the two piles obtained with IS system.

Biomass yield and fuel consumption

Tab. 4shows the biomass yield of the two analysed systems. The average value of green biomass yield for WTS (23.76 t ha-1) was slightly lower than for IS (26.66 t ha-1). The quantity of extracted biomass was not the same due to slight differences in diameter and height of the felled trees. Nevertheless, the t-test analysis showed no significant differences (p-value = 0.21). This confirmed that the same thinning intensity was implemented in all forest plots and harvesting system, allowing an accurate comparison of the variables analysed in this study.

Tab. 4 - Comparisons of biomass yield per forest plot and harvesting system. (SD): standard deviation; (CV): coefficient of variation.

| System | Test plot | Biomass yield (green t ha-1) |

|---|---|---|

| WTS | Plot1 | 24.27 |

| Plot2 | 24.46 | |

| Plot3 | 22.56 | |

| Mean | 23.76 | |

| SD | 1.05 | |

| CV(%) | 4.40 | |

| IS | Plot4 | 29.04 |

| Plot5 | 23.50 | |

| Plot6 | 27.44 | |

| Mean | 26.66 | |

| SD | 2.85 | |

| CV(%) | 10.69 |

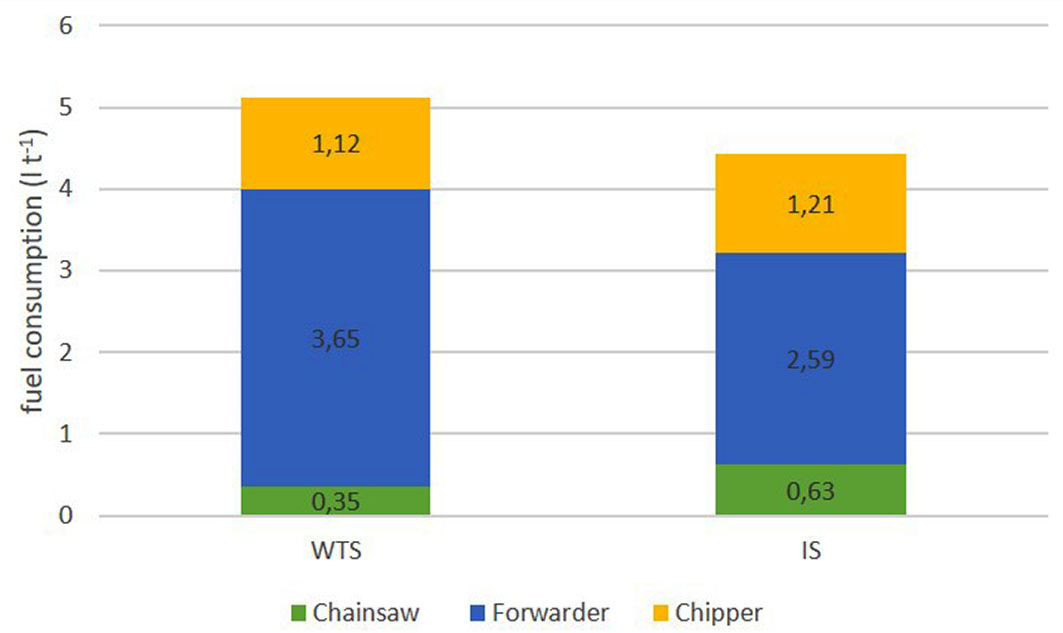

Fig. 2shows the fuel consumption of the two harvesting systems. On average, fuel was recharged 8.4 times in IS, with an average total consumption of 2.12 litres per plot, and 4.3 times in WTS, with an average total consumption of 2.7 litres per plot. Therefore, the average fuel consumption of the chainsaw operation per tonne in IS (0.63 l t-1) almost duplicated that of WTS (0.35 l t-1), being the difference statistically significant (p-value = 0.04). This can be explained by the further processing time involved in IS with delimbing. As for the forwarder, the obtained fuel consumption of the two systems (2.59 and 3.65 l t-1 for IS and WTS, respectively) was not significantly different (p-value = 0.13). Also, the fuel consumption of the chipper was similar in both systems (1.21 l t-1 for IS and 1.12 l t-1 for WTS) and no significant differences were found (p-value = 0.32). As for total fuel consumption, WTS consumed 5.12 l t-1 in contrast to 4.43 l t-1 of IS. These results confirmed that chainsaw fuel consumption is the factor underlying the significant differences in fuel consumption between harvesting systems.

Productivity

Tab. 5shows a summary of the productivities by plot and operation for the two harvesting systems under study.

Tab. 5 - Comparisons of productivity and costs of the two harvesting systems. (P): productivity; (Av. P): average productivity; (Hc): hourly cost; (EWT): effective working time; (Uc): unit cost; (SD): standard deviation; (CV): coefficient of variation; (*): as result of fixed and variable cost plus industrial profit and overheads (calculated as 6% and 8% of hourly operating costs, respectively, according to forest operators).

| System | Operation | Plot/ Stats |

P (t h-1) |

Av. P (t h-1) |

Hc (€ h-1)* |

EWT (h t-1) |

Uc (€ t-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTS | Felling | Plot1 | 2.4 | 2.76 | 25 | 0.36 | 9.06 |

| Plot2 | 2.34 | ||||||

| Plot3 | 3.53 | ||||||

| SD | 0.67 | - | - | - | - | ||

| CV(%) | 24.44 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Forwarding | Plot1 | 1.17 | 1.21 | 53 | 0.83 | 43.73 | |

| Plot2 | 1.29 | ||||||

| Plot3 | 1.17 | ||||||

| SD | 0.07 | - | - | - | - | ||

| CV(%) | 5.79 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Chipping | - | 17.79 | 17.79 | 79 | 0.06 | 4.44 | |

| Transport | - | 22 | 22 | 73 | 0.05 | 3.32 | |

| Total | - | - | - | - | - | 60.56 | |

| IS | Felling | Plot4 | 1.75 | 1.66 | 25 | 0.6 | 14.98 |

| Plot5 | 1.67 | ||||||

| Plot6 | 1.57 | ||||||

| SD | 0.07 | - | - | - | - | ||

| CV(%) | 5.79 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Forwarding | Plot4 | 2.64 | 1.85 | 53 | 0.54 | 28.87 | |

| Plot5 | 1.37 | ||||||

| Plot6 | 1.53 | ||||||

| SD | 0.67 | - | - | - | - | ||

| CV(%) | 37.47 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Chipping | - | 16.55 | 16.55 | 79 | 0.06 | 4.77 | |

| Transport | - | 22 | 22 | 73 | 0.05 | 3.33 | |

| Total | - | - | - | - | - | 51.93 |

Felling

The average felling productivity of WTS exceeded that of IS (2.76vs. 1.66 t h-1, respectively; t-test p-value = 0.04) as the latter required additional wood processing (delimbing) time. Furthermore, the felling productivity obtained for IS (2.5 m3 h-1 for a green density of 0.668 t m3 at 35% moisture content) was similar to that obtained by Ambrosio ([3]), who reported a felling productivity of 2.7 m3 h-1 for a manual selective thinning on a similar stand of Pinus sylvestris in northern Spain. Spinelli et al. ([42]) also found significant differences between the WT and CTL harvesting systems.

Forwarding

On average of 4 trips and 294 min were required by the forwarder to move for forwarding 5.94 tonnes of biomass in WTS, whereas 2.7 trips and 230 min were required by the forwarder to move 6.66 tonnes in IS. Therefore, the productivity of the forwarding operation in IS was 52% higher than in WTS (1.85 vs. 1.21 t h-1). Nevertheless, we found no significant difference between treatments after t-test (p = 0.18). The higher forwarding productivity of IS was previously highlighted by Heikkilä et al. ([19]), who reported a higher productivity when forwarding delimbed logs and stems (10-20% higher) than forwarding whole trees. This is mainly due to the bigger apparent volume occupied by the branches in whole trees loads compared with separated loads of logs and logging residues.

The low productivity rates calculated in our study differed from those reported by Tolosana et al. ([44]), who obtained 10.2 t h-1 for the Timberjack and 3.2 t h-1 for the Dingo in IS. In their study, the forwarders worked systematically extracting logs to forest tracks and aligning forest residues from crowns and branches. In our research the forwarder moved selectively from one tree to another. A systematic alignment resulted in a substantial increase in the forwarding productivity of IS. Additionally, Nurmi & Hillebrand ([33]) reported that forwarder capacity, distance to loading area, weight and quantity of biomass per hectare are key factors for the productivity in the forwarding operation. Based on our experience, felling and forwarding productivities increase with larger harvested areas and higher biomass yields per hectare.

Chipping

Regarding chipping productivity, the forest company only provided the total time spent by the chipping operation in each system. From this data, the calculated net productivity was 17.79 t h-1 for WTS and 16.55 t h-1 for IS. This is mainly due to the fact that in the case of IS, the chipper does not have to move from one pile (woodchips from stems) to another (woodchips from forest residues) during the chipping operation. Tolosana et al. ([44]) obtained a similar productivity (14 t h-1) in a chipping operation on residues of Pinus sylvestris (branches and tops piled up in the landing area).

Biomass quality

In our study, biomass quality highly depended on the fraction of the three piles obtained and analysed after the chipping operation (Fig. 1). Tab. 6shows the results obtained in the laboratory for particle size, moisture, ash content and net calorific value, as well as their assigned quality classes following standard EN-14961 ([12]).

Tab. 6 - Comparisons of biomass quality of woodchips obtained from the two harvesting systems. (o.d.): oven-dried.

| Characteristics | WTS | IS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin of chips sample | Whole tree | Stem | Branches |

| Particle size (mm, [13]) | P31.5 | P31.5 | P31.5 |

| Moisture content (% o.d. weight, [9]) | 41 | 45.18 | 38.13 |

| Ash content (% o.d. weight, [10]) | 2 | 1.09 | 3.24 |

| Net calorific value (MJ kg-1, [11]) | 17.53 | 17.59 | 17.27 |

| Quality ([12]) | ENPLUS B1 | ENPLUS A2 | - |

The woodchips obtained from WTS were rated as EN PLUS B1, while IS supplied two different qualities: EN PLUS A2 for log chips (if dried up to 35% moisture content). The rest of woodchips from logging residues did not pass the EN quality tests due to the high content of ashes. These results are in line with those reported by Spinelli et al. ([42]) who indicated that WT harvesting produces whole-tree chips which contain a larger proportion of needles and twigs compared to the chips obtained from CTL harvesting. Nevertheless, they are suitable for use in small-scale residential heating systems.

Regional market prices for the different woodchip quality assortments determine the convenience of one system over the other. Generally, obtaining two qualities of woodchips as in IS might result in higher revenues and this would justify the processing (delimbing) of the logs and the separate piling and chipping performed in IS.

Costs

Tab. 5shows the cost summary for the two harvesting systems. Assuming a transport with a multi-lift truck from the forest landing area to a bioenergy plant located 40 km away, the unit cost for WTS (60.56 € t-1 at 45% biomass moisture content, hereafter: MC) was slightly higher than for IS (51.93 € t-1 at 45% biomass MC). These costs amounted to 110.10 € t-1 for the WTS and 94.42 € t-1 for the IS at 0% of biomass MC. Using the wood calorific values calculated for Pinus halepensis, average costs per energy unit bases were 22.61 and 19.39 € MWh-1 for WTS and IS, respectively.

These results are in line with those reported by ENERSILVA ([14]) for several Mediterranean pine species (41-95 € t-1 at 26% MC). For the same MC our results were 95 € t-1 for WTS and 65 € t-1 for IS. In contrast, the cost obtained were clearly higher than those presented in a previous study by Frühwald ([17]) where the cost of woodchips from biomass residues were lower than the costs from whole tree harvesting for Picea abies in Scandinavia and Northern Germany (10 € MWh-1 and 15 € MWh-1, respectively). The net calorific value of the biomass from Mediterranean pinewood was slightly higher than that of softwoods from Central and Northern Europe ([27]). However, selective thinnings oriented to fire prevention in stands with low stocking volume and significant terrain slopes cannot compete from a pure economic point of view with selective thinnings of spruce or Scots pine forests on flat lands in Central and Northern Europe. Thus, both the productivity and cost of the wood and harvesting system are determined by forest stand and harvesting variables such as tree sizes, harvesting intensity, forwarding distance, and operators qualities ([25]). Tab. 5shows that the most expensive operations were forwarding followed by manual chainsaw felling. The lower productivity of the forwarding operation in WTS was compensated by the higher felling productivity. According to Kellogg & Spong ([23]), forwarding was the most expensive activity in both systems, which accounted for 72% and 57% of the total costs in WTS and IS, respectively. These results are consistent with those presented by Adebayo et al. ([2]) who reported that 54% and 36% of the costs were attributed to the forwarding operation in WTS and IS, respectively, with the difference that in this study the felling was mechanized. Differences in total costs between WTS and IS keep constant of 20% for both the above studies ([23], [2]). It must be considered that with bigger forwarders these costs could be reduced, although potential environmental impact (damages to soil and remaining vegetation) might occur. Additional systematic operations like piling of forest residues and alignment of logs or whole trees along forest tracks could increase forwarding productivities and reduce costs. Moreover, it has to be considered that costs may vary considerably from company to company, and experimental trials are normally more cost-intensive than real working operations.

Net energy efficiency

We conducted a comparative analysis of the net energy efficiency along the entire supply chain, from the forest to the thermal energy conversion of the obtained woodchips. The analysis included all fossil fuels consumed by the harvesting, chipping and transport equipment. The input to output energy rate was 9.3% for the WTS and 8.3% for the IS. A total of 10.7 and 12.0 of units of equivalent biomass energy were produced from every unit of energy input of fossil fuel required to mobilise and transform the biomass for WTS and IS, respectively. These results agree with those reported in the ForBioEnergy ([16]) project, which included several pine studies in Spain, Italy, Slovenia and Croatia. The lower value of bioenergy units produced in WTS was due to the higher energy consumption of the forwarding operation. This highlights that is critical to optimize such process to increase the net energy efficiency of the supply chain ([49]). Results were determined by the size and capacity of the reference combustion plant and were in line with Wihersaari ([48]) who obtained 30 to 50 units of bioenergy produced for every unit of (fossil) energy consumed from fuel chips from logging residues at final harvest. In another study, Valente et al. ([46]) reported that WTS can produce 20 units of bioenergy per fossil fuel energy unit. The higher values reported by the mentioned studies show a potential improvement in energy efficiency that probably could be achieved by including larger harvesting areas and optimizing the logistics operations.

Conclusions

Biomass yield and fuel consumption were similar between WTS and IS harvesting system, while time differences are due to the higher processing time that IS requires during the felling operation, and to the lower forwarding capacity per cycle in WTS caused by the higher apparent volume of whole trees in comparison with the separate forwarding of stems and residues in IS.

The felling productivity of WTS was higher than that of IS. Nevertheless, the forwarding productivity of WTS was lower than that of IS. No significant differences were found for the biomass chipping from both systems. Both harvesting systems yielded woodchip of quality complying with non-industrial EN standards. Total harvesting costs were slightly higher in WTS due to the more intensive forwarding operations.

Both harvesting systems produce woodchips whose energy is tenfold higher than that required to mobilise and process the harvested biomass. This implies a high potential for the substitution of non-renewable fossil fuels by wood-based biofuels. Nevertheless, further investigations including life-cycle analyses of biofuels is needed to confirm this issue.

After the evaluation of the productivity, fuel consumption, and energy efficiency of WTS and IS, we conclude that IS is the most productive, economic and environmental effective harvesting system for the harvesting of pole stage stands of afforested Pinus halepensis. Nevertheless, both systems are highly sensitive to machine productivity and forest stand variables.

Acknowledgements

VLA and JVOV conceived the study and draft the manuscript; VLA carried out the field measurements; VLA and GSO carried out the biomass tests in the laboratory; VLA, JVOV and JFUS performed the statistical analysis.

This work was partially funded by the Government of Valencia (IVACE, Spain) in the framework of the BIOPELLET project. The authors want to acknowledge the support of the forest company Moixent Forestal, the Municipality of Enguera and the AIDIMME Technology Institute and very especially the support of Dr. Raffaele Spinelli for providing methodological support in the frame of COST Action FP0902. Finally, a special thank to the reviewers who improved and enriched the publication with their valuable contributions.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Jose-Vicente Oliver-Villanueva 0000-0003-2842-7834

Javier F Urchueguia-Schölzel 0000-0002-3054-3431

Universitat Politècnica de València, Institute for Information and Communication Technologies - ITACA, Research Group on ICT vs. Climate Change, Camí de Vera s/n, 46022 València (Spain)

AIDIMME - Wood&Metal Technology Institute, Benjamin Franklin 13, 46180 Paterna (Spain)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Lerma-Arce V, Oliver-Villanueva J-V, Segura-Orenga G, Urchueguia-Schölzel JF (2021). Comparison of alternative harvesting systems for selective thinning in a Mediterranean pine afforestation (Pinus halepensis Mill.) for bioenergy use. iForest 14: 465-472. - doi: 10.3832/ifor3636-014

Academic Editor

Rodolfo Picchio

Paper history

Received: Aug 27, 2020

Accepted: Aug 10, 2021

First online: Oct 16, 2021

Publication Date: Oct 31, 2021

Publication Time: 2.23 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2021

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 33038

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 27939

Abstract Page Views: 2431

PDF Downloads: 2084

Citation/Reference Downloads: 4

XML Downloads: 580

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 1584

Overall contacts: 33038

Avg. contacts per week: 146.00

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2021): 9

Average cites per year: 1.80

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Deploying an early-stage Cyber-Physical System for the implementation of Forestry 4.0 in a New Zealand timber harvesting context

vol. 17, pp. 353-359 (online: 13 November 2024)

Research Articles

Modeling of time consumption for selective and situational precommercial thinning in mountain beech forest stands

vol. 14, pp. 137-143 (online: 16 March 2021)

Research Articles

The physicomechanical and thermal properties of Algerian Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) wood as a component of sandwich panels

vol. 15, pp. 106-111 (online: 21 March 2022)

Research Articles

Modifying harvesting time as a tool to reduce nutrient export by timber extraction: a case study in planted teak (Tectona grandis L.f.) forests in Costa Rica

vol. 9, pp. 729-735 (online: 03 June 2016)

Research Articles

Changes in moisture exclusion efficiency and crystallinity of thermally modified wood with aging

vol. 12, pp. 92-97 (online: 24 January 2019)

Research Articles

Energy production of poplar clones and their energy use efficiency

vol. 7, pp. 150-155 (online: 23 January 2014)

Research Articles

Nutritional, carbon and energy evaluation of Eucalyptus nitens short rotation bioenergy plantations in northwestern Spain

vol. 9, pp. 303-310 (online: 05 October 2015)

Research Articles

Logging residue chipping options for short rotation poplar plantations

vol. 16, pp. 23-29 (online: 15 January 2023)

Research Articles

Investigating the effect of selective logging on tree biodiversity and structure of the tropical forests of Papua New Guinea

vol. 9, pp. 475-482 (online: 25 January 2016)

Research Articles

Can traditional selective logging secure tree regeneration in cloud forest?

vol. 10, pp. 369-375 (online: 07 March 2017)

iForest Database Search

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords