Drought tolerance in cork oak is associated with low leaf stomatal and hydraulic conductances

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 11, Issue 6, Pages 728-733 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor2749-011

Published: Nov 06, 2018 - Copyright © 2018 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

To investigate the role of seeds origin in drought tolerance, the response to water deprivation of cork oak seedlings differing in climatic conditions at their geographical origin was compared. Gafour is the provenance from the driest site and Feija is the provenance from the wettest site. Net photosynthesis (An), stomatal conductance (gs) and leaf water potential were measured during dehydration. A delayed decrease in leaf water potential is observed after water withholding in Gafour as compared to Feija leaves. At the onset of dehydration, An and gs were higher in Feija. After withholding watering, Gafour leaves were able to maintain a higher An and gs than Feija leaves. Most likely, drought tolerance in Gafour leaves is associated to their lower gs under well-hydrated conditions. The stomatal density (Ds) and specific leaf area (SLA) were not different in well-watered leaves but, leaf hydraulic conductance was lower in Gafour leaves when compared to Feija leaves. Our results suggested that lower stomatal and hydraulic conductances of Gafour leaves could be involved in bringing about the better resistance to dehydration.

Keywords

Drought, Cork Oak, Photosynthesis, Stomatal Conductance, Hydraulic Conductance

Introduction

Drought is one of the main factors limiting plant growth and production of ecosystems in many parts of the world ([42]). Water stress significantly alters plant metabolism ([36]) and profoundly affects agriculture ([31]). A better understanding of the mechanisms that allow plants to survive during a prolonged drought would help to select more drought-tolerant genotypes by identifying traits associated with drought resistance ([24]). Indeed, acclimation to drought is the result of integration of several events, ranging from the perception and transduction of the stress signal to the regulation of gene expression and metabolic changes ([41]). Water stress is established in terrestrial plants when the water loss by leaves exceeds that absorbed from the environment by their roots ([34]). Therefore, relative water content (RWC), water potential (Ψ) and cells turgor are reduced, while concentrations of compatible osmolytes as amino acids and sugars increase, leading to decrease of osmotic potential ([19]). When water limitation is imposed, plants develop a series of responses at the cellular and molecular levels ([6]). The stomata are gradually closed decreasing the conductance to water vapor diffusion which slows down the transpiration and the rate at which the water deficiency develops ([21]).

In addition, carbon photosynthetic assimilation often decreases concomitantly with decreased conductance to CO2 diffusion ([22]). There is a controversy over the mechanisms by which photosynthetic activity is diminished under water stress. Stomatal closure is probably the major factor controlling photosynthesis, but the relative role of stomatal limitation on photosynthesis depends on the severity of water deficiency.

The Mediterranean climate is defined by a dry and warm summer. The period of summer drought is increasingly intensified and prolonged due to climatic change effects. Forests are known as highly sensitive to climate change due to the lack of trees adaptive responses to environmental fluctuations. Thereby, forests adaptation strategies should be able to anticipate the expected change. In fact, forests will have to face environmental conditions which are becoming increasingly severe for many decades, even more than a century. Climate changes will have various impacts on forests from different bioclimatic regions, and on the globally distribution of tree species. It seems difficult to predict the impact of climate change without a better understanding of the effect of atmospheric CO2 rising and drought.

Cork oak (Quercus suber L.) is a sclerophyllous, evergreen Mediterranean tree species adapted to long dry summer conditions with little or no precipitation, maximum temperatures reaching 35-40 °C, and irradiance exceeding 2000 µmol m-2 s-1 at midday. Previous studies show an intraspecific variability between different Tunisian cork oak provenance differing by their ecology in response to summer drought ([3]), seasonal variations of leaf gas exchange parameters ([27], [3]), and light growth ([32], [33]).

In the present study, we have examined how geographical origin of seeds might affect early responses to drought stress in cork oak seedlings.

Materials and methods

Plant material and drought experiments

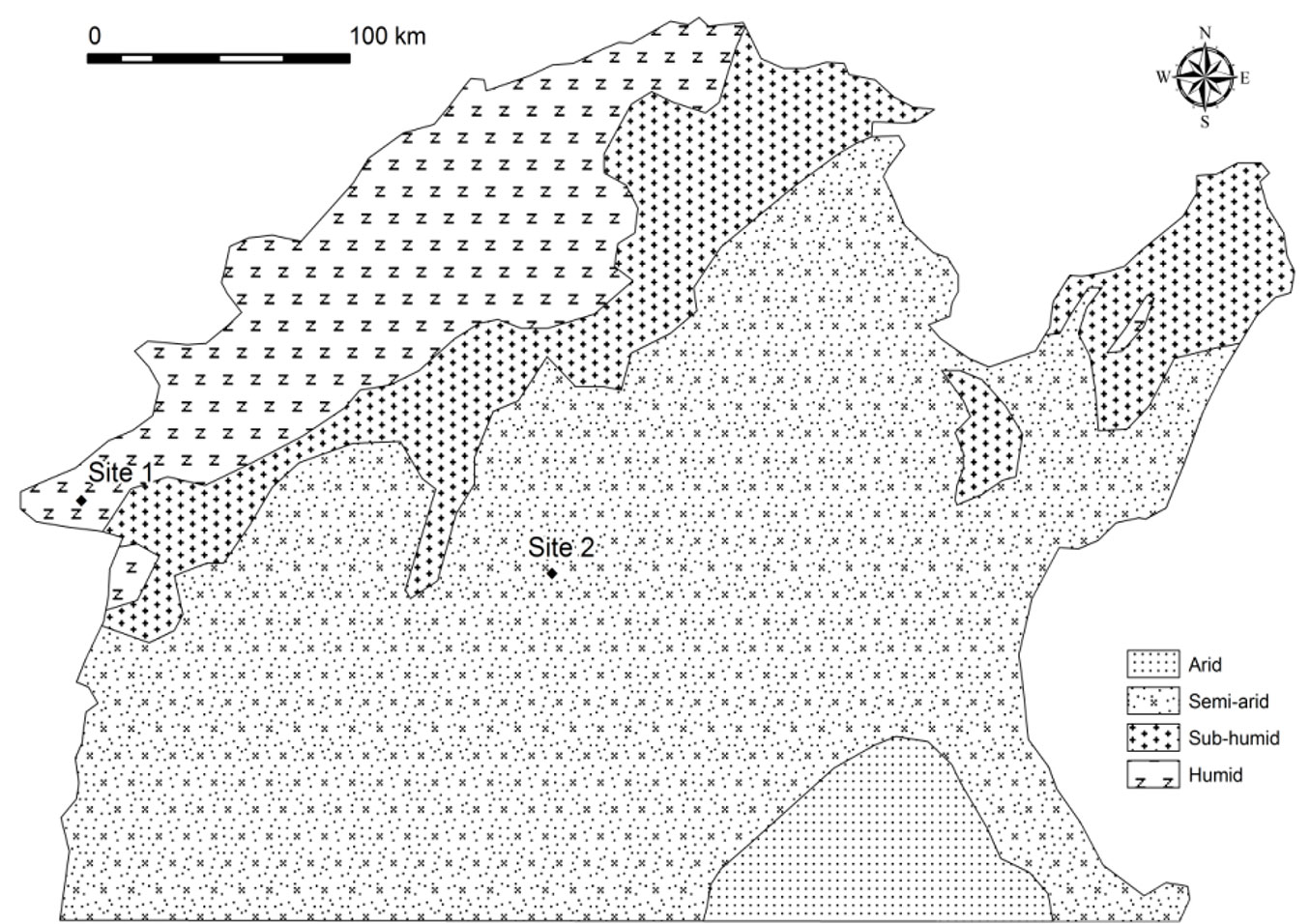

Acorns were collected from two populations originating from contrasting environments in the northwestern provinces of Tunisia (Fig. 1), as described in Rzigui et al. ([33]). The first site, the National Park of Feija (36° 30′ 00″ N, 8° 20′ 00″ E), is located in the northern extent of the Kroumirie mountains and is characterized by a cold and humid climate. The average of temperature is 7 °C in January and can drop to 0 °C, which allows for year round snowfall. The second site is located at Gafour (36° 32′ 19″ N, 9° 32′ 40″ E) in the southern hills and plains around Siliana, and it is characterized by a semiarid climate with moderate winters and hot dry summers.

Immediately after collection, acorns were planted in the greenhouse of the National Research Institute for Rural Engineering, Waters, and Forestry in Tunis under low light conditions (15% of full sunlight). Seedlings had been grown in 5 L pots containing a mixture of equal parts of soil and compost. During spring 2016, when the two provenances (five year-old seedlings) had similar shoot and leaf sizes, seedlings were used for drought experiments. Drought was imposed by withholding watering. Gas exchange was measured at the onset of experiment and at 3, 7, 14 and 17 days after withholding water. The same plants were used at the five measuring times. All experiments were carried out using fully expanded and developed leaves.

Leaf water potential measurement

Measurements of water potential (ψleaf, MPa) were made directly after completing the An and gs measurements. Leaves were rapidly pressurized (within 15 s) with nitrogen. We have used a Scholander-type pressure chamber (SKPM 1400®, Skye Instruments Ltd., Powys, UK).

Gas exchange measurements

Gas exchange measurements were carried out on attached intact leaves using a Licor 6400® (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA). Leaf temperature was maintained at 25 °C, photon flux density at 1200 µmol m-2 s-1, ambient CO2 molar ratio (Ca) at 400 ppm and leaf vapour pressure deficit at around 1 kPa.

Specific leaf area determination

The specific leaf area (SLA) was determined as the ratio of the leaf area (measured using a leaf area meter, Portable Laser, Model Cl-202) to leaf dry mass of individual leaves.

Stomatal density determination

Imprints from fully developed Feija and Gafour leaves were made by coating the adaxial surface with clear nail varnish. After a few minutes, the varnish was gently peeled off the leaves and then leaf stomatal density, expressed as the number of stomata per unit leaf area, was determined using a light microscope (Leica M205 C, Wetzlar, Germany) at a magnification of 400×. Stomata counting and measuring was conducted on at least three randomized visual areas on each leaf surface.

Leaf hydraulic conductance measurement

Leaf hydraulic conductance on a surface area basis (Kleaf, mmol s-1 m-2 MPa-1) was measured with XYL’EM® apparatus (Bronkhorst, Ruurlo, Netherlands) as described by Cochard et al. ([7]). The principle was to measure the water flow (F, mmol s-1) entering the petiole of a cut leaf when exposed to positive pressure (+P, MPa). Upon steady state, Kleaf was computed as (eqn. 1):

where LA is the total leaf area (m2). The XYL’EM was interfaced with a computer to log different data automatically.

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements

In vivo chlorophyll a fluorescence emissions in 30-min dark-adapted leaves were measured with a portable modulated chlorophyll fluorometer (OS-30p+®, Opti-Sciences, Hudson, NH, USA) at predawn and midday. After adaptation to the darkness, the modulated fluorometer allows the accurate measurement of minimum fluorescence (Fo) using a weak, modulated light that is too low to induce photosynthesis. In this state, photosystem II is maximally oxidized. A subsequent saturating flash of white light (3500 μmols) reduces all available PSII reaction centers, and the maximum fluorescence (Fm) during the saturating light radiation is recorded. The maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII was calculated as the ratio of the light-induced variable and maximum fluorescence of chlorophyll, Fv/Fm (eqn. 2):

Photosynthetic pigments

Leaf tissue of known area (measured using a leaf area meter, Portable Laser, Model Cl-202) and fresh weight was incubated in 80% acetone until all of the chlorophyll was visibly extracted. Spectrophotometer readings of the extracts were obtained at 750, 663, 645 and 453 nm to determine the chlorophyll a and b and total carotenoid contents using the equations of Arnon ([2]). Chlorophyll and carotenoid concentrations were estimated on the basis of fresh weight and leaf area.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were repeated independently at least for three times and mean values and the standard errors are shown. Significant statistical differences at the level 5% were calculated with the Student’s t-test using the software Sigma Plot® (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Two-way analysis of variance was also conducted to test the interaction effect (provenance × time) on net photosynthesis rate (An) and stomatal conductance (gs).

Results

It was possible to apply the dehydration treatment to the two provenances at a similar developmental stage. At the onset of the drought, Gafour and Feija well-watered plants (-0.5 and -0.7 MPa of ψleaf) had the same foliar evaporative surfaces ([25]). Specific leaf area (SLA) and the total chlorophyll concentration on the basis of leaf area were similar in both provenances (Tab. 1).

Tab. 1 - Physiological properties of well-watered Feija and Gafour seedlings at the onset of experiment: net photosynthesis (An, μmol m-2 s-1); stomatal conductance (gs, mmol m-2 s-1); leaf hydraulic conductance (Kleaf); stomatal density (Ds, pores mm-2); and total chlorophyll (mg m-2). Significant differences (P < 0.05) between WT and CMSII leaves are indicated by different letters.

| Parameters | Feija | Gafour |

|---|---|---|

| An (μmol m-2 s-1) | 12.9 ± 0.5 a | 10.4 ± 0.7 b |

| gs (mol m-2 s-1) | 0.3 ± 0.04 a | 0.2 ± 0.01 b |

| Kleaf (mmol s-1 m-2 MPa-1) | 7.1 ± 1.2 a | 4.9 ± 0.5 b |

| Ds (pores mm-2) | 282.6 ± 24 a | 285.0 ± 20 a |

| Total chlorophyll (mg m-2) | 395.7 ± 36 a | 362.7 ± 39 a |

| SLA (cm2 g-1) | 126.0 ± 15 a | 125.0 ± 9 a |

On the other hand, stomatal conductance (gs) and net CO2 uptake (An) were lower in Gafour leaves (Tab. 1). Stomatal density was similar in both provenances (Tab. 1), while leaf hydraulic conductance (Kleaf) was higher in Feija leaves (Tab. 1).

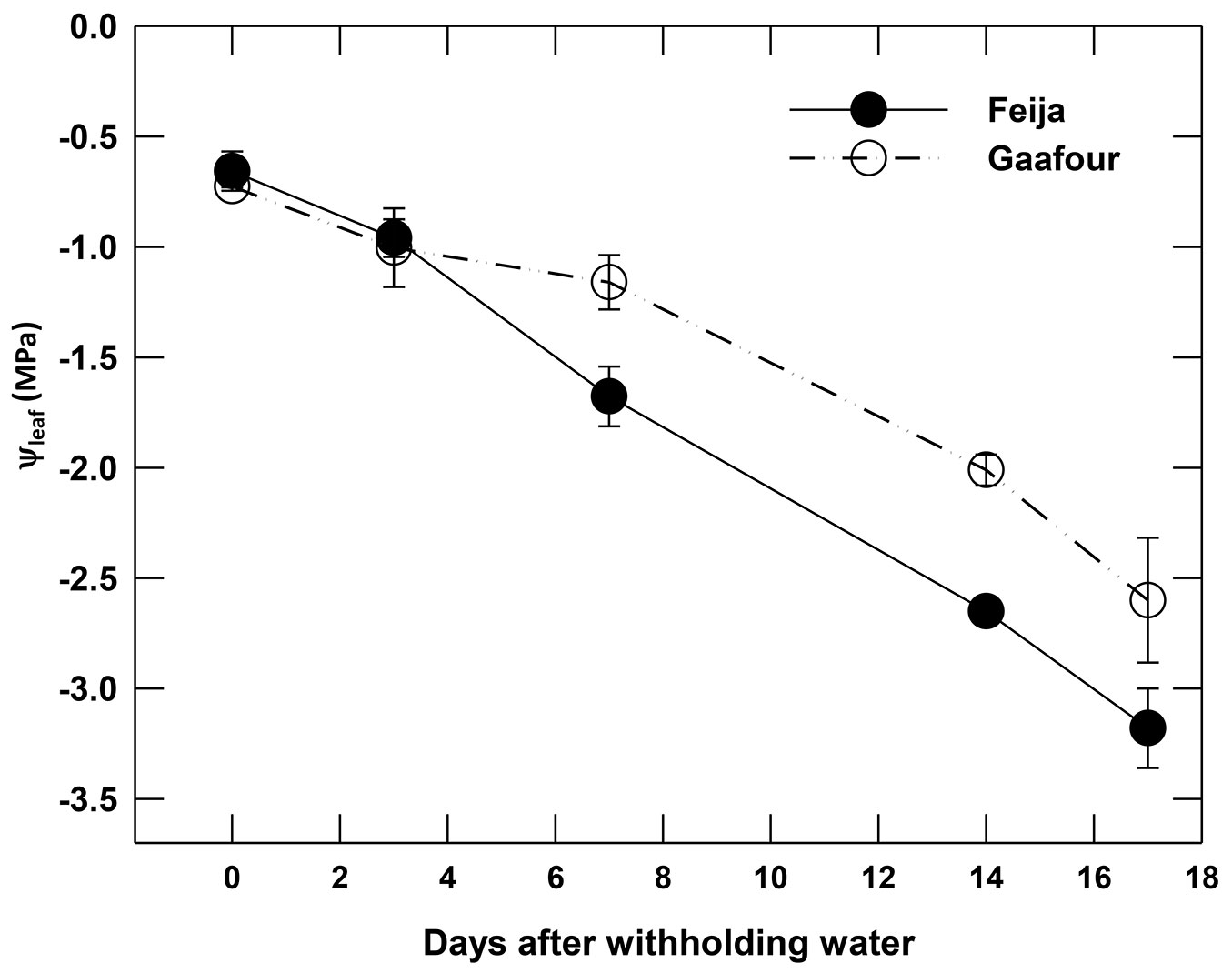

After withholding watering, Gafour plants maintained a higher leaf water potential than Feija plants (Fig. 2). After 14 days of drought, leaf water potential was reduced by 76% and 64% in Feija and Gafour seedlings, respectively.

Fig. 2 - Leaf water potential (ψleaf, MPa) as a function of time after withholding watering. Data are mean ± SE of four independent measurements.

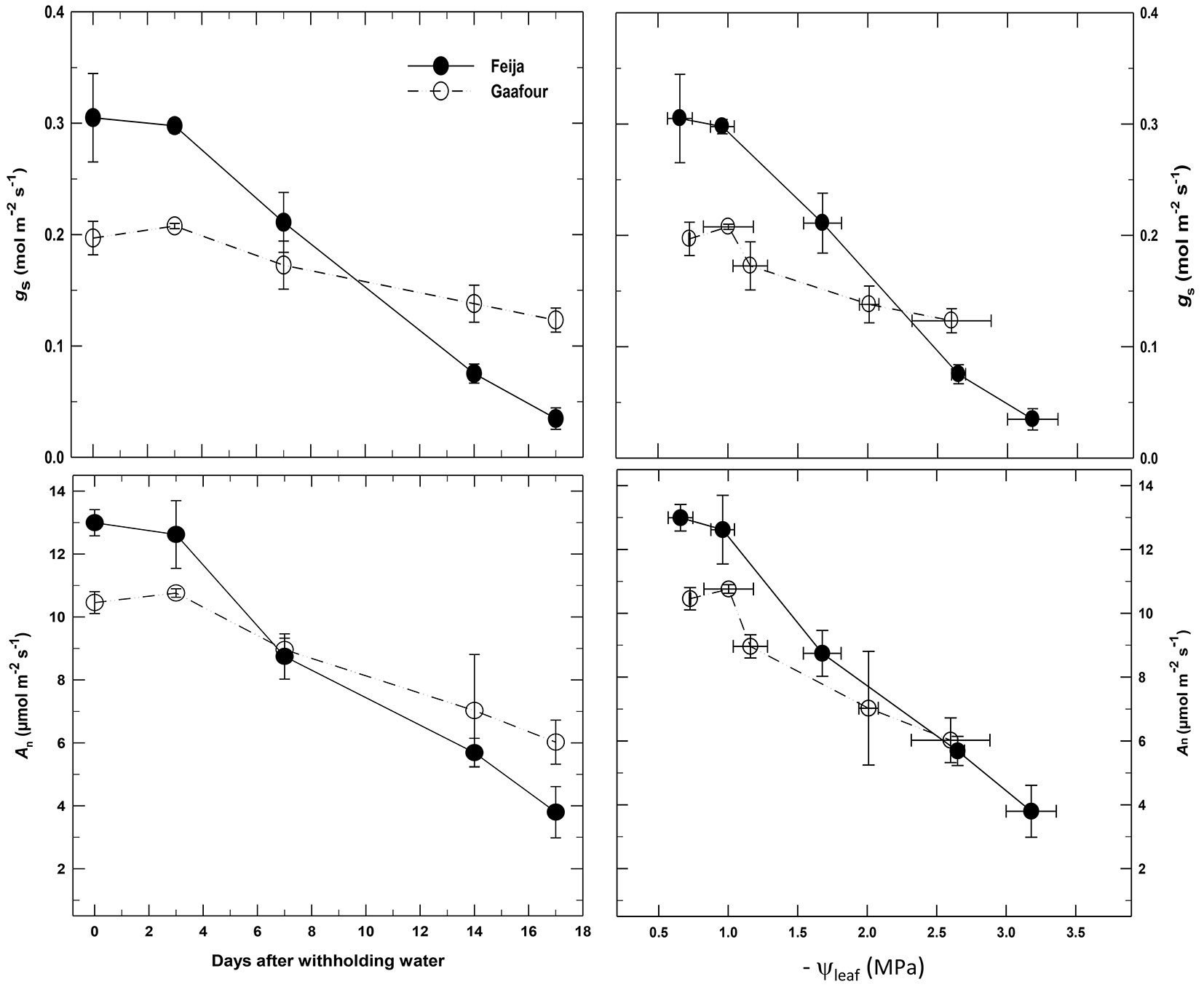

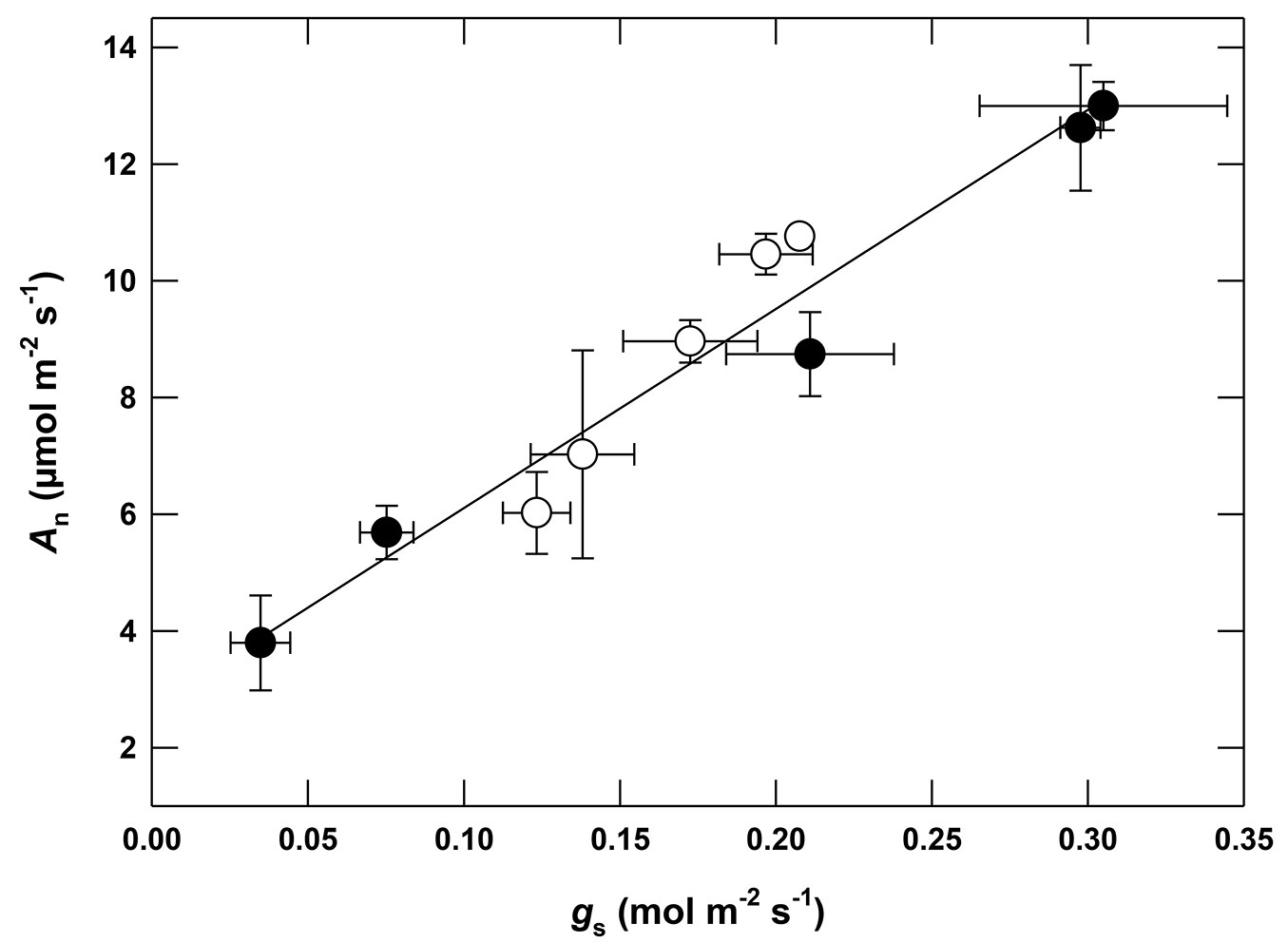

Withholding watering caused a slower decrease of gs in Gafour leaves (Fig. 3). As a result, gs was higher in Gafour leaves than in those of Feija after 10 days. The trend followed by An during drought treatment was similar to gs (Fig. 3). There is a statistically significant interaction (Tab. 2) between provenance and measuring time on both gs (p <0.001) and on An (p <0.05). The relation between An and gs was the same for Feija and Gafour leaves (Fig. 4). However, both gs and An were lower in Gafour at ψleaf ranging between -0.5 and -2.5MPa, as compared to Feija seedlings (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 - Stomatal conductance (gs) and net CO2 uptake (An) as a function of time after withholding watering and leaf water potential. Conditions: leaf temperature 25 °C; vapour pressure deficit (VPD) 1 ± 0.2 kPa; photon flux density (PFD) 1200 µmol m-2 s-1. Data are mean ± SE of four independent measurements.

Tab. 2 - Summary of two-way analysis of variance (F-values) for differences in net photosynthesis rate (An) and stomatal conductance (gs) between measuring times and provenances. (ns): non-significant; (**): p < 0.01; (*): p <0.05.

| Factors | A n | g s |

|---|---|---|

| Provenance | 0.0731ns | 28.710** |

| Measuring time | 38.194** | 70.675** |

| Provenance × Measuring time | 4.241* | 37.981** |

The maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII (given by Fv/Fm in dark-adapted leaves) remained constant at approximately 0.8 during drought (measured at 0, 7 and 17 days after withholding watering) in both Feija and Gafour leaves (data not shown).

Discussion

Intraspecific differences in response to the drought

This study showed that intraspecific variability within a species changes the tolerance for water stress. Indeed, the leaf water potential of Gafour leaves exhibited a slower decrease than in Feija after a water withholding. In previous studies ([37], [16], [38]), this variability in response to drought has been investigated mainly between Mediterranean species (interspecific variability). In these species, photosynthesis has been shown to be essentially limited by stomatal closure ([38]) and more specifically by the concentration of CO2 at the catalytic sites of Rubisco ([16]). The interpopulation variability of the response to environmental constraints, including drought, has also been studied in many species. In cork oak, some studies have investigated intra-specific variability as a source of adaptation to different regional climatic conditions. For example, Ramirez-Valiente et al. ([28], [29]) analyzed phenotypic plasticity and local adaptation of foliar ecophysiological parameters in European populations subjected to different levels of water availability. In Tunisia, Staudt et al. ([35]) examined the release of volatile organic compounds during drought in Tunisian cork oak populations from contrasting climatic conditions. More recently, Rzigui et al. ([32], [33]) used seedlings from Feija and Gafour provenances to show the intra-specific variability of cork oak in response to high light. Several studies examined the intraspecific variability in the Tunisian cork oak forest, mainly concerning the seasonal variability of gas exchange ([27], [3]). These studies have also shown that the response of photosynthetic capacity to summer drought was different among trees of three populations of cork oak belonging to different habitats. Results of the present study showed that plants from two different regions with different ecological conditions do not have the same response to dehydration by stopping watering. The analysis of light response of different populations of Quercus coccifera from different localities, led to the conclusion that there is an ecotypical differentiation rather than a phenotypic plasticity ([4]). In this sense, Ramírez-Valiente et al. ([29]) showed that the variability of the present cork oak distribution is correlated with a variability of morphological and biochemical properties (SLA, nitrogen content, water use efficiency) of leaves. Current results indicate a variation in the plasticity of the provenances of Quercus suber in response to watering arrest. Indeed, two response types were distinguished in the studied provenances. For Feija provenance, a very rapid and simultaneous decrease of An and gs was registered. In contrast, this decrease was slower in seedlings of the Gafour provenance. Recently, Ramírez-Valiente et al. ([30]) have found that climatic origins of eleven Quercus virginiana populations induced variations in photoprotective pigments (anthocyanin and xantophyll cycle pigments) in response to temperature and drought.

The drought tolerance is associated to lower stomatal conductance (gs) under well-hydrated conditions

The delayed water loss in Gafour compared to Feija seedlings was not the result of a smaller transpiring leaf surface, since the total leaf surface of the plants at the beginning of the experiment were similar in both provenances ([25]). Water loss is delayed in Gafour leaves due to their lower stomatal conductance (gs) at the onset of the drought treatment and during the first days of the drought period (Fig. 2). It is obvious that the higher levels of stomatal conductance and net photosynthesis after 10 days of water withholding in Gafour leaves was related to their capacity to maintain their water potential and not to a differential response to a lack of water, because gs and An were lower in Gafour than in Feija leaves (Fig. 2) within the range -0.5 to -2.5 MPa of Ψleaf. Furthermore, Gafour and Feija seedlings were similarly affected by drought as indicated by identical relations between An and gs (Fig. 4). Thus, when compared to Feija, the plants of Gafour provenance were able to maintain a higher photosynthetic activity during the first days of dehydration conditions.

Hydraulic conductance is lower in Gafour plants under well hydrated conditions

As suggested by previous studies ([40], [20], [43]), the low gs in Gafour may be a consequence of low leaf stomatal density (Ds). However, contrary to expectation, Ds was similar in both provenances (Tab. 1), and the difference of gs between well watered plants recorded in this study is probably a consequence of a difference in stomatal aperture level. This is in accordance with Marenco et al. ([26]) which shown that, in six forest tree species of central Amazonia, gs did not increase with increasing Ds, and concluded that the aperture of the stomatal pores was below its maximum width. The opening and closing of stomata are strongly and finely regulated by many signaling factors ([23]), the most important are the abscisic acid (ABA) and hydraulic factors ([8]), which were acting in interaction. ABA interacts with so many processes, outside and inside the guard cell, that it is difficult to assess its importance by just measuring total leaf ABA content ([39]).

In the case of this study, leaf hydraulic conductance (Kleaf) was lower in Gafour plants, and it could be critical in setting the maximum possible gs. Indeed, it has been shown that Kleaf is strongly related to gs, indicating that there is an internal leaf-level regulation of liquid and vapour conductances ([5]). In leaf hydraulic system, the stomata are placed in series with the xylem. Since stomata control both CO2 and water vapor exchanges between the leaf and its environment, it is expected that the values of hydraulic conductance will be related to those of gs and the assimilation of CO2 ([11]). It could be that the lowest gs in Gafour leaves result from its lower Kleaf.

Inhibition of An depends on gs during dehydration

The decrease of An and gs as a function of the dehydration is faster in Feija than Gafour plants. For all Ψleaf ≥ -2 MPa, An and gs are higher in Feija as compared to Gafour plants. However, this difference disappears with Ψleaf below -2MPa. The relationship between An and gs is similar in both provenances, showing that the decrease in gs is the main factor of photosynthesis inhibition during dehydration as previously reported ([9], [10], [14]). This does not eliminate the possibility of non-stomatal limitation of photosynthesis. However, water stress may reduce leaf net photosynthetic assimilation (An) by both stomatal and metabolic limitations ([13]). In addition, many studies have reported that stomatal effects are major under moderate stresses, but biochemical limitations are quantitatively important during leaf ageing or during severe drought ([18], [15]). The maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII (given by Fv/Fm in dark-adapted leaves) in both Feija and Gafour leaves remained constant during the drought experiment. Cork oak, a widely distributed forest tree species in the Mediterranean basin, is able to maintain maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII during periods of drought ([12]). Additionally, Ghouil et al. ([17]) demonstrated its tolerance to high temperatures.

In conclusion, previous studies ([1], [29]) showed a large provenance-level differentiation in cork oak, with provenance from dry places exhibiting the higher tolerance. A distinct difference was observed in response to drought stress between both studied provenances (Gafour and Feija). The presented results show that Gafour seedlings exhibited lower stomatal and hydraulic conductances and a better tolerance to water deprivation. These physiological changes are likely to be the consequence of divergences between populations with respect to phenotypic plasticity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Institute for Rural Engineering, Waters, and Forestry in Tunis, Tunisia. We wish to thank Dr. Wahbi Djebali (Laboratory of Plant Toxicology and Environmental Microbiology, faculty of Sciences of Bizerte, University of Carthage, Tunisia), Dr. Soulwene Kouki (Laboratory of Water, Membranes and Environmental Biotechnologies, Centre of Water Research and Technologies, Tunisia) and Dr. Ichrak Jaouadi (Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University El Manar, Tunisia) for carefully reading the manuscript.

References

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Latifa Jazzar

Ben Baaziz Khaoula

Sondes Fkiri

Zouheir Nasr

Laboratoire de Gestion et de Valorisation de Produits Forestiers (LGVPF), Institut National de Recherche en Génie Rural, Eaux et Forêts (INRGREF), Tunis (Tunisia)

Institut Sylvo-pastoral de Tabarka, Université de Jendouba, Tabarka (Tunisia)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Rzigui T, Jazzar L, Baaziz Khaoula B, Fkiri S, Nasr Z (2018). Drought tolerance in cork oak is associated with low leaf stomatal and hydraulic conductances. iForest 11: 728-733. - doi: 10.3832/ifor2749-011

Academic Editor

Claudia Cocozza

Paper history

Received: Feb 02, 2018

Accepted: Aug 21, 2018

First online: Nov 06, 2018

Publication Date: Dec 31, 2018

Publication Time: 2.57 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2018

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 46767

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 38286

Abstract Page Views: 3873

PDF Downloads: 3552

Citation/Reference Downloads: 10

XML Downloads: 1046

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 2684

Overall contacts: 46767

Avg. contacts per week: 121.97

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2018): 8

Average cites per year: 1.00

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Light acclimation of leaf gas exchange in two Tunisian cork oak populations from contrasting environmental conditions

vol. 8, pp. 700-706 (online: 08 January 2015)

Research Articles

Developing stand transpiration model relating canopy conductance to stand sapwood area in a Korean pine plantation

vol. 14, pp. 186-194 (online: 14 April 2021)

Research Articles

Role of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance on the long-term rising of intrinsic water use efficiency in dominant trees in three old-growth forests in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro

vol. 14, pp. 53-60 (online: 28 January 2021)

Research Articles

Testing a dual isotope model to track carbon and water gas exchanges in a Mediterranean forest

vol. 2, pp. 59-66 (online: 18 March 2009)

Research Articles

Gas exchange characteristics of the hybrid Azadirachta indica × Melia azedarach

vol. 8, pp. 431-437 (online: 17 December 2014)

Research Articles

Stomatal morphometry of Andean species and their relationship with spatial variation

vol. 18, pp. 327-334 (online: 03 November 2025)

Research Articles

A comparison between stomatal ozone uptake and AOT40 of deciduous trees in Japan

vol. 4, pp. 128-135 (online: 01 June 2011)

Research Articles

Magnolia grandiflora L. shows better responses to drought than Magnolia × soulangeana in urban environment

vol. 13, pp. 575-583 (online: 07 December 2020)

Research Articles

A new approach to ozone plant fumigation: The Web-O3-Fumigation. Isoprene response to a gradient of ozone stress in leaves of Quercus pubescens

vol. 1, pp. 22-26 (online: 28 February 2008)

Research Articles

Adjustment of photosynthetic carbon assimilation to higher growth irradiance in three-year-old seedlings of two Tunisian provenances of Cork Oak (Quercus suber L.)

vol. 10, pp. 618-624 (online: 17 May 2017)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword