Changes in moisture exclusion efficiency and crystallinity of thermally modified wood with aging

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 12, Issue 1, Pages 92-97 (2019)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor2723-011

Published: Jan 24, 2019 - Copyright © 2019 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate whether aging affects moisture exclusion efficiency and crystallinity of thermally modified wood. For this purpose, wood blocks of hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), Norway spruce (Picea abies) and oak (Quercus castanifolia), modified at 180 °C for 3 hours inside a ThermoWood kiln were exposed to a six-cycle artificial aging procedure. Aging reduced the efficiency and crystallinity of the modified woods. A significant negative correlation was found between the wood crystallinity and equilibrium moisture content (EMC) which indicates that change in the crystallinity index (CrI) measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD) affects the affinity of wood to moisture. The increased affinity of the modified wood to moisture after aging is probably due to the leaching of thermal degradation products as observed by Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy.

Keywords

Aging, Crystallinity, Moisture Exclusion Efficiency, Thermally Modified Wood

Introduction

The hygroscopicity of wood is responsible for many challenges of using wood for outdoor applications where exposure to high humidity and rain is concerned. Thermal modification is the most widely used commercial process to reduce the affinity of wood to moisture uptake. Reduction in the accessible hydroxyl groups of wood due to thermal degradation of hemicelluloses, increase in the cellulose crystallinity, and crosslinking in lignin were suggested to be the main reasons for reducing the hygroscopicity of wood due to the thermal modification ([12]). It is supposed that irreversible changes in the physical and mechanical properties of a material occur during aging ([33]). Contradictory results were reported for the effect of natural aging on the equilibrium moisture content (EMC) of wood ([20]). However, most literatures found that the EMC of wood decreases with an increase in wood age ([20]).

Crystallinity refers to the amount of crystalline region in the material with respect to the amorphous content. Among wood components, cellulose is semi-crystalline, but hemicelluloses and lignin are amorphous. The crystallinity of wood is often estimated by analytical techniques, such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), FT-IR, carbon-13 NMR and near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy ([23], [11], [18], [27], [22]). The degree of crystallinity has a noticeable influence on different properties of wood, including thermal stability, mechanical strength, hardness, density and hygroscopicity ([11], [22], [27]). A comprehensive literature review conducted by Kranitz et al. ([20]) showed that the natural aging may have different effects on the crystallinity of wood. A number of authors reported an increase in the degree of crystallinity of wood as a result of heat treatment ([21], [6], [34]). An increase in the crystallinity during the early stages of thermal modification, when the mass loss is low, is due to the molecular reorientation rather than the loss of amorphous components (hemicelluloses) of wood ([15]).

Until now, few studies have reported the effect of weathering on the moisture exclusion efficiency of thermally modified wood ([25], [16], [7]) and there is no study exploring changes in the crystallinity of thermally modified wood after aging. It is claimed that thermally modified wood is more resistant to weathering than untreated wood due to largely unleachable weathering products of lignin ([25], [16]). However, an increase in the wettability of the modified wood after re-wetting cycles was reported as a result of artificial weathering and reduction in its anti-swelling efficiency ([16], [7]).

In contrast to artificial weathering, other parameters affecting the service life of a product, such as winter temperatures, thermal degradation and maximum shrinkage, can be simulated by applying artificial aging. Reduction in the moisture exclusion efficiency of thermally modified wood after cycled moisture sorption and water soaking is often explained by the recovery of annealing effects of wood amorphous polymers ([5], [10], [4], [35]). In addition to the annealing effects, the cell wall bulking effect caused by thermal degradation products is responsible for a non-permanent reduction in the moisture sorption of thermally modified wood. The accumulated degradation products can be removed by water soaking, resulting in an increase of EMC. However, none of the above mentioned studies has directly examined the changes in crystallinity of thermally modified wood after artificial aging. Thus, the main purpose of this study is to determine how the crystallinity index (CrI) of thermally modified wood changes due to artificial aging, and to find out if the crystallinity of modified wood contributes to the changes in the moisture exclusion efficiency. Furthermore, our aging process gives more information about the efficacy of thermally modified wood that is affected by freezing or high temperature in addition to wetting-drying cycles.

Materials and methods

Wood sampling and thermal modification

Boards of hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), oak heartwood (Quercus castanifolia) and Norway spruce (Picea abies) with 20 mm in thickness were thermally modified inside a ThermoWood kiln. First, the boards were dried by a fast high-temperature drying process. During the drying phase, the kiln temperature was first raised rapidly to about 100 °C and then increased steadily to 140 °C to reduce the moisture content of wood to almost zero. After drying, thermal modification was carried out at the target temperature of 180 °C for 3 hours. Finally, cooling and conditioning were applied for 24 h to bring the moisture content to about 7%.

Artificial aging procedure

Control and thermally modified specimens were exposed to a six-cycle artificial aging according to V313 procedure, European Standard EN 321. The specimens were exposed to immersion in distillated water at 20 °C for 72 h, freezing at -12 °C for 24 h, drying at 70 °C for 72 h, and settled at room temperature for 4 h.

Measuring moisture exclusion efficiency

Equilibrium moisture content (EMC) of specimens was measured in a climatic chamber at 20 °C and 65% RH. The EMC of aged samples was determined as follows (eqn. 1):

where m1 is the oven dried mass of samples after aging and m2 is the mass after equilibration in the climatic chamber for three weeks. Unaged samples were also used as references for determining the EMC before aging. The moisture exclusion efficiency (MEE) of specimens was then calculated as (eqn. 2):

where Eu and Em are the EMC values of untreated and modified wood, respectively. Five repetitions were used for each treatment.

ATR-FTIR studies

Attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy was used to investigate the chemical changes of wood specimens due to aging. Spectra were recorded on Bruker Tensor 27® ATR-FTIR device equipped with the software OPUS ver. 7.2 (Bruker Optik GmbH, Fällanden, Switzerland). Spectra were baseline corrected by the concave rubber band method (ten iterations, 64 baseline points) and min-max normalized. The FT-IR spectrum was recorded for each sample in the wavenumber range of 4000-400 cm-1 with 64 scans per analysis at spectral resolution of 4 cm-1.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was carried out on wood powder samples with Co Kα radiation (λ=1.78 Å, 40 kV, 30 mA) to quantify the degree of wood crystallinity. Intensities were measured in the range of 5° < 2θ < 50° with scan steps of 0.04°. The crystallinity index (CrI) was calculated base on the following ratio ([30] - eqn. 3):

where I200 is the intensity of the crystalline peak at 2θ = 22.6°, reflecting both crystal and amorphous material, and Iam is the minimum intensity between the 200 and 101 peaks at 2θ = 18.5°, reflecting only amorphous material. Two measurements were performed for each sample group.

Results and discussions

Mass loss

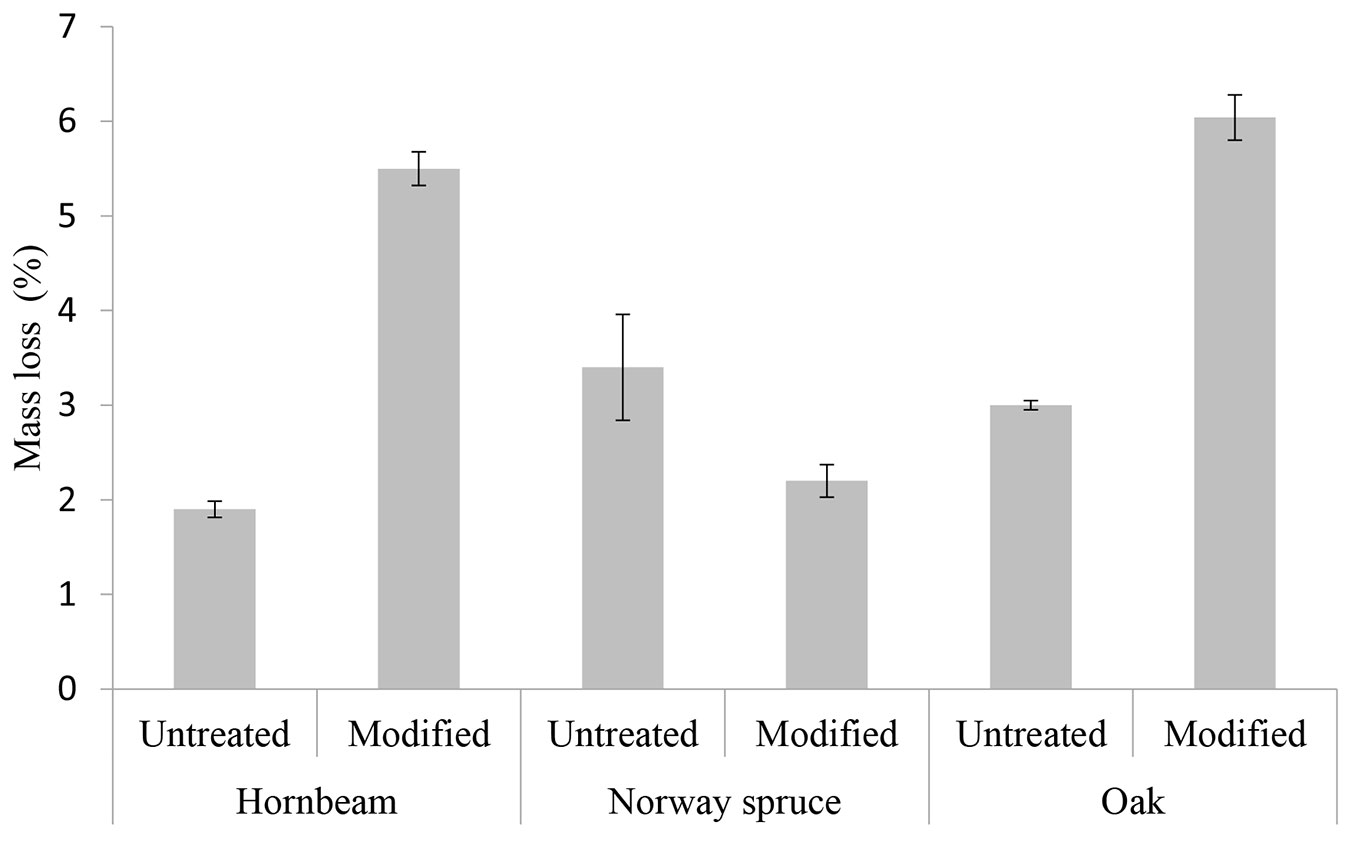

The mass loss ranged from 1.9 to 6% after exposure to six cycles of aging, with the highest value for modified oak (Fig. 1). Except Norway spruce, the mass loss was greater for thermally modified wood compared to the control wood. The mass loss is mainly due to the reduction in the water-soluble extractives of wood specimens during wetting cycles of aging. Thermal modification causes an increase in the extractives content ([7]) which are leach out during aging. Our aging results showed that the greatest leachable materials were formed in oak due to the modification.

Fig. 1 - Mass loss due to artificial aging. Error bars represent the standard deviation of five measurements for each sample group.

Moisture exclusion efficiency

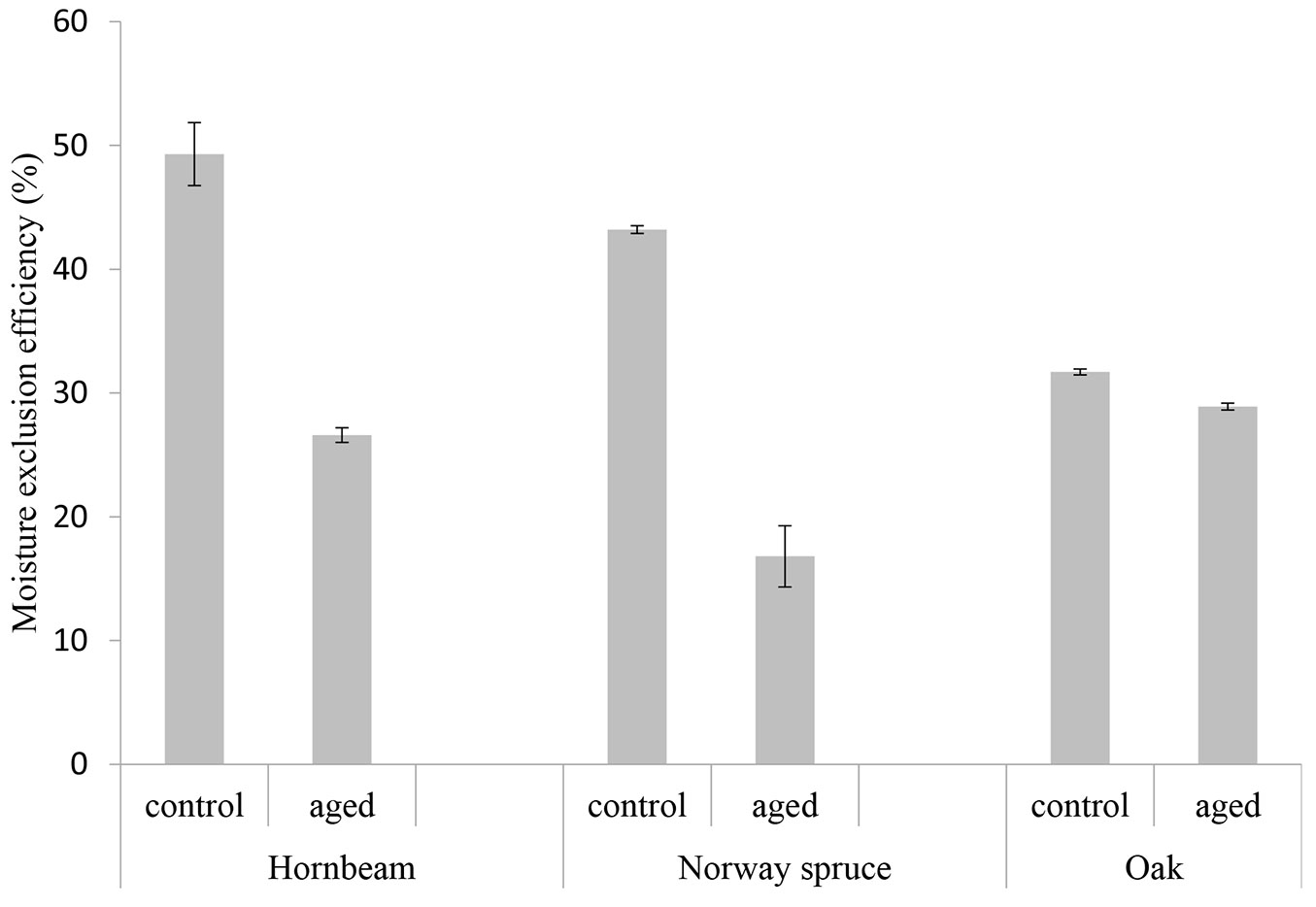

In agreement with a number of previous studies ([12]), all thermally modified woods had an evident lower EMC than the untreated woods, and the best moisture exclusion efficiency (49.3%) was observed in hornbeam. Reduction in EMC due to heat treatment ranges from 0% to 50%, depending on the treatment conditions ([8]). A higher heat-treating temperature causes a greater EMC reduction. Moisture exclusion efficiency (MEE) of the modified wood is mainly due to irreversible chemical changes of the cell wall components and degradation of hemicelluloses. However, the MEE of thermally modified wood specimens seems to be overestimated due to reversible annealing effects caused by drying at elevated temperature (100-140 °C) beyond the softening point of amorphous polymers during the thermal modification process. It is claimed that the reduction in hygroscopicity of thermally modified wood is due to both reversible and irreversible effects, and the annealing of amorphous wood polymers is responsible for the former effect ([10]). The reversible change in the hygroscopicity may also be due to the presence of degradation products of thermal modification, which reduce the wood porosity by occupying the nanopores of the cell walls ([35]). In contrast to the common belief that the hydroxyl groups available for moisture uptake are significantly reduced by the heat treatment, Rautkari et al. ([28]) found a poor correlation between EMC and the accessibility of hydroxyl groups, indicating that there are other mechanisms controlling the EMC in addition to the hydroxyl group accessibility.

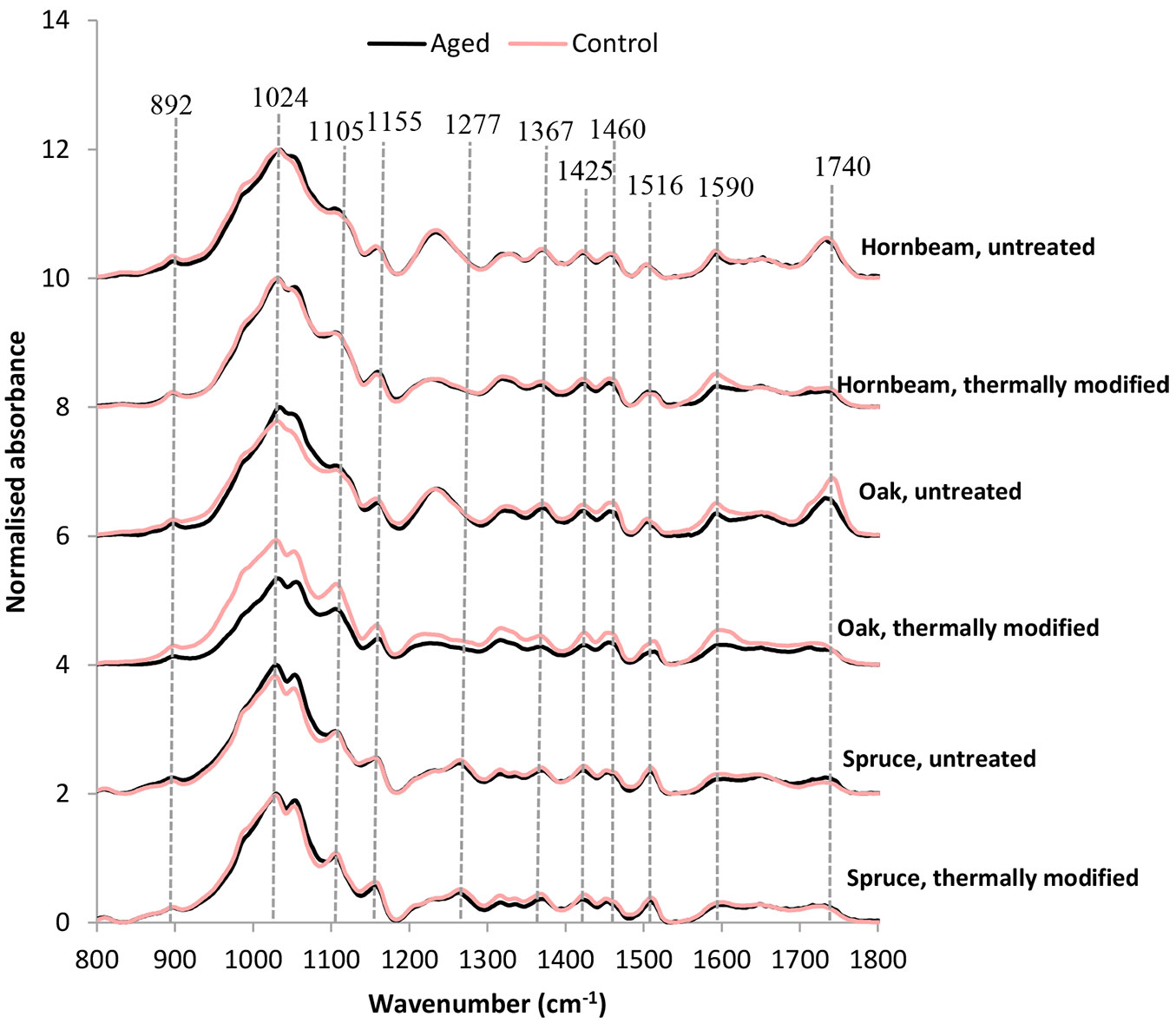

Tab. 1 shows the EMC of wood samples before and after aging. The moisture exclusion efficiency of thermally modified wood due to aging decreased by 8.8 % in oak, 61.1% in Norway spruce and 46.1% in hornbeam (Fig. 2). Literature reviews show contradictory trends concerning the hygroscopic behavior of naturally aged wood, but in most cases EMC slightly decreases with increasing age ([20]). The main reason for the reduction in moisture exclusion efficiency is the leaching of extractives and accumulated thermal degradation products during aging, as observed by ATR-FTIR. Both cell wall bulking and annealing effects on the hygroscopicity of thermally modified wood fully disappeared during water soaking ([5], [3], [35]). However, the drying-related annealing effects can also be partially removed by exposure to the elevated relative humidity. Most of extractives, such as resin acids, disappears from wood after heat treatment ([24]), but new complex polyaromatic compounds are formed due to the degradation of cell wall components ([12]), which can be water soluble. A summary of IR bands observed in the wood samples is given in Tab. 2. An absorption band was observed in the carbonyl group region of wood samples at 1740 cm-1 (Fig. 3), showing a reduction in the peak intensity due to thermal modification, caused by degradation of hemicelluloses. The reduction might also be caused by the leaching of remaining acetic acid in thermally modified wood. As observed for oak, the reduced intensity due to aging confirms the removal of fats and waxes by the aging procedure. The intensity of peak at 1516 cm-1 also was slightly reduced which suggests the removal of aromatic extractives, such as dehydroabietic acid, lignans, and stilbenes ([24]) due to aging. The peak at 1277 cm-1 originated from the C-O stretching vibrations of softwood resin acids ([24]) was observed in Norway spruce even after aging. Removal of extractives was reported to cause an increase in EMC, fiber saturation point (FSP) and dimensional changes of wood ([14]). It is believed that nanopores in the cell wall matrix may be occupied by accumulated degradation products, thereby causing reduction in the hygroscopicity of wood after thermal modification ([35]). Other chemical changes may contribute to the hygroscopicity of aged thermally modified wood, in addition to possible effect of leaching of extractives and thermal degradation products.

Tab. 1 - Mean EMC values (± standard deviation) of wood samples before and after aging.

| Species | Status | EMC (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Aged | ||

| Oak | Unmodified | 9.5 ± 0.02 | 10.7 ± 0.30 |

| Modified | 5.8 ± 0.17 | 7.6 ± 0.41 | |

| Norway spruce | Unmodified | 8.2 ± 0.47 | 10.0 ± 0.30 |

| Modified | 4.7 ± 0.16 | 8.4 ± 0.15 | |

| Hornbeam | Unmodified | 9.6 ± 0.10 | 10.5 ± 0.24 |

| Modified | 5.2 ± 0.47 | 7.7 ± 0.27 | |

Fig. 2 - Moisture exclusion efficiency (MEE, %) of control and aged thermally modified wood. Error bars represent the standard deviation of five measurements for each sample group.

Tab. 2 - Assignment of major absorption IR spectra peaks in wood samples.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Band assignment |

|---|---|

| 1740 | unconjugated C=O stretching |

| 1590 | C=C stretching of the aromatic ring in lignin |

| 1516 | Aromatic skeletal vibration |

| 1460 | C=H deformation (methyl and methylene) |

| 1425 | asymmetric CH2 deformation in cellulose |

| 1367 | CH deformation in cellulose and hemicellulose |

| 1277 | C-O stretching vibrations of softwood resin acids |

| 1155 | C-O-C vibration in cellulose and hemicellulose |

| 1105 | Aromatic skeletal and C-O stretching vibration of polysaccharides and lignin |

| 1024 | C-O stretching in cellulose and hemicellulose |

| 892 | C-H deformation in cellulose |

Fig. 3 - Average ATR-FTIR spectra in the range of 800-1800 cm-1 for control and thermally modified woods before (red line) and after (black line) aging.

Crystallinity

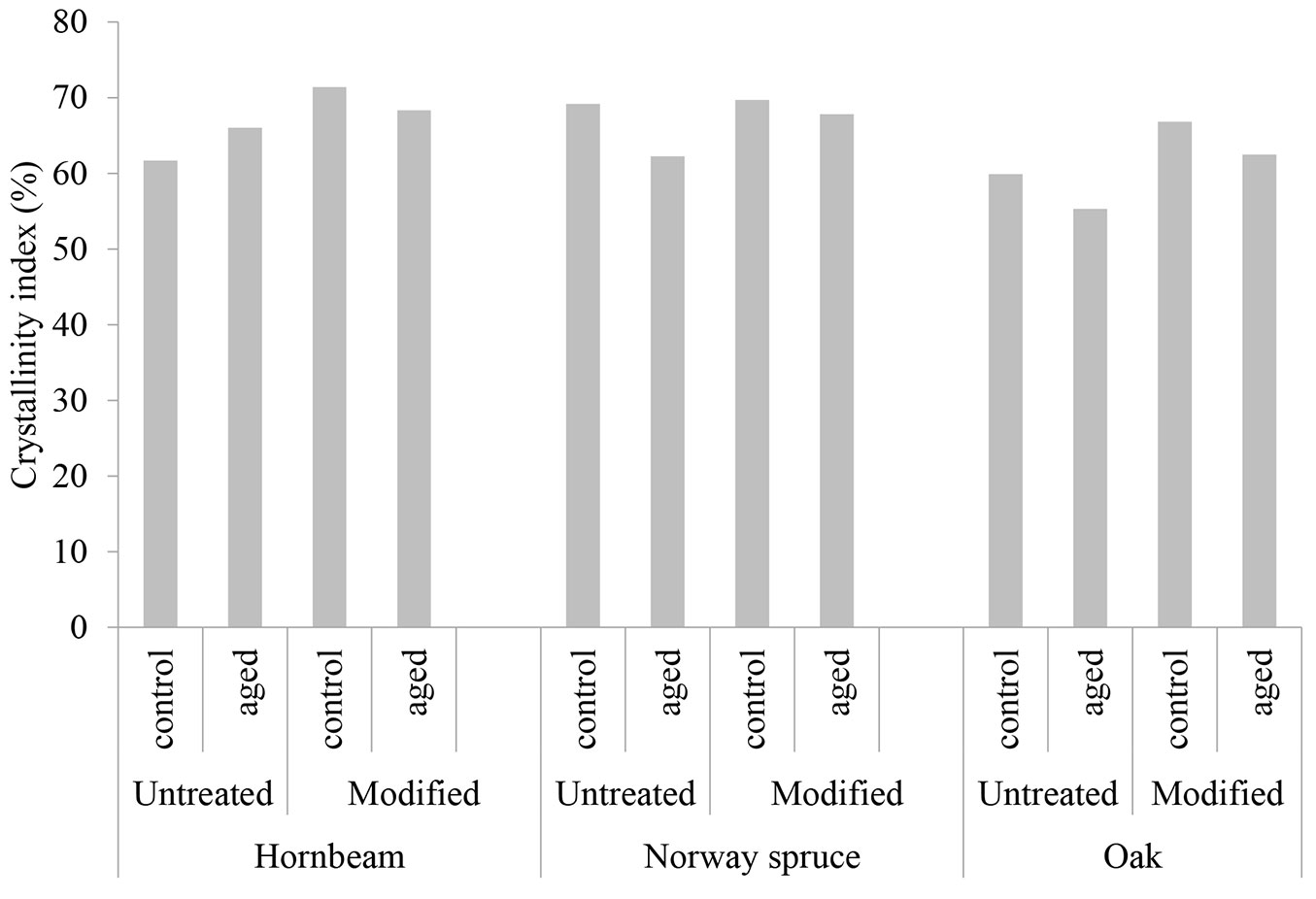

The crystallinity index (CrI) of the wood specimens was increased after thermal modification (Fig. 4), which is in agreement with previous studies ([6], [2], [16]). The decomposition of amorphous regions in cellulose and hemicelluloses, as well as the crystallization of amorphous cellulose due to thermal degradation, causes an increase in crystallinity of the modified wood ([12], [17]). However, it is worth noting that the loss of hemicelluloses due to thermal effects, as confirmed by reduction in the intensity of FTIR peak at 1740 cm-1 (Fig. 3), also leads to the enrichment of the relative crystalline content.

Fig. 4 - Crystallinity index (CrI) of untreated and thermally modified woods before and after aging. Values are the average of two measurements for each sample group.

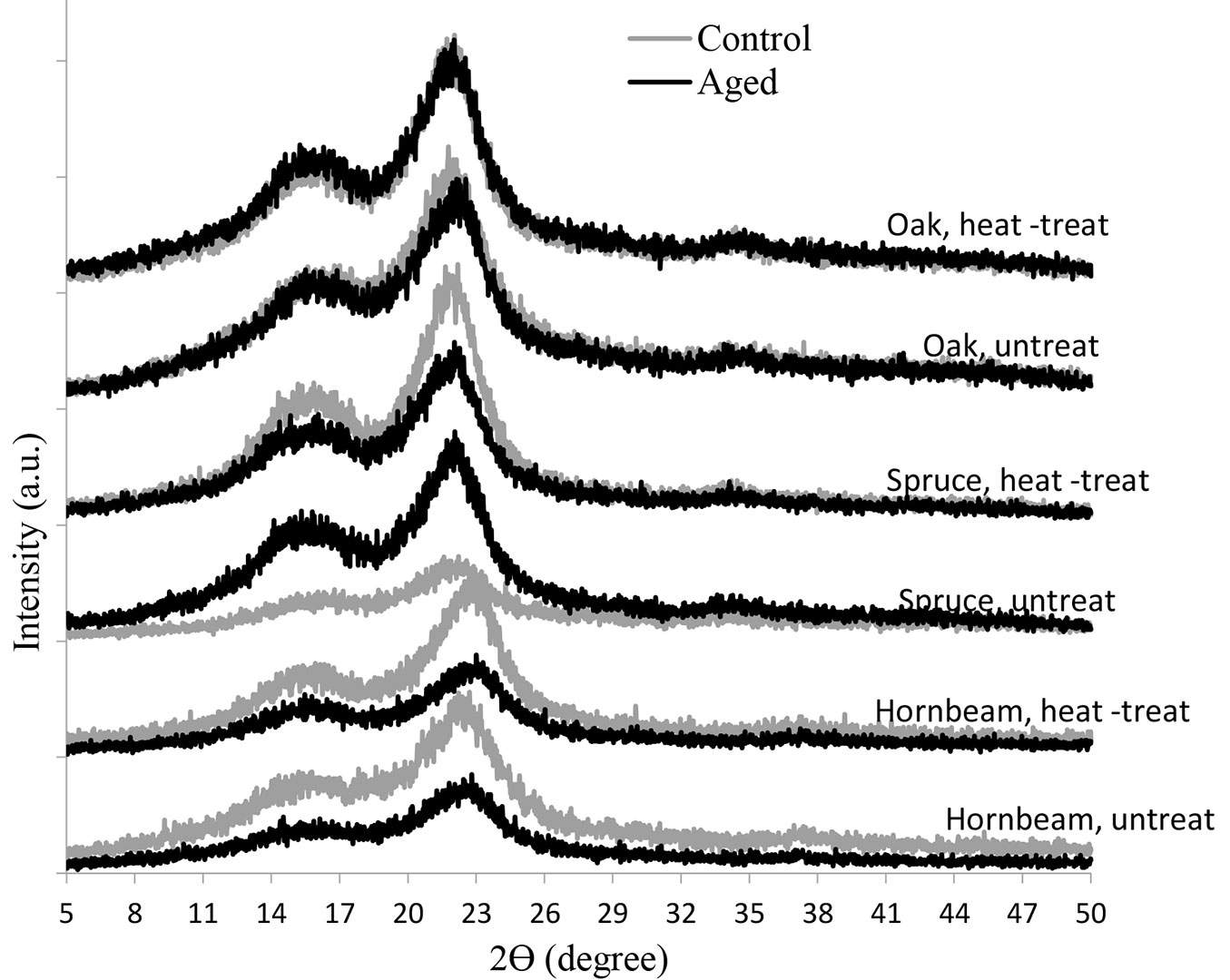

Aging reduced the crystallinity of the modified woods by around 17.1% in hornbeam, 19.1% in Norway spruce and 20.4 % in oak (Fig. 4), probably due to the removal of extractives and the effects of repeated wetting and drying cycles of aging. It has been hypothesized that noncrystalline cellulose forms hydrogen bonds with cellulose at the surface of crystalline region due to the repeated moisture changes ([32]). Drying at high temperatures also results in the cellulose crystallization in the noncrystalline region ([29], [31]). Drying does not alter cellulose crystallinity or cellulose crystalline structure, though it affects the size of microfibril bundles and thus the cellulose accessibility to water ([31]). Random (cold) crystallization in the quasi-crystalline region of wood cellulose may also increase the crystallinity of wood. No changes occurred in the diffraction pattern of wood specimens after aging and the peaks were not shifted (Fig. 5). The crystalline structure of wood cellulose microfibers hinders the access of water molecules to the OH groups. Reduction in the degree of cellulose crystallinity in naturally aged wood of Pinus sylvestris L. was reported to have a major influence on the wood hygroscopicity ([11]).

Fig. 5 - XRD curves of untreated and thermally modified woods before (gray lines) and after (black lines) aging.

Crystallinity index of wood may vary depending on the measurement method. X-ray diffraction is often used for measuring the crystallinity of wood materials ([26], [22], [1]). The crystallinity can be also estimated by using different absorbance ratios in IR spectra, for example 1375 to 1521 cm-1, 1427 to 896 cm-1, 1372 to 2885 cm-1, 1373 to 1350 cm-1, 1373 to 667 cm-1 and 1317 to 1336 cm-1 ([9], [19], [13]). The peak at 1375 cm-1 is caused by symmetric CH deformation in cellulose and the peak at 1512 cm-1 is characteristic of lignin ([22]). The peaks at 1317 cm-1 and 1336 cm-1 are related to crystallised and amorphous cellulose, respectively ([9]). Although the crystallinity index determined by FTIR spectroscopy may have a good correlation with that measured by X-ray diffraction technique ([19]), the latter gives more accurate result. However, it is accepted that XRD technique cannot provide reliable absolute values of crystallinity but only relative values ([26]). Pearson’s correlation test showed that there is a significant negative correlation between the crystallinity and EMC of wood samples (r = -0.69, p< 0.05 - Fig. 6).

Conclusions

We found that the moisture exclusion efficiency and crystallinity of thermally modified wood were reduced due to aging. The increased hygroscopic nature of thermally modified wood after aging confirms the role of reversible effects caused by thermal degradation products in controlling the hygroscopicity. A significant negative correlation, observed between the crystallinity and EMC also indicates that change in the crystallinity index (CrI) of thermally modified wood after aging is one of the several factors which may affect the EMC.

Acknowledgements

Some parts of this study were carried out in Wood Materials Science Group at the Institute for Building Materials at ETH Zurich. The authors are grateful to Prof. Ingo Burgert and Prof. Emil Engelund Thybring.

References

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Akbar Mastouri

University of Tehran, Faculty of Natural Resources, Department of Wood and Paper Science and Technology, Tehran (Iran)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Tarmian A, Mastouri A (2019). Changes in moisture exclusion efficiency and crystallinity of thermally modified wood with aging. iForest 12: 92-97. - doi: 10.3832/ifor2723-011

Academic Editor

Giacomo Goli

Paper history

Received: Jan 06, 2018

Accepted: Nov 10, 2018

First online: Jan 24, 2019

Publication Date: Feb 28, 2019

Publication Time: 2.50 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2019

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 47917

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 39614

Abstract Page Views: 3935

PDF Downloads: 3443

Citation/Reference Downloads: 3

XML Downloads: 922

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 2565

Overall contacts: 47917

Avg. contacts per week: 130.77

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2019): 23

Average cites per year: 3.29

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Review Papers

Moisture in modified wood and its relevance for fungal decay

vol. 11, pp. 418-422 (online: 05 June 2018)

Research Articles

Thermo-modified native black poplar (Populus nigra L.) wood as an insulation material

vol. 14, pp. 268-273 (online: 29 May 2021)

Research Articles

Characterization of VOC emission profile of different wood species during moisture cycles

vol. 10, pp. 576-584 (online: 08 May 2017)

Research Articles

Improving dimensional stability of Populus cathayana wood by suberin monomers with heat treatment

vol. 14, pp. 313-319 (online: 01 July 2021)

Research Articles

Identification of wood from the Amazon by characteristics of Haralick and Neural Network: image segmentation and polishing of the surface

vol. 15, pp. 234-239 (online: 14 July 2022)

Research Articles

NIR-based models for estimating selected physical and chemical wood properties from fast-growing plantations

vol. 15, pp. 372-380 (online: 05 October 2022)

Research Articles

Energy and environmental profile comparison of TMT production from two different companies - a Spanish/Portuguese case study

vol. 11, pp. 155-161 (online: 07 February 2018)

Research Articles

Improving sustainability in wood coating: testing lignin and cellulose nanocrystals as additives to commercial acrylic wood coatings for bio-building

vol. 14, pp. 499-507 (online: 11 November 2021)

Research Articles

Examining the evolution and convergence of wood modification and environmental impact assessment in research

vol. 10, pp. 879-885 (online: 06 November 2017)

Research Articles

Physical, chemical and mechanical properties of Pinus sylvestris wood at five sites in Portugal

vol. 10, pp. 669-679 (online: 11 July 2017)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword