Genetic diversity and forest reproductive material - from seed source selection to planting

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 9, Issue 5, Pages 801-812 (2016)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1577-009

Published: Jun 13, 2016 - Copyright © 2016 SISEF

Review Papers

Abstract

How much of genetic diversity is desirable in mass production of forest reproductive material? How mass production of forest reproductive material reduces genetic diversity? Relation between genetic diversity and mass production of forest reproductive material is discussed in a holistic manner. In industrial forest plantations, narrow genetic diversity is desirable and reproductive material is produced at clone level. On the other hand, in conservation forestry a wide genetic diversity is imperative. Beside management goals, a desirable level of genetic diversity is related to rotation cycle and ontogeny of tree species. Risks of failure are lower in short rotations of fast growing species. In production of slow growing species, managed in long rotations, the reduction of genetic diversity increases the risk of failure due to causes unknown or unexpected at the time of planting. This risk is additionally increased in cases of seed transfer and in conditions of climate change. Every step in production of forest reproductive material, from collection to nursery production, has an effect on genetic diversity mainly by directional selection and should be considered. This review revealed no consistent decrease of genetic diversity during forest reproductive material production and planting.

Keywords

Genetic Diversity, Forest Reproductive Material, Seed Production, Seedling Production, Directional Selection

Introduction

Genetic diversity (GD) provides the basis for adaptation and resistance to stress and changing environment, and is therefore essential for the long-term survival of forests ([11], [123]). High genetic variability allows natural selection to result in adaptation ([121]). A large variation increases chances that at least some individuals in a population are capable to adapt to new environmental conditions. A high GD during artificial establishment of new forest can lead to reduced productivity, but its absence can lead to total failure. Ensuring a minimum level of genetic diversity in founder populations is particularly important in restoration projects ([141]).

There is no risk of losing genetic resources if forest populations regenerate spontaneously ([51]). However, GD may be reduced due to natural processes or anthropogenic influence. The highest pressure is on species with medium ecological amplitude, habitat fragmentation and shortened or absent gene flow, which is instead needed for the maintenance of high GD ([45]). In addition to habitat fragmentation, forest management, which selectively removes trees and their genes from the forest (dysgenic selection), may affect the gene pool of forests ([35], [123], [135]), usually lessening the number and frequency of rare alleles, thereby lowering the estimates of future genetic potential ([2], [122], [47]).

Processes involved in the production of forest reproductive material (FRM, such as seed processing and nursery production) can change the composition and the ratio among individual families in seed lots, seedling stock and in the planted forest at the end. Large changes leads to reduction of GD and unpredictable genetic gain in breeding programs ([133]). The risk of reduction of diversity during production of FRM can be as large as the risk during transfer between seed zones ([17]). All processes relating to the production of FRM for artificial reforestation, as well as their interactions, must be well understood in order to maximize genetic gain and maintain GD ([26]).

There is little evidence that artificial forest regeneration leads to a reduction of GD at the stand level, regardless the seedlings were originated from natural stands, seed stands or seed orchards ([72]). Maintaining GD during reforestation/afforestation increases the chance of natural regeneration of new forest ([78]). Restored populations can be used as future sources of FRM if are properly designed ([141]).

Transfer of FRM during afforestation/reforestation has a great influence on GD by changing gene frequency or introducing genes where they were not present before. The traditional “free movement of germplasm” in Central Europe is a complicating factor when discussing GD ([72], [74]), resulting in a large number of plantations with untraceable origin. Transfer of native species for forest regeneration represent the “experiments in progress” ([49]) and should be monitored, from known origin of FRM to field success and adaptation to changing environment.

This paper provides an overview on relation between GD and FRM in a holistic way: from source selection, transfer of FRM, seed processing and seedling production to reforestation/afforestation.

Levels of genetic diversity

Genetic diversity can be considered at different hierarchical levels: species, provenance (population), family and individual level. GD at lower hierarchical levels depends on factors that prevent panmixia or completely random mating between all individuals ([13]).

Species level

Maintenance of interspecific diversity in afforestation reduces establishment risks, increases biodiversity and the ability of natural regeneration; the value of forest products can be increased or decreased but it always complicates forest management with different management procedures for different species ([78]). Therefore, the artificial restoration and establishment of forests is usually performed with a single species. To maximize profit, the foresters often plant exotic, fast-growing species in monocultures ([6]). Although number of species used for planting is increasing ([19]), the most used species in 2012 at global level were from two genera: Pinus sp. (42%) and Eucalyptus sp. (26% - [50]).

There are potential advantages to be gained by using carefully designed species mixtures in place of monocultures ([64]); in particular, a significant increase in productivity is expected based on projections, as compared with pure stands of the component species ([93]).

Provenance (population) level

Forest tree species are highly heterozygous and contain a high portion of total genetic variation within populations (provenances), while the interpopulation component of variation rarely exceeds 5% ([80], [115], [79]). However, differences between provenances can be detected in seed ([76], [100], [127], [118], [16]), seedlings ([136], [144], [52], [89], [55]), and patterns of spatial distribution can be observed as well ([54]). Variation between populations may be clinal or ecotypic and knowledge on pattern of variation is important in cases of FRM transfer.

Family level

The number of families (half-sib lines) in reforestation determines the degree of GD and adaptibility of the new stand or plantation. This number depends on the seed source (seed stands or orchards), seed processing and nursery production. Since GD can be assessed by the effective population size (Ne - [147]), some forestry authorities use this parameter for the acceptance of FRM. For public reforestation in British Columbia, the minimum Ne recorded for seed lots must be 10 ([137]), thus capturing 95% of the population GD (diversity = 1-1/2Ne - [106], [149]).

Individual level

Genetic diversity within individuals depends on outcrossing and gene dispersal efficiency. In genetically variable tree species it is likely that every seed produced has a different genotype and considerable variation among individuals can be generated in offspring from just only a few parents ([1]). Use of FRM from outcrossing maintains a wide GD, while diversity at individual level is more important in clonal forestry.

A distinction should be made when discussing the number of clones in seed orchards and in clonal forestry ([87]). Therefore, in this section we will address to the number of clones or genotypes in plantations and deal with structure of seed orchards later.

There is no genetic variation within a monoclonal stand, thus diversity must be managed at the estate level ([43]). Combining clones allows resilience to environmental stress and yet still confer benefits of clonal forestry ([44]). The number of clones or genotypes used in the establishment of plantations should balance genetic gain and loss of genetic diversity. This number with level of risk similar to forest established by seedlings, ranges from seven ([82]) to 30 unrelated clones ([83]). More recent researches confirmed these recommendations ([10], [150]). For slow-growing species, a larger number of clones must be used.

How much genetic diversity we need to maintain in the mass production of forest reproductive material?

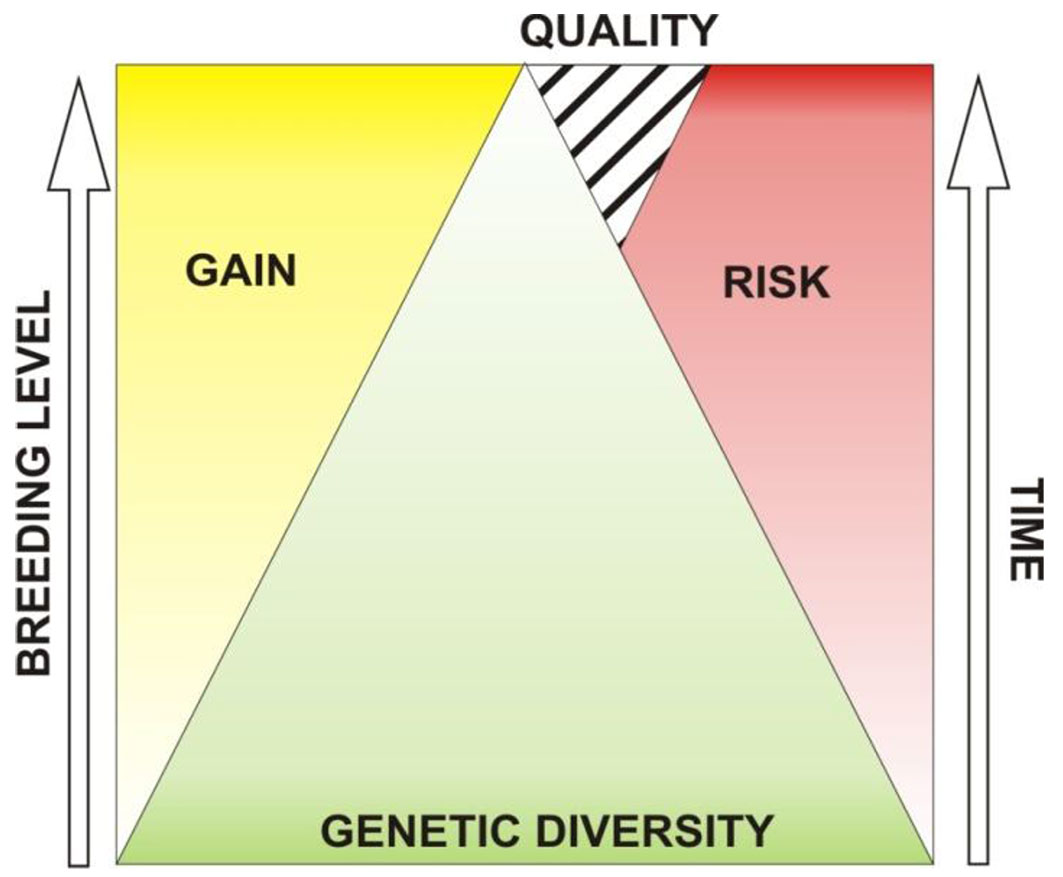

The answer to this question depends on the management objectives, rotation and the breeding level (Fig. 1). Reforestation for conservation purposes most often involves long rotations and requires a wide GD because chances of hazardous situations rise with time (Fig. 1). Long-term trials showed that rare climatic events occurred every 10 or more years and that the prevalent reason of maladaptation was due to seed sources ([59]). Commercial plantations have shorter rotations but narrow GD, as a result of long-term breeding programs, with short rotation coppice as an extreme example.

From the genetic point of view, we can distinguish three ways of artificial establishment of forests, and therefore the mass production of FRM for their needs. These are seedling forestry, family forestry and clonal forestry. In seedling forestry, the number of genotypes in new forests is equal to the number of planted seedlings. In family forestry, the number of genotypes is equal to the number of seedlings from controlled crossing (which is usually small) before vegetative multiplication. In clonal forestry, the number of genotypes is equal to the number of clones used for planting. Obviously, GD must be reduced in order to obtain genetic gain and because of that, it is very important to find the balance between these two objectives (GD and genetic gain) in forestry.

Each subsequent breeding level increases genetic gain but narrows genetic diversity. Increase of risk of failure follows the increase of rotation time. This risk is somewhat lower in case of production and use of good quality FRM.

How mass production of forest reproductive material influence genetic diversity?

Mass production of FRM is based on vegetative or generative reproduction. In this paper, we consider sexual reproduction with distinction between FRM from open and controlled pollination (crossing). Controlled crossing is limited in terms of quantity, and its use is often restricted to breeding programs. A combination of controlled crossing with mixed propagation can be used for the mass production of reproductive material, i.e., vegetative multiplication of young seedlings from full-sib families ([13]). This method of regeneration is called “family forestry” ([110], [102]). However, the most common reproductive material in forestry is produced by open crossing.

There are several methods for the production of improved reproductive material from open pollination. The mostly used are seed production areas (SPA) or seed stands (SS), parts of forest selected from natural stands or old plantations. The next level in tree breeding is seed orchards (SO) of trees without pedigree and, finally, clonal plantations of next generations from tested genotypes. Stands and orchards for the production of seeds from open pollination are suitable for use of the additive genetic variance (or general combining ability - [13]). In this sense, the SO should ensure the improvement of the quality and quantity of seeds, in comparison to the SS ([139]), but it contains a limited number of genotypes. The level of improvement is assumed to rise from SS to clonal SO, but simultaneously a decline in genetic diversity may be expected. However, results of the studies rewieved in the following chapter do not support this assumption.

Seed production

Seed source selection

GD of seed lots is influenced by the size of the parent population, the balance in the parental reproductive success, the kinship of its members, and by the level of inbreeding ([38]). A large variability in fertility is observed between and within populations ([62]), among clones ([27], [8], [107], [32], [81]), and between years ([92]). This variability was greater in the stands than in SO ([62]), in years of low yield ([27]) and in younger populations ([62]). In SO such variability is somewhat larger on the male than on the female side ([62]), opposite to what can be observed in natural population ([9]). Some of the problems related to the effective population size and balance of parents in reproduction, can be solved with supplemental mass pollination ([37], [139]) and assisted pollination ([101]).

There are concerns about the effective number of parents in the SS and SO because only a portion of individuals contributes to the gametes pool and transmits its genes to the next generation ([46], [15], [77]), thereby reducing the effective population size ([30]). However, in plantations established from seed originating (or collected) from SO, there is no risk of further reduction of the effective population size in the next generation, because these plantations should not be used for seed collection ([137]).

Properly managed SS can be used as a source of high quality seeds for reforestation until genetically improved seed from SO becomes available. In most cases, the establishment of new forests with FRM originating from SS provides a level of GD similar to wild population from which they comes ([6]).

SS must consist of one or more groups of trees properly spaced and in sufficient numbers ([112]). Despite open pollination at the family level, there are deviations from the random mating in SS ([65]), which should be considered at seed collection. It is often necessary to perform genetic melioration in SS, which include seed trees selection, thinning and other activities that enhance productivity ([94]). Removing phenotypically inferior trees from SS improves the quality of seeds and seedlings ([129]), but may reduce the GD of the next generation ([90]).

SO represent a link between tree breeding and afforestation ([66], [28], [139]). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) scheme recognizes three types of SO: clonal, family and from material at the provenance level ([112]). The number of clones or genotypes that should be deployed into the SO is very important in terms of productivity and stand health. This number has to ensure the same level of heterozygosity expected in natural populations and greatly depends on the tree species. On the other hand, the genetic gain is increased through the decrease of the number of clones. In Sweden, Finland and Korea the usual number of clones in conifers SO ranges from 70 to 139 ([61]), while in the USA 24 clones (14-36) are usually considered for Pinus taeda L. and 42 (25-55) for Pinus elliottii Engelm ([98]). For the establishment of SO in Finland the minimum number of clones is 30 ([71]) and in Sweden the proposed number is 20 clones ([87]). Concerning the number of clones to include in the establishment of SO, different recommendations are made by a number of authors: more than 20 clones ([58]), no more than 30 ([150]) or 40 ([10]), between 30 to 40 ([120]), more than 40 ([72]). However, not all clones should be represented with an equal number of ramets ([85], [86], [48], [88]).

There is concern about the GD of seed lots from SO, because if a lower heterozygosity results from an increased level of inbreeding, we can expect a reduction of fitness ([11]), which may jeopardize the success of the establishment of new forests. However, the results of the reviewed studies are not conclusive (see Tab. 1). In all the eight studies reviewed here, isozyme markers were used to estimate the level of GD. There are more than one study only for Picea sitchensis and their results are similar.

Tab. 1 - Differences in the parameters of genetic diversity among natural populations (NP) and seed orchards (SO). (A): total number of alleles; (Au): number of alleles observed only in NP or SO; (An): number of alleles per locus; (P): % of polymorphic loci; (He): expected heterozygosity); (*): first generation; (**): second generation; (+): arithmetic mean of replicates reported separately in the original study.

| Species | Type | Heterozygosity Parameters | Markers | Source | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Au | An | P | He | ||||

| Pinus sylvestris L. | NP | 34.7+ | - | - | - | 0.283+ | Isozymes | Muona & Harju ([103]) |

| SO | 39.5+ | - | - | - | 0.266+ | |||

| Thuja plicata Donn ex D.Don | NP | - | - | 1.1 | 11.1 | 0.054 | Isozymes | El-Kassaby ([28]) |

| SO | - | 1 | 1.2 | 11.1 | 0.058 | |||

| Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr. | NP | - | 4 | 2.0 | 69.2 | 0.216 | Isozymes | El-Kassaby ([28]) |

| SO | - | 6 | 2.7 | 84.6 | 0.238 | |||

| NP | - | 3 | 1.82 | 66.9 | - | Isozymes | Chaisurisri & El-Kassaby ([22]) | |

| SO | - | 6 | 2.77 | 100 | - | |||

| Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | NP | - | 4 | 2.14 | 52.6 | 0.171 | Isozymes | El-Kassaby & Ritland ([31]) |

| SO* | - | 2 | 2.28 | 62.5 | 0.172 | |||

| SO** | - | 1 | 2.25 | 56.3 | 0.163 | |||

| Picea glauca x engelmanni | NP | 46 | 7 | 2.7 | 64.7 | 0.210 | Isozymes | Stoehr & El-Kassaby ([138]) |

| SO | 40 | 1 | 2.4 | 64.7 | 0.207 | |||

| Picea glauca (Moench.) Voss. | NP | 39 | 9 | 2.17 | 55.6 | 0.164 | Isozymes | Godt et al. ([40]) |

| SO | 31 | 1 | 1.72 | 50.0 | 0.157 | |||

| Pinus banksiana Lamb. | NP | 55 | 12 | 2.04 | 59.3 | 0.114 | Isozymes | |

| SO | 45 | 2 | 1.67 | 44.4 | 0.114 | |||

The total number of alleles (A) was higher in two SO of Picea sitchensis, compared to their natural populations (NP). In other three studies reporting A, allelic richness is reduced in SO. However, in all studies some alleles which were not observed in NP were recorded in SO.

The number of alleles per locus (An) and the percent of polymorphic loci (P) in SO were equal to natural populations for Thuja plicata and Picea glauca x engelmanni; higher for Picea sitchensis (significantly) and Pseudotsuga menziesii, but lower for Picea glauca and Pinus banksiana.

The percent of polymorphic loci (P) was equal in SO and NP of Thuja plicata and Picea glauca x engelmanni; and higher for Picea sitchensis and Pseudotsuga menziesii. The polymorphism of loci in the SO was lower for Picea glauca and Pinus banksiana.

The expected heterozigosity (He) was higher (not significantly) for Picea sitchensis and similar for other species.

The above results indicate that phenotypic selection at the early stage of breeding of highly polymorphic species does not significantly reduce genetic variability, likely due to the sampling of trees for plantation establishment from widely distributed natural populations ([31]). These results are confirmed in more recent study for Picea glauca ([105]), where single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were used to assess the potential impact of artificial selection for height growth on the genetic diversity. The comparison of same-size control populations with different family selection intensities did not result in notable differences in standard genetic diversity estimates.

Seed collection

Seed collection is the critical stage in mass production of FRM for maintaining of GD. A large portion of the original GD in seed sources can be lost when seeds are collected from a small number and/or from inappropriate trees.

Two methods of collecting seeds are commonly applied ([111]). The first method involves the collection at SS level, not taking into account the parents’ participation in seed lots. The second method is based on the collection of the same amount of seeds from each maternal plant (unit of collection), thereby better preserving GD. However, during collection, seeds are usually bulked in a seed lot at population or family level. In this regard, a seed lot represents the bulk of all parents that participate in seed production, though not all parents are equally represented. Once seeds of individual families (mother trees) are mixed, control over the participation of individual families to the seed lot is lost.

A uniform harvesting across the whole collecting area is recommended ([67]). The number of mother trees depends on the overall size of the area covered by seed collection, but the recommendations for this number vary depending on the source. The loss of genetic diversity in the next generation is inversely proportional to the number of sampled parents ([7]); therefore, a smaller amount of seeds collected from many parent trees is more effective on GD maintenance than the opposite. For most purposes it is recommended to collect the same amount of seeds from at least 20 ([113]) or 50 distant mother trees, so that each seed tree contributes with approximately 4% or 2%, respectively, to the seed lot. In case of seed collection from 50 trees, the expected reduction in heterozygosity is 1% ([95]). However, it is safe to accept the recommendation that seed should not be collected from less than 40 trees, except in some cases ([111]). This number can be lower in natural distributed species or in pioneer species, and higher in dioecius species ([95]). Generally accepted rules have been developed for how many samples one should collect to capture at least 95% of genetic variation (measured as alleles) with the least effort ([141]).

Mother (seed) trees should be carefully selected during collection and this is usually done by phenotypic selection. Phenotypic selection successfully conserves genetic variation in natural populations and presents an easy and inexpensive way to provide material for further breeding ([28]).

Despite a sufficient number of properly selected seed trees is chosen for collection, the family ratio in the seed lot may be uneven. Number of viable seeds from different families may differ because of the unequal number of collected seeds, fruits or cones, different number of seeds in the fruits or cones and different viability due to the state of maturity, insect attacks, infections and maturation ([124]).

Collecting seeds in non-mast years leads to a reduction of genetic diversity, as seeds from a small number of parents are included which generally are not representative of the population. Due to the large variation in the genetic structure of seed crops between years ([109], [75], [108]), diversity can be preserved by mixing seeds collected in different years ([63]). Moreover, collecting seeds from trees of different age groups mimic natural regeneration and increases adaptive potential. However, cutting the youngest trees to implement a seed tree regeneration method leads to a reduction in the frequency of certain alleles; for this reason, collecting seeds from trees of different ages may preserve rare alleles to the next generation ([2]). Care should be taken to avoid unintentional selection of traits during seed harvest (e.g., systematically discarding small seed), and growth rate, timing of flowering and fruiting and harvesting time window should be also considered ([141]).

Seed processing

Seed processing can lead to a decrease in GD by reducing the participation (or even the elimination) of some families from the initial seed lot. Most methods of seed processing are custom to average sized seed. Indeed, seeds closer to the average for any trait subject to processing, are less likely to be accidentally eliminated ([124]). As seeds of different families may differ in size, weight, morphological and physiological characteristics, some families may be preferentially subject to selective pressures and can be eventually discarded from the final seed lot. Equal representation of all families in the seed lot is not possible in practice, unless each family is processed separately ([26], [124]). Systematic elimination (directional selection) carries a higher risk for the reduction of GD in the seed lot, as certain types of seeds are discarded based on physiological and especially the physical properties of seeds, which are under strong genetic control of mother trees.

Unlike the systematic, random elimination has less impact on the genetic constitution of seed lot, because the seed probability to be eliminated does not depend on its physical or physiological traits. An example of random elimination is seed storage, when storability of large and small seeds or seeds from different families is the same ([124]).

Seed grading

Seed grading is usually based on seed size and weight, and leads to rejecting a certain amount of small, but still viable seeds. This procedure can change the genetic constitution of the whole seed lot, discarding entire families with smaller seed size. However, even in the absence of seed grading a similar effect may occur, as the plants developed from small seeds are smaller and show a higher mortality rate ([17]).

The size and weight of seeds are under strong parental genetic control ([5], [18], [128]). In addition, seed size and weight also differ in relation to maturity ([17]), position of reproductive structures, external conditions and year ([34]). As a consequence, grading based on seed size and weight entails at the same time a selection of other characteristics related to these.

The size and weight of seeds are positively associated with viability and germination parameters ([23], [128]). There is also a strong positive relationship with seedling attributes such as size and survival ([133], [23], [41]), but it weakens with time ([18]). However, although large seeds can provide rapid and successful germination and early seedlings growth, this is not necessarily related to the embryos genetic potential for growth ([124]). Indeed, some results suggest that seed size is under moderate genetic control (i.e., seed size has a lesser impact on seedling attributes), while germination parameters are under strong genetic control ([20], [5]). Lack of seed effect on seedling attributes was also observed ([21]). Therefore, what is obtained in terms of physiological quality by selecting only the most viable seeds may be lost in terms of genetic quality and diversity ([124]). For this reason, Edwards & El-Kassaby ([26]) recommend mixing of sound and viable seeds from all size classes before storage or sowing.

Seed storage and pre-sowing treatment

Seed storability is under strong genotype influence and the preservation of viability during storage largely differs among families ([124]). In this case, the risk of narrowing GD lies in the possibility that seeds with a relatively low vigor completely lose their viability over a long-storage period. In addition, seed dormancy has a strong genetic basis; therefore, seeds from different families may differently react to the pre-sowing treatments, and viable seeds can remain dormant during the germination period. However, seed treatment and stratification has been reported to have only minimal effects on the genetic structure of reproductive material ([67]).

Germination

Seed germination may strongly decrease GD of seed lots due to different germination capacity, speed and vigor among families and individual seeds, and may lead to either under- or overestimation of the effective population size of seed lots ([38]). In fact, the lack of germination of an individual family is actually positive as long as it is the result of genetic control, because a family of low genetic potential is eliminated from the nursery stock. However, if the absence of germination is due to seed processing, families with high genetic potential will not transfer genes into nursery stock, thereby changing the effective population size. The speed and vigor are important features because, in favorable nursery conditions, seedlings are immediately able to capture the available resources.

Seed germination parameters are under strong genetic control both in gymnosperm ([29], [24], [18]) and angiosperm ([142], [5]). This control is particularly pronounced in gymnosperm ([124]), and can be explained by the maternal contribution which is dominant over the paternal ([26]). However, it is very difficult to distinguish the genetic influence on germination from the influence of seed processing, in particular storage and dormancy.

Seed germination is an important parameter for seedlings production. This is well explained by Campbell & Sorensen ([17]): “In species with low germination capacity most of the loss occurs before germination, but in species with high germination capacity, the losses are associated with the rejection of the seedlings at the end of production. When the germination is weak, growing density in seedbed is low and most of the seedling exceed standard for rejection; when the seed germinates well, the density is high and larger number of seedlings does not satisfy standard criteria”.

Seedling production

A high GD included in seed lots after collection may be contrasting with the uniformity desired for mass production of seedlings in the nursery. Indeed, seeds with uniform germination and seedlings with consistent growth are easier to be cultivated in the nursery. In addition, nursery operations are more effective when carried out in a homogenous environment.

A significant reduction in GD may take place in the nursery, depending on nursery conditions and production methods. Production of seedlings under environmental conditions much different from those at the seed collection site may cause directional selection at this stage or after planting ([17]). Furthermore, it is often assumed that seedlings should be raised under climatic conditions similar to those at the future planting site, to avoid selective effects, but even if this seems optimal, it is not realistic ([67]).

Distinction should be made between production of bareroot and containerized seedlings. Risk of reduction in GD by directional selection is lower in production of bareroot seedlings with sowing seeds in the beds. However, selection pressure is stronger in bareroot nurseries compared to container nurseries, due to harsher field conditions during germination. Uniformity of growing conditions is a keystone for commercial nursery production. There are evidences that temporarily heterogeneous environmental conditions might promote a higher survival of heterozygote genotypes, while homozygosity could be favored in relatively homogeneous conditions ([36]). However, the majority of the study did not confirm any reduced heterozygosity of seedlings grown under optimal, homogeneous environmental conditions (Tab. 2).

Tab. 2 - Differences in the parameters of genetic diversity between the seed lot (SL) and the seedling stock (SS). (A): total number of alleles; (An): number of alleles per locus; (P): % of polymorphic loci; (He): expected heterozygosity; (Ho): observed heterozygosity); (U): unmanaged; (NR): natural regeneration; (SOS): seed origin stand; (SO): seed orchard.

| Species | Type | Heterozygosity Parameters | Markers | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | An | P | He | ||||

| Pinus contorta var. latifolia | U1 | - | - | - | 0.44 | RAPD | Thomas et al. ([140]) |

| NR2 | - | - | - | 0.39 | |||

| SS | - | - | - | 0.43 | |||

| Picea glauca x engelmanni | SL | 38 | 2.2 | 70.6 | 0.219 | Isozymes | Stoehr & El-Kassaby ([138]) |

| SS | 39 | 2.3 | 64.7 | 0.215 | |||

| Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii | NR | - | - | 87 | 0.190 | Isozymes | Adams et al. ([2]) |

| SS | - | - | 95.5 | 0.203 | |||

| Quercus ilex L. | SOS3 | 10 | 8.79 | - | 0.653 | Microsatellites | Burgarella et al. ([15]) |

| SS | 7 | 6.98 | - | 0.641 | - | ||

| Quercus robur L. | SO4 | - | - | - | 0.29 | Isozymes | Borovics et al. ([12]) |

| SS | - | - | - | 0.28 | |||

| SO | - | - | - | 0.75 | Microsatellites | ||

| SS | - | - | - | 0.72 | |||

The production of containerized seedlings may also lead to a possible reduction of GD in the seedling stock. Indeed, more than one seeds are usually sown per cell and smaller seedlings are removed after germination. This results in an undesired directional selection favoring parents with less dormant and fast-germinating seeds, though their seedlings do not necessarily show better performances in the field. To this purpose, Edwards & El-Kassaby ([26]) recommend to sow one seed per cell or sowing of separated families, not the whole seed lots. Difference in seedling size among families has been well documented ([96], [56], [146], [25]). However, differences in family composition between the initial seed lot and the final seedling stock are often not large enough to justify the increased costs of producing seedlings from different families separately ([133]).

Based on the literature examined, there are no evidences that nursery operations might reduce GD. In five reviewed studies, seedling stocks did not show significant differences in GD parameters as compared to their relative seed lots (Tab. 2). In addition, seedling stocks of Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii used for artificial regeneration had a significantly higher level of GD compared to natural regeneration ([2]). Similar results have been reported for seedling stocks of Pinus contorta var. latifolia, with GD parameters similar to those of unmanaged stands, but higher compared to natural regeneration ([140]). Furthermore, no reduction of GD through seedling production was observed in Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco ([133], [69]) and Fagus sylvatica L. ([68]). In these studies, the similar GD found in the seedling stock as compared with the original population has been attributed to the favorable conditions of growth in the nursery, making the selection pressure in the nursery weaker than in nature. Contrastingly, significantly lower values of the GD parameters in the seedling stock compared to the parent seed stand have been reported only for Quercus ilex L. ([15]). The authors attributed this evidence to an inappropriate seed collection, which was limited to a small number of spatially close trees.

Finally, the reviewed studies also suggested that seedling production in the nursery maintains the GD observed in the initial seed lot, regardless to species and production method (bareroot - [133], [68]; or container - [68]).

Culling

Grading and culling of seedlings is a routine procedure in nursery as integral part of lifting and packaging. Culling is usually based on height, diameter and physical damage. Culling based on physical damage does not represent a directional selection (the damage often occur by chance), while culling based on size can be directional, depending on the genetic control of height and diameter ([17]). Genetic control of multiple traits related to to seedlings development has been reported ([148]), though many non-genetic factors may affect seedling size.

Culling based on height and diameter partially discards inbred plants and other poor or abnormal genotypes, thus increasing the adaptability and growth capacity of the seedling stock. Such procedure does not constitute a directional selection, as inbred seedlings are usually inferior, susceptible to disease and often can not survive under field conditions. However, removing smaller plants from seedling stock can discard genotypes with possible faster growth at later stages. There are numerous examples that smaller seedlings in the nursery achieve a faster growth in the field ([119], [143], [60]). Careless selection of fast-growth families may represent the most important factor affecting GD ([24]).

In this context, standards for seedlings culling should be determined by seed origin (seed stands, seed orchards and full-sib crossing) and nursery conditions ([97]). In order to prevent further narrowing of GD, cultivation of all plants is recommended, including those that would be discarded based on the size. These can be grown one additional year in the nursery and used for planting on the same site ([60]).

Reforestation (artificial regeneration)

Reforestation activities largely depend on the goals, with distinction between forest regeneration and tree plantations. These goals must be a compromise between productive and non-productive (benefit) functions (e.g., biodiversity, landscape, environmental protection). Artificial regeneration of forests should replace the felled stand with a new, well-stocked and better quality stand ([130]), while in general tree plantations are defined as planted forests of commercially important species ([84]).

Artificial regeneration is the most obvious silvicultural practice resulting in possibly drastic changes of genetic structures not only in the planted stands, but also in the neighboring forests via gene flow ([36]). The genetic structure and variation of artificially established forest stands may be conditioned at the species (monocultures or species mixtures) and individual (monoclonal or polyclonal) levels, depending on the initial seed lot and the seedling stock. Since GD of tree plantations was previously discussed, here we will deal with reforestation and artificial regeneration of forests only.

Distinction should be made between the establishment of new forests by direct sowing and planting of seedlings. From the genetic point of view, reforestation by direct sowing has a lower impact on GD as compared with planting seedlings ([95]). On the other hand, seedlings are by far the most used type of FRM in artificial regeneration.

Based on the literature analyzed in this review, differences between natural (including those from natural regeneration) and planted populations are not conclusive (Tab. 3). Seven out of 13 reviewed studies reported reduction of GD after artificial regeneration and this reduction was significant in three cases: Picea glauca ([116]), Pinus brutia Ten. subsp. brutia ([4]) and Dalbergia sissoo ([114]). The results previously obtained in Picea glauca by RAPD markers ([116]) were reassessed using microsatellites by Fageria & Rajora ([33]); a similar trend of reduction in GD was found, but the differences between progeny from phenotypic selection and natural regeneration were not significant (Tab. 3). The significant decrease of GD parameters from natural stands to plantations observed in Pinus brutia Ten. subsp. brutia ([4]) should be considered with care, since the small sample size analyzed and the origin of seeds used for plantation (obtained from older plantations, not from SO or natural SS). Pandey et al. ([114]) found no variation at the Gdh-A locus in five plantations, while two to four alleles were found at the same locus in five natural populations. This complete fixation of Gdh-A gene locus in plantations was probably due to inappropriate seed collection (seed origin was unknown) from a small number of trees.

Tab. 3 - Differences in the parameters of genetic diversity between initial population or natural population and new plantations. (A): total number of alleles; (An): number of alleles per locus; (P): % of polymorphic loci; (He): expected heterozygosity; (Ho): observed heterozygosity); (+): Arithmetic mean of replicates separately reported in original study.

| Species | Type | Heterozygosity Parameters | Markers | Source | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | An | P | He | Ho | ||||

| Pinus sylvestris L. | Natural | - | - | - | 0.419 + | 0.359 + | Isozymes | Muona et al. ([104]) |

| Plantation | - | - | - | 0.423 + | 0.408 + | |||

| Initial Krotoszyn | 77 | 3.08 | 92 | 0.254 | 0.254 | Isozymes | Kosinska et al. ([70]) | |

| Plantation Krotoszyn | 78 | 3.12 | 92 | 0.242 | 0.231 | |||

| Initial Gubin | 69 | 2.76 | 80 | 0.257 | 0.256 | |||

| Plantation Gubin 1975 | 74 | 2.96 | 96 | 0.234 | 0.233 | |||

| Plantation Gubin 1982 | 65 | 2.56 | 80 | 0.244 | 0.237 | |||

| Pinus contorta var. latifolia |

Unmanaged | - | - | - | 0.44+ | - | RAPD | Thomas et al. ([140]) |

| Natural regeneration | - | - | - | 0.39+ | - | |||

| Plantation | - | - | - | 0.43+ | - | |||

| Unmanaged | 12.2 | - | - | 0.73 + | 0.46 + | SSR | ||

| Natural regeneration | 11.5 | - | - | 0.72 + | 0.47 + | |||

| Plantation | 11.5 | - | - | 0.74 + | 0.46 + | |||

| Natural regeneration | - | 1.83 | 32.6 | 0.160 | 0.137 | Isozymes | Macdonald et al. ([91]) | |

| Plantation | - | 1.83 | 35 | 0.149 | 0.138 | |||

| Pinus brutia Ten. subsp. brutia |

Natural | - | - | 83.7 | 0.248 | - | RAPD | Al-Hawija et al. ([4]) |

| Plantation | - | - | 78.7 | 0.234 | - | |||

| Pinus roxburghii Sarg. | Natural | - | 5 | - | 0.52 | 0.5 | Microsatellites | Gauli et al. ([39]) |

| Plantation | - | 4.93 | - | 0.52 | 0.5 | |||

| Picea glauca (Moench) Voss | Old natural | - | 1.89 | 88.7 | - | 0.381 | RAPD | [116] |

| Natural regeneration | - | 1.84 | 83.8 | - | 0.349 | |||

| Plantation | - | 1.72 | 72.2 | - | 0.297 | |||

| Progeny from phenotipic selection | - | 1.67 | 66.5 | - | 0.259 | |||

| Natural old | 109 | 10.9 | - | 0.637 | 0.492 | Microsatellites | Fageria & Rajora ([33]) | |

| Natural regeneration | 108 | 10.8 | - | 0.643 | 0.500 | |||

| Plantation | 102 | 10.1 | - | 0.632 | 0.479 | |||

| Progeny from phenotipic selection | 100 | 10 | - | 0.634 | 0.788 | |||

| Picea abies | Initial | - | 3 | - | 0.169 | 0.183 | Isozymes | Pacalaj et al. ([113]) |

| Progeny from 10 | - | 2.95 | - | 0.190 | 0.189 | |||

| Progeny from 20 | - | 2.95 | - | 0.182 | 0.182 | |||

| Progeny from 30 | - | 3 | - | 0.181 | 0.184 | |||

| Progeny from 40 | - | 2.91 | - | 0.183 | 0.182 | |||

| Picea mariana | Natural regeneration | - | 2.56 | 77.3 | 0.320 | 0.237 | Isozymes | Rajora & Pluhar ([117]) |

| Artificial regeneration | - | 2.51 | 72.7 | 0.315 | 0.230 | |||

| Cupressus sempervirens L. var. horizontalis |

Natural | - | - | 77.8 | 0.244 | - | RAPD | Al-Hawija et al. ([4]) |

| Plantation | - | - | 79.3 | 0.241 | - | |||

| Quercus ilex L. | - | - | - | - | - | - | Microsatellites | Burgarella et al. ([15]) |

| Plantation | 6 | 5.97 | - | 0.518 | - | |||

| Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze | Nonmanaged | - | - | 82.0 | - | 0.26 | RAPD | Medri et al. ([99]) |

| Managed | - | - | 72.5 | - | 0.26 | |||

| Progeny | - | - | 59.7 | - | 0.22 | |||

| Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. | Natural | 3 + | - | - | 0.255 | - | Isozymes | Pandey et al. ([114]) |

| Plantation | 1 | - | - | 0 | - | |||

The above results suggest no significant negative impact of artificial regeneration per se on GD. Nonetheless, this impact is clearly influenced by the type of FRM and the level of GD captured in FRM.

Transfer of forest reproductive material

Although the transfer of FRM is not directly related to its production, knowledge of the future use can provide important guidance for mass production. The success of reforestation in the case of transfer of reproductive material is directly dependent on the ability of a population to adapt to the new environmental conditions. Previous work has mainly focused on pairing provenances or genotypes with sites where they adapted well and where they can be well recovered. Transfer of reproductive material should be based on knowledge on planting site, species genetic diversity and biology ([53]). Transfer of reproductive materials contributes to gene flow, introducing new genes into local gene pools or changing the local frequencies of genes already existing in the local pool ([1]). Uncontrolled transfer and the use of FRM of unknown origin pose threats to the adaptation and/or the adaptive potential of tree plantations, and its consequences are not necessarily restricted to plantations ([36]).

Provenance tests show that transferred populations often perform as well as the local provenances or better ([52], [73]). Provenances from warmer climate grow faster than the local populations, as long as they are not transferred to a much different climate ([126]). This may be due to the fact that plants from warmer climate grow longer in the fall than in colder climates ([57]) and this growth pattern is maintained in the new conditions. However, favorable growth environments for specific provenances or populations are currently changing due to climate change, bringing the need of redefining the concept of local gene pool and seed zones ([14]). Forest tree populations planted today must face climate challenges during this century ([145]). In this context, there are three possible outcomes for forest tree populations in a rapidly changing environment: persistence through migration, persistence through adaptation in current locations and extirpation ([3]).

There is concern that local natural adaptation and migration of plants can not keep up pace with climate change. However, evolution of trees can take place in just a few generations or less than 200 years and, in some cases, even only one generation is needed for local adaptation ([131], [74], [132]). Adaptation of trees can be supported by appropriate transfer of FRM, taking into account the seasonal adaptation ([121]). Efficient implementation of assisted migration depends on clear guidelines for the transfer of reproductive material in light of climate change ([42]). Populations expected to adapt to future climates are located lower in elevation and further south ([135]); they should be mixed with local populations to favor adaptation to new conditions ([134]). Transfer of FRM northward and/or to colder environment results, to some extent, in the maximum gain in height over local sources ([125]). However, transfer of FRM northward or at higher elevation increases the risk of failure due to sudden stress events. In this sense, nurserymen should collaborate with geneticists to identify genotypes resistant to extreme temperatures and water stress ([145]).

Beside the choice of the best suited FRM (in terms of origin, type, quality, planting site and goal-specific management), tracking the identity of the transferred material is necessary. Unfortunately, at the operational level, application of this theoretical model is often limited by the FRM available on the market. FRM producers (including seed collectors, seed processing stations, nurseries) tend to minimize the number of species, due to economic and management reasons. This emphasizes the need of a project specific planning period of at least five years to allow the production of appropriate FRM for the majority of species, from seed source selection based on transfer guidelines, to seedling production and planting. Additional attention should be payed in situations when a large amount of FRM is needed in short time, after the occurrence of catastrophic events (forest fire, wind or frost damage on large areas).

Conclusion

High genetic diversity is essential for the long-term survival of forests, providing the basis for future adaptation and resistance to stress and changing environment. A high degree of GD is also needed in the case of FRM transfer to long distances or different climates to ensure local adaptation of the transferred material.

Many steps in the mass production of FRM may potentially lead to a reduction of GD in seedling stocks. Phenotype selection, transfer of FRM and breeding, are selective practices that favor specific genotypes. Seed processing and storage, as well as nursery conditions and operations, can also favor certain families and discard others. Furthermore, grading of seed and seedlings can result in unwanted directional selection of the FRM. However, based on the litarure analyzed in this review, no consistent decrease of genetic diversity has been observed during forest reproductive material production and planting.

The adoption of appropriate collection strategies can maximize the genetic diversity in seed lots, aimed to avoid population genetic bottlenecks and maintain the largest effective population size. Collecting seeds from trees of different ages, as well as the mixing of seeds collected in different years, may contribute to maintain GD. Mixing of various classes of seeds before sowing is recommended in cases of afforestation for conservation purposes. Seed collection, processing and seedling production at family level, followed by mixing of seed/seedling families before their use is the safest way to preserve genetic diversity, though this complicates production practices and unduly increases their costs.

Nursery procedures aimed at providing the greatest number of plants per unit of seed, the highest percentage of acceptable trees and the maximum survival of outplanted seedlings, may reduce the risk of narrowing GD. Selection pressure on seedlings tends to reduce when growing conditions are favorable, so that weaker genotypes, non-competitive in natural conditions, can develop into high-quality seedlings. Regarding seedlings production, culling undersized seedlings has the greatest impact in terms of reduction in GD of the FRM. Standards for culling, especially based on height, should be adjusted by taking into account lower hierarchical levels of GD (provenance, population) and the final use of seedlings. Nursery production practices should provide a uniform planting material, with minimal need for culling.

Reforestation success relies on large local diversity, with a choice of appropriate species and proper transfer of FRM. The genetic diversity of the planting material is the result of previous operations carried out during its production. In this context, sowing seeds instead of planting seedlings reduces the risks of loss of GD as the result of directional selection during seed processing and seedling production. However, planting of seedlings is recommended, because it ensures a higher survival rate and a greater chance of success. High survival and high-density planting in reforestation programs promote natural selection in the new population.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Jovana Devetaković

Marina Nonić

Dragica Stanković

Mirjana Šijačić-Nikolić

Faculty of Forestry University of Belgrade, Kneza Višeslava 1, 11030 Belgrade (Serbia)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Ivetić V, Devetaković J, Nonić M, Stanković D, Šijačić-Nikolić M (2016). Genetic diversity and forest reproductive material - from seed source selection to planting. iForest 9: 801-812. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1577-009

Academic Editor

Marco Borghetti

Paper history

Received: Jan 28, 2015

Accepted: Feb 09, 2016

First online: Jun 13, 2016

Publication Date: Oct 13, 2016

Publication Time: 4.17 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2016

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 62513

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 48975

Abstract Page Views: 6477

PDF Downloads: 5637

Citation/Reference Downloads: 67

XML Downloads: 1357

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 3550

Overall contacts: 62513

Avg. contacts per week: 123.27

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2016): 62

Average cites per year: 6.20

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Seedling emergence capacity and morphological traits are under strong genetic control in the resin tree Pinus oocarpa

vol. 17, pp. 245-251 (online: 16 August 2024)

Research Articles

Genetic diversity of core vs. peripheral Norway spruce native populations at a local scale in Slovenia

vol. 11, pp. 104-110 (online: 31 January 2018)

Research Articles

Delineation of seed collection zones based on environmental and genetic characteristics for Quercus suber L. in Sardinia, Italy

vol. 11, pp. 651-659 (online: 04 October 2018)

Research Articles

Patterns of genetic variation in bud flushing of Abies alba populations

vol. 11, pp. 284-290 (online: 13 April 2018)

Research Articles

Genetic variation and heritability estimates of Ulmus minor and Ulmus pumila hybrids for budburst, growth and tolerance to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi

vol. 8, pp. 422-430 (online: 15 December 2014)

Research Articles

Preliminary study on genetic variation of growth traits and wood properties and superior clones selection of Populus ussuriensis Kom.

vol. 12, pp. 459-466 (online: 29 September 2019)

Research Articles

Age trends in genetic parameters for growth and quality traits in Abies alba

vol. 9, pp. 954-959 (online: 07 July 2016)

Research Articles

Clonal structure and high genetic diversity at peripheral populations of Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz.

vol. 9, pp. 892-900 (online: 29 May 2016)

Research Articles

Comparison of genetic parameters between optimal and marginal populations of oriental sweet gum on adaptive traits

vol. 11, pp. 510-516 (online: 18 July 2018)

Research Articles

Genetic variation of Fraxinus excelsior half-sib families in response to ash dieback disease following simulated spring frost and summer drought treatments

vol. 9, pp. 12-22 (online: 08 September 2015)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword