Identification and molecular characterization of LTR and LINE retrotransposable elements in Fagus sylvatica L.

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 2, Issue 3, Pages 119-126 (2009)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor0501-002

Published: Jun 10, 2009 - Copyright © 2009 SISEF

Research Articles

Collection/Special Issue: COST Action E52 Meeting 2008 - Florence (Italy)

Evaluation of beech genetic resources for sustainable forestry

Guest Editors: Georg von Wühlisch, Raffaello Giannini

Abstract

Retrotransposable elements are important and peculiar genetic components derived from ancient retrovirus insertion inside plants genome. Their ability to move and/or replicate inside the genome is an important evolutionary force, responsible for the increase of genome size and the regulation of gene expression. Retrotransposable elements are well characterized in model or crop species like Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa, but are poorly known in forest tree species. In this paper the molecular identification of retrotransposable elements in Fagus sylvatica L. is reported. Two retrotransposons, belonging to the two major classes of LTR and non-LTR elements, were characterized trough a SCAR (Sequence Characterized Amplified Region) strategy. The analysis demonstrated the presence of multiple copies of retrotransposable elements inside the genome of beech, in accordance with the viral quasi-species theory of retrotransposon evolution. The cloning and sequencing of amplification products and a Cleaved Amplified Polymorphisms (CAPs) approach on the identified retrotransposons, showed a high level of diversity among the multiple copies of both elements. The identification of retrotransposable elements in forest trees represents an important step toward the understanding of mechanisms of genome evolution. Furthermore, the high polymorphism of retrotransposable elements can represent a starting point for the development of new genetic variability markers.

Keywords

Fagus sylvatica, Retrotransposons, Genome evolution, Genetic diversity

Introduction

Transposable elements (TEs) are ancient (retro)-virus insertions inside a host genome and are peculiar mobile genetic elements accounting for a large proportion of repetitive DNA regions ([29]). TEs (Fig. 1) are classified according to their origin and structure ([6], [44]). Class II DNA mediated TEs are usually in low copy number as they transpose with a “cut and paste” process ([4]) and are particularly important in prokaryotic and animal genetics ([6], [18], [3]). Miniature Inverted TEs (MITEs) are defective, non autonomous forms of DNA transposons and are the predominant TE type in or near plant genes ([10]). Retrotransposons (RNA mediated Class I TEs) are the most widespread class of eukaryotic TE, particularly relevant in shaping plant genomes ([10], [44]).

Fig. 1 - Schematic representation of the general structure of class I RNA mediated LTR TE (A), class I RNA mediated non-LTR elements (B) and class II DNA mediated elements (C) in their autonomous and non autonomous configurations. TIR, Terminal Inverted Repeats; LTR, Long Terminal Repeats; pol gene contains: PR, protease; EN, endonuclease; RT reverse transcriptase; INT, integrase; gag gene encodes a capsid like protein.

Retrotransposons can be classified in two main classes ([10]): non-LTR and LTR elements characterized, respectively, by the absence or presence of long repeated regions flanking the ORFs core. LTR retrotransposons, if still active, increase their copy number with their copy-and-paste mode of transposition. Non-LTR retrotransposons can be divided in several subclasses, such as LINE (Long INterspersed Elements) and SINE (Short INterspersed Elements - [44]). Both LINEs and SINEs elements, despite the differences in structure and transposition mechanisms ([44]), are ubiquitous components of eukaryotic genomes, playing a major role in their evolution.

LTR and non-LTR retrotransposons are common in plant genomes where they can be present in high copy number, ranging from 20000 to 200000 copies of copia-like LTR elements in barley and maize ([37], [23]); the gypsy LTR element is present in 20000 copies in maize. There are 250000 copies of LINE elements in Lilium ([21]) and SINEs are represented, for example, by 50000 copies in tobacco ([46]). It is therefore clear that retrotransposable elements build large parts of eukaryotic genomes ([40]). They represent, for example, a 20% genomic fraction in Drosophila melanogaster ([17]), 45% in human ([33]) and over 80% in maize ([29]).

The observed differences in genome size in plants are accompanied by variations in the content of LTR retrotransposons, demonstrating that such elements might be important players in the evolution of plant genomes, along with polyploidy ([11]). The analysis of these elements have also revealed that plant genomes underwent genome amplifications (retrotransposition) and contractions (homologous or illegitimate recombination) leading Vitte & Panaud ([39]) to the definition of the increase/decrease model of genome evolution.

TEs have also an important role in gene evolution and regulation ([45]). Even if they usually integrate into intergenic regions, in maize both LTR-retrotransposons and MITEs elements have been frequently found associated to genes ([42]).

Retrotransposition can directly affects gene expression by integrating into coding or regulatory regions ([43], [8]); it also acts on tissue specific alternative splicing if inserted in intron regions ([22]). Deleterious effects of TEs movement and replication are controlled by the development of mechanisms limiting their mutagenic activity, being silencing, probably, the most general and effective one ([35]).

Since retrotransposable elements are abundant, ubiquitous and highly conserved (especially the LTR elements), they have drawn much attention for the development of genetic diversity and mapping markers; several methods use the high level of homology of LTR regions as annealing sites for PCR based strategies such as S-SAP ([41]), IRAP and REMAP ([14]). These methods have been advantageously used for variability screenings in several species ([15]) such as wheat ([27]), pea ([30]) and tomato ([31]). Recently retrotransposable elements have also been used for cultivar fingerprinting and certification ([36]).

TEs are quite well characterized in crops, model species or agronomical important woody perennials like Malus ([36]), Citrus, Prunus ([2]) and Vitis ([13]), whilst in forest trees they are characterized only in conifers ([16], [19], [12]).

In this paper, the molecular identification of LTR and non-LTR LINE retrotransposable elements in the genome of Fagus sylvatica is reported. The characterization of these peculiar genetics elements demonstrated their multi-copy presence inside beech genome. The analysis of the polymorphism shown by the identified retrotransposable elements leads also to the proposal of the development of new genetic diversity markers.

Materials and methods

Identification of retrotransposable elements in Fagus sylvatica

Retrotransposable elements of Fagus sylvatica were identified trough cloning and sequencing of RAPD (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA) markers obtained during a genetic diversity screening of Italian beech populations ([9]). In such work 1000 beech trees from 30 populations of Southern Italy were analysed with 3 random 10-mer primers (1253, 1247 and RF2 - [26]), obtaining 90 reproducible markers. Only two RAPD markers (named 1253/1 and RF2/35) showed a 100% frequency in the dataset and were therefore characterized by using the SCAR (Sequence Characterized Amplified Region) strategy.

SCAR strategy

The two RAPD fragments selected (1253/1: 2000 bp and RF2/35: 680 bp) were excised from agarose gels and purified with the Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK), following the manufacturer’s specification. DNA fragments were then cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK), following the manufacturer’s specifications. Plasmids from positively transformed clones were extracted using the Qiagen Plasmid Extraction Kit and the inserted fragment was sequenced in both directions using an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California).

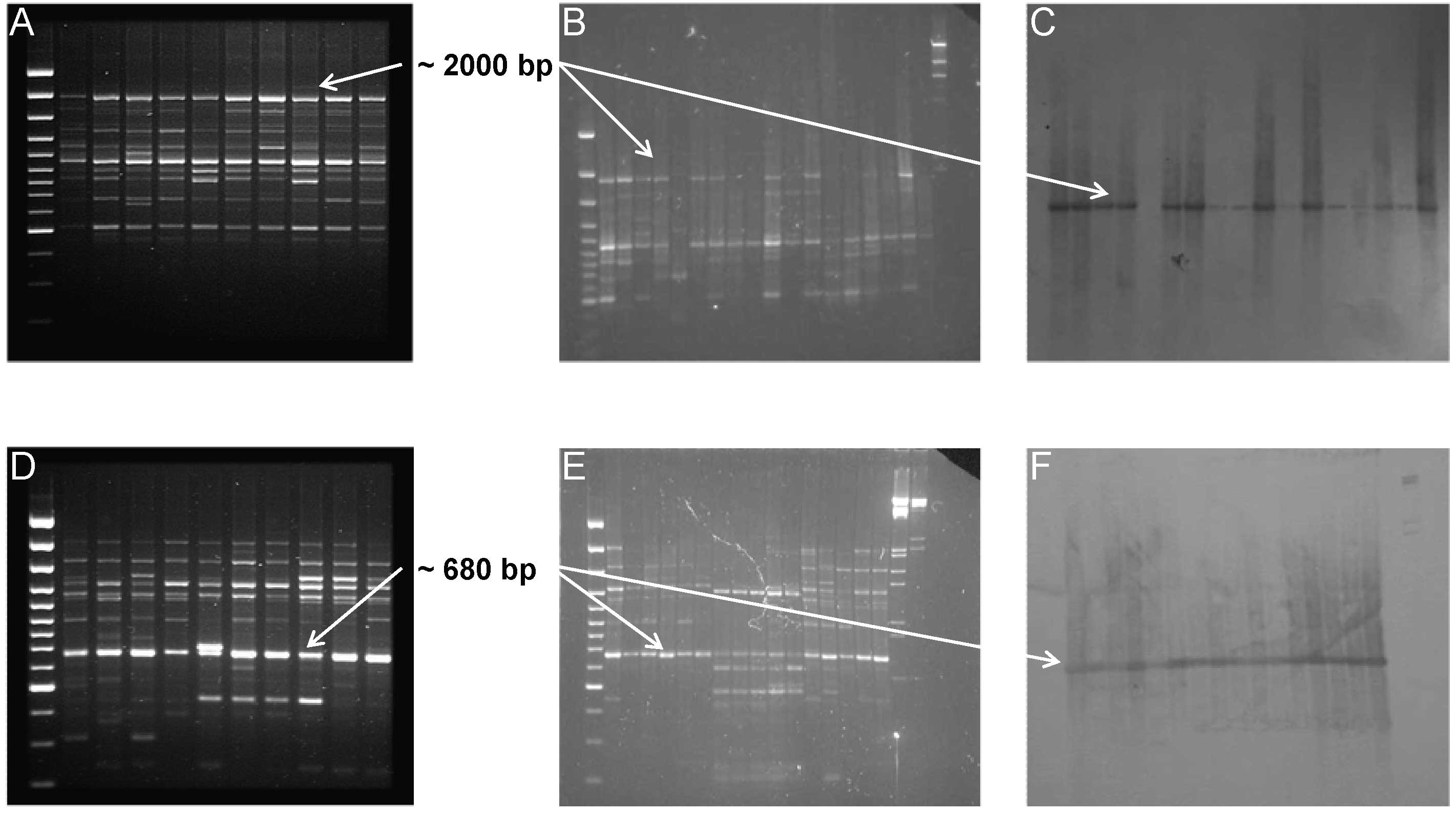

To ensure the homology between the two cloned fragments and the RAPD markers (1253/1, RF2/35), the absence of co-migrant markers and repetitive fragments in the RAPD fingerprinting, high stringency Southern Blot analyses were performed (following the protocol reported in [26]) using the cloned fragments as probes against the RAPD profile (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 - Southern Blot analysis of RAPD fragments; RAPD profiles showing the characterized fragments representing the non-LTR (A) and LTR (D) retrotransposable elements. Blotting gels (B,E) and colorimetric results (C, F) of hybridisation analysis.

Sequence analysis

High quality sequences were used as queries for database searching using the BLAST tool ([1]). Homologous sequences were aligned using the ClustalW software ([20]). The analysis of sequence polymorphism was performed using the MEGA4 software ([32]).

Analysis of retrotransposable elements diversity in different beech genotypes

The identified retrotransposable elements of beech were furthermore analysed trough cloning and sequencing of specific amplified fragments. Primers were designed using the Primer3 on-line tool ([28]) to amplify a region (fragments made up of 357 and 501 base pair, respectively, for the LTR and non-LTR elements) for each retrotransposon identified. Primers for the non-LTR Retrotransposable elements were: 5’ - CGATTTGTCCTACCTGCTTG-3’, 5’- CCGCCCTATTAGTTTGATTGG - 3’; primers for the LTR Element were: 5’ - AACCGACATGGGTAACTTCG - 3’, 5’ - CCA CACAGTACTCGTTCAAATCT - 3’. Both fragments were amplified using a sequencing PCR cycle with an annealing temperature of 60 °C. Reactions were performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Perkin Elmer) with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 µM for each dNTP, 1 μM for each primer and 1 U of TaqDNA polymerase (Invitrogen - final volume 20 µl).

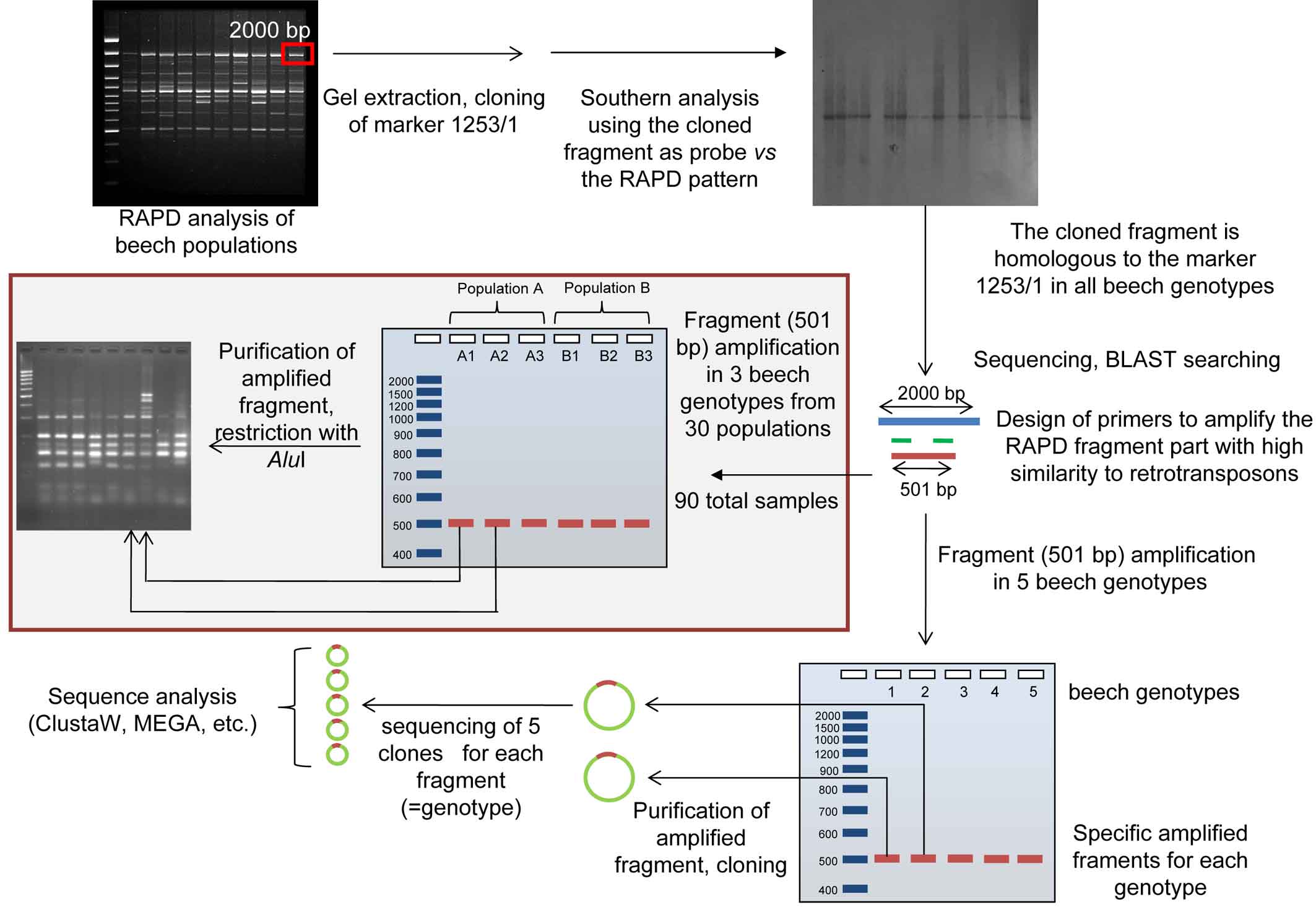

In order to preliminarily evaluate the diversity of retrotransposable elements in different genotypes, specific amplification fragments of a randomly selected tree from 5 beech populations (belonging to the dataset used in [9] and selected for the high genetic diversity obtained with RAPD markers) were produced for both retroelements, using the primers and the amplification conditions reported above. The two specific amplicons of the retrotransposons were purified with the Qiagen PCR Purification Kit, cloned, sequenced and analysed as already reported. 5 clones for each genotype (for a total of 25 clones) and for each retrotransposon were sequenced (50 sequences in total - Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 - Experimental flow chart of beech retrotransposable elements characterization. The grey shaded boxed part is valid only for the non-LTR element.

CAPs analysis of non-LTR element polymorphism

For CAPs analysis, the non-LTR reverse transcriptase fragments (501 base pair) from 3 randomly selected individuals for each of the 30 beech populations analysed by Emiliani et al. ([9]) - 90 total samples - were amplified using the primers reported above. The amplification products were purified using the Qiagen PCR Purification Kit following the manufacturer’s specification and digested for 4 hours with 10 U of AluI restriction endonuclease (Takara, Japan). Digestion patterns were loaded on 4% (w/v) agarose gels and analysed with the Photo-Capt software (Vilber-Lourmat, France).

The whole experimental flowchart is reported as Fig. 3.

Results and discussion

Molecular identification of retrotransposable elements in Fagus sylvatica

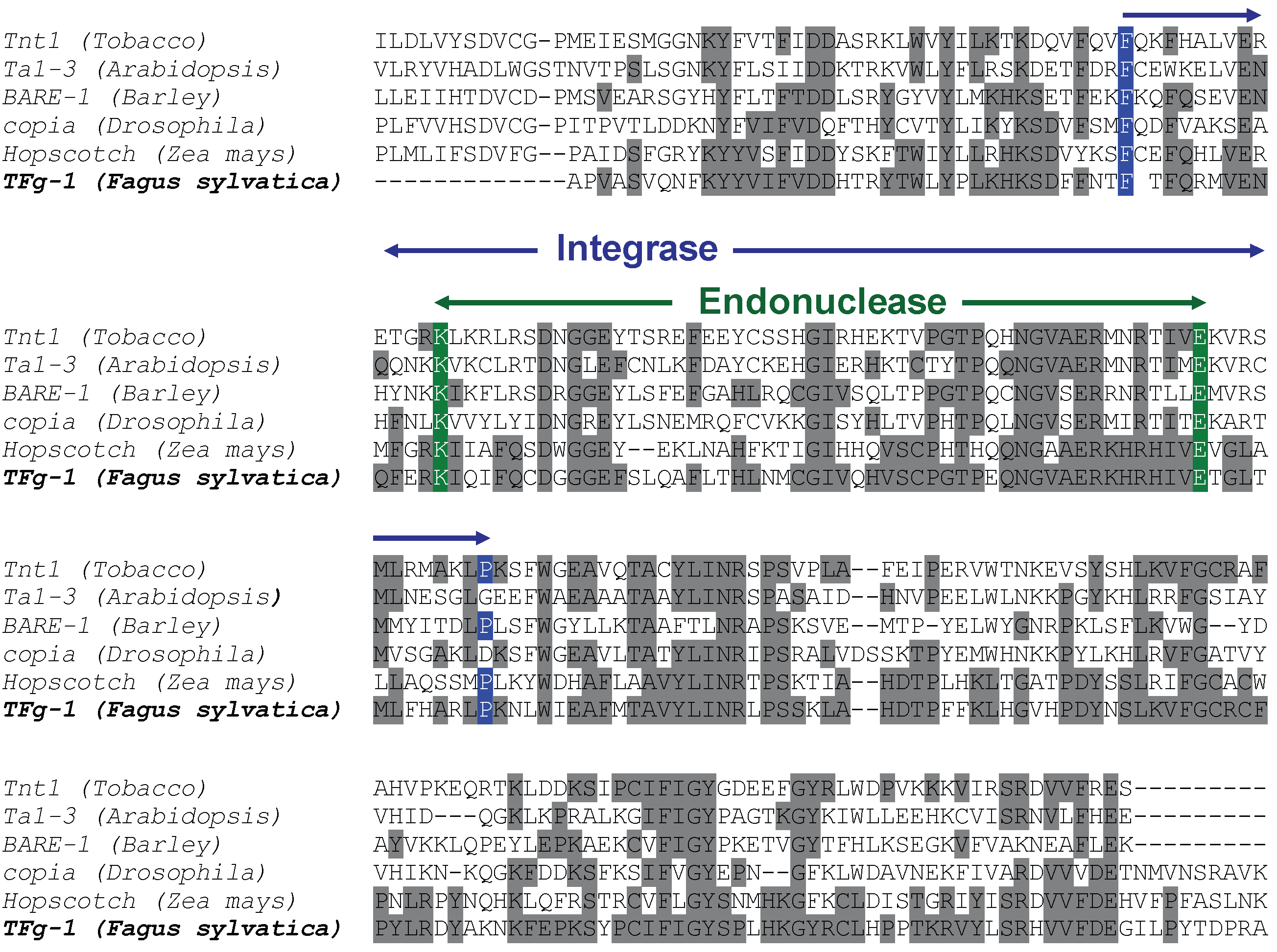

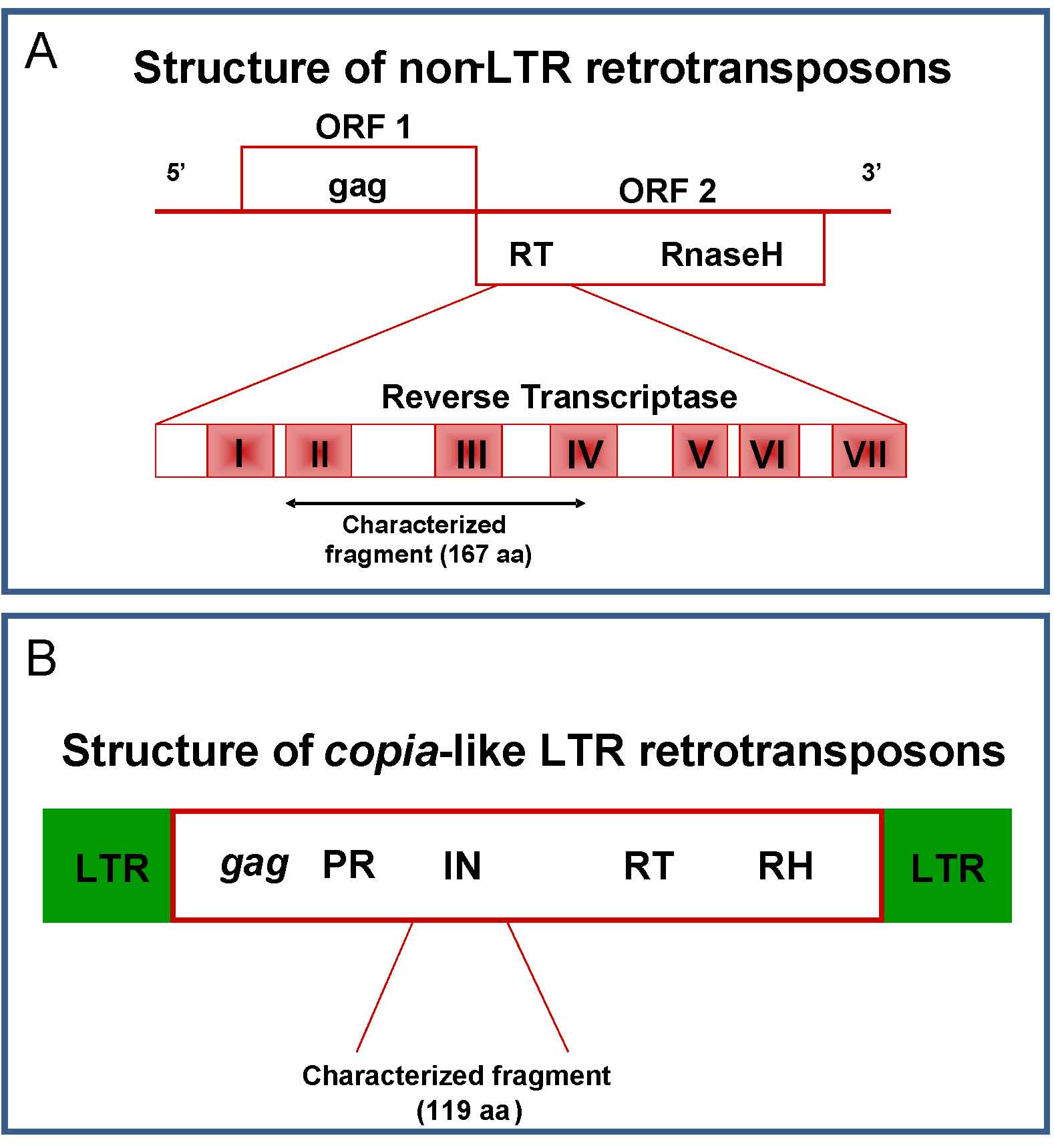

The SCAR strategy applied to RAPD markers allowed the molecular identification of retrotransposable elements in beech. Homology searching in databases confirmed that the cloned and sequenced RAPD marker RF2/35 is homologous to a class I LTR retroelement. As reported in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5, the identified fragment contains the integrase and endonuclease domains of the pol polyprotein coding gene of a LTR retrotransposon. The homology obtained between the original beech sequence and the BLAST best-hit sequences also allowed ascribing the identified retrotransposon to the copia-like type. The characterized fragment contains only coding regions, suggesting a possible integrity of the identified retrotransposable element.

Fig. 4 - Molecular identification of beech LTR retroelement. ClustalW alignment of the original sequence form F. sylvatica and a selection of best hit homologous sequences obtained by database searching. The integrase and endonuclease domain of the pol gene are highlighted by arrows. Grey shading of aminoacids identifies site identity.

Fig. 5 - Schematic representation of non-LTR LINE (A) and copia-like LTR (B) retrotransposable elements. Characterized fragments are highlighted.

On the contrary only a part (501 bp) of the RAPD marker 1253/1 showed high homology to characterized retrotransposons, suggesting that ORFs fragmentation occurred for this element in beech, as often reported for truncated LINE elements ([25]). Nevertheless, the identified fragment contains three domains of the LINE non-LTR retrotransposable element reverse transcriptase (Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 - Molecular identification of beech non-LTR LINE retrotransposable elements. ClustalW alignment of the original sequence from F. sylvatica and a selection of best hit homologous sequences obtained by database searching. The three domains of the identified reverse transcriptase are highlighted by boxes. Grey shading of aminoacids identifies site identity.

The original sequences of the two identified retrotransposable elements are deposited in GeneBank under the accession number AF405557.1 and AF405555.1.

The identification of partial sequences of retrotransposable elements in broadleaf forest tree species can be useful for studies of genome evolution and for paving the way to new diversity screenings approaches already implemented in crop or model species ([38], [24]).

Polymorphism of beech retrotransposable elements

The analysis of the polymorphism of beech retrotransposable elements was carried out with two strategies: i) sequence analysis of cloned fragments and ii) CAPs analysis of amplified fragments (Fig. 3).

Through the cloning and sequencing of amplification fragment obtained with specific primers, the characterization of the retroelement diversity in different beech genotypes was possible. As reported in Tab. 1, the LTR retrotransposable element resulted polymorphic in each genotype. The level of diversity is noticeable, showing, at nucleotide level, 22 (out of 357) polymorphic sites, with 12 missense mutations. It is important to stress that all the sequenced LTR retrotransposons maintain a putatively functional protein sequence (at least for the characterized fragment) suggesting a possible active status of this class of retrotransposons in beech, as often reported for this type of retrotransposable elements in many species ([39]). The sequences polymorphism of the 5 different clones from the same genotypes (data not shown) also allows concluding that this element forms a multi-copy family inside beech genome in agreement with the viral-quasi species theory of the evolution of retrotransposable elements ([5]).

Tab. 1 - Nucleotide and deduced protein sequence polymorphisms shown by the LTR retrotransposable elements belonging to different F. sylvatica genotypes. The nucleotide variations responsible of the missense mutations is highlighted in block capitals and the correspondent aminoacid variation is reported in the same column (lowermost part of the table). Dot represents site identity. Beech genotypes are reported with the name of the geographical provenance.

| F. sylvatica genotypes |

Nucleotide sequence variable site number (total sequence length 357 nucleotides) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39 | 44 | 48 | 55 | 77 | 84 | 87 | 115 | 158 | 177 | 181 | 201 | 202 | 210 | 211 | 223 | 225 | 230 | 233 | 252 | 266 | 318 | |

| - | Variable nucleotides | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Foresta Umbra | c | T | a | t | G | g | c | G | G | t | C | c | G | c | A | T | g | T | T | G | G | t |

| Mt. Etna | t | A | c | c | . | . | a | A | . | a | . | t | . | . | G | C | . | . | . | . | . | c |

| Madonie | . | . | . | c | A | a | . | . | . | c | . | . | . | . | G | C | a | . | . | . | . | . |

| Sila | t | . | c | c | . | . | a | . | A | . | G | t | A | t | G | C | . | C | A | T | A | c |

| Irpinia | . | . | . | c | A | a | . | . | . | c | . | . | . | . | G | C | a | . | . | . | . | . |

| - | Protein sequence variable site number (total sequence length 119 aa) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| - | - | 15 | - | - | 26 | - | - | 39 | 53 | - | 61 | - | 68 | - | 71 | 75 | - | 77 | 78 | 84 | 89 | - |

| - | Variable aminoacids | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Foresta Umbra | - | L | - | - | G | - | - | E | G | - | P | - | G | - | K | W | - | I | V | M | R | - |

| Mt. Etna | - | H | - | - | . | - | - | K | . | - | . | - | . | - | E | R | - | . | . | . | . | - |

| Madonie | - | . | - | - | E | - | - | . | . | - | . | - | . | - | E | R | - | . | . | . | . | - |

| Sila | - | . | - | - | . | - | - | . | D | - | A | - | E | - | E | R | - | T | D | I | Q | - |

| Irpinia | - | . | - | - | E | - | - | . | . | - | . | - | . | - | E | R | - | . | . | . | . | - |

The experimental approach reported above also allowed determining the polymorphism of the non-LTR element. The diversity of the non-LTR retrotransposon sequences from different beech genotypes (see Supplementary material) is distinctly higher than that the one reported for the LTR element, with 99 polymorphic sites out of 501 nucleotides. In this case the presence of nonsense mutation, the reported level of diversity and the abrupt ending of the coding region of the characterized fragment suggest that the identified class I TE is inactive for ORFs fragmentation and subjected to genetic drift ([7]).

The polymorphism shown by the reverse transcriptase fragment of the LINE element suggested the development of a Cleaved Amplified Polymorphism (CAP) approach in order to study the genetic diversity of the element itself and, considering its putative neutrality, the diversity of beech genotypes and populations. The restriction analysis (Tab. 2) pointed out that the specific amplicon of the reverse transcriptase constitutes, for each genotype, a family of fragments, thus demonstrating, in accordance with the cloned sequence analysis, that also the LINE element represents a multi-copy quasi-species inside each beech genome. Using on 90 beech genotypes the simple and time saving CAP approach with only one restriction enzyme, 12 alleles (sensu lato) were identified (Tab. 2). Each beech individual showed at least and simultaneously 4 alleles. The CAP pattern allowed recognizing 6 alleles already expected from the results of the in silico restriction analysis of the sequenced fragment, demonstrating the reproducibility of the approach, and 6 alleles not previously described. This also suggests that the polymorphism identified is an underestimation of the real diversity of the retrotransposon quasi-species, since the cloning strategy did not allow characterizing all the alleles in each genotype.

Tab. 2 - Results of the Cleaved Amplified Polymorphism analysis on the non-LTR retrotransposable elements amplified fragment (total fragment length: 501 bp = 167 aa). Among the obtained alleles, 6 were already expected from in silico restriction analysis of sequenced fragments.

| Allele | Restriction fragment length (bp) | Comments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 135 | 300 | 26 | 7 | 34 | - | Expected by sequences restriction analysis and obtained with CAPs approach |

| 2 | 200 | 100 | 135 | 14 | 53 | - | |

| 3 | 200 | 100 | 33 | 102 | 14 | 53 | |

| 4 | 135 | 164 | 135 | 14 | 19 | 34 | |

| 5 | 135 | 201 | 98 | 26 | 7 | 34 | |

| 6 | 135 | 164 | 135 | 33 | 34 | - | |

| 7 | 448 | 19 | 34 | - | - | - | Obtained with CAPs approach |

| 8 | 200 | 135 | 114 | 53 | - | - | |

| 9 | 120 | 15 | 300 | 26 | 7 | 34 | |

| 10 | 135 | 164 | 147 | 19 | 34 | - | |

| 11 | 230 | 70 | 33 | 100 | 14 | 53 | |

| 12 | 135 | 333 | 34 | - | - | - | |

From the bioinformatic analysis of the available sequences is also easy to predict that the use of different restriction enzymes could produce an impressive number of markers in an easy and time-saving way. The approach proposed here represents a new method of exploiting the diversity of retrotransposable elements, for genetic variability screening which can complement already developed strategies as the S-SAP ([41]), the IRAP and the REMAP ([14]) approaches.

Conclusions

In the present work the identification of retrotransposable elements in the genome of the broadleaved forest tree species Fagus sylvatica is reported. Since retrotransposons are fundamental in the evolution of plants genome, gene duplication, transcription regulation and epigenetic effects, the identification of these peculiar genetic elements in beech can help the understanding of such processes in non model species, along with the increasing availability of woody perennial species genomes such as poplar ([34]) and grape ([13]). The results of the molecular characterization confirm that in beech retrotransposable elements build up multi-copy families that can be used for molecular fingerprinting.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Donatella Paffetti

Raffaello Giannini

Dept. of Environmental and Forestry Technologies and Sciences, University of Florence, v. S. Bonaventura 13, I-50145 Florence (Italy).

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Emiliani G, Paffetti D, Giannini R (2009). Identification and molecular characterization of LTR and LINE retrotransposable elements in Fagus sylvatica L.. iForest 2: 119-126. - doi: 10.3832/ifor0501-002

Paper history

Received: Feb 04, 2009

Accepted: Mar 25, 2009

First online: Jun 10, 2009

Publication Date: Jun 10, 2009

Publication Time: 2.57 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2009

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 66900

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 55874

Abstract Page Views: 4062

PDF Downloads: 5848

Citation/Reference Downloads: 60

XML Downloads: 1056

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 6112

Overall contacts: 66900

Avg. contacts per week: 76.62

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2009): 3

Average cites per year: 0.18

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Patterns of genetic diversity in European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) at the eastern margins of its distribution range

vol. 10, pp. 916-922 (online: 10 December 2017)

Research Articles

Genetic diversity of core vs. peripheral Norway spruce native populations at a local scale in Slovenia

vol. 11, pp. 104-110 (online: 31 January 2018)

Review Papers

Genetic diversity and forest reproductive material - from seed source selection to planting

vol. 9, pp. 801-812 (online: 13 June 2016)

Research Articles

Seedling emergence capacity and morphological traits are under strong genetic control in the resin tree Pinus oocarpa

vol. 17, pp. 245-251 (online: 16 August 2024)

Research Articles

Genetic variation and heritability estimates of Ulmus minor and Ulmus pumila hybrids for budburst, growth and tolerance to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi

vol. 8, pp. 422-430 (online: 15 December 2014)

Research Articles

Patterns of genetic variation in bud flushing of Abies alba populations

vol. 11, pp. 284-290 (online: 13 April 2018)

Research Articles

Age trends in genetic parameters for growth and quality traits in Abies alba

vol. 9, pp. 954-959 (online: 07 July 2016)

Research Articles

Comparison of genetic parameters between optimal and marginal populations of oriental sweet gum on adaptive traits

vol. 11, pp. 510-516 (online: 18 July 2018)

Research Articles

Comparison of range-wide chloroplast microsatellite and needle trait variation patterns in Pinus mugo Turra (dwarf mountain pine)

vol. 10, pp. 250-258 (online: 11 February 2017)

Research Articles

Clonal structure and high genetic diversity at peripheral populations of Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz.

vol. 9, pp. 892-900 (online: 29 May 2016)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword