Does management improve the state of chestnut (Castanea sativa L.) on Belasitsa Mountain, southwest Bulgaria?

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 8, Issue 6, Pages 860-865 (2015)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1420-008

Published: Apr 27, 2015 - Copyright © 2015 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Chestnut forests in the Belasitsa Mountain region of southwest Bulgaria were traditionally intensively managed as orchard-like stands for nut production. More recently, management intensity has been sharply reduced as a result of rural abandonment, which combined with the effects of chestnut blight has led to marked structural changes in these forests. The focus of this paper is on the seed-based regeneration potential and seedling survival of chestnut in mixed stands managed over the past 15 years. Results suggest that management of stands under a high-forest system is appropriate, and regeneration from seed has advantages over coppicing if competing species can be controlled. An investigation into “sanitation cutting” performed since the 1990s shows that this had not a successful response to blight infestations.

Keywords

Castanea sativa, Chestnut Blight, High-forest System, Seed-based Regeneration

Introduction

For many centuries European chestnut forests have been mostly managed as short rotation coppices and orchards for nut production ([5], [17]). During the second half of the 20th century chestnut cultivation substantially decreased because rural populations fell and the species became less important as a staple food. Chestnut trees also sustained substantial damage from chestnut blight caused by the fungus Cryphonectria parasitica (Murrill) Barr ([8], [36]) and from ink-disease caused by Phytopthora spp. Abandoned open-structured chestnut stands and coppices have both been partially replaced by climax communities associated with various Quercus or Fagus species ([28], [40], [38], [7], [20], [11], [18], [32], [33], [49]).

In recent years, biological control of chestnut blight and the natural spread of hypovirulence throughout most of Europe ([24]) allowed chestnut to be again a viable species for wood production. The increasing demand for high-quality wood production has fostered a discussion about identifying appropriate management techniques to assure sustainable forest management for sawlog production ([14], [2], [21]). As a result, the production of high-value chestnut timber is now being enhanced in some parts of Europe where growing conditions are appropriate ([7]). However, this was mainly achieved by extending the rotation of coppices up to 30 or 50 years rather than by management of chestnut in high forests originating from seed ([5], [3], [4]). Currently, there are few experiments into how chestnut regenerates and grows under high-forest silvicultural methods, even though these methods are extensively used in most mixed deciduous forests in Europe ([8]). Hence, little is known of how the behavioral patterns of chestnut could be managed to secure its future survival in species-rich mixed forests under a high-forest system.

After a period of abandonment in the first half of the 20th century, interest in the management of chestnut stands on the Belasitsa Mountain (southwest Bulgaria) rose again in the 1990s, as a consequence of the spread of the chestnut blight disease. The first documented identification of C. parasitica on Belasitsa Mountain was in 1993 ([31]). Management response was confined to the implementation of sanitation cuttings through the harvesting of trees with heavily damaged crowns (degree of damage > 60%). The first sanitation cuttings in chestnut-dominated and co-dominated stands on the mountain were carried out in 1989. More than 2700 m3 of chestnut wood were harvested up to 1992. From 1993, the magnitude of wood harvested in sanitation cuttings substantially increased. To 2006 more than 30 000 m3 of chestnut wood were harvested. Since 2006, the intensity of sanitation cuttings abruptly decreased and they were replaced by clearcuts in small patches ([46]).

It is currently under debate how forest management should be adapted to better utilize the potential chestnut-dominated and co-dominated forests on the northern slopes of Belasitsa Mountain. The forestry community in Bulgaria has never regarded their transformation into coppice stands as a viable alternative, mainly on the grounds of regional historical traditions of chestnut management as high forests. According to Zlatanov et al. ([48]), sustainable management of chestnut on Belasitsa Mountain in high forest systems seems to be in principle possible, on account of the retained seed regeneration potential of the species. This is expected to increase the production of high-value chestnut timber, at least on favorable sites ([23]), without endangering the social (e.g., nut collection) and ecological (habitat for many animal species) values of the stands. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to: (i) study and evaluate the effects of recent management (over the past 20 years) on the health and regeneration status of chestnut; and (ii) evaluate options for future forest management.

Materials and methods

Study area and sampling design

Although Belasitsa Mountain is situated comparatively close to the Mediterranean Sea (approx. 100 km), the climate on its northern slopes favors the development of forest vegetation. The average annual precipitation at lower altitudes (where chestnut forests grow) is between 650 mm (500 m a.s.l.) and 800 mm (1000 m a.s.l.). The mean annual temperature varies between 13 °C (500 m a.s.l.) and 9 °C (1000 m a.s.l.). Chestnut stands grow on steep and moderately steep slopes (20-40°) with predominantly northern exposures. The soil is a moderately rich loamy-sand Eutric Cambisol with depth mostly varying between 50 and 80 cm. The current area of chestnut dominated and co-dominated stands in the Bulgarian part of Belasitsa Mountain totals 1678 ha, which is approximately 20% of the total forested area on the mountain ([45]).

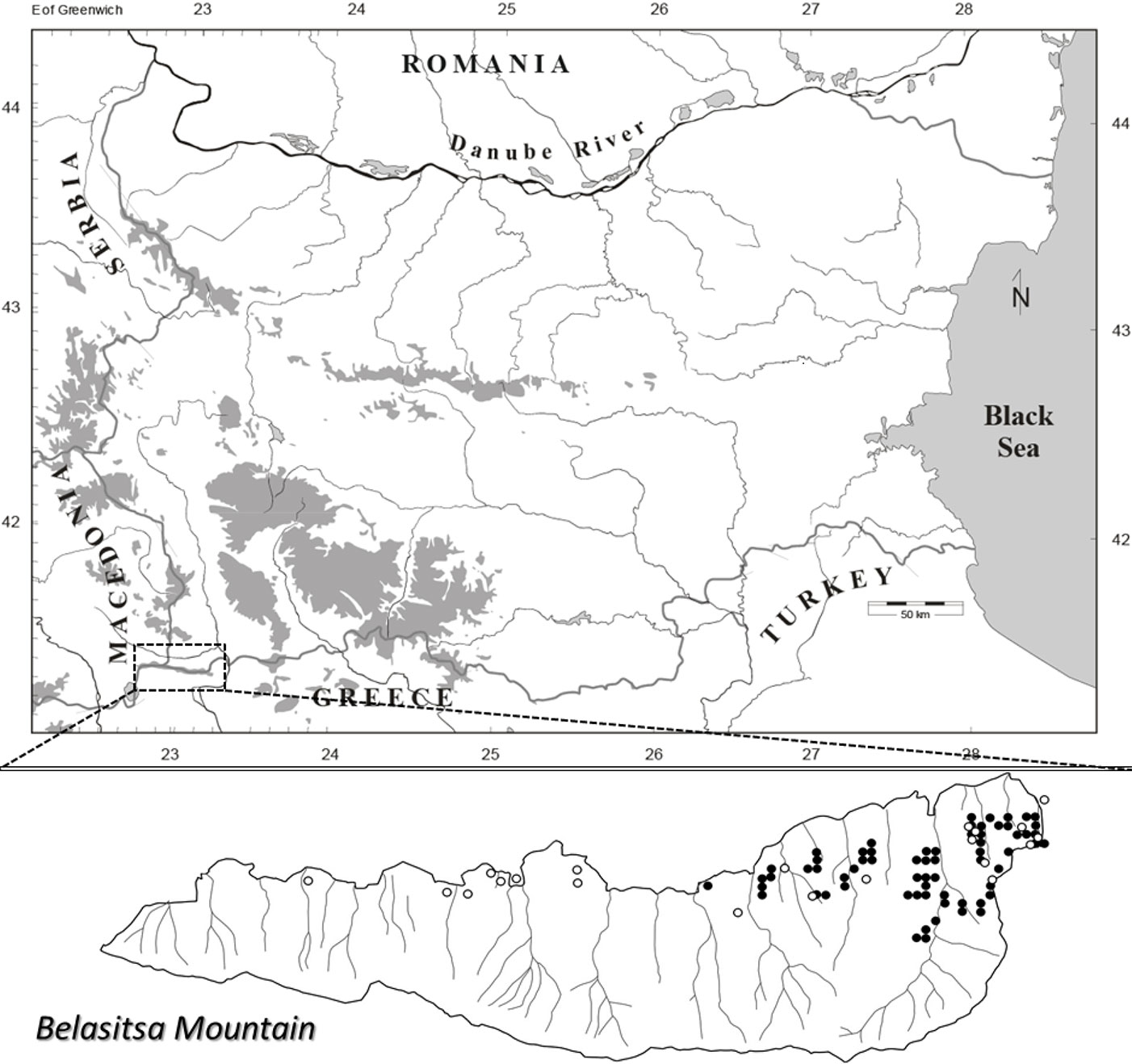

Data for the current study was collected from a systematic network of sample plots and in patch cuts performed in chestnut dominated forests. As part of the systematic sampling approach, a grid was drawn across the most recently updated forestry map of Belasitsa Mountain ([34]). The interval between grid lines was set to 250 m in both longitudinal and latitudinal directions. A total of 67 grid intersections fell within the boundaries of chestnut dominated stands (as depicted in [35]). In the second step, 50 grid intersections (Fig. 1) were randomly selected from the 67 described above. Accordingly, 50 permanent sample plots sized 0.126 ha (40 m in diameter) were established, with plot centers at the intersection point of the selected grid. Grid intersections were placed on the field by GPS (Trimble Juno SB). Additionally, a total of 21 patch cuts were found in mature stands dominated by chestnut and used in the analyses.

Fig. 1 - Study area and location of research plots. Black circles represent the plots in the systematic network of sample plots, and white circles represent the plots in the patch cuts.

Field measurements

Measurements in the systematic network of sample plots were performed in 2011. In each plot, the number of all trees larger than 8 cm at breast height (total and by species) was assessed and the number of stumps counted in order to determine the sanitation cut intensity. The degree of crown damage of chestnut trees was surveyed in the period June-August. Damage classes were defined using UNECE and EU standardized criteria ([10]). Damage of more than 25% was taken as a threshold for classifying a tree as “damaged” and of more than 60% as “heavily damaged”. The occurrence of symptoms or signs of the chestnut blight disease caused by C. parasitica was revealed by the presence of numerous completely dry branches in the crowns of infected trees. The presence of infection symptoms such as bark necrosis, reproductive fungal structures and mycelia fans of C. parasitica in the inner bark of the chestnut individuals were also considered ([13]). Recent virulent infections of the fungus were detected by the wilting of young branches and dry leaves remaining on the killed twigs. No occurrences of ink disease (caused by Phytophtora spp.) or Asian gall wasp (Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu) were observed in this study. Although ink disease is an important cause of rot and defoliation of chestnut elsewhere in Europe, it is not currently considered a serious problem in the forests of the Belasitsa Mountain region ([12]).

Regeneration parameters were assessed in four nested quadrats in each plot. The nested quadrats were set in four directions (North, East, South and West) at 10 meters distance from the plot center. Two regeneration measurement plots of 1 and 3 meters of radius were installed in each quadrat. Parameters of seedlings (individuals of up to 1.3 m in height) and saplings (individuals of more than 1.3 m in height and up to 8 cm in dbh) were assessed from the 1 m and 3 m plots respectively. All individuals in the regeneration stratum were counted and species identified. Chestnuts were additionally classified according to their crown quality. All chestnuts not damaged or subjected to repeated die-back and re-sprouting processes due to heavy suppression (“bush-like” crowns) and also with no disease symptoms were referred to as having potential for further silvicultural treatments (“morphologically good condition”). Others were classified as having “morphologically bad condition”. Finally, the most recent shoot growth of all chestnuts of morphologically good condition was measured. Field measurements in harvested patches were performed in 2013. For that purpose, a linear transect was drawn across the longer dimension of each patch. Nested quadrats were set every 10 meters along the transect line. Seedling and sapling parameters were assessed using the protocol described for mature stands. A minimum of five quadrats were installed in each patch.

Data analyses

Hierarchical regression analyses were used to explain the variation at the plot scale in the crown damage of chestnut trees (eqn. 1) and in the regeneration attributes (eqn. 2):

where Pdf(25, 60) is the proportion of chestnut trees with 25 or 60 percent of crown damage, Alt is the altitude, HI is the sanitation cut intensity (not used in analyses of patch cuts), IAH represents the years after harvest, Dt and Dcs are total and chestnut regeneration density, Dcsf is the density of chestnuts in the regeneration having potential for further silvicultural treatment (of morphologically good condition), Pcsfs and Pcsfc are the proportions of morphologically good chestnut regenerated through seed (csfs) and coppice (csfc), and LSGcsfs and LSGcsfc are the most recent shoot growth of morphologically good trees.

Alt was entered into the models first and then HI and IAH. The choice of altitude as the only site-defining explanatory variable was based on past research in the area ([49]). Due to the large variance in response variables, 95% confidence intervals were computed for the parameter estimates using a bootstrap resampling procedure ([22]). With this approach, each of the original data sets was repeatedly sampled with replacement to generate 2000 new data sets equal in size to the original. Parameter estimates were calculated for each of these resampled data sets, and used to derive sampling distributions for the transition probabilities of interest. The 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of these sampling distributions defined the lower and upper bounds of 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for each parameter. Bias corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (BCaCI - [9]) that adjust for both bias and skewness in the bootstrap distribution are reported.

Results

Mature stands

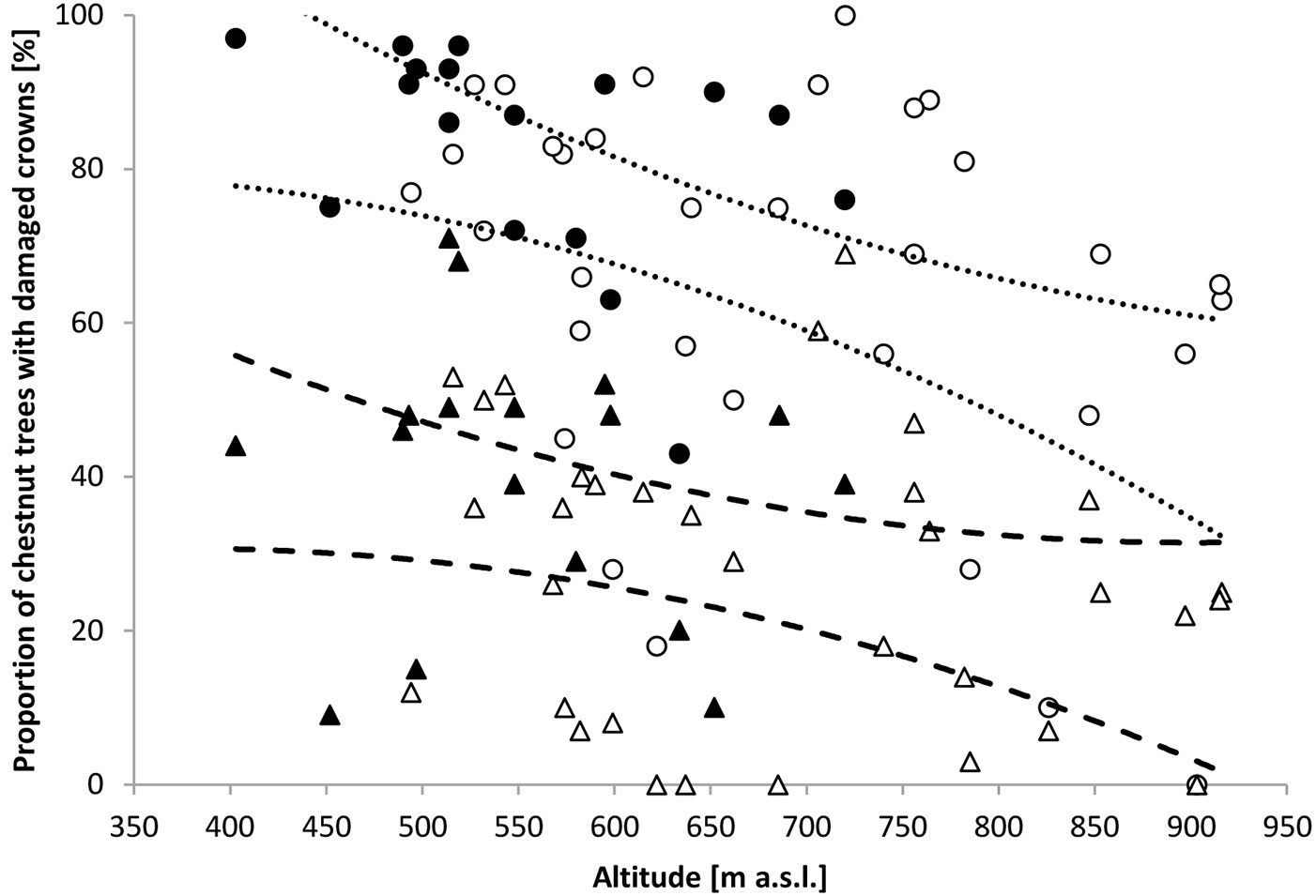

The proportion of chestnut in the species composition of mature stands averaged 53% (Q25=32%, Q75=81%). It was predominantly mixed with sessile oak (Quercus petraea Liebl.) at elevations of up to 800 m a.s.l. and with European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) above 700 m a.s.l. Individuals of hop-hornbeam (Ostrya carpinifolia Scop.) and silver lime (Tilia tomentosa Moench.) were also found in most plots across the altitudinal gradient. In 42 of the 50 plots more than 50% of chestnut trees were characterized by damaged crowns. The proportion of damaged trees exceeded 70% in 31 plots. In 32 plots, more than 25% of chestnuts were heavily damaged. All damaged chestnut trees were characterized by symptoms or indicators of chestnut blight disease. When Alt was entered into the hierarchical regression models by itself, it significantly predicted the variation in Pdf25 (0.05 ≤ BCaCI of R2 ≤ 0.42 - Fig. 2) and in Pdf60 (0.01 ≤ BCaCI of R2≤ 0.26). HI and IAH (which varied between 15% and 50% and between 4 and 15 years respectively) did not significantly improve the prediction of the variation of either Pdf25 or Pdf60.

Fig. 2 - Proportion of chestnut trees with damaged (circles) and heavily damaged (triangles) crowns at the plot scale. Black symbols represent plots in which sanitation cuts were performed. Dotted lines represent the 95% confidence intervals of Pdf25=α+βAlt; 101.3 ≤ BCaCI of α ≤ 155.9; -0.137 ≤ BCaCI of β ≤ 0.045; dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals of Pdf60=α+βAlt; 37.6 ≤ BCaCI of α ≤ 82.48; -0.079 ≤ BCaCI of β ≤ 0.010.

Dt averaged 15 000 ha-1 (Q25=7300 ha-1, Q75 =25 000 ha-1). In addition to the main overstorey tree species, other tree and shrub species components comprising more than 3% of the regeneration stratum included flowering ash (Fraxinus ornus L.) and common hazel (Corylusa vellana L.). Mean Dcs was 3300 ha-1 (Q25=1900 ha-1, Q75=4800 ha-1). Fifty five percent of all chestnut individuals were of seed origin. Dcsf averaged 2400 ha-1 (Q25=1400 ha-1, Q75=3500 ha-1). Seventy eight percent of seed-originated chestnuts were of morphologically good condition, while 62% of chestnut coppice shoots were of morphologically bad condition, mostly infected by C. parasitica or Diplodina castaneae Prill. & Delacr. On average LSGcsfs and LSGcsfc were respectively 4cm (Q25=3 cm, Q75=7 cm) and 7 cm (Q25=5 cm, Q75=10 cm). None of the regeneration parameters in the mature stands were significantly predicted (at α≤0.05) by the regression models (eqn. 2).

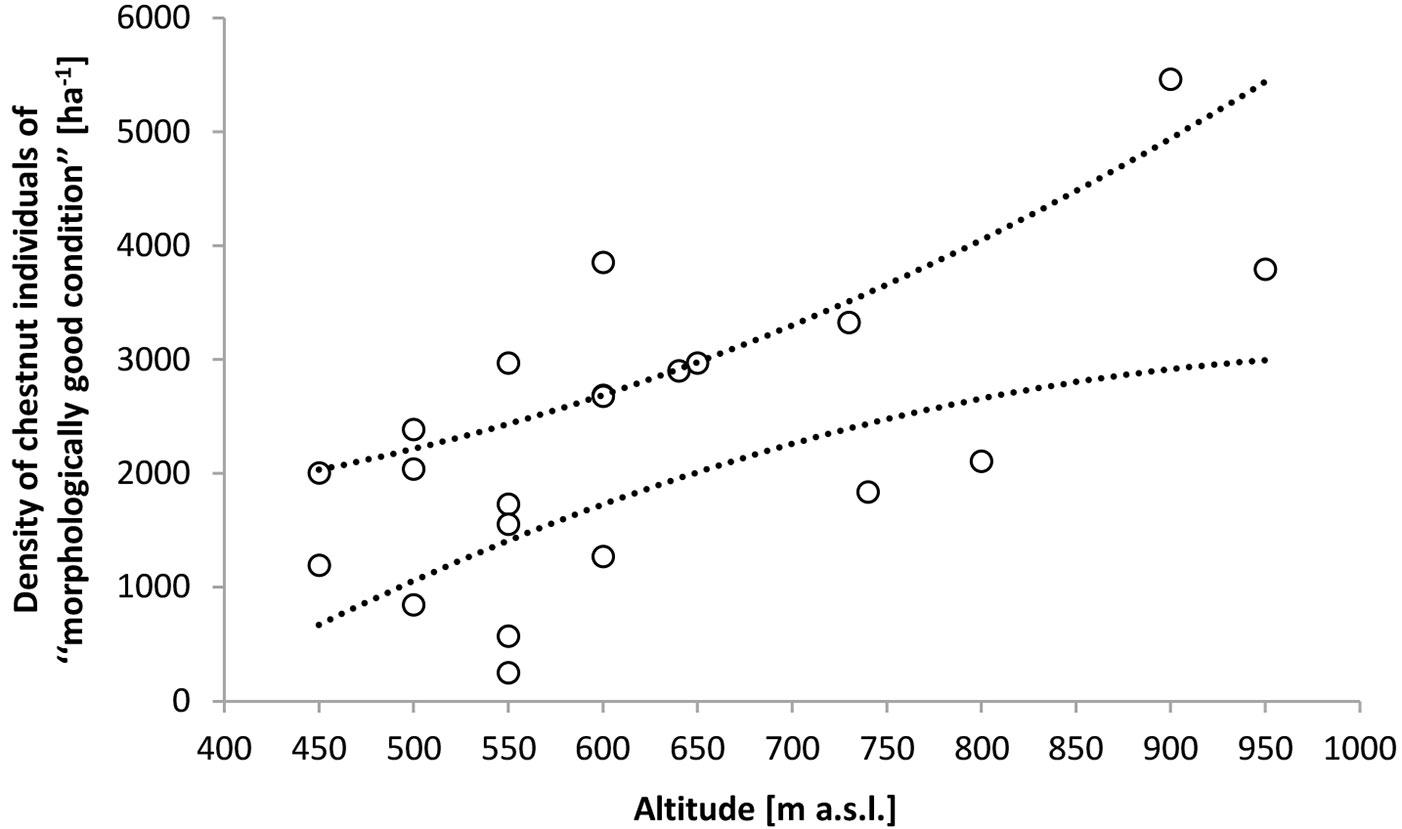

Patch cuttings

The regeneration stratum in patch cuttings was characterized by high species richness. A total of 38 tree and shrub species were identified. Besides chestnut, the following species comprised more than 3% of the species mix: sessile oak, European beech, silver lime, common hazel and flowering ash. Dt and Dcs in patch cuttings averaged 13 700 ha-1 (Q25=10 600 ha-1, Q75=17 100 ha-1) and 3400 ha-1 (Q25=2500 ha-1, Q75=3900 ha-1) respectively. The variation in these parameters was not significantly predicted by Alt and IAH. Forty nine percent of all chestnut individuals were of seed origin. Alt by itself significantly predicted the variation in Dcsf (0.19 ≤ BCaCI of R2 ≤ 0.61 - Fig. 3). When IAH (ranging between 1 and 9) was added to the regression model it was not a significant predictor of Dcsf (BCaCI of the parameter estimate varied between -182.24 and 110.09). The variation in Pcsfs was not significantly predicted by Alt and IAH. On average 99% (Q25=95%, Q75=100%) of all seed-originated chestnut individuals were of morphologically good condition. However, forty two percent of the latter were under increasing competition from coppice shoots (in particular those of chestnut, common hazel and silver lime). Both Alt and IAH significantly explained the variation in Pcsfs (Pcsfs=a+bAlt+cIAH; 0.32 ≤ BCaCI of R2 ≤ 0.69; 1 ≤ BCaCI of a ≤ 42.8; 0.069 ≤ BCaCI of b ≤ 0.173; -8.736 ≤ BCaCI of c ≤ -3.677). On average, 62% of coppice-originated chestnuts were of morphologically good condition, but were only 38% in cuttings older than 5 years and at elevations of up to 600 m. Ninety seven percent of all coppice chestnuts classified as being of morphologically bad condition were infected by Cryphonectria parasitica. Neither LSGcsfs nor LSGcsfc were significantly (at α≤0.05) associated with Alt and IAH. On average LSGcsfs and LSGcsfc were 60cm (Q25=30 cm, Q75=80 cm) and 70 cm (Q25=50 cm, Q75=100 cm), respectively. The LSG of the most common non-chestnut tree and shrub species averaged as follows: sessile oak 10cm (Q25=5 cm, Q75=20 cm), European beech 5cm (Q25=5 cm, Q75=10 cm), silver lime 60cm (Q25=20 cm, Q75=85 cm), common hazel 55 cm (Q25=30 cm, Q75=85 cm) and flowering ash 40 cm (Q25=20 cm, Q75=55 cm).

Fig. 3 - Density of chestnut individuals having potential for further silvicultural treatments (of “morphologically good condition”). Dotted lines represent the 95% confidence intervals of Dcsf=α+βAlt; -3128 ≤ BCaCI of α ≤ -22; 2.737 ≤ BCaCI of β ≤ 9.889.

Discussion

To date, research aimed at the restoration of European chestnut has been largely focused on the control of C. parasitica, and in particular on the development of biological methods to this goal ([6], [15], [25]). According to Turchetti & Maresi ([44]), the level of chestnut blight damage in Europe is decreasing as a consequence of the development of hypovirulent strains of a viral parasite that attacks the fungus. Several recent attempts have been made to determine whether or not natural hypovirulence is present in chestnut in our study area ([12]), but as yet no study has observed healing or healed cankers and the presence of hypovirulence has not been proven through laboratory tests. Results from this study showed that chestnut blight tends to enter its chronic phase without biological control; fungus is widespread over the mountain with considerable negative impact on chestnut health, especially at lower altitudes. This is in accordance with the findings of several previous research ([19], [14], [30], [29], [1], [25]).

It was expected in the 1990s that sanitation cuts would improve the health status of chestnut in chestnut dominated and co-dominated stands on Belasitsa Mountain. Amorini et al. ([4]) reported that thinning, even if it seems to increase the spreading of C. parasitica, actually improves the vegetative condition of the stands, both directly through removing the virulent cankers and indirectly by increasing the individual tolerance to the disease by selection of the most vigorous trees. Our longer-term study, however, found no significant association between the intensity of sanitation cuts and the proportion of chestnut trees with more than 25 or 60 percent of crown damage. According to Prospero et al. ([39]), C. parasitica readily survived in cankers for more than 1 year after cutting of trees and considerable saprophytic activity and sporulation of the pathogen on the bark of recently dead chestnut wood was observed. As a necrotrophic bark fungus, C. parasitica probably exploits the weakened host defense mechanisms, as well as the favorable conditions of the moribund bark substrate after trees are cut.

Closed canopies of mature stands with a substantial chestnut component provide low and uniform light availability for the reproduction stratum, which explains the weak shoot growth of the light-demanding, seed-regenerated chestnut individuals ([38]). Our results suggest that sanitation cuts did not improve the growth of chestnut seedlings. Zlatanov et al. ([49]), using hemispherical photographs in chestnut dominated forests, found that they have the potential to rapidly fill newly opened canopy gaps, mainly due to the rapid growth of the species-rich shrub storey, which usually remains intact during harvest operations. Therefore, the sanitation cuts did not serve as a proper seeding felling in the sense of the “shelterwood system”, as expected at the time of their implementation. G. Gogushev (unpublished data) ascertained that the removal of all beech trees in a mature randomly mixed beech-chestnut stand located in the upper part of the distribution range of chestnut on Belasitsa Mountain (900 m a.s.l.) had a much better effect than sanitation cuttings in achieving regeneration of chestnut and beech five years after harvest. The growth of chestnut seedlings exceeded that of the beech, with the shrub understorey being less prominent than at lower altitudes.

The implementation of a final regeneration harvest consistent with the biology of the species and their reproductive strategy is important to achieve a desired species mix in the new stand ([27], [47]). Chestnut is characterized seedlings that grow quickly under full light. In this respect, it has an advantage over seedlings of other tree species such as European beech, sessile oak and silver lime when regenerating in mixed stands ([46]). Our results indicate that nearly half (49%) of chestnut individuals in patch cuttings were of seed origin. Their importance in regenerating the stands is clear from their good quality and health across the age and altitudinal gradients (on average 99% of chestnut seedlings in patch cuttings were not damaged and without chestnut blight disease symptoms). Chestnut seedlings were capable of rapid growth (most recent shoot growth of 60 cm, on average) during the first nine years after the mature canopy final harvest and regardless of altitude. Only coppice shoots of chestnut (average LSG of 70 cm) and some of the other admixed species have the potential to overtop chestnut seedlings. An especially influential competitor of chestnut seedlings is the common hazel (average LSG of 55 cm). As ascertained in the current study, such species not only participates in the understory of mature chestnut-dominated and co-dominated stands, but also develops rapidly growing coppice shoots after harvest. Another important competitor is the silver lime (average LSG of 60 cm). The reproductive strategy of this species is to form fast growing root suckers, which grants a great advantage in clear cuttings ([16], [43]). As a result, silver lime forms biogroups that compete in growth with both chestnut seedlings and coppice shoots. As shown in the results, chestnut coppice shoots appeared to become less reliable with age, especially at lower elevations, where they were highly susceptible to chestnut blight disease. The very high susceptibility of coppice shoots to chestnut blight is confirmed by T. Zlatanov (unpublished data) for 12 to 15 year old chestnut stands of coppice origin in the Macedonian part of Belasitsa Mountain, in which the proportion of shoots with symptoms of the disease was as high as 90 percent.

Implications for management

Sanitation cuts performed in chestnut-dominated and co-dominated stands on Belasitsa Mountain did not improve either the chestnut health status or the species regeneration potential, hence we do not have sufficient evidence to support their further implementation in the region. The absence of intensive ongoing management may have biodiversity advantages: Nikolov et al. ([26]), Simov ([41]) and Popov ([37]) emphasized the importance of the large snags and rotting logs in chestnut forests on Belasitsa Mountain in providing habitat for many associated species of high conservation value, both on a European and a national scale. This includes various woodpecker species (especially White-backed Woodpecker Dendrocopos leucotos), Semi-collared Flycatcher (Ficedula semitorquata), bat species etc.

In this study, we observed a high proportion of seed-originated chestnuts not damaged and with no chestnut blight disease symptoms both in non-managed stands and in stands subjected to sanitation cuts. This suggests that chestnuts have retained a high regeneration potential, as it was well manifested in patch cuttings where the development of a new coppice stand was started, as well as the growth of a new seed-originated cohorts of chestnut and other valuable tree species such as European beech and Sessile oak. This successful seed regeneration is a prerequisite for the implementation of high forest silviculture as a valid alternative either to abandonment or management as coppice stands.

Selection of an appropriate silvicultural system poses a great challenge for management of chestnut-dominated and co-dominated stands on Belasitsa Mountain. Based on the results of the current research, a patch cut system (after [42]) might be recognized as the preferred type of clearcut silvicultural system, promoting natural regeneration in small openings. All definitions of patch cuts include the concept of small openings that will be managed as individual stand units, unlike the openings created in the irregular shelterwood systems. The application of the latter seems also appropriate to the reproduction strategy of chestnut, but would require a more comprehensive planning in order to assure synchronization in increasing the patches in several steps until the entire stand has had the overstorey removed. The advantages of both systems are related, with possibilities for multipurpose management (including seed production and biodiversity conservation) and maintenance of a more complex forest structure. It is difficult to predict the long term development of chestnut in the new stands, even under the assumption of properly performed early release treatments and precommercial thinnings (both are recommended), due to the generally unfavorable health status of chestnut in the area. The introduction of hypovirulence-based biological controls of C. parasitica might be well justified and capable of protecting susceptible chestnut trees.

Acknowledgements

Support for this study was provided by the European Economic Area as part of the project BG 0031 “State and prospects of the Castanea sativa population in Belasitsa mountain: climate change adaptation; maintenance of biodiversity and sustainable ecosystem management”, as well as by the European Regional Development Fund and the state budget of the Republic of Bulgaria through the project DIR-5113326-7-101 “Implementation of Activities for the Management of Belasitsa Nature Park”.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Ivaylo Velichkov

Margarita Georgieva

Georgi Hinkov

Magdalena Zlatanova

Forest Research Institute - Sofia, 132 St. Kliment Ohridski Blvd., 1756 Sofia (Bulgaria)

Regional Forest Directorate, Blagoevgrad (Bulgaria)

School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, PO Box 157, Lismore NSW 2480 (Australia)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Zlatanov T, Velichkov I, Georgieva M, Hinkov G, Zlatanova M, Gogusev G, Eastaugh CS (2015). Does management improve the state of chestnut (Castanea sativa L.) on Belasitsa Mountain, southwest Bulgaria?. iForest 8: 860-865. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1420-008

Academic Editor

Alberto Santini

Paper history

Received: Aug 04, 2014

Accepted: Jan 23, 2015

First online: Apr 27, 2015

Publication Date: Dec 01, 2015

Publication Time: 3.13 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2015

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 52289

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 43529

Abstract Page Views: 3465

PDF Downloads: 3801

Citation/Reference Downloads: 21

XML Downloads: 1473

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 3961

Overall contacts: 52289

Avg. contacts per week: 92.41

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2015): 4

Average cites per year: 0.36

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Effects of drought and nutrient deficiency on grafts originating from sound and shaken sweet chestnut trees (Castanea sativa Mill.)

vol. 9, pp. 109-114 (online: 19 July 2015)

Research Articles

The complexity of mycobiota associated with chestnut galls induced by Dryocosmus kuriphilus in Galicia (Northwestern Spain)

vol. 17, pp. 378-385 (online: 14 December 2024)

Research Articles

Case study of a new method for the classification and analysis of Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu damage to young chestnut sprouts

vol. 5, pp. 50-59 (online: 10 April 2012)

Research Articles

Investigations on yellowing of chestnut crowns in Trentino (Alps, Northern Italy)

vol. 13, pp. 466-472 (online: 07 October 2020)

Review Papers

Should the silviculture of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) stands in northern Africa be oriented towards wood or seed and cone production? Diagnosis and current potentiality

vol. 12, pp. 297-305 (online: 27 May 2019)

Research Articles

Fungal community of necrotic and healthy galls in chestnut trees colonized by Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae)

vol. 12, pp. 411-417 (online: 13 August 2019)

Research Articles

Density management diagrams for sweet chestnut high-forest stands in Portugal

vol. 10, pp. 865-870 (online: 06 November 2017)

Research Articles

Seed trait and rodent species determine seed dispersal and predation: evidences from semi-natural enclosures

vol. 8, pp. 207-213 (online: 28 August 2014)

Research Articles

Tree-oriented silviculture: a new approach for coppice stands

vol. 9, pp. 791-800 (online: 04 August 2016)

Research Articles

Gnomoniopsis castaneae associated with Dryocosmus kuriphilus galls in chestnut stands in Sardinia (Italy)

vol. 10, pp. 440-445 (online: 24 March 2017)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword