Impact of wheeled and tracked tractors on soil physical properties in a mixed conifer stand

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 9, Issue 1, Pages 89-94 (2015)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1382-008

Published: May 22, 2015 - Copyright © 2015 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Damage to forest soil caused by vehicle traffic mainly consists of soil compaction, displacement, and rut formation. Severity of the damage depends on vehicle mass, weight of the carried loads, ground morphology, and soil properties, such as moisture. This paper investigates the impacts of two types of vehicles (tracked or wheeled tractor), traffic intensities (one or five skidding cycles) and soil moisture (24% or 13% by weight) on compaction of a loam textured soil in a mixed conifer stand of central Italy. Changes in porosity, bulk density, shear and penetration resistances were analyzed. The latter three parameters were significantly higher in the trafficked soil portions than in the undisturbed ones in all treatments, while the opposite was true for porosity. The impact on soil bulk density and porosity was stronger for the wheeled tractor working on moist soil, while no significant effect of soil moisture was recorded for the tracked tractor. Shear and penetration resistances increased as a consequence of traffic, depending on both tractor type and soil moisture. The largest impact on shear resistance was recorded for the wheeled tractor on moist soil, while significant differences in penetration resistance were observed only between tracked and wheeled tractors in dry soil conditions. In order to preserve soil quality during logging activities, we recommend to operate under dry soil conditions and to limit vehicle movement on existing or new planned trails.

Keywords

Soil Compaction, Rutting, Skid Trails, Soil Degradation, Forest Management

Introduction

The negative impact of heavy logging equipment on the physical properties of soil is well known ([25], [7], [36], [54], [48], [45], [41], [35]). The subject was recently reviewed in Ampoorter et al. ([3]) and Cambi et al. ([13]). Forest operations, such as forwarding and skidding, have a high potential for soil compaction ([31]). Soil compaction is a major source of human-induced forest soil degradation ([6]), even though moderate compaction of loose soils can result in improved soil quality ([19]). Harvest-induced soil compaction depends on several factors: soil type ([9], [44], [34]), soil moisture ([36], [20], [3]), content of soil organic matter ([5]), number of machine passes ([57], [55], [20]), terrain steepness and direction of travel ([33]), characteristics of the equipment and yard organization ([41], [35]), and machine speed and wheel slippage ([1], [17]). Soil compaction and reduction or removal of the top organic horizon often causes poor regeneration on skid trails ([42], [52]). With the exception of coarse-textured, excessively drained soils ([30], [19]), soil compaction reduces forest productivity ([11], [23], [4]) by impairing root elongation and decreasing water and air supply to plants and soil biota ([56]). Soil compaction may also increase surface runoff and erosion ([42], [57], [15]) , hence the loss of the topmost fertile soil. Rutting is a frequent undesired result of forest logging and consists of grooves, caused by soil compression and displacement, which become preferential flow paths ([24]). Rut formation suggests that the load imposed onto the soil has exceeded its bearing capacity ([37]). The weight of a loaded vehicle and the number of passes are major factors of rut formation ([32], [36], [12], [17]). Ruts are usually more marked by wheeled vehicles than by tracked vehicles, due to higher pressure on soil, and for moist soil than for dry soil, due to the lubricant action of water on particles ([32], [35]).

Few studies about the impact of logging on soil have been conducted in Mediterranean countries (e.g., [41], [33]), which are among the most prone to erosion worldwide ([29], [14], [46]). Moreover, the studies on soil compaction and rutting in relation to the machine type (tracked vs. wheeled) showed contrasting results ([13]).

This study aims to evaluate the effects on soil compaction and rutting of wheeled and tracked tractors at two levels of soil moisture.

Materials and methods

Description of the study area

The study was carried out in the Rincine forest, a nature reserve 40 km northeast of Florence (central Italy). The mean annual precipitation in the period 2009-2013 was 1133 mm, with the maximum in November and the minimum in July. In the same period, the mean annual temperature and the means of the coldest and warmest months (January and July) were 9.2 °C, 1.5 °C and 17.8 °C, respectively. Soil developed on Lower Miocene-Oligocene sandstone and was classified as Dystric Cambisol based on the World Reference Base for Soil Resources ([26]).

The study site was a 30-years-old, even-aged plantation of Picea abies (L.) H. Karst, Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco, Abies alba (Mill.), and Chamaecyparis spp. located at 900 m a.s.l. on a 5-10% slope terrain. At the beginning of the experiment, the average duff thickness was measured on 60 points by a ruler with an accuracy of ± 0.5 mm. Particle size distribution was determined using the hydrometer method, as described in Gee & Bauder ([18]), on five samples of the top 30 cm of mineral soil, randomly distributed throughout the study area. Soil organic matter content was determined by loss on ignition ([22]) on fifteen samples.

Two tractors were used in our study, a tracked New Holland 88-85 (3908 cm3 displacement and 62.5 kW power) with an empty mass of 4600 kg and a wheeled New Holland T 4050 (4500 cm3 displacement and 71 kW power) with an empty mass of 4145 kg, equipped with power drive forestry (11.2-24.0) tires on the front axle and agroforest 410 (420/85-30) Trelleborg on the rear axle. Both types of tires had reinforced sidewalls and a cut-resistant rubber compound. Inflation pressures were 150 kPa and 100 kPa in the rear and front tires, respectively. To measure the contact area between the tire and the ground, we pulled a rope tightly around the portion of the tire on the ground, assuming a circular contact patch ([39]). The average contact pressure was determined to be 46 kPa and 54 kPa in the front and rear axles, respectively; they were assumed to be uniformly distributed over every point of the four contact areas.

Measurements of soil compaction and rutting were performed immediately before and after tractor passes. Since the aim was to investigate the effects of tracked and wheeled machines on soil disturbance, tractor passes were conducted without loads in order to avoid the impacts of the skidded logs on soil.

Experimental design and measurements

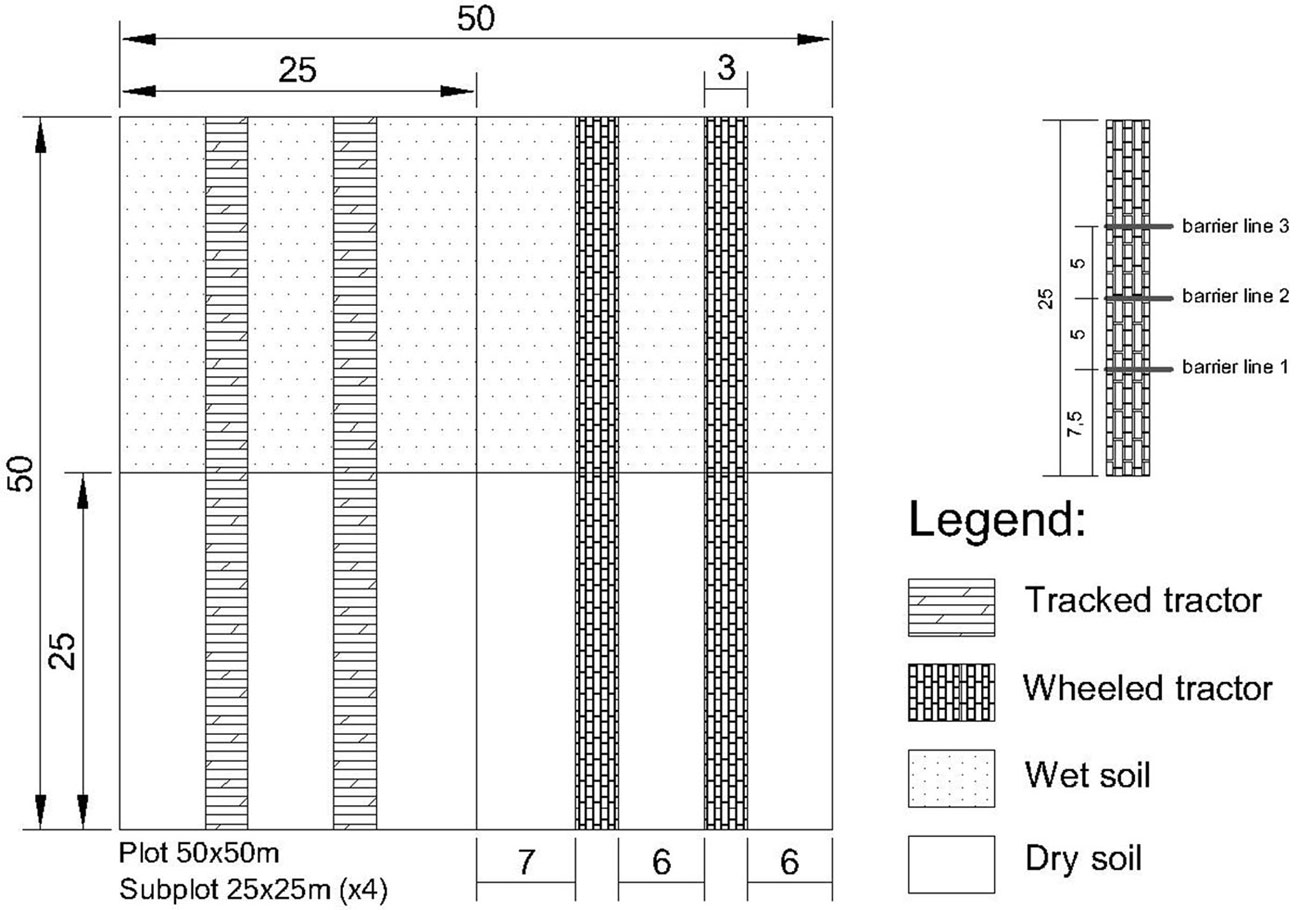

A split-plot design was applied to verify the impact of tractors on soil. Three 50 × 50 m areas were divided into four 25 × 25 m plots. Two skid trails were marked within each plot, resulting in a total of 24 trails per tractor (3 × 4 × 2 = 24). In each plot, one skid trail was trafficked with a tracked tractor and the other with a wheeled tractor. Half of all plots were trafficked when soil was relatively dry (11-13% soil moisture) and the other half when the soil was moister (24-25% soil moisture). Soil moisture was measured using a W.E.T. Sensor Kit (Delta-T Devices, Burwell, UK) at each sampling point. Treatments are hereafter called TD (tracked tractor on dry soil), TM (tracked tractor on moist soil), WD (wheeled tractor on dry soil), and WM (wheeled tractor on moist soil). Soil bulk density was measured after five tractor passes (one pass = one round trip), and rut depth was measured after one, three, and five passes. Five soil samples per skid trail and treatment - for a total of 30 (5 × 6) samples - were collected using a rigid metallic cylinder (8.5 cm height and 5.0 cm inner diameter) after litter removal to determine bulk density. Thirty additional samples were collected at a distance of 2 m from the tracks before the tractor had passed and were used as control or undisturbed soil. Soil samples were weighed in the lab before (“moist weight”) and after oven drying at 105 °C to constant weight (“dry weight”). Soil porosity (n) was determined by the following equation ([10] - eqn. 1 ):

where Dp is the particle density measured by a pycnometer (Multipycnometer, Quantachrome, Boynton Beach, FL, USA) on the same soil samples used to determine the bulk density (Db).

Penetration resistance and shear resistance were measured in triplicate close to each sampling point using a TONS/FT2 penetrometer and a GEONOR 72412 scissometer, respectively.

Three lines per skid trail were selected in order to evaluate the rutting (Fig. 1). The lines were orthogonal to the trail direction. On these lines, the distance between a horizontally leveled rod and the bottom of the rut was measured every 10 cm over the skid trail width section, both before trafficking and after one, three, and five passes of the tractor.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was carried out using the software package STATISTICA® ver. 7.1 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). All data were checked for normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test). One-way and two-way ANOVA and MANOVA analysis and a post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test were applied to assess the statistical differences between groups. The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to bulk density data because of their heteroscedasticity. A non- linear regression model was applied to determine the relationship between rut depth and the number of passes.

Results

The litter+duff layer was 3.5 ± 0.35 cm thick, while organic matter in the mineral soil averaged 106 g kg-1. Soil particle-size distribution fell in the loam region of the USDA triangle, the average values (± standard deviations) of coarse sand, medium sand, fine sand, silt, and clay being 135 ± 42 g kg-1, 94 ± 38 g kg-1, 280 ± 38 g kg-1, 389 ± 88 g kg-1, and 102 ± 21 g kg-1, respectively. In all treatments, bulk density, and shear and penetration resistances were significantly higher in the trafficked soil portions than in the undisturbed ones, while the opposite was true for porosity (Tab. 1). A significant statistical difference in bulk density was recorded between the WD and WM treatments. The lowest increase with respect to the control was recorded with WD (26%), while the highest increase was recorded with WM (33%). No significant differences were recorded among wheeled and tracked treatments at the same soil moisture. Soil porosity showed a significant reduction relative to the control due to traffic in both soil moisture conditions. A significant difference in soil porosity was recorded between WD and WM. Shear and penetration resistances showed the highest increase when the wheeled tractor was used on moist soil (403% and 50%, respectively) and the lowest increase when the tracked tractor was used on dry soil (211% and 28%, respectively). Shear resistance was significantly higher for all the treatments in comparison with the control and showed significant differences between both tractor types and soil moisture conditions. Penetration resistance showed significant differences for all treatments in comparison to the control and between WD and TD.

Tab. 1 - Soil moisture, bulk density, porosity, and shear and penetration resistances (mean ± standard deviation) of the skid trails after five passes and of the controls. Different letters show statistically significant differences among treatments after Tukey’s HSD tests (P < 0.05, N = 210). (CD): control in dry soil; (CM); control in moist soil; (WD): wheeled tractor on dry soil; (TD); tracked tractor on dry soil; (WM); wheeled tractor on moist soil; (TM): tracked tractor on moist soil.

| Treatment | Soil moisture (%) |

Bulk density (g cm -3 ) |

Porosity (%) |

Shear resistance (kPa) |

Penetration resistance (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | 11.98 ± 0.74 a | 0.72 ± 0.16 c | 73 ± 6 c | 21.51 ± 2.69 c | 0.29 ± 0.07 c |

| WD | 11.58 ± 0.66 a | 0.91 ± 0.02 b | 65 ± 6 b | 88.67 ± 5.60 a | 0.42 ± 0.06 a |

| TD | 12.37 ± 0.60 a | 0.97 ± 0.08 ab | 63 ± 3 ab | 66.87 ± 4.01 b | 0.37 ± 0.04 b |

| CM | 24.47 ± 0.80 b | 0.77 ± 0.11 c | 71 ± 4 c | 19.12 ± 4.95 c | 0.26 ± 0.05 c |

| WM | 24.34 ± 0.83 b | 1.02 ± 0.17 a | 62 ± 7 a | 96.27 ± 0.76 e | 0.39 ± 0.06 ab |

| TM | 24.60 ± 0.75 b | 0.98 ± 0.11 ab | 63 ± 4 ab | 80.25 ± 1.58 d | 0.40 ± 0.07 ab |

Concerning rutting, one single pass created deeper ruts in moist soil than in dry soil with both wheeled and tracked tractors (Tab. 2). Three passes deepened the ruts further. The average depth increment compared to one pass was significantly different only between WM and TD. After five passes, the average rut depth increment compared to three passes did not show statistical differences among treatments.

Tab. 2 - Results of the one-way MANOVA for rut depths (mean ± standard deviation, in cm) in relation to the number of tractor passes. Wilks test’s value: 0.86915, F[9] = 22.144, p = 0.02082. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments after Tukey’s HSD test (N = 144). (WD): wheeled tractor on dry soil; (TD): tracked tractor on dry soil; (WM): wheeled tractor on moist soil; (TM): tracked tractor on moist soil; (1): average depth increment compared to 1 pass; (2): average depth increment compared to 3 passes.

| Treatments | N | Av. depth (after 1 pass) |

Av. depth increment (after 3 passes) (1) |

Av. depth increment (after 5 passes) (2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WD | 36 | 1.51 ± 1.18 b | 0.85 ± 0.63 ab | 0.44 ± 0.47 |

| TD | 36 | 1.64 ± 2.88 b | 0.53 ± 0.30 a | 0.60 ± 0.72 |

| WM | 36 | 2.84 ± 1.77 a | 1.10 ± 0.82 b | 0.52 ± 0.43 |

| TM | 36 | 3.41 ± 6.32 a | 0.95 ± 0.97 ab | 0.56 ± 0.84 |

| p-level | - | < 0.05 | < 0.01 | > 0.05 |

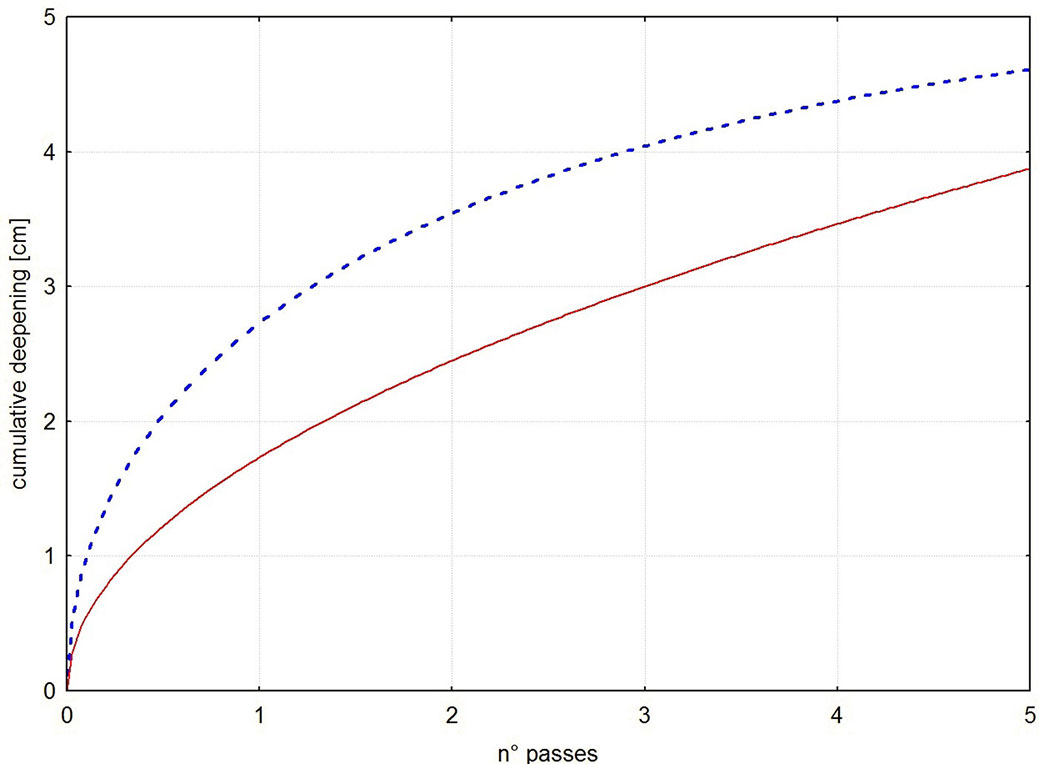

The regression curves between passes and rut depth in moist and dry soils were statistically significant (p < 0.01) for the wheeled tractor (Tab. 3 and Fig. 2). The fitted models explained approximately 50% and 47% of the variation in the cumulative rut depth per number of skidding cycles for the moist and dry soils, respectively.

Tab. 3 - Regression summary for: (i) wheeled tractor on moist soil (R2= 0.507, R2adjust = 0.500, F[2, 141] = 72.598, p < 0.01); and (ii) wheeled tractor on dry soil (R2= 0.478, R2 adjust = 0.471, F[2, 141] = 64.692, p<0.01). (SE): standard error.

| Group | Variable | Beta | SE | B | SE | t(141) | p-level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (i) | N° passes | -0.41682 | 0.209693 | -0.54195 | 0.272641 | -1.98776 | 0.048775 |

| (N° passes)0.5 | 1.102428 | 0.209693 | 3.272679 | 0.622495 | 5.25735 | 0.000001 | |

| (ii) | (N° passages)0.5 | 0.941042 | 0.215737 | 1.732946 | 0.397283 | 4.362 | 0.000025 |

Fig. 2 - Regression curves between cumulative deepening of ruts and the number of passes for the wheeled tractor treatment (dotted curve: moist soil condition; continuous curve: dry soil condition). Error bars were not shown for clarity. Regression parameters are reported in Tab. 3.

Discussion

The soil physical properties analyzed in this study (bulk density, porosity, and shear and penetration resistances) are generally assumed as the most representative for the assessment of the direct impact of vehicles on soil ([13]). Indeed, they largely affect the soil biota because of their influence on gas and solution exchanges ([7], [57]). The logging-induced increases in soil bulk density found in this study were similar to or larger than most values obtained with comparable machinery and soil textures (e.g., [36], [41], [35]).

Although the tracked tractor had lower ground contact pressure (35 kPa) than the wheeled tractor (46 kPa and 54 kPa in the front and rear tires, respectively), no significant differences were found between the impact of the two vehicles on soil bulk density and porosity. Similar results were obtained by Kamaruzaman ([27]) on a clay loam soil at the Berkelah Forest Reserve in central Pahang (Malaysia), and by Sheridan ([47]) on a silty clay loam forest soil at the Wombat State Forest, Victoria (Australia). Additional studies on the same topic reported contrasting results. Bashford et al. ([8]) and Rusanov ([43]) found that tracked tractors compacted the soil less than similar wheel tractors, while Spinelli et al. ([51]) and Jansson & Johansson ([32]) found that the use of a tracked machine resulted in a higher increase in bulk density, in spite of its lower ground pressure and a more scattered stand traffic.

Our finding may be explained by the behavior of tracks and tires. In fact, the power drive systems of tracked vehicles produce more vibrations and have longer loading time than wheeled vehicles, thus causing higher dynamic stresses to soil ([58], [60], [50]). In crawler vehicles, the peak values of ground pressure that cause soil stresses may be three times higher than the average values ([28], [58], [60], [59]).

The impact on soil bulk density and porosity by both tractors could have been partly mitigated by the duff layer, which reduces the wheel/track pressure on the mineral soil. Nonetheless, the values of soil bulk density and porosity we measured could imply some constraints to plant growth and forest regeneration ([53], [61]). In this regard, Heilman ([21]) found that root penetration of 35- to 45-day-old Pseudotsuga menziesii seedlings declined linearly with the increase in soil bulk density, although it was substantially prevented only beyond 1.74 Mg m-3.

The remarkable increase in soil shear resistance (200-400%), which occurred with both vehicles and was higher with higher soil moisture, can hinder root elongation and soil workability. Even a moderate increase in penetration resistance (28-54%) is an indicator of soil deterioration ([40], [16]), although much higher machinery-induced values were reported in the literature ([13]).

Shear resistance was significantly lower in the TD treatment than in the other treatments, suggesting that the tracked tractor used on relatively dry soils was the preferable approach to remove logs from this study site. Such a conclusion is not fully supported by the results of bulk density and penetration resistance, as they refer to different soil top layers (8.5 cm for bulk density, and only 2 cm for penetration resistance), while shear resistance was measured in the first 4 cm.

Overall, the impact of the tracked tractor on soil was scarcely influenced by the soil moisture, which on the contrary, significantly increased the impact of the wheeled tractor. In particular, soil became more prone to rutting with increasing soil moisture. We conclude that wheeled tractors should be used only when soil moisture is low; crews should wait for one or more days after the last rainfall event if possible, depending on soil texture. In this study, measurements were carried out one week after the last rainfall; however, one single tractor pass was enough to cause rut formation on the skid trail. We also assessed that such impact of both tractors increased significantly with few additional passes, confirming the findings of other studies ([38], [47], [17], [2], [49]).

Conclusions

Our study showed that basic physical properties of a loam forest soil - bulk density, porosity, and shear and penetration resistances - were significantly modified by few tractor passes. The extent of such modifications depended on the type of tractor and soil moisture. Tractor passes (one to five) clearly affected rut depth, though the average rut depth increment decreased with the number of passes. Deep ruts occurred in moist soil with just a single pass. The largest negative impact on soil occurred when using the wheeled tractor on moist soil. In this case, however, the post-harvest soil bulk density and penetration resistance did not reach values potentially harmful to stand productivity and regeneration. Using the tracked tractor on dry soil minimized the impact, especially in terms of shear and penetration resistances.

Based on the above considerations, it is highly recommended to wait for soil to be as much dry as possible before skidding. Moreover, the use of tracked tractors in wet conditions is preferable in terms of soil conservation. Further research performed across a wider range of soil types and logging systems is needed to obtain a more comprehensive insight on this topic.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the Union of Mountain Municipalities of Valdarno and Valdisieve, in particular to Dr. Antonio Ventre and Dr. Iacopo Battaglini, managers of the Rincine forest, for performing the thinning and other related operations according to our recommendations.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Fabio Fabiano

Cristiano Foderi

Andrea Laschi

Dipartimento di Gestione dei Sistemi Agrari, Alimentari e Forestali (GESAAF), Università di Firenze. v. S. Bonaventura 13, I-50145 Firenze (Italy)

Dipartimento di Scienze delle Produzioni Agroalimentari e dell’Ambiente (DISPAA), Università di Firenze. p.le delle Cascine 18, I-50144 Firenze (Italy)

Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie per l’Agricoltura, le Foreste, la Natura e l’Energia (DAFNE), Università della Tuscia, v. San Camillo De Lellis, I-01100 Viterbo (Italy)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Cambi M, Certini G, Fabiano F, Foderi C, Laschi A, Picchio R (2015). Impact of wheeled and tracked tractors on soil physical properties in a mixed conifer stand. iForest 9: 89-94. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1382-008

Academic Editor

Elena Paoletti

Paper history

Received: Jun 20, 2014

Accepted: Jan 31, 2015

First online: May 22, 2015

Publication Date: Feb 21, 2016

Publication Time: 3.70 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2015

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 60991

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 48162

Abstract Page Views: 5334

PDF Downloads: 6025

Citation/Reference Downloads: 33

XML Downloads: 1437

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 3939

Overall contacts: 60991

Avg. contacts per week: 108.39

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2016): 54

Average cites per year: 5.40

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Short-term recovery of fine root carbon stock is inhibited by skid trails in a humid tropical forest

vol. 18, pp. 344-349 (online: 30 November 2025)

Research Articles

The natural recovery of disturbed soil, plant cover and trees after clear-cutting in the boreal forests, Russia

vol. 13, pp. 531-540 (online: 18 November 2020)

Research Articles

Short-term effects in canopy gap area on the recovery of compacted soil caused by forest harvesting in old-growth Oriental beech (Fagus orientalis Lipsky) stands

vol. 14, pp. 370-377 (online: 10 August 2021)

Research Articles

Use of terrestrial laser scanning to evaluate the spatial distribution of soil disturbance by skidding operations

vol. 8, pp. 386-393 (online: 08 October 2014)

Research Articles

Effects on soil physicochemical properties and seedling growth in mixed high forests caused by cable skidder traffic

vol. 16, pp. 127-135 (online: 23 April 2023)

Research Articles

Estimating machine impact on strip roads via close-range photogrammetry and soil parameters: a case study in central Italy

vol. 11, pp. 148-154 (online: 07 February 2018)

Research Articles

Use of LIDAR-based digital terrain model and single tree segmentation data for optimal forest skid trail network

vol. 8, pp. 661-667 (online: 22 December 2014)

Research Articles

Influence of slope on physical soil disturbance due to farm tractor forwarding in a Hyrcanian forest of northern Iran

vol. 7, pp. 342-348 (online: 17 April 2014)

Research Articles

Effects of soil compaction on seedling morphology, growth, and architecture of chestnut-leaved oak (Quercus castaneifolia)

vol. 10, pp. 145-153 (online: 13 June 2016)

Research Articles

Assessment of timber extraction distance and skid road network in steep karst terrain

vol. 10, pp. 886-894 (online: 06 November 2017)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword