Age trends in genetic parameters for growth and quality traits in Abies alba

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 9, Issue 6, Pages 954-959 (2016)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1766-009

Published: Jul 07, 2016 - Copyright © 2016 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Genetic parameters for growth, stem straightness, survival, wood density and percentage of late wood were estimated in a progeny test of European silver fir (Abies alba Mill.) established in Romania in 1980. The experiment was conducted on 95 families collected from 10 natural stands and five provenance regions, and trait measurements were taken 6-34 years after planting. The family effect was highly significant for 14 traits and significant for one trait. The additive genetic variance increased with age for all the studied traits, and family heritability was higher than individual heritability. Stem diameter, volume per tree, wood density and late wood were the traits with the highest heritability. The trend of individual and half-sib family heritability estimates decreased between 6 and 15 years of age for height and between 6 and 10 years for diameter, while both height and diameter heritabilities were stable at older ages. High age-age genetic correlations were observed, though genetic correlations between growth and wood density were weak. Selection at age 6-10 could increase genetic gain in volume in mature silver fir trees. Selection based on family breeding values combined with within-family selection is recommended to maximize genetic gain in breeding activities in silver fir.

Keywords

Age-age Correlations, Genetic Gain, Heritability, Optimum Age, Progeny Trial, Silver Fir

Introduction

European silver fir (Abies alba Mill.) is one of the most important forest species in Romania, both for economic and ecological purposes. It covers about 5% of the national forest area (approximately 292.000 ha), ranking second after Norway spruce among coniferous species ([41]). Silver fir grows in mixed mountain forests along with European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.), Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) and other deciduous species. Its natural range in Romania is discontinuous, reaching the maximal spread in the Eastern Carpathians, while it shows a very fragmented distribution in the Southern Carpathians, Apuseni and Maramures Mountains. Silver fir timber has multiple uses, such as construction wood, furniture, plywood, pulpwood, etc. Also, through a very deep rooting system, it contributes to the stability of mountain ecosystems against windfall, especially in pure spruce stands.

The first breeding programme of European silver fir in Romania started in the 1980s at the Forest Research and Management Institute by establishing 12 seed orchards and 10 provenance trials, with 33 autochthonous and 27 foreign provenances, and 1 progeny trial. The next experiment series were initiated in 2007-2008, comprising five full-sib trials generated by control pollination in seed orchards, and in 2010, comprising two nursery tests with open-pollinated progeny ([36]). The results of the first experiment series were published by Damian & Leandru ([6]), Deaconu ([7]), Mihai et al. ([34]), Mihai ([35]) and have focused mainly on inter-population variation and selection of the best seed sources. Regarding intra-population genetic variation and genetic parameters estimates, the only data published were based on assessments at the age of 25 years ([34]). Therefore, there are no comprehensive analysis of the inter-individual variability and the time trend of genetic parameters of silver fir in Romania.

The success of a breeding strategy for any species depends on reliable information of the genetic parameters and pattern of variation of characters for which selection will be made ([38]). Thus, the more accurate estimates of genetic parameters are the more realistic predictions of times and costs involved in a breeding programme will be. Moreover, the choice of traits and the optimum age for selection are crucial for the long-term efficiency of breeding programmes ([49]). In general, growth, stem straightness and wood quality had the highest priority in most breeding programmes of forest tree species ([10], [19], [8], [43], [42], [48]).

Most breeding programmes involves tree selection at juvenile age. The time trend of genetic parameters is essential to determine the optimal selection age ([22]). Early selection of juvenile trees can reduce the generation time and increase the gain per year. However, too early selection may lead to poor and unreliable estimates of the gain expected in terms of mature performances of trees ([8]). Also, genetic and phenotypic relationships among different traits or ages of measurement are used to develop selection indices, to maximize the genetic gain and to evaluate efficiency of selection.

Despite the economic importance of silver fir, little data have been published regarding genetic parameters of its traits ([50], [2], [18], [34], [3], [36]). Most of the studies presented results from provenance trials ([33], [17], [11], [30], [47], [21], [27]). Although a number of studies in the literature have documented the time trends of genetic parameters in tree species such as Scots pine ([26]), Norway spruce ([23]), loblolly pine ([44]), no such data are available so far for European silver fir.

To address these problems, the objectives of this paper are: (1) to evaluate the variability and estimate the variance components and heritability for growth, wood quality traits and survival at ages 34 years in the progeny trial from the above-mentioned first experiment series; (2) to estimate the trait-trait and age-age genetic correlations; (3) to assess the early selection efficiency and determine the optimum age of selection; and (4) to estimate the genetic gains. The results will be discussed in relation to their implications and genetic strategies for future breeding activities of silver fir.

Materials and methods

Genetic material, experimental design and measurements

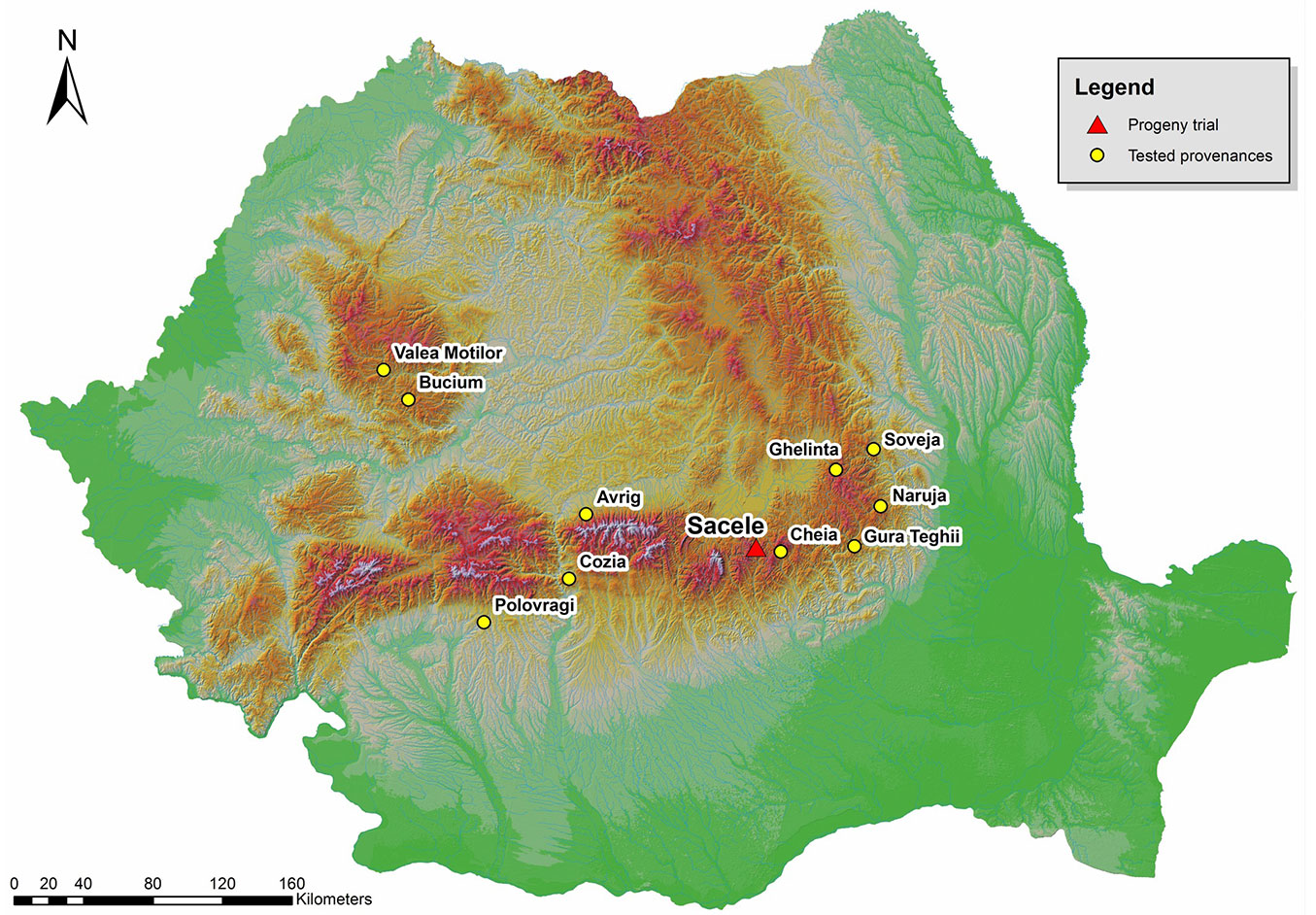

Progeny from 95 open-pollinated silver fir trees were tested in a half-sib trial established in 1980 in the Sacele Forest District (central Romania). Mother trees were selected from 10 natural stands and five provenance regions (Fig. 1). The trial is situated in the deciduous and coniferous mixed layer at 45° 48′ N latitude, 25° 72′ E longitude and elevation of 1225 m a.s.l.

The experimental design of the progeny test was a randomized complete block design. Each of the 10 provenances was represented by 10 families with five seedlings per plot, in four blocks. Out of the original 100 half-sib families, 95 have survived and were included in this study. All measurements were carried out accordingly with the IUFRO methodology. The traits analyzed were: height (in meters) at ages 6, 10, 15, 25 and 34 years (HT6, HT10, HT15, HT25, HT34, respectively); root collar diameter (cm) at ages 6, 10 and 15 years (DRC6, DRC10, DRC15); diameter at 1.30 m above the ground (in cm) at ages 25 and 34 years (DBH25, DBH34); volume (dm3) at age 34 years (VOL34); stem straightness (STR34); wood density (DENS34) in g/cm3; percentage of late wood (LW34); and survival (%) at age 34 years (SURV34). Stem straightness was assessed on a 1-3 scale (1 = straight; 2 = slightly curved; 3 = sinuous). The density was determined on wood samples extracted by a Pressler drill at 1.30 m of height following the formula reported by Dumitriu-Tataranu et al. ([12]). Late wood was measured using the Lintab® equipment (RinnTech e.K., Heidelberg, Germany) and the software package TSAP-Win® ver. 0.53 (RinnTech), with an accuracy of 0.001 mm.

Statistical analysis

For each trait, the linear mixed model included random effects for provenance, family, family × block and within-plot as well as fixed effects for blocks. The variance components were estimated using the Univariate GLM and VARCOMP functions of the statistical package SPSS® v. 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The statistical analysis was based on individual tree measurements using the following linear model (eqn. 1):

where Yijkl is the effect of the kth tree in the jth family in the lth provenance in the ith block, μ is the overall mean, Ri is the fixed effect of the ith block, Pj is the fixed effect of the jth provenance, Fk is the random effect of the kth family NID ~ (0, σ2F), FRik is the interaction of the kth family and ith block with NID ~ (0, σ2plot), and eijkl is the random error associated with ijklth trees with NID ~ (0, σ2e)

The assumptions of the model were checked by examining the residual plots. The family effects are assumed to be random and are associated with the average genetic effects of the open-pollinated families. We considered open-pollinated families as true half-sib families and, consequently σ2A = 4σ2F, where σ2A is the additive genetic variance and σ2F is the family variance component.

The narrow-sense individual heritability (h2i) and half-sib family mean heritability (h2HS) were calculated as follows ([25], [40] - eqn. 2, eqn. 3):

where σ2Ph1 and σ2Ph2 are the total and family mean phenotypic variances, respectively, σ2A is the additive genetic variance, σ2F is the family variance component, σ2plot is the family × block interaction variance component, σ2w is the within-plot variance, n is the number of seedlings per plot, and r is the number of blocks.

Standard errors of heritability were estimated according to the Dickerson’s formulas ([9]) by assuming that the denominator is a constant (eqn. 4, eqn. 5):

The genetic gains were calculated both at the family and individual levels for different breeding strategies ([13]). Genetic gains from mass selection ΔG1 (forward selection) from half-sib family selection ΔÂÂG2 (backward selection) were estimated as (eqn. 6, eqn. 7):

The selection intensity i was 1.996 and 1.705 for half-sib family selection (select top 5% and 10% of families) and 1.867 and 1.638 for individual selection (select top 5% and 10% of trees within each half-sib families - [4]).

To compare the level of additive genetic variance in each trait independent of their means, the additive genetic coefficient of variation (CV, %) was calculated as follows ([5] - eqn. 8):

where μ is the phenotypic mean of the trait.

Genetic correlations were calculated as the ratio of the covariance between traits (numerator) and the square root of the product of their additive genetic variances (denominator - [14]).

Results

Variance components and heritability

In general, results of the analysis of variance at different ages from previous studies reported that provenance effect was moderately significant for all the studied traits ([34], [35]). In this study, the provenance effect was not significant for the trais DBH34, SURV34 and LW34.

The provenances showing the highest volume growth at age 34 were Bucium, Cheia, Avrig and Naruja, while provenances Ghelinta, Gura Teghii and Soveja showed poor growth performances.

Variance components and heritability estimates are listed in Tab. 1. The results indicated that contribution of the additive genetic variance (σ2A) to the total phenotypic variance (σ2Ph) varied between 2% for STR34 and 71% for DRC6. Additive genetic variance is greater for stem diameter than for height in all measurement years, ranging 23-71% for stem diameter and 13-61% for height. An increasing trend of additive genetic variance with age was observed for both traits. The rate of increase was slow up to ages 10-15, and steeper at later ages.

Tab. 1 - Additive genetic variance (σ2A), phenotypic variance (σ2Ph), individual tree heritability (h2i) and family mean heritability (h2HS) and their standard errors for the studied traits at different ages in silver fir progeny test. The proportion (%) of additive genetic variance out of the total phenotypic variance is given in brackets.

| Traits | Mean | CV | σ2A (%) |

σ 2 Ph |

h 2 HS |

h 2 i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT6 | 0.68 | 32 | 0.029 (61) | 0.047 | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 0.61 ± 0.09 |

| HT10 | 1.75 | 16 | 0.083 (25) | 0.330 | 0.47 ± 0.20 | 0.25 ± 0.11 |

| HT15 | 4.28 | 8 | 0.127 (13) | 0.938 | 0.30 ± 0.30 | 0.14 ± 0.13 |

| HT25 | 10.03 | 6 | 0.367 (17) | 2.204 | 0.28 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.06 |

| HT34 | 12.83 | 7 | 0.718 (18) | 4.076 | 0.34 ± 0.12 | 0.18 ± 0.06 |

| DRC6 | 0.21 | 39 | 0.005 (71) | 0.007 | 0.67 ± 0.06 | 0.71 ± 0.06 |

| DRC10 | 5.04 | 15 | 0.588 (22) | 2.669 | 0.42 ± 0.22 | 0.22 ± 0.12 |

| DRC15 | 6.64 | 14 | 0.853 (21) | 4.120 | 0.42 ± 0.21 | 0.21 ± 0.11 |

| DBH25 | 13.73 | 12 | 2.784 (21) | 13.335 | 0.37 ± 0.12 | 0.21 ± 0.07 |

| DBH34 | 16.12 | 14 | 4.795 (23) | 20.716 | 0.41 ± 0.12 | 0.23 ± 0.07 |

| VOL34 | 151.33 | 29 | 1.884 (23) | 8.132 | 0.40 ± 0.12 | 0.23 ± 0.07 |

| STR34 | 1.38 | 6 | 0.007 (2) | 0.390 | 0.05 ± 0.08 | 0.20 ± 0.03 |

| DENS34 | 0.36 | 7 | 0.001 (28) | 0.002 | 0.40 ± 0.24 | 0.28 ± 0.17 |

| LW34 | 20.54 | 5 | 13.542 (5) | 46.933 | 0.32 ± 0.26 | 0.29 ± 0.17 |

| SURV34 | 61.55 | 12 | 56.321 (15) | 365.808 | 0.32 ± 0.00 | 0.15 ± 0.00 |

The level of additive genetic variance of each trait was revealed by CVs (Tab. 1). The CVs ranged from 5 to 39%, depending on the analyzed trait, and growth at early ages had higher CVs. Additive genetic CVs displayed a decreasing trend with age for growth characters. For both total height and stem diameter, the decreasing trend was sharp up to ages 10-15 but was nearly constant thereafter. Thus, the CV of the total height decreased from 25% at age 6 to 7% at age 34, and the diameter decreased from 33% to 14% at the same age.

The narrow-sense individual heritability estimates ranged from 0.14 for HT15 to 0.71 for DRC6 (Tab. 1). The half-sib family heritability ranged from 0.05 for STR34 to 0.67 for DRC6. Except for DRC6, the family heritability was higher than individual heritability. Also, the heritability for overall DRC and DBH were higher compared to overall HT. Wood density, late wood, diameter and volume per tree were the silver fir traits showing the highest heritability for the entire period analyzed. A sudden decrease could be observed between 6 and 15 years both for individual and half-sib family heritability of the growth traits. After age of 15, a stabilization of these parameters was observed.

Trait-trait family mean correlations

Family mean correlations between the studied traits are reported in Tab. 2. The parameters were calculated based on family means. Among all, those with special interest for breeding are the parameters showing significant correlation between growth traits on one hand and wood density, survival, and stem straightness on the other, or between wood density and survival. However, correlations obtained between HT34, DBH34, VOL34 and DENS34 were low and negative, with values ranging between -0.25 and -0.27. Moreover, a negative though weak correlation between density and survival was also observed. In addtion, there were positive correlations between STR34 and both DENS34 and LW34. Correlations between wood density and the percentage of late wood were positive and high. Contrastingly, weak correlations were found between survival and the other studied traits.

Tab. 2 - Trait-trait genetic correlations in silver fir progeny test. Wood density was negatively correlated with growth, though the correlation was weak.

| Traits | DBH34 | VOL34 | STR34 | SUPR34 | DENS34 | LW34 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT34 | 0.50 | 0.51 | -0.18 | 0.02 | -0.27 | -0.43 |

| DBH34 | - | 0.50 | -0.10 | 0.02 | -0.26 | -0.26 |

| VOL34 | - | - | -0.04 | 0.01 | -0.25 | -0.22 |

| STR34 | - | - | - | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.35 |

| SUPR34 | - | - | - | - | -0.01 | -0.05 |

| DENS34 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.54 |

Age-age family mean correlations

To determine the relationships between traits evaluated at age 34 and earlier ages, the family mean age-age correlations were estimated (Tab. 3). High age-age genetic correlations were obtained for HT, DBH and VOL, while genetic correlations for HT and DBH at age 34 and with age 6 were weak. As expected, HT at age 34 showed a higher correlation with the same parameter at age 25, though correlations decreased as age difference increased. The age-age correlations between VOL34 and either total height or stem diameter also increased over time. The family mean age-age correlations between HT were much higher than those for stem diameter measured at the same ages. Therefore, both height and stem diameter could be considered as effective selection criteria in silver fir.

Tab. 3 - Age-age additive genetic correlations from silver fir progeny test. As expected, correlations generally decreased as the difference in age increased.

| Traits | HT10 | HT15 | HT25 | HT34 | DRC6 | DRC10 | DRC15 | DBH25 | DBH34 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT6 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.21 |

| HT10 | - | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.42 | 0.34 |

| HT15 | - | - | 0.98 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.58 | 0.50 |

| HT25 | - | - | - | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.65 |

| HT34 | - | - | - | - | 0.22 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| DRC6 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.17 |

| DRC10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.83 | 0.46 | 0.36 |

| DRC15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.55 | 0.44 |

| DBH25 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.48 |

Genetic gain

The genetic gain was calculated for stem diameter and total height as the deviation (%) from population means at age 6, 10, 15, 25 and 34 years after planting. Genetic gain varied with age, selection method, selection intensity and analyzed traits. Regardless of the selection method or age, the genetic gain was higher for stem diameter than for total height. For all traits, the estimates of genetic gain achievable through individual tree selection were greater than that attainable from half-sib family selection. The likely reason is that the selection intensity was much higher for individual trees. This is consistent with the higher genetic variation of silver fir at inter-individual level compared with inter-population level, already reported in many studies ([28], [24], [31], [45]).

The estimates of genetic gain at 34 years after planting for both family and individual selection are presented in Tab. 4. If the best 5% or 10% of individuals within the half-sib families were selected, a genetic gain of 5% for HT34, 12-11% for DBH34 and 26-23% for VOL34 could be achieved. The family selection at the same intensities could produce a genetic gain of 4-3% for HT34, 9-7% for DBH34 and 18-15% for VOL34. In terms of selection timing, a decrease of genetic gain after the age of 6 was observed. However, the genetic gain was quite stable between age 15 and 34 both for total height and stem diameter (Tab. 4).

Tab. 4 - Genetic gain (%) by selection of the best 5% or 10% families and individuals within families at the age of 34 for silver fir.

| Trait | Family 5% | Family 10% | Within 5% | Within 10% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Stem diameter | 9 | 7 | 12 | 11 |

| Volume | 18 | 15 | 26 | 23 |

| Stem straightness | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Density | 5 | 4 | 7 | 6 |

The results suggested that the optimal time for early selection based on height and diameter is between 6 and 10 years after planting. Genetic gain at age 10 was 15-13% for total height and 13-12% for diameter by individual tree selection and 11-10% for total height and 10-8% for diameter by family selection. Although family mean correlations between wood density and growth traits were not strong, if direct selection would be done based on wood density, the estimated genetic gain would be between 4 and 7%. Therefore, selection can be done at the family level, but also by selecting the best individuals within each family. Indeed, the selection of best families combined with within-family individual selection is expected to yield an increased genetic gain.

Discussion

To our knowledge, no reports on the age trends of genetic parameters for growth and quality traits in European silver fir have been published in the literature so far. Despite our results are based on a single progeny test established at one site, several relevant implications for silver fir breeding and forest management can be drawn from this study, as the genetic parameter assessment carried out is based on a very large number of measurements and tested families over a period of 28 years.

The moderate differences found among provenances and the highly significant differences among half-sib families are in agreement with previous studies in silver fir, which reported a high degree of variation within populations as compared with the inter-population variation ([29], [37], [28], [24], [31], [45]). in fact, the family effect was the most important source of variation for growth, survival and wood quality traits over the entire analyzed period. The observed family differences were small only for stem straightness.

The additive genetic variance for growth traits increased moderately from age 6 up to ages 10-15, and then increased rapidly later; consequently, the additive genetic CV decreased over time, becoming stable after 10 years of age for DBH and 15 years for HT.

The narrow-sense individual heritability decreased from 0.61 at age 6 to 0.14 at age 15 for HT, and from 0.71 to 0.21 for DBH at the same ages. A similar pattern was also observed for the family heritability, which decreased from 0.61 to 0.30 for HT and from 0.61 to 0.42 for DBH at age 6 and 15, respectively. At older ages, the genetic parameters for growth traits became stable over time. Such decrease in heritability could be due to the increased noise by age. Indeed, the progeny trial we analyzed has not been thinned since its establishment. As trees get older they compete for light and water availability. At 34 years of age, the diameter at breast height, volume per tree and wood density are the most heritable traits in silver fir. The heritability estimates suggest a strong genetic control for such traits and, consequently, sufficient chances of success should be ensured using the different selection methods in breeding programs.

In this study, genetic parameter estimates for growth traits were affected by age to a fairly large extent. Similar patterns of variation in genetic parameters were also observed for other species. For example, Hodge & White ([22]) and Dieters ([10]) reported a high height heritability at early ages in slash pine, but a slight decline after age 10. Contrastingly, Haapanen ([20]) found heritability to be fairly constant with age in Pinus silvestris L. For many tree species, juvenile-mature phase change varies according to genetic patterns with age and environmental characteristics of the traits considered. Franklin ([16]) named it the “Mature Genotypic Phase”, and it could explain the intensification of growth and the decline of the heritability that occurs in some conifer species. Silver fir is a species with slow growth up to 10-15 years, and the general increasing trend of additive variance after this age may be a side effect of competition. Foster ([15]) concluded that competition affects both variances and heritability. Furthermore, such changes in genetic parameters are also expected because of different genes involved in the expression of the studied traits at different ages and developmental stages ([39]).

The efficiency of early selection in breeding programs strongly depends on the genetic age-age correlation. Although we used family means to calculate trait-trait and age-age correlations, they can be considered gross estimate of genetic correlations when the number of family and their size are large enough ([32]). All within-family age-age average correlations for height and stem diameter were significantly different from zero, and high juvenile-mature correlations were observed for total height, diameter and volume. As expected, positive correlations were obtained between DBH and HT, while no significant correlations between survival and the other traits were observed. The correlations between growth traits and wood density were negative but statistically non-significant. These results are in accordance with those reported for other species ([19]). Therefore, height, diameter and density could probably be incorporated into a selection index.

For breeding programmes of forest tree species, assessing the trends of variance components, heritability and genetic correlations over time is crucial to optimize early selection and develop effective breeding and testing strategies ([1], [46]). Taking into account the variation patterns of genetic parameters observed in this study, the optimum time for early selection based on height and diameter is between 6 and 10 years after planting. Selection at these early ages will lead to a greater genetic gain in volume of mature silver fir trees. Regardless of age, the genetic gain is expected to be higher for DBH and VOL than for HT.

Breeding could be possible by selecting both the most valuable families and the most valuable individuals within the best families. Comparison of the genetic gain calculated by different selection strategies indicated that forward selection based on family breeding values (mid-parent breeding values) and within-family selection can be usefully combined in breeding activities.

Conclusions

The experiment reveal a large genetic variability at both the seed source and half-sib progeny levels, which can be exploited in breeding programmes and reforestation practices. The provenances showing the best growth are recommended to be designated as tested seed sources and their reproductive material to be used in artificial reforestation. Our results highlighted a high genetic control for growth and quality traits in silver fir, and a large genetic gain can be achieved on the basis of these traits. The high age-age correlation observed allows trees to be selected at early ages, and the genetic gain in mature trees can be maximized by selection on diameter and height as early as 6-10 years after planting.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out within the GENCLIM project financed in Partnership Program by the National Authority for Scientific Research in Romania. The authors also thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Supplementary Material

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Ionel Mirancea

“Marin Dracea” National Institute for Research and Development in Forestry, Department of Forest Genetics and Tree Breeding, B-dul Eroilor 128, 077190 Voluntari (Romania)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Mihai G, Mirancea I (2016). Age trends in genetic parameters for growth and quality traits in Abies alba. iForest 9: 954-959. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1766-009

Academic Editor

Fikret Isik

Paper history

Received: Jul 13, 2015

Accepted: Apr 04, 2016

First online: Jul 07, 2016

Publication Date: Dec 14, 2016

Publication Time: 3.13 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2016

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 49980

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 41190

Abstract Page Views: 3202

PDF Downloads: 4173

Citation/Reference Downloads: 54

XML Downloads: 1361

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 3533

Overall contacts: 49980

Avg. contacts per week: 99.03

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2016): 13

Average cites per year: 1.30

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Patterns of genetic variation in bud flushing of Abies alba populations

vol. 11, pp. 284-290 (online: 13 April 2018)

Research Articles

Genetic variation and heritability estimates of Ulmus minor and Ulmus pumila hybrids for budburst, growth and tolerance to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi

vol. 8, pp. 422-430 (online: 15 December 2014)

Research Articles

Seedling emergence capacity and morphological traits are under strong genetic control in the resin tree Pinus oocarpa

vol. 17, pp. 245-251 (online: 16 August 2024)

Research Articles

Comparison of genetic parameters between optimal and marginal populations of oriental sweet gum on adaptive traits

vol. 11, pp. 510-516 (online: 18 July 2018)

Research Articles

Genetic variation of Fraxinus excelsior half-sib families in response to ash dieback disease following simulated spring frost and summer drought treatments

vol. 9, pp. 12-22 (online: 08 September 2015)

Research Articles

Genetic control of intra-annual height growth in 6-year-old Norway spruce progenies in Latvia

vol. 12, pp. 214-219 (online: 25 April 2019)

Research Articles

Stability analysis and selection of optimal Eucalyptus urophylla × E. grandis families

vol. 18, pp. 293-300 (online: 20 October 2025)

Research Articles

Genetic diversity of core vs. peripheral Norway spruce native populations at a local scale in Slovenia

vol. 11, pp. 104-110 (online: 31 January 2018)

Review Papers

Genetic diversity and forest reproductive material - from seed source selection to planting

vol. 9, pp. 801-812 (online: 13 June 2016)

Research Articles

Impact of inbreeding on growth and development of young open-pollinated progeny of Eucalyptus globulus

vol. 15, pp. 356-362 (online: 20 September 2022)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword