Thinning effects on soil and microbial respiration in a coppice-originated Carpinus betulus L. stand in Turkey

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 9, Issue 5, Pages 783-790 (2016)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1810-009

Published: May 29, 2016 - Copyright © 2016 SISEF

Research Articles

Collection/Special Issue: IUFRO division 8.02 - Mendel University Brno (Czech Republic) 2015

Coppice forests: past, present and future

Guest Editors: Tomas Vrska, Renzo Motta, Alex Mosseler

Abstract

Effects of thinning on soil respiration and microbial respiration were examined over a 2-year period (2010-2012) in a coppice-originated European hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.) stand in Istanbul, Turkey. Four plots within the stand were selected; tree density was reduced by 50% of the basal area in two plots (thinning treatment), and the other two plots served as controls. The study focused on the main factors that affect soil respiration (RS) and microbial respiration on the forest floor (RFFM) and in soil (RSM): soil temperature (TS), soil moisture (MS), soil carbon (C), soil nitrogen (N), soil pH, ground cover biomass (GC), forest floor mass (FF), forest floor carbon (FFC) and nitrogen (FFN), and fine root biomass (FRB). Every 2 months, soil respiration was measured using the soda-lime method, and microbial respiration was measured with the incubation method separately for the soil and forest floor. Results were evaluated yearly and over the 2-year research period. During the first year after treatment, RS was significantly higher (11%) in the thinned plots (1.76 g C m-2 d-1) than in the controls (1.59 g C m-2 d-1). However, there were no significant differences in either the second year or the 2-year study period. In the thinned plots during the research period, RS was linearly correlated with GC, Ts and FRB. Thinning treatments did not affect RSM, but interestingly, they did affect RFFM, which was greater in the control plots than in the thinned plots. RSM had a significant and positive correlation with soil N and soil pH, while RFFM was linearly correlated with FFC and C/N ratio of the forest floor in both thinned and control plots during the research period.

Keywords

CO2 Flux, Fine Root, Forest Floor, Ground Cover, Soil Temperature, Soil Moisture

Introduction

Accumulation and distribution of the soil carbon pools in forest ecosystems play a crucial role in the carbon cycle of terrestrial ecosystems and climate change, and underground ecological processes critically affect and regulate global soil carbon cycle dynamics ([55]). Soil respiration is one of the main terrestrial contributors to CO2 fluxes in the global carbon cycle ([15]). Thus, knowledge about soil respiration (both heterotrophic and autotrophic) is important for understanding terrestrial C cycling and feedback with regard to climate change ([13]).

In addition to temporal and spatial changes based on natural factors, forest operations can affect soil respiration and soil carbon pools. Understanding the effects of forest treatments on forest ecosystems is critical for estimating temporal carbon dynamics ([43]). The consequences of forestry practices on C balances and CO2 emissions from the soil are still poorly understood in terms of their impact on global C flux.

Forest thinning affects soil processes by altering key microclimatic conditions, root and microbial respiration, soil organic matter turnover and N mineralization rates ([48], [39], [4]). Thinning and its variants (i.e., type, intensity, timing and interactions with other forest practices) can affect soil respiration ([9]). Ryu et al. ([43]) reported increased soil respiration and microbial respiration based on how much soil temperature and moisture rose; however, fine root biomass decreased after thinning treatments. Similarly, Tian et al. ([49]) found that soil respiration increased quickly in the first period after thinning but declined afterwards. In contrast, Campbell et al. ([7]) and Vesala et al. ([53]) reported that thinning had no important effect on soil respiration. These contradictory results show that the effects of thinning on the carbon balance of forests are still poorly understood ([8], [12]).

European Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.) is an important deciduous species that covers 19.962 ha in Turkey, accounting for 0.1% of the country’s forests ([38]). The hornbeam forest featured in the current study was originally coppiced, a management practice with a long history in Turkey. However, traditional coppice management has been mostly abandoned, and former coppice forests were converted to high forest following the decision of the Turkish General Directorate of Forestry in 2006. Old root systems, rapid and fast-growing resprouts, and intensive management with former clear-cuts may produce intrinsic variability in these forest ecosystems, affecting the vegetation cover, litterfall, quality and quantity of forest floor, soil organic matter and biological characteristics of forest floor and soil ([33]).

The main objectives of the present study were: (1) to investigate the effects of thinning on soil respiration and microbial respiration in the forest floor and soil; (2) to determine temporal changes in the main factors influencing soil and microbial respiration (soil temperature, soil moisture, fine root biomass, ground cover, forest floor, soil acidity, soil carbon, soil nitrogen, forest floor carbon, forest floor nitrogen); and (3) to evaluate the correlations of the investigated factors with soil and microbial respiration over a 2-year time frame.

Material and methods

Study site

The study was conducted in the Education and Research Forest of the Faculty of Forestry at Istanbul University, located in Istanbul province, Turkey (41° 09′ 15″ - 41° 11′ 01″ N; 28° 59′ 17″ - 29° 32′ 25″ E). The forest is at an altitude of 90 m a.s.l., the slope is 3% to 5%, and the aspect is west-northwest. Long-term data indicate a maritime climate with medium water deficit in summer; the average annual precipitation is 1111.4 mm, and the mean annual temperature is 12.7 °C. The Luvisol ([19]) soils are well-drained, moderately deep and generally have a loamy clay texture ([1]).

Four sample plots were chosen, which included two areas that were thinned and two control areas (50 × 50 m) in a coppice-originated pure European hornbeam stand. We determined the stand characteristics, including density, mean tree diameter and tree height of the sample plots (Tab. 1). Thinning was established by cutting 50% of the stand basal area. Sampling was confined to the central 25 × 25 m area of each plot to reduce edge effects ([1]).

Tab. 1 - Main stand characteristics of the sample plots.

| Parameter | Control | Thinning |

|---|---|---|

| Density (trees ha-1) | 1408 | 702 |

| Basal area (m-2 ha-1) | 26.2 | 13.0 |

| Mean tree height (m) | 14.3 | 14.2 |

| Mean tree diameter (DBH, cm) | 14.9 | 14.7 |

Sampling and analysis of soil, forest floor, ground cover and fine root biomass

Forest floor (FF) and ground cover (GC) were sampled from 0.25-m2 quadrats in each plot. Forest floor was taken by collecting all the forest floor within the quadrat. After FF and GC samples were collected, steel soil cores (100 cm3) were used to collect soil samples from 0 to 10 cm of the mineral soil at the same points. Five FF, GC and soil samples were taken and bulked for each plot. All bulked or composite samples (forest floor and ground cover) were dried at 65 °C to constant weight and weighed. Soil samples were oven-dried at 105 °C for 48 h and weighed, and the dry bulk density of the samples was calculated. Soil samples were then sieved with a 2-mm screen. Soil acidity (pH, 1/2.5 w/v) was determined with a glass electrode digital pH meter (HI 221®, Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA). All samples were analyzed for their C and N concentrations by dry combustion ([1]) using a LECO CN-2000 analyzer® (LECO Co., St. Joseph, MI, USA).

The biomass of fine roots (FRB) was assessed by collecting five samples quarterly per plots from a depth of 35 cm by using steel soil cores (inner diameter 6.4 cm). Roots were separated from the soil by gently washing them over a series of sieves with mesh sizes of 2.0 mm. The fine roots were oven-dried at 65 °C for 24 h and then weighed ([51]).

Measurement of soil respiration and microbial respiration

Soil respiration (RS) was measured with the soda-lime method. In each plot, five sampling subplots and three sampling occasions (a total of 15 every two months) were chosen for a systematic sampling procedure. A plastic bucket with the same diameter as the soil respiration chambers was established at 1-cm soil depth 24 h prior to any sampling. No live plant parts were inside the plastic bucket to avoid vegetation respiration. CO2 released from the soil inside the plastic bucket was absorbed by 60 g of granular (6-12 mesh) soda lime contained in jars that were 5 cm in diameter and 5 cm in height. Five blank jars were run to account for CO2 absorbance by soda lime during transportation, handling, and the opening and closing of the jars. Before and after each sampling period, the soda lime was oven-dried to constant weight at 105 °C. The mass gain of the soda lime during sampling was determined, and the area of the ground covered by the plastic bucket and the duration of the sampling period were then used to calculate the grams of C released per square meter per day. Measurements were taken bimonthly from October 2010 through October 2012 ([1]).

Soil temperature (TS) at a depth of 0-5 cm was measured immediately adjacent to each soil respiration chamber. In addition, a cylindrical plug of soil 5 cm deep and 5 cm in diameter was collected and placed in an airtight metal tin. Stones, roots and litter were removed by hand, and the samples were weighed, oven-dried at 105 °C, and finally reweighed to determine their gravimetric soil moisture content (WS - [1]).

Microbial respiration was determined by placing 30 g of soil (samples were adjusted to 50-55% water holding capacity) and 10 g of forest floor into 500-ml beakers, which were placed within sealed incubation vessels along with 10 ml of 1 M NaOH and incubated in the dark at 25 °C. The CO2-C evolved was measured every 7 days by adding BaCl2 and subsequently titrated with 1 M HCl ([3]). Soil cores taken from each plot for microbial respiration measurements were used to calculate bulk density (<2-mm oven-dry mass per unit volume, which was defined as g C m-2 d-1 - [1]) .

Statistical analysis

Data were evaluated over four different periods: (1) 1-month results in October 2010 to show that none of the variables were significantly different before the treatment plots were thinned; (2) first year after thinning (2010-2011); (3) second year after thinning (2011-2012); and (4) the whole 2-year (2010-2012) research period. The results were subjected to t-test at the significance level of α=0.05 to identify statistically significant differences between the control and thinned plots within the research period ([1]).

Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to determine the relationships between the dependent variables, which were soil respiration, soil microbial respiration and forest floor microbial respiration, and independent variables, which included soil carbon and nitrogen concentration, soil pH, forest floor carbon and nitrogen concentration. The MiniTab® 16.0 statistical software (MiniTab Inc., State College, PA, USA) was used for all statistical evaluations ([1]).

Results

Effects of thinning on RS

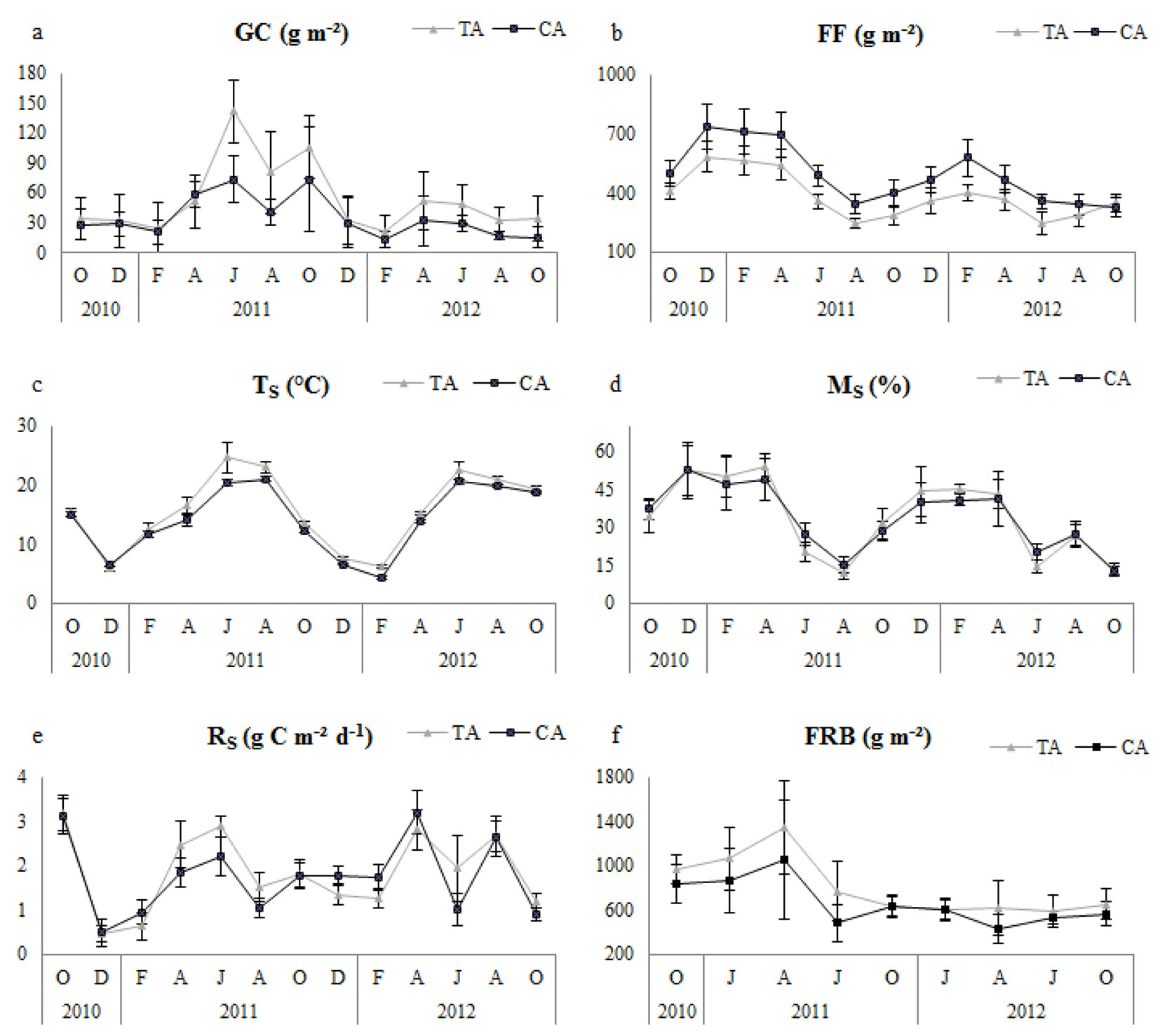

Mean RS was determined to be between 0.45 and 3.18 g C m-2 d-1 in the thinned plots and ranged from 0.49 to 3.20 g C m-2 d-1 in the control plots. RS increased in all plots during the study period, especially in the autumn (Fig. 1). RS was significantly higher (11%) in the thinned plots than in the control plots during the first year only. It did not differ significantly between the two types of plots in the second year or for the 2-year study period (2010-2012 - Tab. 2).

Fig. 1 - Seasonal variation of variables between thinning and control. Error bars represent the standard deviation. (TS): soil temperature; (MS): Soil moisture; (RS): Soil respiration; (FRB): fine root biomass; (GC): ground cover; (FF): forest floor; (TA): thinning area; (CA): control area.

Tab. 2 - Means (± standard deviation, STD) of the investigated parameters and results of the comparison between thinned and control plots (t-test, α = 0.05). (RS): soil respiration; (RSM): soil microbial respiration; (RFFM): forest floor microbial respiration; (FF): forest floor; (GC): ground cover; (TS): soil tempature; (MS): soil moisture; (FRB): fine root biomass; (FF N): forest floor nitrogen; (FFC): forest floor carbon; (FF C/N): forest floor C/N ratio; (TA): thinning area; (CA): control area.

| Variable | Plot | Pre-treatment (October 2010) |

2010-2011 | 2011-2012 | 2010-2012 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± STD | p-value | Mean ± STD | p-value | Mean ± STD | p-value | Mean ± STD | p-value | ||

| RS (g C m-2 d-1) |

TA | 2.88 ± 0.40 | 0.877 | 1.76 ± 0.10 | 0.002 | 1.77 ± 0.14 | 0.215 | 1.76 ± 0.08 | 0.247 |

| CA | 2.91 ± 0.39 | 1.59 ± 0.11 | 1.85 ± 0.14 | 1.72 ± 0.08 | |||||

| RSM (g C m-2 d-1) |

TA | 0.91 ± 0.33 | 0.187 | 0.76 ± 0.08 | 0.150 | 0.95 ± 0.08 | 0.881 | 0.87 ± 0.06 | 0.221 |

| CA | 1.12 ± 0.37 | 0.83 ± 0.13 | 0.84 ± 0.17 | 0.86 ± 0.12 | |||||

| RFFM (g C m-2 d-1) |

TA | 0.95 ± 0.83 | 0.918 | 0.53 ± 0.08 | 0.002 | 0.59 ± 0.10 | 0.012 | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 0.001 |

| CA | 0.98 ± 0.60 | 0.90 ± 0.31 | 0.84 ± 0.19 | 0.87 ± 0.24 | |||||

| FF (g m-2) |

TA | 409.00 ± 176 | 0.367 | 420.09 ± 72.33 | 0.020 | 333.41 ± 46.90 | 0.000 | 376.75 ± 52.37 | 0.000 |

| CA | 499.00 ± 254 | 543.62 ± 125.96 | 441.51 ± 65.72 | 492.56 ± 88.09 | |||||

| GC (g m-2) |

TA | 34.30 ± 20.9 | 0.452 | 66.92 ± 14.56 | 0.001 | 36.83 ± 7.69 | 0.002 | 51.88 ± 9.63 | 0.000 |

| CA | 28.00 ± 15.7 | 43.17 ± 10.85 | 22.67 ± 9.26 | 32.92 ± 6.92 | |||||

| TS (°C) |

TA | 15.37 ± 0.76 | 0.212 | 15.73 ± 0.56 | 0.000 | 14.45 ± 0.39 | 0.002 | 15.09 ± 0.43 | 0.000 |

| CA | 15.02 ± 0.35 | 14.40 ± 0.20 | 13.97 ± 0.18 | 14.19 ± 0.15 | |||||

| MS (%) |

TA | 34.33 ± 6.32 | 0.267 | 36.30 ± 2.06 | 0.758 | 31.52 ± 3.19 | 0.760 | 33.91 ± 1.76 | 0.679 |

| CA | 37.11 ± 4.30 | 36.62 ± 2.46 | 32.01 ± 3.82 | 34.31 ± 2.44 | |||||

| pH (H2O) |

TA | 4.91 ± 0.26 | 0.132 | 4.80 ± 0.14 | 0.000 | 4.93 ± 0.09 | 0.000 | 4.86 ± 0.11 | 0.000 |

| CA | 5.13 ± 0.34 | 5.13 ± 0.12 | 5.35 ± 0.18 | 5.24 ± 0.06 | |||||

| FRB (g m-2) |

TA | 969.00 ± 129 | 0.07 | 1071.07 ± 188.32 | 0.001 | 609.09 ± 56.95 | 0.013 | 840.08 ± 79.89 | 0.000 |

| CA | 834.00 ± 172 | 799.45 ± 105.28 | 546.12 ± 44.12 | 672.79 ± 60.89 | |||||

| Soil N (%) |

TA | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.969 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.059 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 0.571 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.768 |

| CA | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | |||||

| Soil C (%) |

TA | 5.36 ± 0.17 | 0.161 | 5.81 ± 0.13 | 0.782 | 4.88 ± 0.60 | 0.166 | 5.34 ± 0.27 | 0.148 |

| CA | 5.49 ± 0.20 | 5.82 ± 0.13 | 4.60 ± 0.08 | 5.21 ± 0.05 | |||||

| Soil C/N | TA | 22.50 ± 4.18 | 0.932 | 24.16 ± 0.74 | 0.235 | 19.35 ± 2.63 | 0.119 | 21.75 ± 1.44 | 0.522 |

| CA | 22.64 ± 3.07 | 24.93 ± 1.84 | 17.82 ± 1.32 | 21.38 ± 1.13 | |||||

| FF N (%) |

TA | 1.26 ± 0.06 | 0.931 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.000 | 1.01 ± 0.05 | 0.005 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.001 |

| CA | 1.25 ± 0.06 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 1.07 ± 0.04 | 1.06 ± 0.04 | |||||

| FF C (%) |

TA | 37.85 ± 1.48 | 0.418 | 41.11 ± 0.74 | 0.527 | 42.48 ± 0.77 | 0.086 | 41.79 ± 0.32 | 0.095 |

| CA | 37.00 ± 2.84 | 41.29 ± 0.46 | 43.46 ± 1.54 | 42.37 ± 1.00 | |||||

| FF C/N | TA | 30.22 ± 2.23 | 0.514 | 63.86 ± 11.07 | 0.000 | 46.68 ± 0.77 | 0.002 | 55.24 ± 6.59 | 0.001 |

| CA | 29.55 ± 2.23 | 41.23 ± 2.41 | 43.46 ± 1.54 | 46.88 ± 1.00 | |||||

Temporal variation of TS was higher in the thinned plots, generally in the summer period from the beginning of April; moreover, it showed a parallel tendency on both thinned and control plots (Fig. 1). Similarly, GC showed similar temporal trends for thinned and control plots, and it was always higher in thinned plots (Fig. 1). Temporal variation of FF was always higher in control plots. MS did not show significant differences (Tab. 2), and it had similar temporal variation (Fig. 1) for both control and thinned plots. FRB showed seasonal fluctuations and was higher in thinned plots (Fig. 1). In summary, TS, FF, GC and FRB were significantly different between control and thinned plots over the first year, second year and 2-year study period (Tab. 2).

Effects of thinning on RSM and RFFM

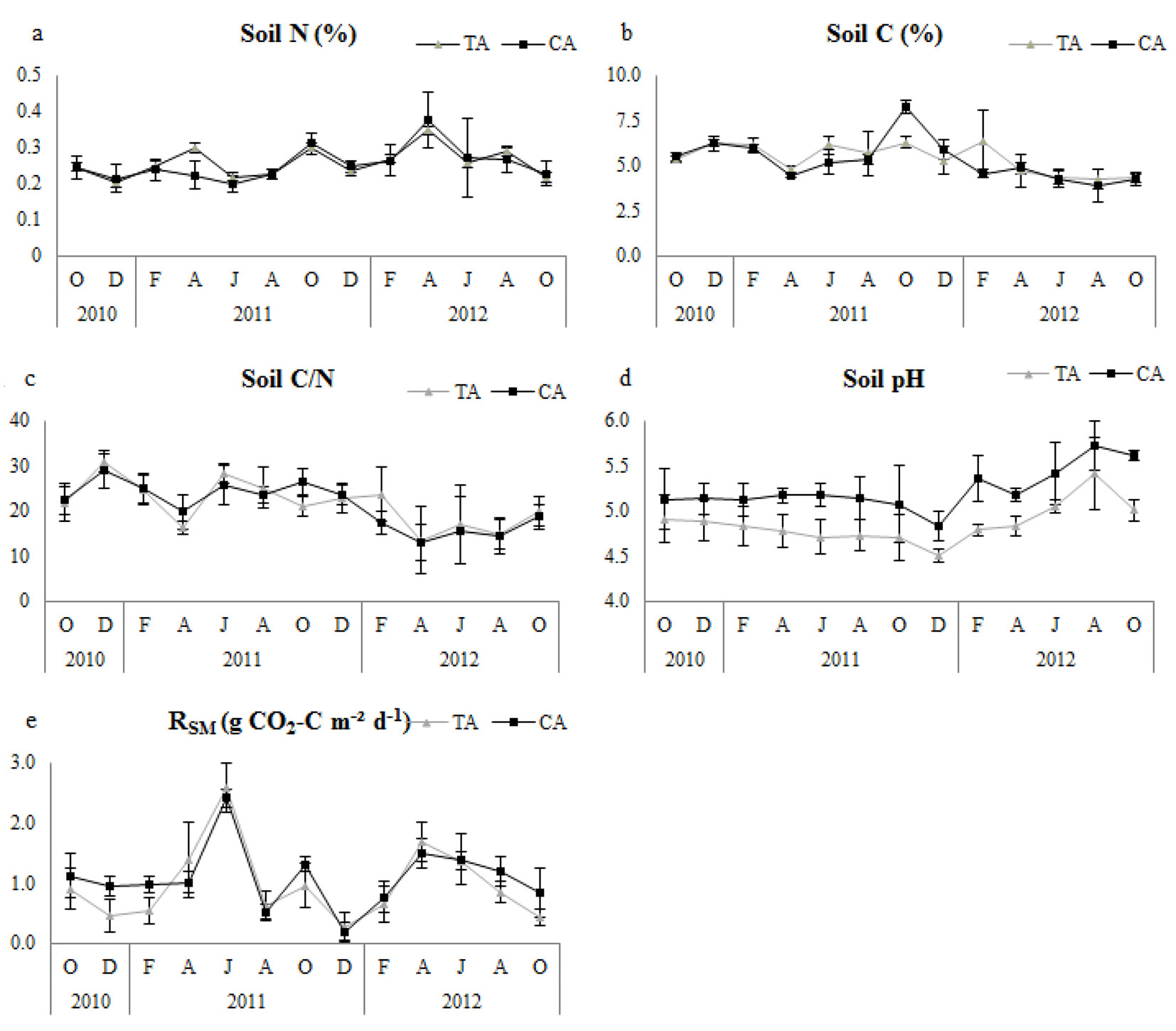

Temporal variation of soil microbial respiration (RSM) fluctuated similarly on both thinned (0.25-2.22 g C m-2 d-1) and control plots (0.16-2.12 g C m-2 d-1), and it mirrored the temporal variation of RS (Fig. 2). RSM did not show statistically significant differences between control and thinned plots in any of the research periods (Tab. 2).

Fig. 2 - Temporal changes of soil microbial respiration (RSM) and related variables in thinning and control plots. Error bars represent the standard deviation. (Soil N): soil nitrogen; (Soil C): soil carbon; (TA): thinning area; (CA): control area.

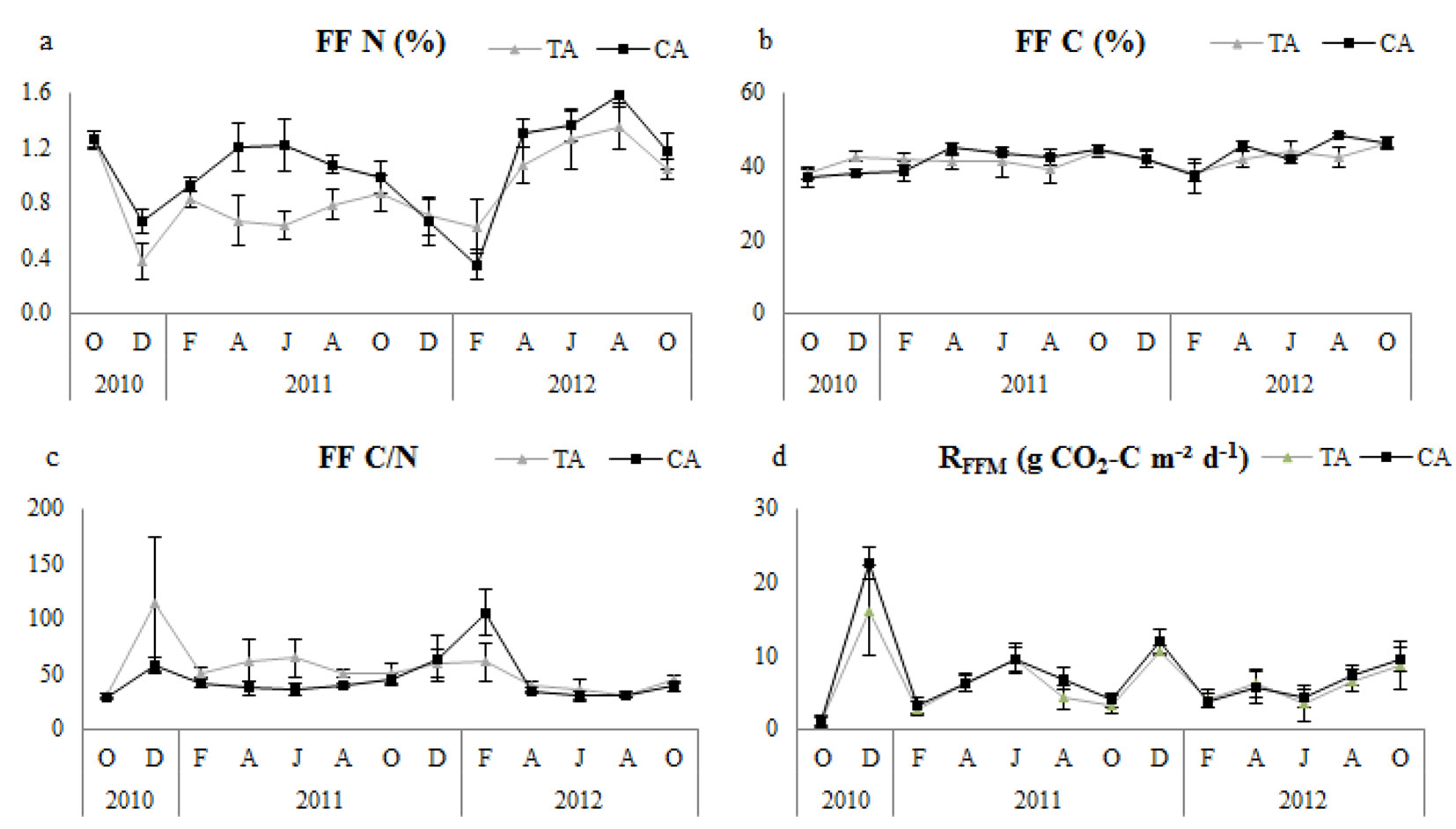

Microbial respiration of forest floor (RFFM) was between 0.09 and 2.11 g C m-2 d-1 in thinned plots and ranged from 0.12 to 4.05 g C m-2 d-1 in control plots. Temporal variation of RFFM was similar to RSM (Fig. 3), and RFFM was 73%, 42% and 54% greater for control plots compared to thinned plots for the first year, second year and the 2-year study period, respectively (Tab. 2).

Fig. 3 - Temporal changes of forest floor microbial respiration (RFFM) and related variables in thinning and control plots. Error bars represent the standard deviation. (FF N): forest floor nitrogen; (FF C): forest floor carbon; (TA): thinning area; (CA): control area.

Soil N, soil C and soil C/N ratio were not significantly different between control and thinned plots in any of the research periods (Tab. 2). All plots had similar tendencies with regard to soil pH (Fig. 2), but it was significantly higher in control plots (Tab. 2). Control plots had significantly higher nitrogen concentration of forest floor (FFN) in all study periods, but forest floor carbon (FFC) did not differ significantly (Tab. 2); however, the forest floor C/N ratio (FFC/N) was significantly higher in thinned plots (Tab. 2). Temporal variation of FFN and FFC/N showed similar tendencies, especially during the second year in all plots (Fig. 3).

Relationships between RS and variables

In thinned plots, in general, Rs was positively correlated with GC, TS and FRB during both the annual and 2-year study periods; however, significantly negative relationships were determined with FF for the 2-year research period and with Ms in the first year and the 2-year research period (Tab. 3). In control plots, Rs had a significantly linear correlation with GC in the first year and the 2-year research period, a significant correlation with TS for the first year only, and a negatively significant correlation with FF for the 2-year period. No significant correlation existed between RS and FRB in any of the research periods, and a significant correlation with MS was detected only for the second year (Tab. 3).

Tab. 3 - Correlation results of the soil respiration with related factors. (TA): thinning area; (CA): control area; (TS): soil temperature; (MS): soil moisture; (RS): soil respiration; (FRB): fine root biomass; (GC): ground cover mass; (FF): forest floor mass; (*): p < 0.05; (**): p < 0.01.

| Variable | Period | Plot | FF (g m-²) |

GC (g m-²) |

MS (%) |

TS (°C) |

FRB (g m-²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS (g C m-2 d-1) |

2010-2011 | TA | -0.219 | 0.461** | -0.354** | 0.582** | 0.367** |

| CA | -0.200 | 0.356** | -0.160 | 0.386** | 0.183 | ||

| 2011-2012 | TA | -0.200 | 0.531** | 0.030 | 0.437** | 0.295* | |

| CA | 0.004 | 0.178 | 0.497** | -0.144 | -0.109 | ||

| 2010-2012 | TA | -0.206* | 0.434** | -0.203* | 0.505** | 0.272** | |

| CA | -0.153* | 0.228* | 0.146 | 0.090 | 0.034 |

Relationships between RSM, RFFM and variables

In thinned plots, RSM showed significant positive correlations with soil pH (except in the first year) and soil N. However, it had a significant and strong negative relationship with soil C and soil C/N ratio for all research periods (Tab. 4). In control plots, RSM had a significant linear relationship with soil N and soil pH (except in the second year), and a significant negative correlation with soil C and soil C/N ratio (except in the first year for both - Tab. 4).

Tab. 4 - Correlation results of the microbial soil respiration with related factors. (TA): thinning area; (CA): control area ; (RSM): soil microbial respiration; (C): soil carbon; (N): soil nitrogen; (*): p < 0.05; (**): p < 0.01.

| Variable | Period | Plot | pH | C (%) | C/N | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSM (g C m-² d-1) |

2010-2011 | TA | 0.099 | -0.729** | -0.784** | 0.683** |

| CA | 0.379** | 0.213 | -0.076 | 0.261* | ||

| 2011-2012 | TA | 0.314** | -0.392** | -0.508** | 0.621** | |

| CA | 0.161 | -0.418** | -0.554** | 0.418** | ||

| 2010-2012 | TA | 0.319** | -0.551** | -0.596** | 0.616** | |

| CA | 0.284** | -0.291** | -0.499** | 0.429** |

RFFM showed a significant positive correlation with forest floor C/N ratios and FFC (except in the first year) and a negative correlation with FFN in thinned plots for all research periods (Tab. 5). In control plots, RFFM showed a significant linear relationship with FFC (except in the second year) and C/N ratios of forest floor, and a significant negative correlation with FFN for all research periods (Tab. 5). Correlation results showed that changes in factors in the first year had a higher effect on the temporal variation of RFFM in the thinned and control plots.

Tab. 5 - Correlation results of the microbial forest floor respiration with related factors. (TA): thinning area; (CA): control area; (RFFM): forest floor microbial respiration; (FFC): forest floor carbon; (FFN): forest floor nitrogen; (*): p < 0.05; (**): p < 0.01.

| Variable | Period | Plot | FFC % | FFN % | C/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFFM (g C m-² d-1) |

2010-2011 | TA | 0.148 | -0.716** | 0.763** |

| CA | 0.388** | -0.739** | 0.759** | ||

| 2011-2012 | TA | 0.415** | -0.302* | 0.279* | |

| CA | 0.213 | -0.271* | 0.479** | ||

| 2010-2012 | TA | 0.292** | -0.502** | 0.561** | |

| CA | 0.236** | -0.298** | 0.416** |

Discussion

Effects of thinning on RS

Thinning can affect the RS rate, which is an important determinant of soil carbon cycle and ecological factors such as root mass, root chemistry, soil moisture and soil temperature ([6], [43]). The mean annual RS in this study was significantly higher in the thinned plots compared to the control plots only in the first year. The RS rates did not differ significantly in either the second year or throughout the 2-year study period. These results were consistent with those of several previous research studies. For example, Vesala et al. ([53]) and Campbell et al. ([7]) reported that thinning did not greatly affect soil respiration. In addition, Tian et al. ([49]) found that soil respiration increased quickly in the first period after thinning and declined afterward.

In our study, of all factors evaluated, GC and TS had the greatest positive influence on RS following FRB. Similarly, Liang et al. ([27]) reported that the understory plant biomass strongly controlled the soil CO2 efflux owing to the root production in the thinned forest stands, which was consistent with previous studies ([44], [54], [17], [23], [37]). Ground cover species were not identified in the current study, however, the species makeup can influence soil respiration. For example, Dias et al. ([11]) found a linear relationship between soil respiration and plant species diversity of ground cover. Further, Mäkiranta et al. ([34]) detected a positive correlation between ground cover biomass and respiration. Nevertheless, the role of ground cover is rarely considered in the analysis of carbon balance in forest ecosystems ([16], [25], [22]), and it is essential to understand the effects of thinning on Rs when evaluating the reaction of undergrowth vegetation ([27]).

Soil temperature and moisture significantly affect soil respiration. We found that thinning positively affected soil temperature in all research periods, while the relationship of soil moisture with RS was significantly negative in the first year and over the two-year research period in the thinned plots. Our findings are consistent with those of Graf et al. ([18]) and Joo et al. ([20]), who found that soil respiration was strongly correlated with soil temperature. However, Sullivan et al. ([47]) reported that soil temperature did not differ significantly between the thinned plots and the control sites, suggesting that thinning did not alter soil CO2 efflux because of soil temperature variation, though it might change the soil physical environment. Nevertheless, several researchers have stated that soil temperature is a key component in estimating the CO2 flux from forest soils ([21], [29], [41], [10], [26], [48], [18], [39]). It has also been noted that thinning increases canopy opening, which in turn increases the amount of sunlight reaching the forest floor ([43]).

Thinning can change tree biomass and root density. In the present study, fine root biomass was significantly higher in the thinned plots. Our results disagree with previous studies that demonstrated a reduction in fine root biomass after thinning ([45], [28], [52], [43], [39], [40]). The main reason that fine root biomass was higher in the thinned plots is probably related to the increased ground cover biomass after the thinning treatment.

Decomposition occurring in the forest floor can support soil respiration for a short period of time ([46], [36], [47], [39]). Our results for all study periods demonstrate that the forest floor mass was significantly higher in the control plots, most likely because of the decreased tree density and reduced litter fall contribution to forest floor in the thinned plots or because of increased decomposition. Similar to our results, Makineci ([32]) found less forest floor litter after thinning. Furthermore, the negative relationship between FF and RS in the 2-year period in both the thinned and control plots suggest that soil respiration increased owing to the decreased FF mass. However, Luo & Zhou ([30]) reported that decreased FF mass caused by decomposition and thinning might increase soil respiration because of the reduced resistance of CO2 diffusion on the soil surface.

Thinning effects on RSM and RFFM

We did not find significant differences in RSM between the thinned and control plots. This result suggests that soil microbial activity and respiration did not change after thinning. This interpretation is supported by soil carbon and nitrogen concentrations not being significantly different between the thinned and control plots. Similarly, Son et al. ([46]) found no significant differences in microbial activity during decomposition among plots with different thinning intensities. In contrast, Giai & Boerner ([14]) found higher microbial activity in thinned plots compared to control plots. Despite the non-significant changes between the thinning treatment and the control, RSM of thinned plots usually had strong positive correlations with soil pH and soil nitrogen concentration, and strong negative correlations with soil carbon concentration and soil C/N ratio. Several authors have stated that soil microbial respiration is linearly correlated with both soil carbon and nitrogen concentrations ([35], [50], [5]). In this context, Luo & Zhou ([30]) reported that a positive correlation exists between the mineralized nitrogen ratio and microbial respiration because of the binding of mineralized nitrogen with carbon during the microbial decomposition of soil organic matter. However, Rodeghiero & Cescatti ([42]) found that microbial respiration decreased as the soil nitrogen concentration increased.

RFFM of thinned plots was significantly lower than that of the control for all research periods. This finding may be associated with the decreased microbial activity and respiration of forest floor in the thinned areas due to the environmental changes. Consistent with our study, Lindo & Visser ([28]) found that forest floor microbial respiration decreased considerably after thinning treatments. Microbial respiration in forest floor had a statistically significant and strong positive correlation with carbon concentration and C/N ratio of forest floor and a significantly negative correlation with nitrogen concentration. Microorganisms consume carbohydrate and protein-based compounds as nutrients ([24], [31]), and our results might also be interpreted as indicating increased microbial consumption of protein-based (nitrogen) and sugar-based (carbohydrate) compounds in soil and forest floor.

Conclusion

Determining soil respiration is important because it has in general a positive relationship with net ecosystem productivity. Higher RS rates in thinned plots are therefore important for net ecosystem productivity. In this study, ground cover mass and soil temperature were found to have the largest effects on RS among the investigated factors. In this context, a specific evaluation of ground cover (species composition or cover degree) may clarify such effects in future studies. RSM did not differ significantly among plots, although it was higher in the thinned plots over the study period. In contrast, microbial respiration in forest floor was higher in the control plots than in the thinned plots. In a similar study ([2]) with the same thinning intensity in a neighboring stand of Hungarian oak (Quercus frainetto Ten.), we obtained results that differed from the findings of the present study, which suggests that thinning might yield species-specific outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This paper reports part of the results from the PhD thesis of Serdar Akburak under the supervision of Ender Makineci completed in 2013 at the Science Institute, Istanbul University, Turkey. This work was supported by the Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit of Istanbul University, Project numbers: 9652 and UDP-51525. It was presented as a poster presentation titled “Thinning effects on soil and microbial respiration of forest floor and soil in European hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.) forest in Istanbul - Turkey”, and its abstract was published in the abstracts book of the Conference “Coppice 2015- Coppice Forests: Past, Present and Future” in Brno, Czech Republic, 9-11 April 2015.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Ender Makineci

Istanbul University, Faculty of Forestry, Soil Science and Ecology Department, 34473 Bahcekoy, Sariyer, Istanbul (Turkey)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Akburak S, Makineci E (2016). Thinning effects on soil and microbial respiration in a coppice-originated Carpinus betulus L. stand in Turkey. iForest 9: 783-790. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1810-009

Academic Editor

Tomas Vrska

Paper history

Received: Aug 12, 2015

Accepted: Apr 04, 2016

First online: May 29, 2016

Publication Date: Oct 13, 2016

Publication Time: 1.83 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2016

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 52034

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 42362

Abstract Page Views: 3802

PDF Downloads: 4409

Citation/Reference Downloads: 44

XML Downloads: 1417

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 3535

Overall contacts: 52034

Avg. contacts per week: 103.04

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2016): 20

Average cites per year: 2.00

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Fine root morphological traits and production in coniferous- and deciduous-tree forests with drained and naturally wet nutrient-rich organic soils in hemiboreal Latvia

vol. 16, pp. 165-173 (online: 08 June 2023)

Research Articles

Fine root production and distribution in the tropical rainforests of south-western Cameroon: effects of soil type and selective logging

vol. 3, pp. 130-136 (online: 27 September 2010)

Research Articles

Short-term recovery of fine root carbon stock is inhibited by skid trails in a humid tropical forest

vol. 18, pp. 344-349 (online: 30 November 2025)

Research Articles

Controlling soil total nitrogen factors across shrublands in the Three Rivers Source Region of the Tibetan Plateau

vol. 13, pp. 559-565 (online: 29 November 2020)

Research Articles

The manipulation of aboveground litter input affects soil CO2 efflux in a subtropical liquidambar forest in China

vol. 12, pp. 181-186 (online: 10 April 2019)

Research Articles

Impacts of Norway spruce (Picea abies L., H. Karst.) stands on soil in continental Croatia

vol. 12, pp. 511-517 (online: 02 December 2019)

Research Articles

Soil respiration and carbon balance in a Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys heterocycla (Carr.) Mitford cv. Pubescens) forest in subtropical China

vol. 8, pp. 606-614 (online: 02 February 2015)

Research Articles

Soil respiration along an altitudinal gradient in a subalpine secondary forest in China

vol. 8, pp. 526-532 (online: 01 December 2014)

Research Articles

Effects of understory removal on root production, turnover and total belowground carbon allocation in Moso bamboo forests

vol. 9, pp. 187-194 (online: 20 November 2015)

Research Articles

Short-time effect of harvesting methods on soil respiration dynamics in a beech forest in southern Mediterranean Italy

vol. 10, pp. 645-651 (online: 20 June 2017)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword