Effects of soil compaction on seedling morphology, growth, and architecture of chestnut-leaved oak (Quercus castaneifolia)

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 10, Issue 1, Pages 145-153 (2016)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1724-009

Published: Jun 13, 2016 - Copyright © 2016 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Soil compaction following traffic by heavy-timber harvesting machinery usually causes an increase in soil strength, that is a stress factor negatively affecting the growth of newly germinated seedlings. This study used a soil strength experiment carried out in a greenhouse to test the hypotheses that increasing soil strength would adversely affect seedling morphology and alter seedling architecture by changing biomass allocation patterns. We explored the effects of soil compaction in a loam to clay-loam textured soil with optimal conditions of water on a continuous scale (0.2-1.0 MPa penetration resistance) on growth responses of the deciduous Quercus castaneifolia (C.A.Mey). Both above- and below-ground seedling characteristics, including size and biomass, were negatively affected by soil compaction. At the highest intensity of compaction, size and growth were reduced by 50% compared to controls; negative effects were typically more severe on below-ground (i.e., the length and biomass of the root system) than on above-ground responses. Increasing soil strength did not change above- and below-ground biomass allocation patterns (i.e., root mass ratio, root:shoot ratio, specific root length), resulting in unchanged seedling architecture. Strong adverse effects were already evident in the low-intensity compaction treatment and no critical soil strength threshold was observed. We conclude that root and height growth in Q. castaneifolia seedlings is limited by any increase of soil strength, though no evidence for the disruption of a functional equilibrium between above- and below-ground plant portions was found up to soil strengths of 1.0 MPa, at least under optimal water supply.

Keywords

Hyrcanian Forest, Penetration Resistance, Growth, Chestnut-leaved Oak, Relative Growth Rate.

Introduction

Soil disturbance and compaction following forest harvesting operations and traffic of skidding machinery can lead to decreases in long-term site productivity and serious forest regeneration problems ([27]). When soil is subjected to a mechanical load, the resulting physical rearrangement brings soil particles closer together, compacting soil and increasing bulk density ([24]). Soil compaction reduces macropores and total porosity ([22]), infiltration capacity and permeability to water ([28]), plant nutrient availability ([12]), gaseous exchange and soil aeration ([28]), and saturated hydraulic conductivity ([24]). Increased soil compaction is associated with a greater proportion of micropores ([17]) and increased soil strength (i.e., increased resistance of soil particles to displacement or soil penetration resistance) for all but soils of low bearing capacity ([28], [4]).

Plants typically exhibit a wide range of responses to increased soil strength, i.e., physiological adaptations that affect morphogenesis, architecture, and nutrient and water use ([33], [35], [6]). Shortly after soil strength increases, the elongation rate of primary and lateral roots decreases, the root cap generally becomes more rounded, and the root diameter behind the meristem (root tip) increases ([18]). As a consequence, morphological traits of roots can change: main roots become shorter and more lateral branch roots are formed, the proportions of fine roots and root xylem vessels are reduced, volume and weight of the root system decrease, and rooting depths become more shallow ([14], [37], [33], [7], [3]). A smaller root system and more shallow rooting depths result in lower amounts of uptake of major nutrients and water, lower rates of transpiration and photosynthesis, and higher leaf water deficits ([33]). Mechanical forces on roots trigger a signaling cascade throughout the plant, resulting in direct physiological effects on leaves and stomata, such as reduced leaf expansive growth and reduced stomatal conductance ([35]). Thus, increased soil strength can heighten plant stress ([33]), reduce overall plant seedling growth performance (i.e., total plant weight, shoot weight, branch weight, shoot height, and stem diameter - [30], [2], [7]), and ultimately enhance baseline seedling mortality beyond levels from exposure to typical environmental stresses ([1]). Young woody seedlings that need to develop effective roots to obtain water and nutrients or face the risk of reduced survival may be particularly sensitive to adverse effects of increased soil strength on root growth ([37]).

The magnitude of the threshold soil strength that can lead to significant physiological effects has been much debated ([35]). A critical soil strength above which woody plant root elongation is severely restricted is believed to be in the vicinity of 2-2.5 MPa, depending on soil type and species ([15]), but it appears that root growth of woody plants may be restricted with any increase in soil strength ([47]). Restricted root growth does not necessarily translate into a reduction of total plant biomass ([8]), which is affected by soil type and texture ([22]), climate ([25]), light ([7]), water and nutrient availability ([22], [8]), species ([2]), and soil strength ([32], [2]). In fact, total biomass of Quercus pyrenaica Willd. seedlings responded positively to increased soil strength under high, but not low, light conditions ([7]). Similarly, total biomass of several deciduous and evergreen tree species responded positively to increased soil strength up to 0.5 MPa, but not beyond ([2]). Further, the relationship between increasing soil strength and different seedling growth responses may not always be linear and different thresholds of soil strength may exist for different growth responses ([2]).

Root-shoot interactions of woody perennials in response to increased soil strength are complex with respect to plant architecture and growth allocations to above- and below-ground portions of woody plants ([10], [46]). Increased soil strength may change the proportional growth allocation between above- and below-ground portions of seedlings ([14], [6], [2], [3]) and decrease the proportion of roots ([33]). It is unclear, however, whether changes in total plant biomass are consistently associated with changes in growth allocation patterns. If so, then structural traits of stems and roots that change with increased soil strength may not simply distort plant architecture ([2]), but might indeed be seen as indicators of a resource-limited feedback between shoot and root growth serving to achieve a new balance between above- and below-ground portions of trees.

In this study, we quantified the relationship between different intensities of soil compaction and a set of above- and below-ground responses of chestnut-leaved oak (Quercus castaneifolia C.A.Mey) seedlings to test the main hypotheses that increasing soil strength (1) causes morphological (size) changes to above- and below-ground portions of the seedlings, (2) causes decreased growth (biomass) responses of the whole plant and all of the plant’s components (e.g., stem, shoot, leaves, roots), (3) causes differential growth allocation patterns to above- and below-ground portions that result in architectural changes to the seedlings, (4) is not linearly related to all growth response variables, and (5) has to exceed differing thresholds for different response variables before significant responses can be detected.

Materials and methods

Study area

The soil material used in this study area came from a Hyrcanian (Caspian) forest stand in the Namkhaneh District of the Kheyrud forest research station (Iran). The region is characterized by brown soils (cambisols) that are the most abundant soil type and cover 90% of the Hyrcanian region. The specific soil of this study area, which was located at an elevation below 700 m a.s.l., has the following characteristics: semi-calcareous brown soils with a loam to clay-loam texture; A1A2B1BtC profile with an average profile depth of 1.05 m and a maximum depth of 1.6 m ([31]); 20-65% water content; 11% organic matter content; 5.8-6.8 pH (H2O); 14.7 C/N. On lower slopes below 700 m a.s.l., chestnut-leaved oak and common hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.) are mixed with ironwood (Parrotia persica C.A.M.), forming the communities Querco-Carpinetum and Parrotio-Carpinetum that are often characterized by two layers with oak in the upper and hornbeam in the lower story. The upper tree distribution limit depends on geomorphology, climate and soil; at higher altitudes chestnut-leaved oak prefers warm and sunny slopes.

Effects of soil compaction on chestnut-leaved oak seedling growth were studied, because this light-demanding species is one of the most productive, valuable, and precious timber species of the Hyrcanian forests of northern Iran ([49]). Growing in areas with mild climatic conditions and on gentle slopes that provide easy access for harvesting, a many-century long harvest history has greatly reduced the extent and abundance of oaks forests to about 8% of stem numbers and standing volume in the Hyrcanian forests. Natural regeneration of this species has become challenging, due to intensive cattle grazing and ground-based timber skidding that have led to highly compacted soils in oak forests. The degree and extent of mechanization of skidding operations has greatly intensified in the Caspian region over the last decade and there is concern about soil compaction and degradation and lack of oak regeneration, with attending consequences for run-off, soil erosion, and flood risk. Before expensive restoration plantings are being considered to regenerate oak, however, it is important to establish whether, and if so, to what extent soil compaction affects above- and below-ground seedling growth and may thus be implicated in the regeneration difficulties.

Sampling methods and measurements

Loose soil to a depth of 30 cm was collected from the A0 (litter), A1, and A2 horizon and transferred immediately to a temperature-controlled greenhouse in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Tehran in Karaj, Iran. The soil was placed into plastic pots where Q. castaneifolia seeds were sown on 25 December 2013; two weeks later (on 9 January 2014) the first seedlings began to sprout. Q. castaneifolia seedlings were grown with constant irrigation to avoid the possible confounding effects of different soil water regimes ([48]). Water was supplied uniformly on a daily basis using a sprinkler irrigation system (15 minutes of irrigation per day) and greenhouse conditions were controlled to be as similar as possible for all seedlings in terms of light, water, humidity and temperature throughout the entire experiment by shifting the position of the pots in the greenhouse during the growing season. To ensure that only seedlings with similar root sizes were used in the compaction experiment (i.e., to minimize pre-compaction size differences), on 29 February 2014, twenty seedlings of almost identical sizes were selected and transplanted into plastic pots large enough (15 cm diameter × 50 cm height) to avoid possible space limitations for root growth over the course of the experiment ([3]). Five seedlings (pots) were randomly assigned to each compaction treatment that was first imposed on the pot. Due to the unusually comprehensive range of above- and belowground seedling measurements undertaken in this study, relatively few seedlings could be investigated.

Similar to previous research ([2], [7]), we created four treatment intensities of increasing soil compaction. The lowest intensity of compaction (no compaction, control) consisted of simply filling the larger pot with the collected soil material without applying additional soil compaction measures; low, moderate, and high intensities of compaction were achieved by manually applying 3, 5 and 7 blows with a compaction hammer from a height of 20 cm above the soil surface, respectively ([7]). Each seedling was then planted into a small hole of a few centimeters made in the substrate into which the root was placed. The mean initial root length of the seedlings was 9.8 ± 2.7 cm. Soil penetration resistance (SPR) was used in this study as a measure of soil strength/compaction. SPR was quantified by taking measurements every 10 cm along the soil profile in each pot using a hand-held penetrometer; the five values were averaged for each pot. Bulk density was measured by taking one soil sample cores from each pot using a thin-walled steel cylinder of 20 mm length and 28 mm in diameter that was driven into the pot by a hammer-driven device. After extracting the steel cylinder from the pot at the end of the experiment, the soil cores were trimmed flush with the cylinder end. Samples were weighed on the day they were collected and again after drying at 105° C for 24 hours in a drying oven to determine water content and bulk density.

Bulk density was calculated as follows (eqn. 1):

where BD is the bulk density (g cm-3), Ms is the mass of the soil (g), and Vt is the volume of the cylinder (cm3).

Soil porosity (TP) was determined by the following equation (eqn. 2):

where PD is the particle density measured by a Guy-Lussac pycnometer according to the ASTM D854-00 2000 standard and BD is the bulk density (g cm-3). A pycnometer is a device to determine the density of a liquid in reference to an appropriate working fluid, such as water or mercury, using an analytical balance; the device is usually made of glass, with a close-fitting ground glass stopper with a capillary tube through which air bubbles may escape.

Particle density (PD) was determined as (eqn. 3):

where dw is the density of water (g cm-3) at the temperature observed, Ws is the weight of soil sample (oven dry); Wsw is the weight of pycnometer, soil and water; and Ww is the weight of pycnometer and water.

Seedlings were grown in the larger treatment pots for 176 days (starting in late February) and harvested at the end of the first growing season (late August). Each plant was harvested by carefully extracting the plant from the pot, followed by washing the roots in a container of water. Seedling roots were gently dried and root length and fresh weights (biomass) of leaves, stems, and roots of each plant were measured. Dry weights (biomass) were obtained after drying leaves, stems, and roots at 70 °C until a constant weight was reached.

The following response variable means were measured or computed for each seedling: (1) morphological (size) responses [cm]: stem length, stem diameter, leaf length, main root length, main root diameter, lateral root diameter; (2) growth (dry biomass [g]) responses: total biomass, shoot biomass, stem biomass, leaf biomass, total root biomass, main root biomass, lateral root biomass; and (3) architectural responses: lateral/main root length ratio, lateral/main root dry biomass ratio, specific stem length (SSL: ratio of stem length to stem dry biomass), specific root length (SRL: ratio of fine root length to fine root dry biomass), leaf mass ratio (LMR: ratio of leaf dry biomass to total dry biomass), root mass ratio (RMR: the ratio of root dry biomass to total dry biomass), stem mass ratio (SMR: the ratio of stem dry biomass to total dry biomass), root-to-shoot ratio (R/S: ratio of root to shoot dry biomass). Although biomass was measured as fresh and dry, the responses in this study are reported for dry biomass.

The experimental design was a completely randomized design whereby seedlings were randomly assigned to the compaction treatment. We applied general linear modeling (GLM, one-way analysis of variance) to relate seedling growth responses to soil penetration resistance (SPR). Since no departure of the data from a normal distribution was observed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (α = 0.05), standard parametric analyses were carried out. Homogeneity of variance among treatments was verified by Levene’s test (α = 0.01). Post-hoc comparisons of compaction intensity treatment group means were performed using Duncan’s multiple range test with a 95% confidence level. Treatment effects were considered statistically significant when P ≤ 0.05. Because the soil compaction treatments resulted in a continuous range of SPR, we used regression models to enable prediction of the responses at various levels of SPR. Stepwise regression was used to identify whether linear or polynomial (second-order) models would result in the best fit, using P ≤ 0.05 and adjusted R-squared as the metric for inclusion of the higher-order polynomial. All statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS (release 15.0) statistical package.

Results

Compaction and porosity

As designed, compaction treatments significantly increased soil penetration resistance from 0.27 ± 0.03 MPa in the control treatment to 0.84 ± 0.06 MPa in the high intensity compaction treatment (P ≤ 0.001) and bulk density from 1.16 ± 0.14 g cm-3 in the control to 1.51 ± 0.08 g cm-3 in the high intensity treatment (P ≤ 0.001 - Tab. 1). Compaction treatments significantly decreased total porosity from 45.7 ± 1.2% in the control to 30.3 ± 1.4% in the high intensity treatment (P ≤ 0.001).

Tab. 1 - Mean (± standard deviation) of soil compaction indices (i.e., penetration resistance, bulk density, and total porosity) in each of the four levels of compaction treatments investigated in this study.

| Compaction treatment |

Penetration resistance (MPa) |

Bulk density (g cm-3) |

Total porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 1.16 ± 0.14 | 45.7 ± 1.2 |

| Low | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 1.29 ± 0.09 | 40.6 ± 2.1 |

| Moderate | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 1.42 ± 0.11 | 34.2 ± 1.6 |

| High | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 1.51 ± 0.08 | 30.3 ± 1.4 |

Seedling morphology (size)

All of the morphological responses of Q. castaneifolia seedlings decreased significantly with increasing SPR (all P ≤ 0.001 - Tab. 2). Comparing values of the morphological responses in the control treatment to the high intensity compaction treatment revealed reductions of 61% in stem lengths, 58% in stem diameters, 43% in leaf lengths, 56% in main root lengths, 48% in main root diameter, and 72% in lateral root lengths (Tab. 2).

Tab. 2 - Means and standard deviations (in brackets) of variables of seedling morphology (size), growth (biomass), and architecture (allocation ratios) of Q. castaneifolia seedlings grown at different intensities of soil compaction. Different letters in a row indicate significant differences among intensities of soil compaction (P < 0.01) based on Duncan’s multiple range tests.

| Seedling characteristics |

Variable | Compaction intensity (mean + SD) | One-way ANOVA (p-value) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Low | Moderate | High | |||

| Morphology (size) |

Stem length (cm) | 28.1 (6.1) a | 19.7 (1.8) b | 13.6 (3.4) c | 10.9 (1.1) c | < 0.001 |

| Stem diameter (mm) | 24.2 (3.3) a | 17.4 (1.3) b | 11.6 (0.9) c | 10.2 (0.8) c | < 0.001 | |

| Leaf length (cm) | 17.4 (1.9) a | 14.3 (1.8) b | 12.2 (2.1) b | 9.9 (1.7) b | < 0.001 | |

| Main root length (cm) | 29.3 (4.1) a | 19.1 (1.3) b | 14.9 (1.0) c | 12.8 (1.4) c | < 0.001 | |

| Main root diameter (mm) | 18.8 (3.1) a | 14.8 (0.8) b | 10.8 (0.8) c | 9.8 (0.8) c | < 0.001 | |

| Lateral root length (cm) | 52.6 (3.9) a | 34.8 (4.8) b | 25.8 (3.3) c | 14.8 (2.0) d | < 0.001 | |

| Growth (biomass) |

Total dry biomass (g) | 65.9 (5.8) a | 52.5 (3.2) b | 40.4 (1.5) c | 27.0 (2.1) d | < 0.001 |

| Shoot dry biomass (g) | 26.6 (2.4) a | 22.0 (1.3) b | 16.7 (2.3) c | 12.4 (0.9) d | < 0.001 | |

| Stem dry biomass (g) | 15.5 (2.5) a | 13.0 (1.7) b | 11.0 (1.3) b | 7.3 (1.0) c | < 0.001 | |

| Leaf dry biomass (g) | 11.0 (3.2) a | 9.0 (0.6) a | 5.6 (1.1) b | 5.1 (1.1) b | < 0.001 | |

| Main root dry biomass (g) | 39.3 (4.1) a | 30.5 (3.8) b | 23.7 (1.7) c | 14.6 (2.1) d | < 0.001 | |

| Lateral root dry biomass (g) | 15.5 (1.7) a | 11.2 (1.9) b | 10.0 (0.5) b | 5.6 (1.5) c | < 0.001 | |

| Architecture (allocation ratios) |

Lateral / main root length | 1.82 (0.24) a | 1.83 (0.22) a | 1.73 (0.23) a | 1.16 (0.15) b | < 0.001 |

| Lateral / main root dry biomass | 0.66 (0.17) a | 0.57 (0.14) a | 0.73 (0.16) a | 0.60 (0.05) a | 0.304 | |

| Specific stem length (SSL) (cm g-1) | 1.86 (0.63) a | 1.55 (0.33) a | 1.25 (0.34) a | 1.52 (0.24) a | 0.171 | |

| Specific root length (SRL) (cm g-1) | 3.48 (0.60) a | 3.30 (0.51) a | 2.59 (0.39) a | 2.85 (1.12) a | 0.226 | |

| Stem mass ratio (SMR) | 0.24 (0.04) a | 0.25 (0.03) a | 0.27 (0.03) a | 0.27 (0.02) a | 0.281 | |

| Leaf mass ratio (LMR) | 0.17 (0.04) a | 0.17 (0.02) a | 0.14 (0.02) a | 0.19 (0.05) a | 0.191 | |

| Root mass ratio (RMR) | 0.60 (0.02) a | 0.57 (0.05) a | 0.59 (0.05) a | 0.56 (0.06) a | 0.563 | |

| Root-to-shoot ratio (R/S) | 1.48 (0.14) a | 1.37 (0.21) a | 1.46 (0.31) a | 1.22 (0.23) a | 0.286 | |

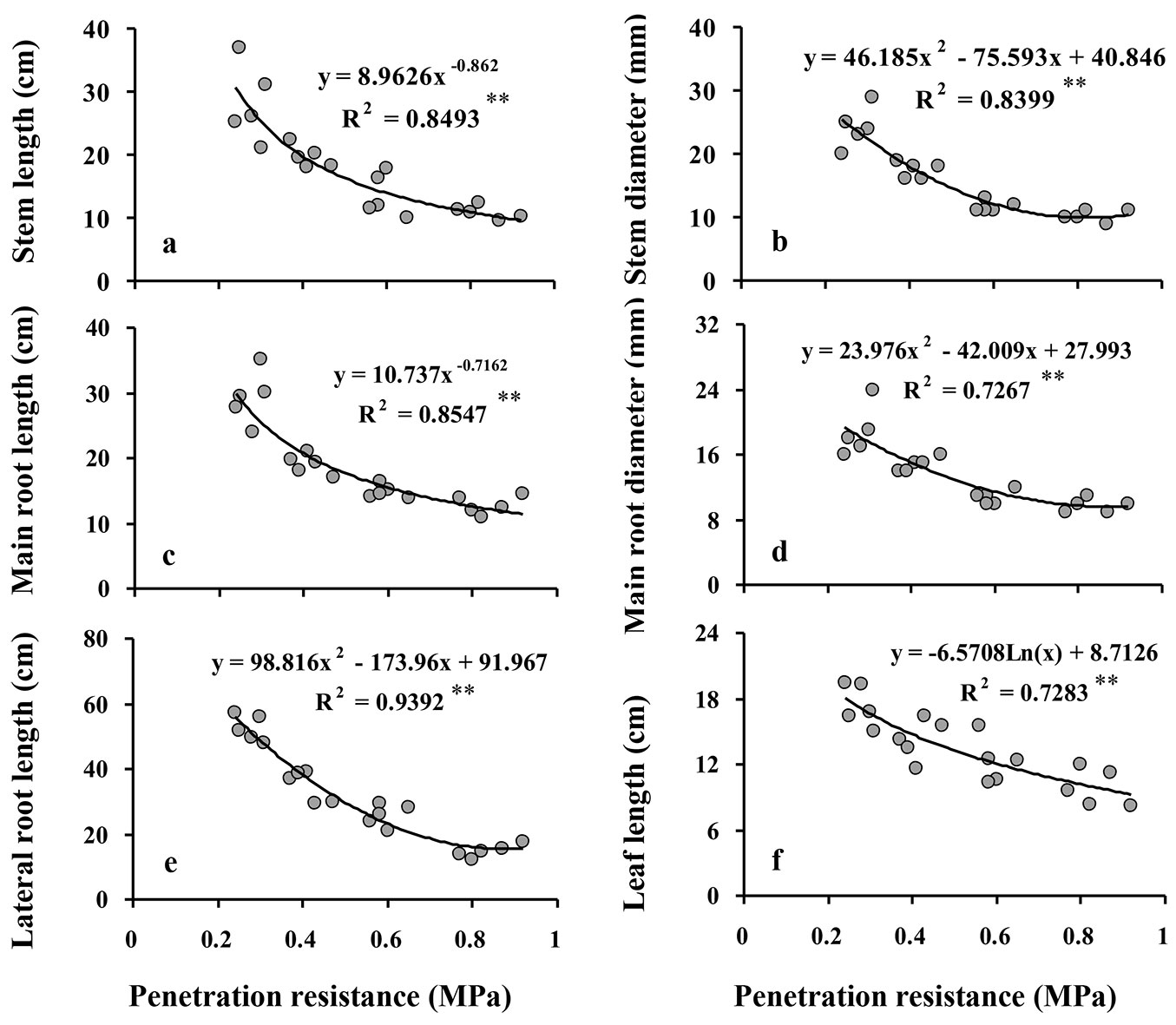

The relationships of the morphological responses to increasing SPR followed negative exponential curves (Fig. 1), indicating that reductions in the responses were greatest between the control and the low intensity compaction treatment and lower with increasing compaction intensity thereafter. This is also seen in the post-hoc comparisons of compaction intensity treatment group means, where Duncan’s multiple range tests detected significant differences in all morphology responses between control, low, and moderate intensity compaction treatments, but did not detect significant differences between the moderate and high intensity compaction treatments in any of the morphological responses except lateral root length (Tab. 2). Further, leaf lengths did not significantly differ among low, moderate, and high intensity compaction treatments (Tab. 2).

Fig. 1 - Relationship between soil penetration resistance (SPR) and morphological responses of Q. castaneifolia seedlings: stem length (a), stem diameter (b), main root length (c), main root diameter (d), lateral root length (e), and leaf length (f). For each graph, the regression equation between responses and SPR and the coefficient of determination (R2) are given. (*): P<0.05; (**): P <0.01; (ns): not significant (P≥0.05).

Seedling growth (biomass)

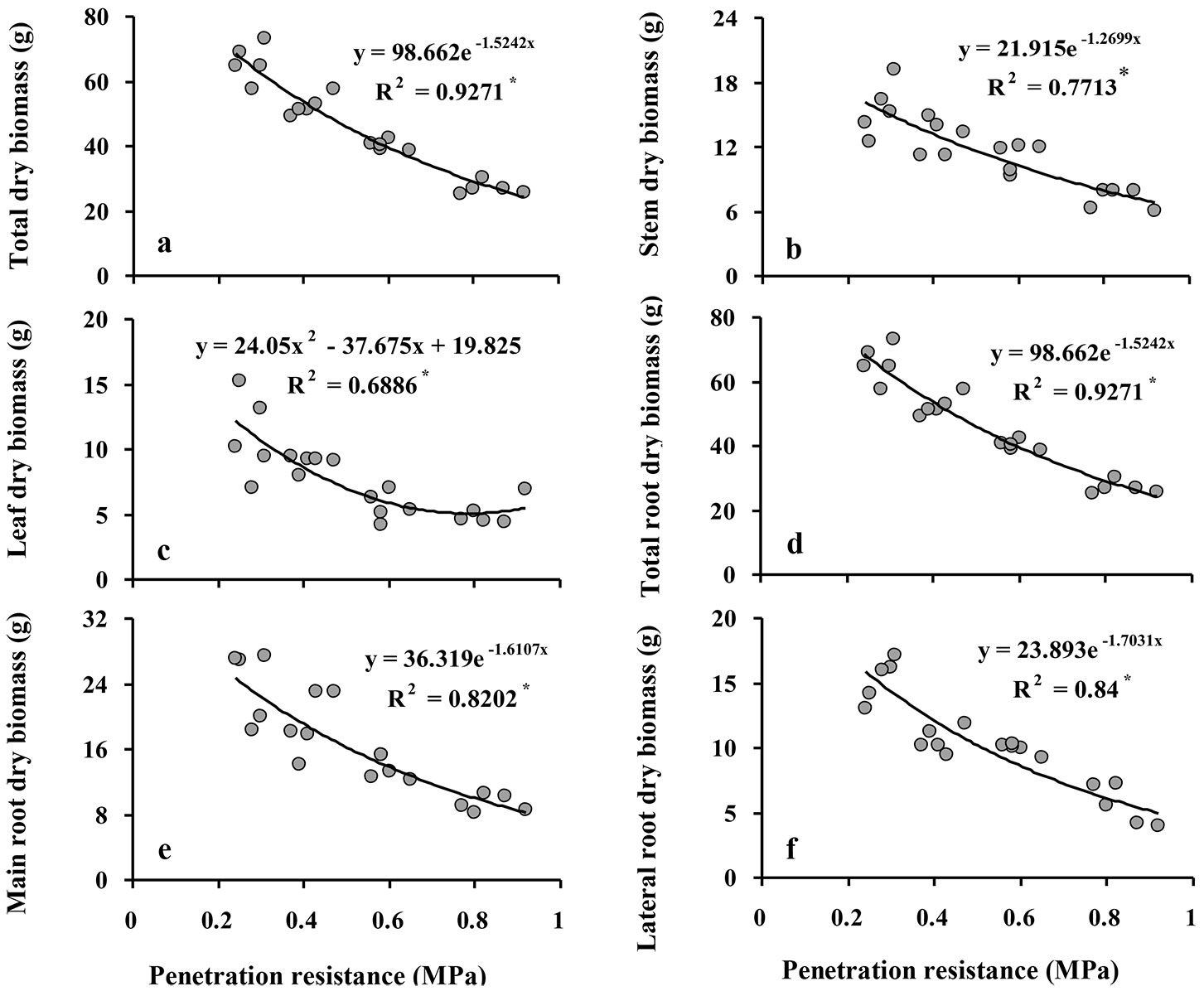

All of the biomass variables of Q. castaneifolia decreased significantly with increasing SPR (all P ≤ 0.001 - Tab. 2). Comparing values of biomass variables in the control treatment to the high intensity compaction treatment revealed reductions of 59% in total biomass, 53% in shoot biomass, 53% in stem biomass, 53% in leaf biomass, 63% in total, main, and lateral root biomass (Tab. 2).

The relationships of increasing SPR to some biomass variables (total biomass, stem biomass, total root biomass, and main root biomass) were nearly linear, while the relationships of leaf biomass and lateral root biomass followed a negative exponential curve, indicating that reductions in the latter biomass variables were greatest between the control and the low intensity compaction treatment and decreased with increasing compaction intensity thereafter (Fig. 2). Duncan’s multiple range tests detected significant differences among all compaction intensity treatments for total biomass shoot biomass, and main root biomass (Tab. 2). Stem biomass and lateral root biomass did not significantly differ among compaction treatments except between the low and moderate intensity compaction treatments. Further, leaf biomass was not significantly different between the moderate and high intensity compaction treatments; in addition, leaf biomass was not significantly different between the control and low intensity compaction treatments (Tab. 2).

Fig. 2 - Relationship between soil penetration resistance (SPR) and biomass variables of Q. castaneifolia seedlings: total dry biomass (a), stem dry biomass (B), leaf dry biomass (C), total root dry biomass (D), main root dry biomass (E), and lateral root dry biomass (F). For each graph, the regression equation between responses and SPR and the coefficient of determination (R2) are given. (*): P<0.05; (**): P <0.01; (ns): not significant (P≥0.05).

Seedling architecture (allocation ratios)

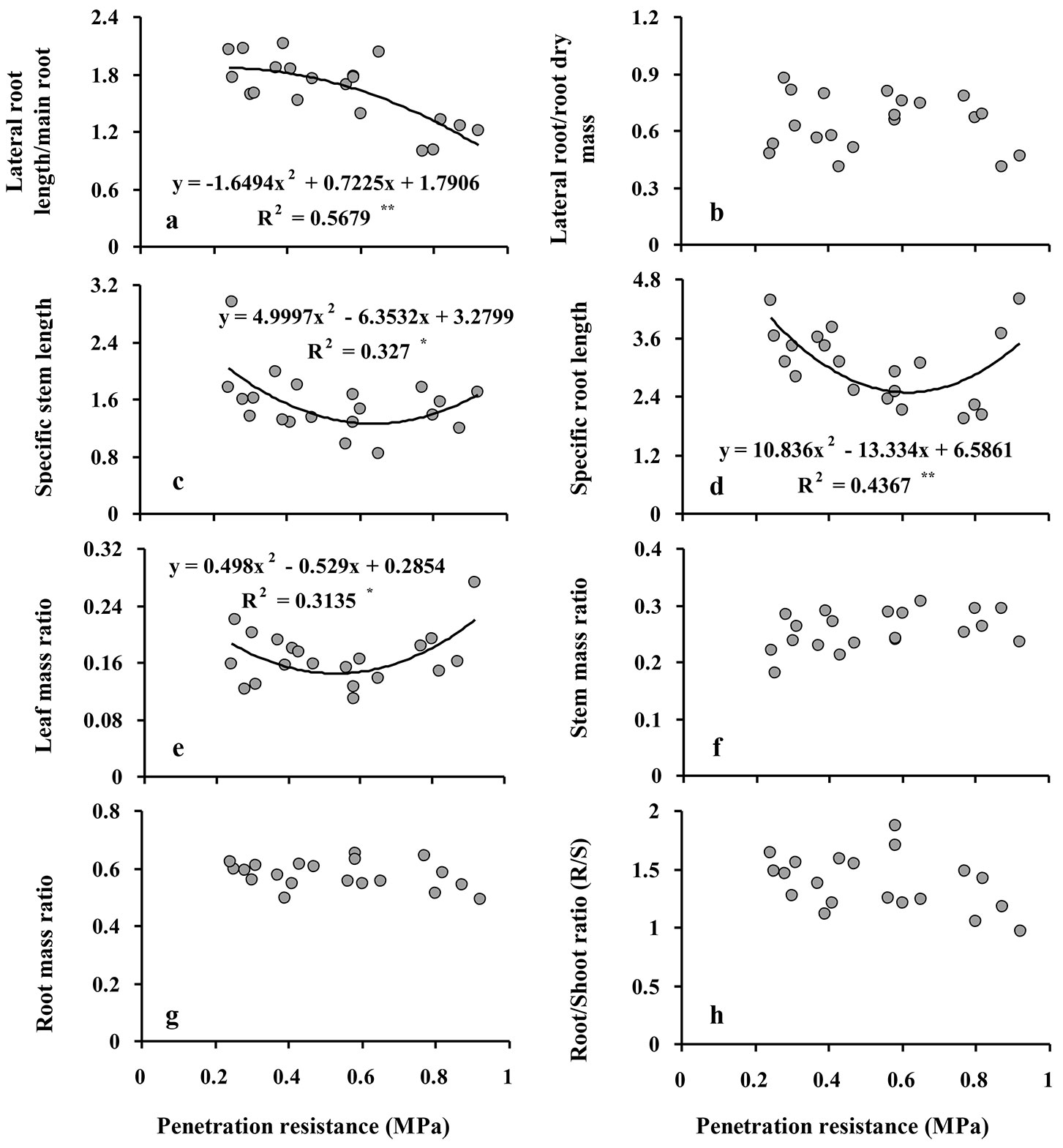

The ratio of lateral to main root length ranged from 1.82 in the control treatment to 1.16 in the high intensity compaction treatment and was significantly reduced (by 36%, P ≤ 0.001) only after soil compaction reached a high intensity; no significant differences were observed among the control, low, and moderate intensity treatments (Tab. 2, Fig. 3a). The ratio of lateral root to main root biomass was not significantly different among compaction treatments (Tab. 2, Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3 - Relationship between soil penetration resistance (SPR) and lateral root length/main root length (a) and lateral root/main root dry mass (b), specific stem length (c), specific root length (d), leaf mass ratio (e), stem mass ratio (f), root mass ratio (g), root/shoot ratio (R/S) (h) in Q. castaneifolia seedlings. For each graph, the regression equation between responses and SPR and the coefficient of determination (R2) are given. (*): P<0.05; (**): P <0.01; (ns): non-significant (P≥0.05). Models and regression lines are not shown.

Despite significant quadratic relationships indicate that a curvilinear response curve of specific stem length (SSL, the ratio of stem length to stem dry biomass) and specific root length (SRL, the ratio of fine root length to fine root weight) provided the best fit with increasing penetration resistance and with lowest values at moderate intensity compaction treatments (Fig. 3c-d), SSL and SRL were not significantly different among compaction treatments (Tab. 2).

A significant quadratic relationship was also found between leaf mass ratio (LMR, the fraction of total dry biomass in the leaves of the seedlings) and increasing penetration resistance, indicating that lowest values of LMR were observed at moderate intensity compaction treatments (Fig. 3e); however, LMR, which ranged between 14-19%, was not significantly different among compaction treatments (Tab. 2). Stem mass ratio (SMR) and root mass ratio (RMR), i.e., the fractions of total dry biomass in the stem and the root system, ranged between 24-27% (stem) and 56-60% (roots) and were not significantly different among the compaction treatments (Tab. 2, Fig. 3f-g). Finally, the ratio of root to shoot biomass (R/S) was not significantly different among compaction treatments (Tab. 2, Fig. 3h).

Discussion

Seedling morphology and growth

Increasing soil compaction strongly affected the morphology and growth of Q. castaneifolia seedlings in the greenhouse and supported our first two hypotheses that increasing soil strength would cause decreases in all variables of above-ground and below-ground seedling sizes (morphology) and biomass (growth) of the whole seedling and all of its components (i.e., above-ground: stem length, stem diameter, leaf length; biomass of stems, shoots, leaves; below-ground: main root length, main root diameter, lateral root length; biomass of main root and lateral roots). Size and biomass variables indicate that the seedlings growing in the control treatments were at least twice the size and weight of seedlings growing in the high intensity compaction treatment (this was the case for the whole seedling and for almost every above-ground and below-ground seedling component). Morphological changes of the root system, i.e., the length of lateral roots and dry biomass of the main and lateral roots were particularly striking, with reductions between 60-70%. Shorter primary and lateral roots of lower biomass observed in compacted soils are consistent with previous findings that increased soil compaction diminishes root growth ([6], [7]) and support the argument that soil compaction is an important stress factor that can adversely affect the early development of tree seedlings ([33]). Reduced root penetration, in turn, may result in restricted access to, and adsorption of, nutrients and water ([8]), leading to increases in leaf water deficits, decreases in photosynthetic rate, diminished sizes and growth of stems and the entire seedling, and even limited seedling survival under drought ([37], [34], [22], [30], [3]).

Although seedling morphology and growth exhibited consistent and predictable responses to different intensities of soil compaction in the current study, adverse effects from soil compaction are not universally observed. Soil compaction has even been reported to have a positive effect on total plant biomass, despite reductions in main root length, for some tree species over ranges of SPR comparable to our study ([2], [7]). While biomass ultimately decreased with increasing soil strength, nine out of 17 (53%) deciduous and evergreen woody species had significant increases in total biomass with increasing soil strength up to 0.5 MPa ([2]). The difference to the current study that revealed immediate decreases in biomass even below 0.5 MPa may be due to differences in soil texture and its effect on water stress. Soil water content at the time of compaction is an important determinant of the effect size of soil compaction on seedling morphology and growth. Because soil water lubricates soil particles along the elongating tip, it can alleviate excessive soil stress ([46], [16]) such that higher soil water contents are typically associated with less severe effects on seedling growth and biomass ([8]). Further, moderate compaction in soils of coarser texture can actually improve nutrient and water adsorption ([5], [22]). Thus, in the more sandy-textured soil (i.e., mixture of sand and peat) of Alameda & Villar ([2]), moderate intensity soil compaction may have facilitated greater root-soil contact ([2], [3], [7]), while in the current study compaction of loamy- to clay-textured soils, which are more easily compactable than more coarsely-textured soils ([19]), may have resulted in a lower percentage of water and air space, and perhaps more oxygen deficiency in the soil, and greater stress on plant root growth ([33], [2]). This could account for the immediate size and biomass reductions of Q. castaneifolia seedlings of 20-35% in this study, despite daily irrigation to maintain moist soil water conditions.

Seedling architecture

Our third hypothesis that increased soil compaction would cause differential growth allocation patterns to above- and below-ground portions, resulting in architectural changes to the seedlings, is mostly unsupported by our data. At first, the absence of architectural changes is somewhat surprising considering the concept of “functional equilibrium” in biomass allocation ([9], [29]). Predicated on the assumption that biomass allocation is a strong driver of a plant’s capacity to take up carbon, water, and nutrients, which strongly affects growth ([21]), resource limitation feedbacks between shoot and root growth would ensure an increase in uptake of the most limiting factor to achieve some “balanced growth” ([45]), i.e., a functional equilibrium. Thus, if the limiting factor for plant growth were below-ground (e.g., water, nutrients) induced by soil compaction, a preferential biomass allocation to the roots would maintain a balance among leaves, stems, and roots, enabling theses organs to function most optimally by matching their physiological activities at the whole plant level ([41]). In accordance with this model, plants typically respond to drought, for example, with a decrease in shoot biomass and an increase in root biomass ([26], [41]), which increases the efficiency of soil exploration and water acquisition ([38]).

Although plants under environmental or physical stress (e.g., removal of leaves or roots) are able to quickly restore allocation patterns to control levels ([9], [40]), recent research has revealed that plant responses in biomass allocation are generally modest or often entirely absent ([41]). In fact, plants seem to be less able to adjust biomass allocation than to alter organ morphology and there is little support that plants use the mechanism of allocation to adjust to their environment ([42], [41]). In this light, the lack of significant effects of soil compaction on almost all seedling architecture responses of Q. castaneifolia (i.e., SMR, LMR, RMR, R/S, SSL, SRL, and the ratio of lateral to main root dry biomass) is not surprising. Increasing soil compaction similarly failed to affect biomass allocation patterns to stems, leaves, and roots of Quercus pyrenaica Willd. ([7]) and to roots of Q. ilex subsp. ballota (Desf.) Samp., Q. canariensis Willd., and Q. pyrenaica Willd. ([2]), although allocation patterns to the roots changed for Quercus coccifera L., Q. suber L., and Q. faginea Lam. (albeit both positive and negative) under soil compaction levels comparable to this study ([2]). Further, R/S ratios typically increase with decreasing water availability ([23], [44]), but following soil compaction, R/S responses have been highly variable. R/S ratios have increased in the case of P. contorta on dry, but not moist or wet, compacted soils ([8]), decreased in the cases of Q. coccifera and Q. faginea ([2]) and Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca (Beissn.) Franco and Pinus contorta Dougl. Ex. Loud. var. latifolia Engelm. on loamy soils in British Columbia ([13]), and remained unchanged in the cases of Q. ilex, Q. canariensis, and Q. pyrenaica and an additional eight out of 17 woody species under investigation ([2]), as was also the case for Q. castaneifolia in this study. It seems clear, then, that generalizations regarding consistent mass ratio and R/S changes in response to soil compaction are inadvisable, as responses are species specific and strongly dependent on environmental factors such as soil type and soil water content ([8]), as well as light conditions ([7]).

Under conditions that limit growth, the functional equilibrium concept might suggest that the construction costs per root length would be minimized (i.e., greater SRL) to enable a large soil volume to be exploited at small cost ([43]). Greater SRL has been found to be associated with relatively high rates of root proliferation in disturbed soil and opportunistic root growth ([20]). Increased SRL, a response of many species to drought ([36]) enhance the root-soil interface and root adsorption potential ([39]), which is an advantage when soil water is limited. In contrast to Fraxinus angustifolia Vahl., where SRL was significantly reduced at bulk densities of 1.4 g cm-3 (the equivalent of moderate compaction in this study - [3]), and for Q. pyrenaica when SPR values exceeded 1 MPa ([7]), soil compaction in this study did not significantly affect SRL of Q. castaneifolia, which may be related to differences in soil attributes. We conclude that our biomass allocation results for Q. castaneifolia reflect the highly differential responses of individual species and we might infer that a threshold compaction for Q. castaneifolia had not been reached in this study, whereupon opportunistic root growth and root proliferation might be precluded. Our results should be interpreted in the context of a soil strength gradient of 0.1-1.0 MPa that equals moderate compaction intensities in other studies, and a soil water supply that did not result in water stress at any time.

Nonetheless, the only significant change in seedling architecture in this study was a shift in allocation toward relatively longer main roots compared to lateral roots. However, this shift occurred only after soil compaction had reached a high intensity. Severe compaction of soil shortens roots but may also alter their branching patterns such that the roots become more branched and form more lateral roots ([33]). This was clearly not the case in this study, however. Rather, increased soil compaction seems to have particularly affected the proportion of fine roots and decreased the growth of second-order roots, accompanied by a relatively smaller decrease in the growth of first root order ([3]). Given that fine-roots are particularly active in water and nutrient uptake, such that a greater allocation of biomass to lateral roots would be expected under conditions of water stress, the observed greater proportional allocation of biomass to the main root would rather indicate an absence of much water stress. The specific reasons for favoring the lengths of the main over lateral roots, however, are not clear.

Response thresholds

While the relationships between soil strength and morphological response variables generally followed a negative exponential shape, indicating that the changes in seedling size variables were highest per unit increase of SPR at lower soil strengths, the relationships between soil strength and growth response variables were nearly linear, with the exception of fresh and dry leaf weights. While these mixed response shapes support our fourth hypothesis that increases in soil strength are not always linearly related to the morphological and growth response variables under study, we did not find any evidence of a threshold in soil strength that has to be exceeded before sizes and growth of above- and below-ground components of Q. castaneifolia seedlings become adversely impacted. In this study, soil compaction affected seedling morphology and growth of Q. castaneifolia seedlings even at a low compaction intensity. Our results thus extend findings that any increase in soil strength may restrict root growth of woody plants ([47]) to above-ground portions of Q. castaneifolia seedlings. We conclude that growth limitations, particularly for root growth, may be induced at much lower soil strengths for some woody species than the often-cited soil strength threshold of 2-2.5 MPa ([25], [11], [46]). While this critical value may be more applicable to survival than growth ([10]), soil strength values below 2.5 MPa have been shown to reduce root growth of radiata pine (Pinus radiata D. Don. - [50]), lodgepole pine ([8]), and eucalyptus (Eucalyptus nitens Maiden - [37]) and soil strengths as low as 0.6 MPa might pose a barrier to the regeneration of cabbage tree (Cordyline australis G. Forst. - [6]). While we did not evaluate seedling mortality as a function of soil compaction in this study, our results show that for most seedling morphology and growth responses of Q. castaneifolia seedlings there is a non-linear inverse relation with SPR, with largest effect sizes at low compaction intensities and no threshold value for SPR to be exceeded for growth limitations of Q. castaneifolia seedlings to occur. On the other hand, it appears that soil compaction can eventually increase the root mass ratio in some species, but only at severe compaction ([41]) well beyond the levels obtained in this study. In this study, however, soil compaction may have been too low to divert significant growth resources either from ([2]) or toward ([2], [41]) the root system of Q. castaneifolia. Alternatively, our failure to detect significant increases in the root mass ratio, SRL, and R/S ratio, may also be due to the lack of water stress in our experiment.

Conclusions

The present study investigated changes in seedling morphology, growth, and architecture following experimentally set soil compaction levels under conditions that controlled for differences in soil texture and soil water regimes known to confound the effects of soil compaction in the field. SPR, the metric for soil compaction used in this study, is very sensitive to differences in soil texture and water content, which makes narrow extrapolations of any single compaction study result to different soil conditions challenging. While it is therefore difficult to exactly predict how much harvesting traffic would be required to reproduce identical levels of SPR in soils with different textures and water contents, the changes in seedling morphology, growth, and architecture in response to increasing soil strength are more readily generalizable. Our results clearly show that in soils of a loam to clay-loam texture with optimal conditions of water and soil strengths of up to 1.0 MPa, an increased soil compaction: (1) causes morphological changes to above- and below-ground portions of Q. castaneifolia seedlings (i.e., smaller sizes); (2) causes decreased growth (biomass) responses of the whole plant and all of the plant’s components (e.g., stem, shoot, leaves, roots); (3) does not cause significant, differential growth allocation patterns to above- and below-ground portions that result in architectural changes to the seedlings, thus making plant architecture a less sensitive response to increased soil compaction than size/growth and not a very reliable predictor of size/growth responses; (4) typically results in non-linear size and growth responses with large negative effects at low soil compaction intensities; and (5) does not exhibit a critical soil threshold before size and growth responses become adversely affected.

List of abbreviations

The following abbreviations were used throughout the manuscript:

- SPR: soil penetration resistance

- BD: bulk density

- TP: total porosity

- PD: particle density

- SSL: specific stem length

- SRL: specific root length

- SMR: stem mass ratio

- LMR: leaf mass ratio

- RMR: root mass ratio

- R/S: root-to-shoot ratio

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Iran National Science Foundation (INSF), project No. 93014726. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments which improved the manuscript.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Azadeh Khoramizadeh

Department of Forestry and Forest Economics, University of Tehran, Zob-e-Ahan Street, 315854314 Karaj (Iran)

College of Agricultural Sciences, Pennstate University, 305 Forest Resources Building, University Park, 1680 PA (USA)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Jourgholami M, Khoramizadeh A, Zenner EK (2016). Effects of soil compaction on seedling morphology, growth, and architecture of chestnut-leaved oak (Quercus castaneifolia). iForest 10: 145-153. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1724-009

Academic Editor

Renzo Motta

Paper history

Received: May 29, 2015

Accepted: Feb 14, 2016

First online: Jun 13, 2016

Publication Date: Feb 28, 2017

Publication Time: 4.00 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2016

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 51571

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 41483

Abstract Page Views: 4135

PDF Downloads: 4502

Citation/Reference Downloads: 40

XML Downloads: 1411

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 3530

Overall contacts: 51571

Avg. contacts per week: 102.27

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2017): 24

Average cites per year: 2.67

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Influence of slope on physical soil disturbance due to farm tractor forwarding in a Hyrcanian forest of northern Iran

vol. 7, pp. 342-348 (online: 17 April 2014)

Research Articles

Short-term effects in canopy gap area on the recovery of compacted soil caused by forest harvesting in old-growth Oriental beech (Fagus orientalis Lipsky) stands

vol. 14, pp. 370-377 (online: 10 August 2021)

Research Articles

Influences of forest gaps on soil physico-chemical and biological properties in an oriental beech (Fagus orientalis L.) stand of Hyrcanian forest, north of Iran

vol. 13, pp. 124-129 (online: 07 April 2020)

Short Communications

Seasonal change in soil nitrogen mineralization in young Chamaecyparis obtusa stands at the upper and lower positions on a slope in central Japan

vol. 18, pp. 197-201 (online: 20 July 2025)

Research Articles

Photosynthesis of three evergreen broad-leaved tree species, Castanopsis sieboldii, Quercus glauca, and Q. myrsinaefolia, under elevated ozone

vol. 11, pp. 360-366 (online: 04 May 2018)

Research Articles

Effects on soil physicochemical properties and seedling growth in mixed high forests caused by cable skidder traffic

vol. 16, pp. 127-135 (online: 23 April 2023)

Research Articles

Investigations on yellowing of chestnut crowns in Trentino (Alps, Northern Italy)

vol. 13, pp. 466-472 (online: 07 October 2020)

Research Articles

Dynamics of humus forms and soil characteristics along a forest altitudinal gradient in Hyrcanian forest

vol. 14, pp. 26-33 (online: 10 January 2021)

Research Articles

Impact of deforestation on the soil physical and chemical attributes, and humic fraction of organic matter in dry environments in Brazil

vol. 15, pp. 465-475 (online: 18 November 2022)

Research Articles

Soil stoichiometry modulates effects of shrub encroachment on soil carbon concentration and stock in a subalpine grassland

vol. 13, pp. 65-72 (online: 07 February 2020)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword