The physicomechanical and thermal properties of Algerian Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) wood as a component of sandwich panels

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 15, Issue 2, Pages 106-111 (2022)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor3952-015

Published: Mar 21, 2022 - Copyright © 2022 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) is the main forest species of Algeria occupying more than 35% of the total forest area of the country. However, the physicomechanical and thermal characteristics of Algerian P. halepensis wood are not well-known. This research investigates the physical (moisture, density, swelling, and shrinkage), mechanical (bending strength and modulus of elasticity), and thermal (mass loss under combustion and pyrolysis as well as thermal conductivity) properties of P. halepensis wood from the Darguina (Bejaia) forest in Algeria. The results showed that Algerian P. halepensis wood with a mean density of 540 kg m-3 has good dimensional stability in swelling and shrinkage, with 116.43 MPa bending strength and a modulus of elasticity of 17,520 MPa. The wood shows a good thermal resistance under low-temperature range and has a thermal conductivity of 0.21 W m-1 K-1. The overall results indicate that Algerian P. halepensis wood may be commercially exploited for construction and insulation applications, namely in the production of sandwich composites.

Keywords

Density, Bending Strength, Thermal Conductivity, Shrinkage, Swell-ing

Introduction

Wood is a natural cellular material characterized by heterogeneous structural features, porosity and high hygroscopicity. The mechanical behavior of wood depends on its specific anatomical structure, density and moisture content as well as on tree related variables such as age and growth characteristics ([40], [35]). The properties of wood are species specific and a careful characterization is therefore necessary prior to application of wood.

The Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) belongs to the Pineaceae family and is a species that quickly colonizes abandoned lands ([16], [29]). It is a pyrophyte species naturally distributed throughout the Mediterranean basin, including North Africa, Spain, France, and Italy ([27]). More than 2.5 million hectares of P. halepensis are located in semi-arid and arid regions ([28]), at low altitudes and along the coast ([30]). P. halepensis is considered as the most important and dominant forest tree species in Algeria, covering an estimated area of 1,158,533 ha ([8]) growing in all bioclimatic zones, with a predominance in the semi-arid zone, from East to West, and from sea level to the major mountain ranges ([34]). Its detailed distribution in Algeria is as follows: in the Eastern region: in the forests of the Tébessa and Aures mountains; in the Central region: in the forests of Ouarsenis; in the Western region: in the wooded mountains of Saida, Mascara, Sidi Bel Abbes; and the Atlas Sahara: in the forests of the Ouled Nail mountains, near Djelfa and Djebel Amour, near Aflou ([32]).

The easy adaptation of P. halepensis to various eco-climatic conditions and poor soils makes the species a desired tree for reforestation programs in Mediterranean countries ([12], [27], [31], [36]). Silvicultural treatments of the species have been investigated in different countries ([31]) for forest management. The chemical properties of P. halepensis wood showed that it is a rich source of resin acids and cyclic polyols ([8]). Its physicomechanical properties are similar to those of maritime pine wood (Pinus pinaster - [39]). Therefore, a replacement of maritime pinewood with P. halepensis wood may be considered for the production of construction timber, plywood, and particle board, particularly for North African countries.

In recent years, P. halepensis wood has been studied as face (skin) layers for the production of cork sandwich composites because it is a renewable and widely available material in Algeria ([23], [24], [26]). The sandwich composites or sandwich panels are interesting materials for construction because they have high strength-to-weight ratio, high flexural stiffness, and low weight ([17]); therefore, they find a variety of applications in construction. The material properties of sandwich panels including dimensional stability, thermal conductivity, and mechanical strength depend on the properties of face and core layers ([17]). The current research on the wood characteristics of P. halepensis wood is still scarce namely regarding the wood physicomechanical and thermal characteristics of the species in Algeria.

The aim of this study is to fill this gap and for the first time determine the physical and mechanical as well as the thermal properties of Algerian P. halepensis wood to lay the groundwork for development of future applications and further research, particularly on cork-based sandwich composites.

Material and methods

Materials

The P. halepensis wood samples were obtained from the region of Darguina (Bejaia, Algeria) by felling two 70-year-old trees with straight stems having an acceptable sanitary state and over 40 cm diameter at 1.50 m above the ground. The Darguina region has an annual temperature of 16.2 °C, an annual precipitation of 771 mm, and a climate type of “Csa” according to Köppen and Geiger classification. Sawing of the wood, sample preparation and physicomechanical tests were performed at the Research Unit of Processes, Material and Environment (URMPE) of the University of Boumerdès (north Algeria). The sampling methods adopted in this work comply with French and international standards ([2] and [19], respectively).

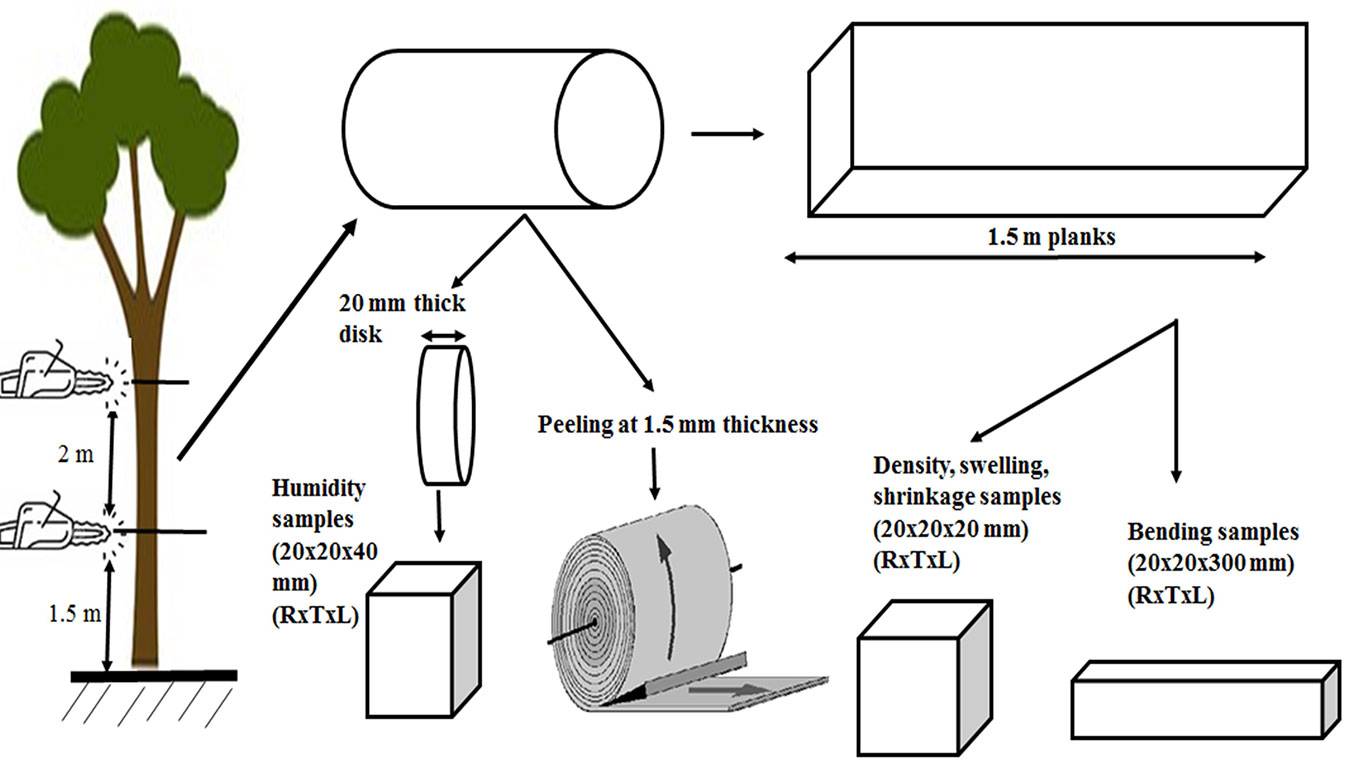

The tree stems were cut into logs and conditioned at ambient air conditions during a week to remove part of its natural moisture. The logs were then cut with a chain saw into two longitudinal planks, which were planned to obtain smooth surfaces and peeled into 1.5 × 0.5 m2 veneer sheets for the determination of thermal conductivity (Fig. 1). The P. halepensis solid wood samples used for the physicomechanical characterizations did not differentiate the sapwood and the heartwood.

Fig. 1 - Preparation of specimens for physical and mechanical characterization (directions: R, radial; T, tangential; and L, longitudinal).

Fig. 1represents an overview of the sampling procedure adopted for the physical and mechanical tests on the wood of P. halepensis. A total of 20 solid wood specimens were produced with radial × tangential × longitudinal dimensions of approximately 20 × 20 × 300 mm for mechanical tests. The physical and mechanical properties, namely density, moisture content, dynamic elastic modulus, as well as thermal degradation and thermal conductivity were determined according to the respective standards, as explained in the following sections. The wood samples were conditioned under 65% relative humidity and 20 °C temperature to obtain approximately 12% moisture content in wood samples before the physicomechanical and thermal tests.

Physical characterization

Moisture mapping

The water content of the wood was determined as the proportion of free and bound water relative to the dry weight of sample by the standard B51-004 ([3]). A 20 mm wide wood stem cross-section was cut from the P. halepensis logs and immediately cut into 45 small prisms of 20 × 20 × 40 mm, covering the whole cross-section and numerated according to the location of each sample in the disk. Each prism was weighed using a balance with a 1 mg accuracy (moist-weight), dried in a stove at 103 ± 2 °C until equilibrium and weighed again.

The cross-sectional mapping of moisture in the P. halepensis stem was established using a Visual Basic™ computer program based on the reconstitution of the moisture content after calculating the moisture content of the prisms based on their position, followed by estimating the moisture content for each point on the disk using the form function ([13]).

Determination of density

For the determination of density, a total of 12 P. halepensis wood specimens with dimensions 20 × 20 × 20 mm were weighed and their dimensions measured with a digital caliper, as specified by the French standard B51-005 ([4]).

Determination of swelling

A total of 12 specimens (20 × 20 × 20 mm) were placed in water during 12 days. During this period, the specimens were removed from the water, wiped and daily weighed until constant weight was reached, corresponding to maximum moisture content. The swelling of wood in different directions were calculated from swellings of the wood between the dry state and above the fiber saturation point (FSP).

The volumetric swelling of wood was expressed by the sum of radial, tangential, and longitudinal swelling values ([18]).

Determination of shrinkage

A total of 12 specimens (20 × 20 × 20 mm) above fiber saturation moisture content were placed in an oven at 103 °C. The weight and dimensional changes of the specimens were monitored daily, according to B51-006 ([5]) standard. The measurement of the dimensions was made with a digital caliper (accuracy: 0.01 mm).

The anisotropy of shrinkage (A) is expressed by the ratio of tangential shrinkage to radial shrinkage. It gives an indication of the distortions that may occur in wood during drying below the fiber saturation point. The volumetric shrinkage (RV) is defined as the relative change in volume between the saturated state and the dry state ([15]).

Mechanical characterization

Bending strength and modulus of elasticity

The 3-point bending test ([6]) was carried out using a Zwick universal machine provided with a force sensor using a 10 kN load at a speed of 2 mm min-1. A total of 20 samples with 20 × 20 × 300 mm dimensions were used in the bending test. The machine was computer controlled and the software testXpert® v. 12.0 (ZwickRoell, Genoa, Italy) was used for data acquisition.

For the determination of bending strength (modulus of rupture, MOR), the following equation was used based on DIN-52186 standard ([10], [37] - eqn. 1):

where b is width, h is thickness, l is the distance between the centers of the supports, and F is the maximum force applied. The bending modulus of elasticity is the ratio of stress to corresponding strain within the elastic region and was calculated based on EN-310 ([14]) standard using the following formula (eqn. 2):

In this equation the elastic range was calculated between 10% and 40% of the maximum force. ΔF shows the variation in the force (N) and Δf shows the variation in the deflection (mm - [37]).

Thermal properties

Low-temperature thermal degradation

The thermal behavior of the P. halepensis wood was analyzed with particle (approximately 5 mm) and powder (<250 μm) wood samples at temperatures between 25 and 250 °C using a thermogravimetric analyzer. A four step heating program was used under air and Argon gas flow conditions: heating from 25 to 100 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min-1, an isothermal step at 100 °C for 30 min, heating from 100 to 250 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min-1, and finally an isothermal step at 250 °C for 5h. Air or Argon gas flow rates were set to 60 ml min-1.

Thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity of the materials used was measured using a thermal conductivity analyzer (TC-Meter). In the measurement, through a combination of a heating element and a temperature sensor, the temperature increase in the wood sample was measured during a pre-defined heating power and heating period in a transient state. The sensor wire is placed between the two test samples of the same material. This probe is disposed in a kapton membrane connected in series with a voltmeter and a current generator that measures, through the Joule’s law, the heat emitted at the surface of the test material.

The thermal conductivity analyses were performed on P. halepensis wood veneer samples in the longest and smallest directions by triplicate measurements. The test samples (15 × 15 × 2 cm) have been obtained from veneers of 1.5 × 0.5 m2 dimensions and a thickness of 1.5 mm. The ISO-8894-1 ([20]) standard was followed in the measurement of thermal conductivity.

Results and discussion

Moisture mapping and density

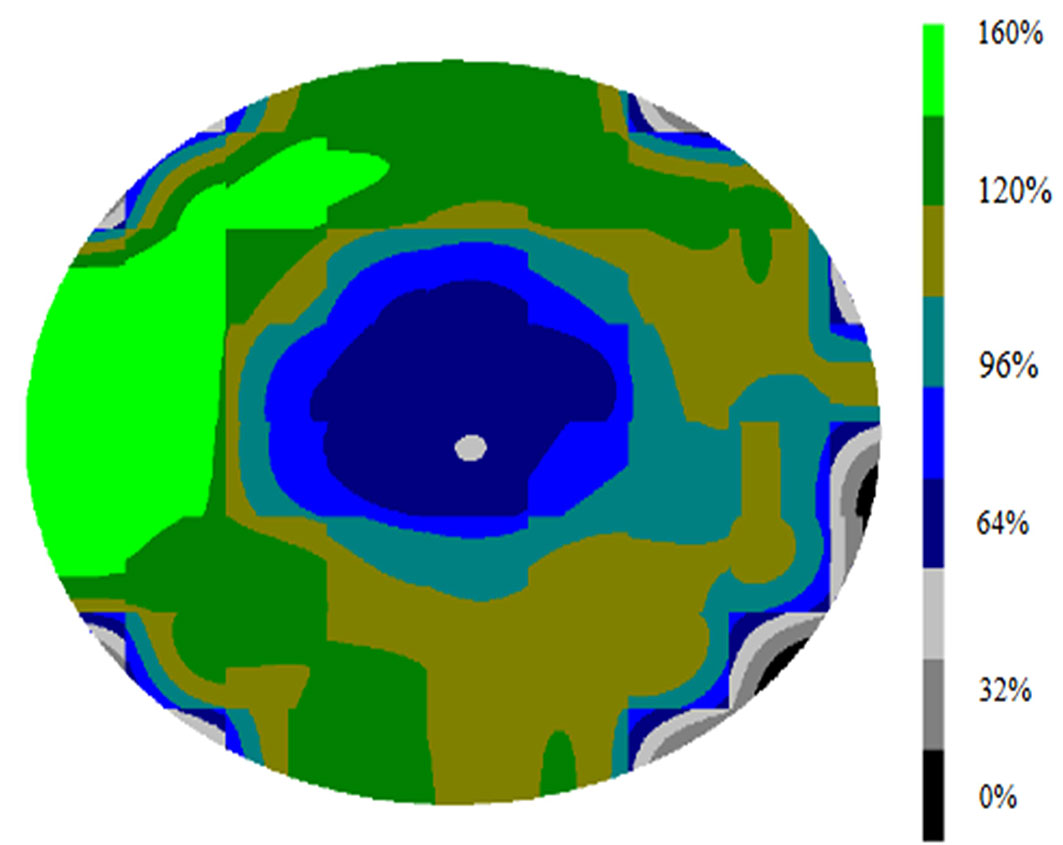

The average moisture was 96% in the green wood, in agreement with the generally found moisture content in recently felled trees ([40]). The moisture mapping shows that the water content distribution was not homogeneous along the cross-section while being more variable in the sapwood and more uniform in the heartwood (Fig. 2). Moisture content increases gradually from the center of the log to outside in accordance with the previous observations in softwoods ([40]).

Fig. 2 - Mapping of moisture on a cross-section of P. halepensis wood. Moisture content increases from black-grey to green colours corresponding to drier and moist regions, respectively. Adapted from Lakreb ([22]).

The water content was maximal in the area of the sapwood (moisture content between 60% and 160%) while the less moist heartwood contained moisture levels between 30% and 60%. These findings are in accordance with those reported in the literature (moisture contents of 30-40% and 60-100% for heartwood and sapwood, respectively - [9]).

Tab. 1summarizes the range, mean and standard deviation of density of Algerian P. halepensis wood, as well as the values from a comparative study with P. halepensis wood from different Mediterranean countries. The mean density of Algerian P. halepensis wood was 540 kg m-3 which is within the range reported. For instance, Nahal ([32]) reported a density (without specifying the moisture content) between 532 and 866 kg m-3, while Erten & Sözen ([15]) found an air-dry density of Turkish P. halepensis wood between 540 and 614 kg m-3. Similarly, Langbour et al. ([25]) reported the density of French P. halepensis wood between 530 and 580 kg m-3. Another similar density value (580 kg m-3) was reported by Limam et al. ([26]). These values suggest that the reported density values may vary as high as 60% for P. halepensis wood. This variation occurs possibly due to the differences in measuring density (oven-dry basis or air-dry basis) and differences in moisture content and chemical composition between the tested P. halepensis woods ([40]).

Tab. 1 - Density of Algerian P. halepensis wood and comparison with other P. halepensis woods from the Mediterranean area.

| Provenances | References | Density range (kg m-3) |

Average density (kg m-3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | This work | 500-580 | 540 |

| Algeria, Lebanon, France | Nahal ([32]) | 532-866 | 724 |

| Tunisia | Quiquandon ([33]) | - | 560 |

| France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Tunisia, Morocco, Israel | Thibaut et al. ([39]) | - | 570 |

| Turkey | Erten & Sözen ([15]) | 540-610 | 575 |

| France | Langbour et al. ([25]) | 450-580 | 515 |

| Algeria | Limam et al. ([26]) | - | 580 |

| Tunisia, Italy, Spain, Israel | Elaieb et al. ([12]) | 520-620 | 570 |

Swelling properties

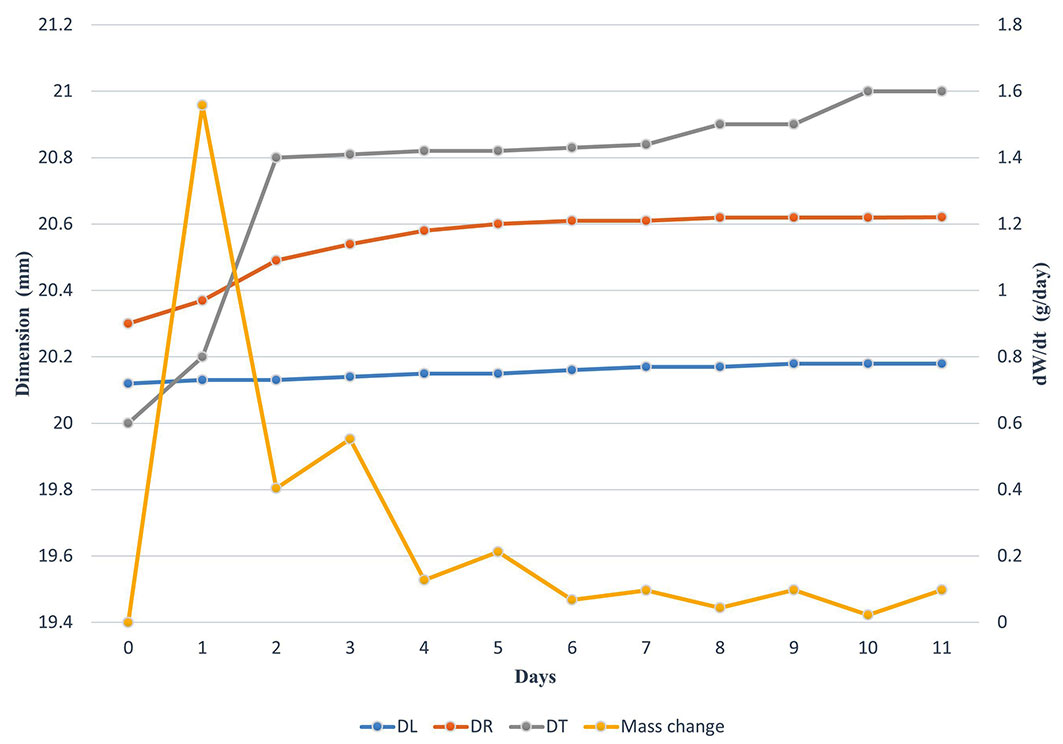

The variation in wood dimensions (in longitudinal, radial, and tangential directions) and wood mass during water immersion of the P. halepensis wood is shown in Fig. 3. The mass increase due to water absorption was significant in the first 24 h, then decreased sharply and attained a rather stable condition after 5 days.

Fig. 3 - Mass and dimensional changes in the three main directions: longitudinal (L), radial (R), and transverse (T) of P. halepensis wood along time during water immersion.

The wood dimensional variation along time shows that most of the swelling occurred in the first two days of immersion. Also, a clear anisotropy in swelling was observed with a very small swelling in the longitudinal direction (0.3% after 11 days of immersion) and the highest value for the tangential direction (5.0% and 1.6% for the tangential and radial swelling respectively). The volumetric swelling was 6.9% (Tab. 2).

Tab. 2 - Mean swelling (α), shrinkage (R), volumetric swelling and shrinkage (V), and Anisotropy (A) of P. halepensis wood in the three directions (L, R and T). (STD): standard deviation.

| Values | Variable | Parameter | Mean ± STD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental values | L (%) | α | 0.29 ± 0.11 |

| R | 1.14 ± 0.31 | ||

| R (%) | α | 1.58 ± 0.53 | |

| R | 3.76 ± 1.04 | ||

| T (%) | α | 5.00 ± 1.56 | |

| R | 4.76 ± 1.34 | ||

| Calculated values | V (%) | α | 6.87 |

| R | 8.34 | ||

| A (%) | - | 1.26 |

The results indicate that the swelling of Algerian P. halepensis wood is smaller than that of Turkish P. halepensis wood (7.2-9.4% and 5.0-5.7% for tangential and radial swelling values, respectively - [15]). This difference in swelling properties possibly arises from the differences in wood density and wood moisture content ([40]).

Drying properties

As in swelling, the moisture loss was significant in the first days of drying and reduced towards the end of the shrinkage test. The shrinkage of P. halepensis wood was not the same in all three directions with higher dimensional change in the tangential and radial directions than in the longitudinal direction.

The mean values of the radial, transverse, and longitudinal shrinkage of P. halepensis wood are summarized in Tab. 2. The radial and tangential shrinkage values of Algerian P. halepensis wood was 3.76% and 4.76%, respectively (Tab. 2). These results are similar but lower than the Tunisian P. halepensis wood values with a radial shrinkage from 4.4% to 6.0% and a tangential shrinkage from 6.9% to 7.5% ([12]). The Algerian P. halepensis wood also shrinks less than French and Turkish P. halepensis woods in terms of radial, tangential, and volumetric shrinkage values (4.5%, 7.4%, 11.8% and 4.8%, 7.2%, 12.5%, respectively - [39], [15]). The shrinkage properties of Algerian Aleppo pine were also better than black pine (P. nigra) and Italian stone pine (P. pinea) which had radial, tangential, and volumetric shrinkage values of 5.0%, 7.2%, 12.5% and 3.1%, 5.7%, and 8.8%, respectively ([1]).

Shrinkage is affected by factors such as density, moisture content, anatomical structure, mechanical stress and chemical composition of wood ([40]). When wood dries, the free water is removed first; it moves to the surface of wood and evaporates, usually without causing detrimental effect to the wood. When cells do not contain free water, the wood reaches the fiber saturation point (FSP) and if the drying process continues beyond this point, wood starts to shrink. Shrinkage shows a similar anisotropy as that of swelling ([39]). The anisotropy (A) of the shrinkage indicates the dimensional stability of the wood and is calculated by the ratio between the tangential and radial shrinkage values. The wood anisotropy of P. halepensis shrinkage (1.26) is lower than that of other coniferous species such as Pinus pinea (1.53), Pinus pinaster (2), Pinus sylvestris (1.7) or Pseudotsuga menziesii (1.7 - [11]). The low T/R shrinkage ratio indicates that the Algerian P. halepensis wood has a good dimensional stability.

Mechanical properties

The results of the 3-point bending tests on the P. halepensis wood are shown in Tab. 3. The Young’s modulus (MOE) found in this study (17,241 MPa) is considerably higher than the other reported MOE values (between 8,300 and 13,500 Mpa, respectively - [25]). The bending strength (MOR) of the Algerian P. halepensis wood (116 MPa) was also higher than other values reported for the same species (Tab. 3). Different authors found bending strength values between 43 MPa and 138 MPa for P. halepensis wood ([39], [1], [25], [12]). On the other hand, lower MOR values were reported for other pine species such as 82 MPa for Turkish pine (P. brutia) and 100 MPa for Scots pine ([1]). Only the MOR values of black pine (P. nigra: 96-120 MPa) exceeds the bending strength of Algerian Aleppo pine wood ([1]).

Tab. 3 - Test results of 3-point bending of the P. halepensis wood. F is force (N), f is deflection (mm), f1 and f2 are deflections occurred at 10% (F1) and 40% of maximum force (F2), MOR is modulus of rupture (MPa) and MOE is elasticity modulus (Mpa).

| Parameters | Units | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Fmax | N | 2070 |

| fmax | mm | 15.2 |

| f1 | mm | 0.55 |

| f2 | mm | 2.04 |

| F1 | N | 207 |

| F2 | N | 828 |

| MOR | MPa | 116.4 ± 8.5 |

| MOE | MPa | 17520 ± 1500 |

According to these results, it seems that the Algerian P. halepensis has superior mechanical properties (bending strength and Young’s module, respectively) to those of other conifers such as maritime pine (P. pinaster: 80, 8800 MPa), Scots pine (P. sylvestris: 90, 11,900 MPa), Douglas pine (Pseudotsuga menziesii: 85, 12,100 MPa), silver fir (Abies alba: 68, 12,200 MPa) and Norway spruce (Picea abies: 71, 11,000 Mpa - [7]). It is important to note that these results were obtained on wood samples that did not present defects such as knots or resins pockets that could decrease the wood mechanical strength ([40]). For instance, the presence of knots or resins reduced the modulus of elasticity by 15% and the stress at break in bending by 11% compared to the average values recorded on specimens without defects ([25]).

The findings of the physical and mechanical properties of P. halepensis wood need to be interpreted with caution because they are limited with a small number of tests, in this study. However, these results provide a basis for the development of future applications along with the results of thermal behavior.

Thermal behavior

Low-temperature thermal degradation

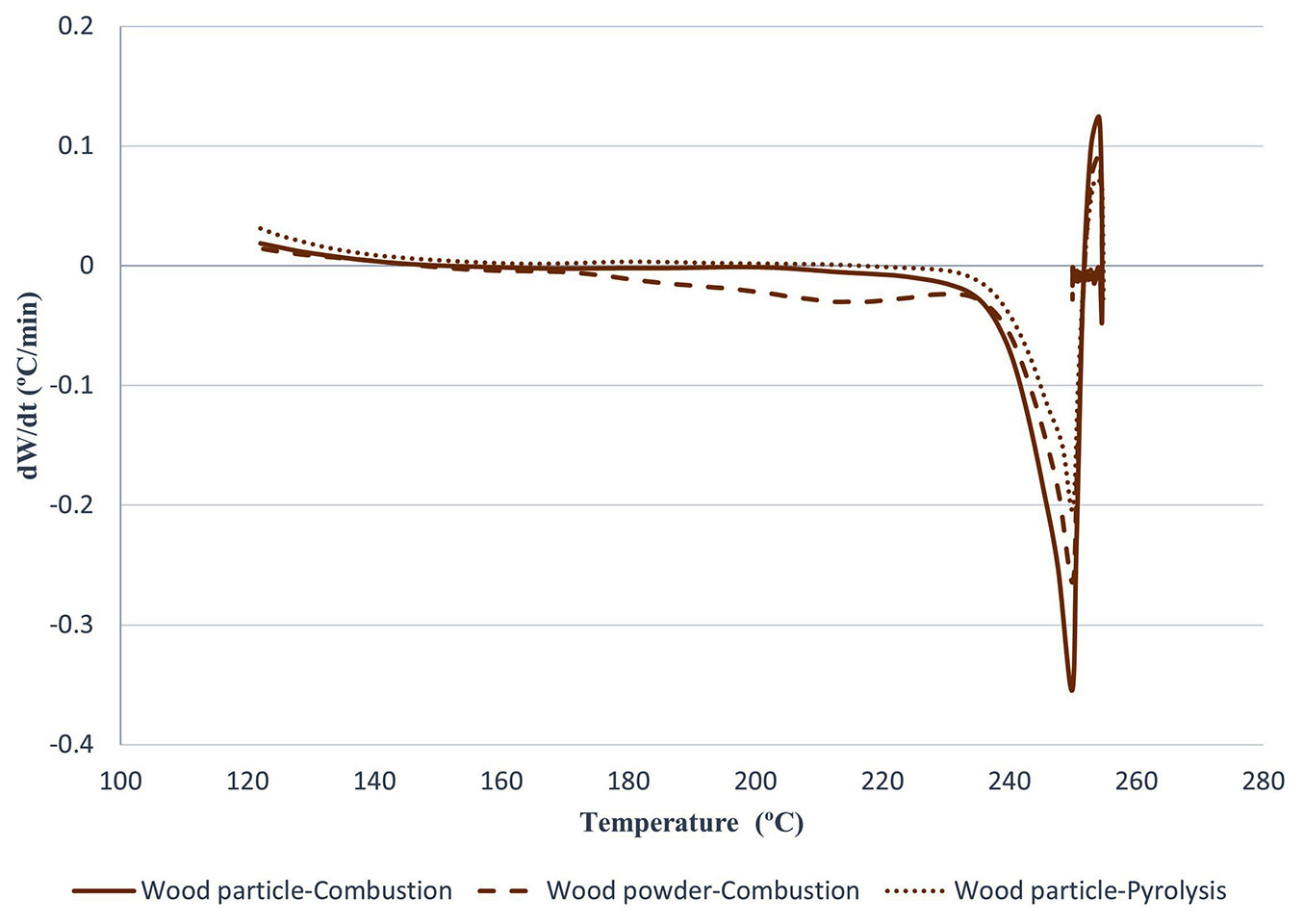

The low-temperature thermal degradation of Algerian P. halepensis wood was investigated between 120 and 250 °C. The mass loss values in combustion were higher in the powder sample than in the particle sample (62.7% and 18.1%, respectively), indicating the occurrence of mass and heat transfer limitations on the latter.

The powder sample started degradation at lower temperatures than the particle sample under pyrolysis conditions (Fig. 4). The thermal degradation rate remained constant after reaching the peak temperature. Pyrolysis of the Algerian P. halepensis wood resulted in 9.4% mass loss under the similar experimental conditions as used for combustion. The mass loss rate was smaller than that of combustion and shifted to the higher temperatures (Fig. 4). The low mass loss values in combustion and pyrolysis imply that Algerian P. halepensis timber structures are likely to be resistant to thermal degradation at low temperatures.

Fig. 4 - Comparative low-temperature thermal degradations of P. halepensis wood particle and wood powder.

Fig. 4shows low-temperature thermal degradations of P. halepensis wood particle and wood powder.

Thermal conductivity

Thermal conductivity is an important property particularly for thermal insulation applications. Tab. 4summarizes the average values of thermal conductivity of the samples of P. halepensis wood veneer. The average thermal conductivity was 0.21 W m-1 K-1. The higher thermal conductivity of P. halepensis wood veneer in the smallest direction compared to longest direction was an interesting result, although the difference was not high (0.08 W m-1 K-1). The thermal conductivity results of this study are in agreement with a previous study ([26]) reporting thermal conductivity values of Algerian P. halepensis wood of 0.18 W m-1 K-1 and 0.28 W m-1 K-1 for parallel and perpendicular directions, respectively. Because of the anisotropy of wood, the thermal conductivity in the perpendicular direction to the fibres is generally smaller than in the parallel direction, while radial and tangential directions show similar thermal conductivities ([21], [38], [35]). The thermal diffusivity of Algerian P. halepensis wood was 0.25 × 10-6 m2 s-1 considering the reported heat capacity of the species ([26] - Tab. 4). The thermal diffusivity of Algerian P. halepensis wood is slightly higher than the average value of wood species (0.16 × 10-6 m2 s-1) but lower than mineral wool (1 × 10-6 m2 s-1 - [35]).

Tab. 4 - Thermal conductivity and thermal resistance of P. halepensis wood veneer in different directions (λ// is the thermal conductivity in longest direction; λ⊥ is the thermal conductivity in smallest direction; R// is the thermal resistance in longest direction; R⊥ is the thermal resistance in smallest direction.

| Parameter | Direction (Units) | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal conductivity | λ// (W m-1 K-1) | 0.17 ± 0.10 |

| λ⊥ (W m-1 K-1) | 0.25 ± 0.11 | |

| Thermal resistance | R// (m2 K W-1) | 0.12 ± 0.09 |

| R⊥ (m2 K W-1) | 0.07 ± 0.10 | |

| Average thermal diffusivity | α (m2 s-1)* | 0.25 ± 0.06 · 10-6 |

The thermal conductivity values of P. halepensis wood veneer found in this study are in the upper range of values reported for wood as shown for example in the Wood Handbook ([35]), which indicates that the thermal conductivity ranges between 0.10 and 0.21 W m-1 K-1 in several wood species. Therefore, the thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity results indicate that P. halepensis wood veneers should be used with insulating core materials such as cork for thermal insulation applications of sandwich panels, where core layer acts as the greatest thermal resistance.

Conclusions

The physicomechanical and thermal properties of Algerian P. halepensis wood were investigated aiming at its use as a component of cork sandwich structures for construction applications. The Algerian P. halepensis wood has a medium density (540 kg m-3), good dimensional stability in swelling and shrinkage, favorable bending properties (116 MPa bending strength and of 17,520 MPa modulus of elasticity) and a good resistance to thermal degradation at low temperatures. The Algerian P. halepensis wood veneer has an average thermal conductivity of 0.21 W m-1 K-1.

The overall results of the study suggest that Algerian P. halepensis wood has a promising potential in the use of face layers in sandwich panel formulations with insulating core layers for the production of structural members and thermal insulation.

Acknowledgements

Umut Sen acknowledges support from FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal) through a research contract (DL 57/2016). The Centro de Estudos Florestais is a research unit funded by FCT (UIDB/00239/2020).

Conflict of Interest

The authors of the article certify that they have no involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Materials Technology Research Laboratory (MTL), University of Science and Technology Houari Boumedienne (USTHB), Bab Ezzouar (Algeria)

Helena Pereira

Centro de Estudos Florestais, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, 1349-017 Lisboa (Portugal)

Research Unit Materials, Processes and Environment, University M’Hamed Bougara, 35000 Boumerdes (Algeria)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Lakreb N, Sen U, Bezzazi B, Pereira H (2022). The physicomechanical and thermal properties of Algerian Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) wood as a component of sandwich panels. iForest 15: 106-111. - doi: 10.3832/ifor3952-015

Academic Editor

Manuela Romagnoli

Paper history

Received: Aug 21, 2021

Accepted: Jan 11, 2022

First online: Mar 21, 2022

Publication Date: Apr 30, 2022

Publication Time: 2.30 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2022

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 40458

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 35951

Abstract Page Views: 2350

PDF Downloads: 1643

Citation/Reference Downloads: 0

XML Downloads: 514

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 1413

Overall contacts: 40458

Avg. contacts per week: 200.43

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2022): 2

Average cites per year: 0.50

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Short Communications

Influence of thermo-vacuum treatment on bending properties of poplar rotary-cut veneer

vol. 10, pp. 161-163 (online: 13 June 2016)

Research Articles

Physical and mechanical characteristics of poor-quality wood after heat treatment

vol. 8, pp. 884-891 (online: 22 May 2015)

Technical Advances

Technical properties of beech wood from aged coppices in central Italy

vol. 8, pp. 82-88 (online: 04 June 2014)

Research Articles

Thermo-modified native black poplar (Populus nigra L.) wood as an insulation material

vol. 14, pp. 268-273 (online: 29 May 2021)

Research Articles

Kinetic analysis of poplar wood properties by thermal modification in conventional oven

vol. 11, pp. 131-139 (online: 07 February 2018)

Research Articles

Physical, chemical and mechanical properties of Pinus sylvestris wood at five sites in Portugal

vol. 10, pp. 669-679 (online: 11 July 2017)

Research Articles

Behavior of pubescent oak (Quercus pubescens Willd.) wood to different thermal treatments

vol. 8, pp. 748-755 (online: 16 February 2015)

Research Articles

Mechanical and physical properties of Cunninghamia lanceolata wood decayed by brown rot

vol. 12, pp. 317-322 (online: 06 June 2019)

Research Articles

Effect of silver nanoparticles on hardness in medium-density fiberboard (MDF)

vol. 8, pp. 677-680 (online: 17 December 2014)

Research Articles

Reversible and irreversible effects of mild thermal treatment on the properties of wood used for making musical instruments: comparing mulberry to spruce

vol. 15, pp. 256-264 (online: 20 July 2022)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword