Maximizing growth of Acacia confusa through native plant growth-promoting bacterial inoculation and seed pelleting for revegetation in landslide areas

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 19, Issue 1, Pages 28-37 (2026)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor4082-018

Published: Jan 11, 2026 - Copyright © 2026 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Revegetation in landslide-affected areas is challenging due to the extensive terrain and poor soil quality. Applying bacteria with plant growth-promoting (PGP) traits offers a promising approach to support plant growth in these disturbed regions. This study aimed to investigate seed enhancement methods by selecting bacterial strains and developing seed pellet mixtures to facilitate revegetation processes. Specifically, we focused on enhancing the germination rate and growth of Acacia confusa through seed pretreatment and inoculation with native bacteria in the growing substrate for pot cultivation and seed pellets. Fifty-four native bacterial strains were isolated from the rhizosphere and endo-rhizosphere of A. confusa growing in the Dadu plateau, Taiwan. Isolates were tested for their ability to stimulate or inhibit the growth of A. confusa seeds on Petri dishes. Sixteen isolates with germination parameters significantly differing from the control were selected for pot tests. 16S rDNA gene sequencing showed that most strains belonged to the genus Bacillus and exhibited one or more PGP traits. Seedling growth parameters were significantly improved by inoculating the substrate with isolates A2TP3 (Bacillus proteolyticus) and A2SP5 (Lysinibacillus sphaericus), which exhibited strong abilities to enhance shoot growth and were therefore selected for evaluation in seed pellet production. Seed germination after inoculation in seed pellets varied with the mixture used. This study demonstrated that bacterial inoculation is a promising bio-inoculant for A. confusa on specific substrates; however, further experiments on seed pelleting mixtures are still needed.

Keywords

Acacia confusa, Bacterial Inoculation, Plant Growth-Promoting (PGP) Bacteria, Revegetation, Seed Pellets

Introduction

Taiwan’s steep mountain slopes and heavy summer typhoon rains make them susceptible to landslides ([9]). These landslides occur across vast terrains and vary greatly in scale, often damaging natural landscapes and posing serious risks to residents in mountainous regions. Revegetation with native woody plants is one approach to landslide rehabilitation ([55]). However, seed germination and the initial establishment of seedlings in landslide areas are often slow and unreliable due to poor soil quality ([37]) and seed dormancy ([15]).

Acacia confusa Merr. (Fabaceae), commonly known as Taiwan acacia, is a leguminous species used for reforestation of highly eroded soils and landslide-prone areas across the island ([56], [29]). This fast-growing, woody perennial tree is native to Taiwan ([28]). It is widely distributed across diverse habitats, including infertile soils, rocky plains, hills, hard clay, and silt ([4]). However, Acacia seeds have hard seed coats that delay germination ([15]), and it is essential to support the growth and survival of seedlings after germination.

Many studies applied various methods to enhance seed germination ([19]). These technologies include seed pretreatment ([25], [15]), seed inoculation with bacterial strains ([13], [29]), and seed pelleting ([6], [30]).

Seed pretreatment is a widely used technique for breaking seed dormancy ([50]). According to Nxumalo et al. (unpublished), treating A. confusa seeds with concentrated H2SO4 or soaking them in water at 100 °C improved germination rates to 92% and 78%, respectively. However, handling concentrated H2SO4 in large quantities can be challenging. In contrast, hot-water treatment is a simpler and more economical method for breaking the dormancy of A. confusa seeds (Nxumalo et al., unpublished).

Bacterial inoculation is a strategy to enhance seed germination and promote plant growth. Bacteria support plant development by fixing nitrogen, solubilizing phosphate, and producing compounds such as Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA), hydrogen cyanide (HCN), and siderophores. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria, in particular, stimulate nodule formation, thereby increasing nitrogen uptake in plants ([17], [36]). Therefore, bacterial inoculation is a promising approach for improving soil fertility in degraded areas. However, studies involving symbionts specific to A. confusa remain scarce.

Seed pellets, or seed balls, are nearly spherical structures containing various materials that modify the seed’s size, mass, and shape. This technique facilitates the handling of tiny, irregularly shaped seeds ([2]). They provide numerous benefits, such as protecting seeds from predators, including rodents and birds, by enclosing them within pellets. Additionally, seed pellets are convenient for delivering biological treatments, including bacterial inoculants ([6]).

Many studies have examined the effects of pretreatments ([15]) or bacterial inoculation ([31], [29], [7], [27]) on the germination and growth of Acacia species. However, no study has examined the potential of combining native bacterial inoculation with seed pelleting methods for Acacia species used in revegetation. This study aims to screen native plant growth-promoting (PGP) bacterial strains for A. confusa and to explore the effectiveness of seed pelleting in enhancing its germination. We isolated and evaluated native bacterial strains to improve A. confusa seed germination and growth in both growing substrate for pot cultivation and pelleted seeds. Bacterial strains isolated from the soil and root nodules of adult trees that promoted growth in pots were then used to seed pellets. Germination rates of inoculated and uninoculated seeds were compared in different pellet mixtures.

Materials and methods

Native bacterial isolation

Soil and root nodules were collected from A. confusa plantation stands at three sites on the Dadu Plateau, Taiwan (Site A1: 24° 08′ 34.9″ N, 120° 34′ 53.1″ E; Site A2: 24° 09′ 11.4″ N, 120° 34′ 11.0″ E; and Site A3: 24° 09′ 19.4″ N, 120° 35′ 50.7″ E), on 19 February 2020. Soil samples near the roots of mature A. confusa were collected randomly at each site from two depths: 0-15 cm and 15-30 cm. Soil properties for each site are listed in Tab. S1 (Supplementary materials).

For rhizobacterial isolation, approximately 10 g of each soil sample was added to a conical flask containing 8 mL of sterile water. The flasks were shaken for 30 minutes on an orbital shaker at 27 °C. Then, 2 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was transferred into five tubes using sterile 10 mL pipettes under aseptic conditions. The soil solution from each sample was diluted to 10-6 in sterile water. Using the spread plate method, a 100 µL aliquot of each diluted culture was spread over the surface of the nutrient agar medium. Single bacterial colonies were labeled based on location (A1, A2, A3), soil depth (T for topsoil and S for subsoil), and plate number (P1, P2, etc.).

To isolate root nodule bacteria, roots were cleaned and sterilized with ethanol and sodium hypochlorite ([29]), then cut into small pieces (3.5 cm). After serial dilution, the 10-4 and 10-6 dilutions from the root nodules were streaked onto yeast extract mannitol agar (YEMA) and nutrient agar (NA) plates. Following five days of incubation at 28 °C, single colonies were characterized morphologically. Isolates were labeled according to location (A1, A2, A3), medium used for isolation (NA/YEMA), and plate number (P1, P2, etc.).

Fifty-four isolates, comprising thirty-five rhizobacterial strains and nineteen endophytes, were isolated from the A. confusa plantation. These isolates were then assessed for their growth-promoting abilities in A. confusa; only 16 isolates showed significant effects on growth parameters in Petri dish assays and were subsequently used in further experiments.

Native bacterial identification

The bacterial isolates were identified using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Total DNA was extracted using the Ultraclean® Microbial DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Genomic DNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the universal primer pair 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) to amplify a ~1500 bps region. PCR was performed on a Thermal Cycler 2720TM (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the following cycling conditions: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 minute, 52 °C for 1.5 minutes, and a final extension at 72 °C for 3 minutes ([11]). DNA fragments were identified using electrophoresis at 60 V for 24 minutes, examined under UV light, and photographed with the Molecular Imaging System (Gel Logic GL 212 Pro®, Carestream Health, Inc., New Haven, CT, USA) to determine fragment sizes.

Gene sequences were analyzed using Clustal W multiple sequence alignment in BioEdit software ([49]) and compared with highly similar rRNA sequences on the National Center for Biotechnology Information NCBI EzTaxon server (⇒ https://www.ezbiocloud.net/). Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA X ([26]), with branch confidence assessed using 1.000 bootstrap replicates with the neighbor-joining method ([48]).

Plant growth promotion (PGP) traits

Phosphate-solubilizing ability

Bacterial colonies were screened for phosphate-solubilizing ability on Pikovskaya (PKV) agar medium supplemented with insoluble tricalcium phosphate. Bacterial strains were inoculated at the center of medium plates (divided into four sections for replication) using sterile tips and incubated at 30 °C for three days. Colonies exhibiting visible, transparent halos around bacterial growth were considered phosphate solubilizers ([41]).

Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production

Approximately 0.5 mL of each bacterial strain solution was inoculated into test tubes containing 5 mL of nutrient broth (NB, HiMedia Lab Ltd., Maharashtra, India) or yeast extract mannitol (YEM) medium and 0.5 mL of 5 g L-1 L-tryptophan (prepared from a filter-sterilized 5 g L-1 stock). The test tubes were then incubated at 28 °C for 42 hours on a rotating shaker at 180 rpm. Cell density was measured at 600 nm. Cells were separated from the medium by centrifugation at 5500 g for 10 minutes, and 1 mL of the supernatant was transferred into new test tubes containing 4 mL of Van Urk-Salkowski color reagent (prepared with 150 mL of concentrated H2SO4, 250 mL of distilled H2O, and 7.5 mL of 0.5 M FeCl3·6H2O). IAA levels were measured at 530 nm absorbance using a spectrophotometer after incubation in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes. A pink coloration of the supernatant indicated IAA production ([40], [16]).

Nitrogen-fixing ability

Nitrogen-fixing ability was evaluated for each bacterial strain using the acetylene reduction assay ([43]). This method detects nitrogenase activity by measuring ethylene (C2H4) production, which indicates the bacterium’s potential to fix nitrogen. Ethylene production was measured in triplicate for each isolate, with an uninoculated control, using a gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector (Model 163, HITACHI, Chiyoda City, Japan). The carrier gas (nitrogen) flow rate was set to 35 mL h-1, with the flame ionization detector temperature at 110 °C and the Porapak N column (1 m × 2 mm) maintained at 80 °C.

Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) production

HCN production was assessed by inoculating flasks with 100 mL of nutrient broth or YEM medium supplemented with 4.4 g L-1 glycine. A sterile Whatman filter paper strip dipped in a picric acid solution (0.5% picric acid in 2% sodium carbonate) was attached to the neck of each flask. The flasks were then sealed with Parafilm® and incubated on a rotary shaker at 140 rpm for four days. A color change in the filter paper strip from yellow to light brown, brown, or brick red was recorded as a positive (+) result, while no color change indicated a negative (-) reaction ([1]).

Siderophore production

The ability of the bacterial isolates to produce siderophore (iron-chelating compounds) was tested using Chrome Azurol S (CAS) medium ([7]) prepared by mixing CAS blue dye ([51]) with PIPES (Piperazine-1.4-bis[2-ethanesulfonic acid]) agar. Bacterial isolates were first cultured on NA or YEMA plates and then spot-inoculated onto CAS plates. The appearance of an orange, yellow, or violet halo around the bacterial colonies indicated positive siderophore production.

Preliminary Petri dish experiment

Seeds were sterilized by soaking in 75% ethanol for 2 minutes, then rinsed five times with sterile water. These seeds were then divided into two groups: (i) a pretreated group exposed to hot water (100 °C for 20 minutes) and (ii) a non-pretreated group. For each bacterial strain, three plates contained pretreated seeds and three plates contained non-pretreated seeds. A total of sixteen bacterial cultures were incubated at 28 °C for 5 days. For inoculation, 2 mL of each cell suspension, adjusted to an optical density (A600) of 0.1 using a Genesys™ 30 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), was added to Petri dishes containing 10 seeds each. The control group received 2 mL of sterile water, replacing the bacterial inoculum.

Shoot length was measured from the collar region to the tip of the bud, while root length was measured from the base of the shoot to the tip of the longest root. Germination was defined as the emergence of the radical tip and was recorded for up to 10 days ([47]). Germination percentage and vigor index were calculated according to the methods of Sun et al. ([47] - eqn. 1):

where GP is the germination percentage, Nd10 is the number of seeds that germinated in 10 days, and Ntot is the total number of seeds on the plate.

To achieve a normal distribution, germination percentage data (GP) were transformed using the angular transformation method ([10]), which stabilizes the variance of proportion data, as follows (eqn. 2):

The output was converted from radians to degrees for ease of interpretation ([32]).

The vigour index was calculated following Sun et al. ([47] - eqn. 3):

where VI is the vigor index, SL is the total seedling length, and tGP is the transformed germination percentage (see eqn. 2).

Pot culture experiment

For the pot experiment, ten inoculated A. confusa seeds per bacterial isolate were prepared in Petri dishes and grown until the seedlings reached a shoot length of 5 cm. These seedlings were transplanted into 1 L pots containing 0.5 kg of sterile peat, which had been autoclaved for 1 hour and 20 minutes over two consecutive days. The chemical properties of the peat were as follows: pH 6.0, EC 700 µS cm-1, organic matter (OM) 20%, potassium (K) 27.17 mg kg-1, calcium (Ca) 398.65 mg kg-1, sodium (Na) 16.78 mg kg-1, magnesium (Mg) 46.37 mg kg-1. Peat was used instead of landslide soil to evaluate the potential of these native strains in a commercial growing substrate.

A completely randomized pot experiment was conducted to evaluate the selected bacterial isolates for their ability to promote the growth of A. confusa. Each isolate had 10 replicates: 5 pots with seedlings grown from pretreated seeds and 5 pots with seedlings grown from non-pretreated seeds. Immediately after transplanting, a 5 mL suspension of each isolate (A600 = 0.1) was applied to five holes in the media around each seedling. The inoculation was repeated two weeks later to promote colonization. Uninoculated seeds served as controls. The experiment was conducted in an open area (rooftop) at the International Agriculture Building, National Chung Hsing University, lasting 24 weeks (October 15, 2020 to June 2, 2021). Pots were irrigated regularly and uniformly throughout the experiment. After eight weeks, the inoculated bacteria were re-isolated and examined to confirm their continued presence in the plant pots.

Growth parameters, including shoot length, were measured every four weeks. Plant survival and root length were measured at the end of the experiment, 24 weeks after planting. Root volume was determined using the water-displacement method ([38]).

Chlorophyll content

Chlorophyll measurements were taken on the leaves (phyllodes) at 4-week intervals until the 24th week, using a chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502, Minolta, Japan) to assess chlorophyll content in situ.

Seed pellet experiment

The seed pellet substrates tested in this study included clay, sawdust, and biochar. The clay soil was collected from a landslide area in Taichung. Sawdust, purchased from the Jinfeng Wood Products company, consisted of a mixture of coniferous species, including Western Red Cedar, Yellow Cedar, Spruce, and Douglas Fir. Biochar was produced by pyrolyzing rice husks at approximately 600 °C and 300 °C.

Bulking materials were autoclaved for 2 hours before use. Organic material was then mixed with clay in the following ratios to form four treatments: Treatment (T1), clay: organic material (mixture of compost and soil) (1:1); Treatment 2 (T2), clay: organic material (1:1) with the addition of 1% biochar (pyrolyzed at c. 600 °C); Treatment (T3), clay: organic material (1:1) with the addition of 1% biochar (pyrolyzed at c. 300 °C); Treatment 4 (T4), clay: organic material (1:1) with the addition of 10% sawdust. A 16% v/v stock solution of an agglomerating agent (diluted with water) was obtained from the Japan Ryukyu Red Soil Prevention Company to bind the bulking materials.

In the seed pellet experiment, two bacterial strains were selected for their plant growth-promoting performance to evaluate their efficacy in seed pellets. For each strain, two 1-liter beakers were prepared: one containing 50 g of seeds pretreated at 100 °C for 20 minutes and the other containing 50 g of untreated seeds. Then, 2 mL of bacterial inoculant suspension (A600 = 0.1) was added to the respective beakers. Seeds were soaked in the bacterial suspension for 6 hours and then spread on disinfected kitchen paper towels to dry.

This mixture of seeds and bulking materials (T1-T4) was then placed in a seed pelleting machine, which produced pellets 5 cm in diameter. Black PVC seedling trays (490 × 190 × 25 mm, length × width × depth) were sterilized in 70% sodium hypochlorite solution and lined with filter paper, with one pellet placed in each hole. The containers were incubated at 28 °C for 10 days, and sterilized distilled water was used to water the seed pellets once daily.

To determine the chemical properties of the materials used, solid bulking materials were mixed with distilled water at a 1:2 w/v ratio (1 g of solid bulking material per 2 mL of H2O) and stirred thoroughly with a magnetic stirrer. Three replicates of each material were tested for pH and electrical conductivity (EC), with pH measured using a glass electrode pH meter and EC determined using an electrical conductivity meter. Mean pH values (± standard deviation, SD) were as follows: organic material, 6.5 ± 0.1; biochar (300 °C), 7.2 ± 0.1; biochar (600 °C), 7.8 ± 0.5; sawdust, 6.9 ± 0.1; clay, 6.3 ± 0.6; adhesive, 6.3 ± 0.3; Treatment 1, 6.8 ± 0.2; Treatment 2, 7.1 ± 0.3; Treatment 3, 7.3 ± 0.3; Treatment 4, 6.7 ± 0.1. The EC values (µS cm-1) were as follows: organic material, 361 ± 5.1; biochar (300 °C), 673 ± 1.4; biochar (600 °C), 303 ± 1.9; sawdust, 56.4 ± 0.1; clay, 421 ± 1.5; adhesive, 396 ± 0.8; Treatment 1, 180 ± 0.6; Treatment 2, 520 ± 0.8; Treatment 3, 940 ± 1.0; Treatment 4, 440 ± 1.1. Water-holding capacity was determined according to Somasegaran & Hoben ([46]). The physiological analysis conducted at the end of the experiment was the germination percentage (GP - see eqn. 1), assessed 10 days after the seed pellets were incubated.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using ANOVA (one-way and two-way ANOVA). When significant between-group effects were found, Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was used for post-hoc analysis, with p < 0.05. Before ANOVA, the homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene’s test (α = 0. 05). If the homogeneity assumption was violated, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used, followed by pairwise comparisons with Dunn’s test. Seed germination percentages were arcsine-transformed before analysis. GraphPad Prism ver. 10.3 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and SPSS ver. 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) were used for statistical analyses. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using MEGA 7.

Results

Native bacterial isolation and identification

A preliminary test identified 16 bacterial isolates that exhibited significant changes in various growth parameters relative to the control (Tab. 1). The 16 isolates were subsequently selected for further assessment in the pot experiment and subjected to 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis using primers 27F and 1492R. Tab. 1 lists the closest species from the NCBI database, whereas Fig. S1 (Supplementary material) shows the phylogenetic relationships between these isolates.

Tab. 1 - 16S rDNA sequence analysis and PGP traits of 16 bacterial isolates selected for the pot experiment with A. confusa seeds. Values labelled with different letters within a column significantly (p < 0.05) differ after Tukey’s HSD tests. Isolate codes: endophytes (e, in superscript) were coded based on the location where nodules were collected, the medium used to culture the bacterial strains, and the plate number; rhizobacteria (r, in superscript) were coded by soil collection location, soil depth (T for topsoil and S for subsoil), and plate number. (IAA): Indole-3-Acetic Acid; (HCN): Hydrogen Cyanide; (+): the isolate possesses the function; (-): the isolate lacks the function; (nd): the isolate did not grow in the Chrome Azurol medium. (†): isolates used in the seed pellet experiments.

| Isolate code |

Closest relative description |

Similarity (%) |

Phosphorous solubilization |

IAA (mg L-1) |

N fixation (nmol C2H4 hr-1) |

HCN | Siderophore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1TP2r | Lysinibacillus sphaericus | 99 | - | 9.45 ± 0.01 b | -0.03 ± 0.06 a | + | - |

| A1TP3r | Bacillus proteolyticus | 99 | + | 4.40 ± 0.03 a | 0.02 ± 0.32 b | + | nd |

| A1SP2r | Bacillus siamensis | 96 | - | 3.07 ± 0.15 a | -0.03 ± 0.21 a | + | nd |

| A2SP1r | Lysinabacillus sp. | 100 | + | 23.61 ± 0.20 c | -0.01 ± 0.10 a | - | nd |

| A2SP2r | Bacillus siamensis | 96 | - | 6.46 ± 0.08 ab | 0.05 ± 0.12 b | - | nd |

| A2SP5r (†) | Lysinibacillus sphaericus | 99 | - | 20.15 ± 0.01 c | -0.02 ± 0.02 a | - | + |

| A2SP7r | Arthrobacter alkaliphilus | 98 | + | 7.39 ± 0.04 ab | -0.02 ± 0.01 a | - | - |

| A2TP3r (†) | Bacillus proteolyticus | 99 | + | 23.88 ± 0.12 c | 0.33 ± 0.04 c | - | nd |

| A2TP5r | Brevibacillus formosus | 99 | + | 14.94 ± 0.08 b | 0.33 ± 0.03 c | - | + |

| A3TP1r | Lelliottia jeotgali | 98 | + | 15.01 ± 0.16 b | 0.07 ± 0.01 b | - | + |

| A2NA3-1e | Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens | 99 | + | 6.07 ± 0.12 ab | 0.33 ± 0.01 c | - | + |

| A2NA3-2e | Bacillus proteolyticus | 99 | + | 13.38 ± 0.09 b | 0.03 ± 0.12 b | + | nd |

| A2YEMA2-1e | Bacillus proteolyticus | 99 | - | 6.11 ± 0.22 ab | 0.03 ± 0.15 b | - | nd |

| A2YEMA6-1e | Bacillus tequilensis | 99 | - | 36.64 ± 0.03 d | 0.05 ± 0.21 b | - | - |

| A2YEMA8-1e | Bacillus megaterium | 99 | - | 50.37 ± 0.12 e | 0.18 ± 0.07 b | + | + |

| A2YEMA8-2e | Pseudomonas alloputida | 96 | + | 34.28 ± 0.15 d | 0.05 ± 0.09 b | + | nd |

Plant growth promotion (PGP) traits

Nine isolates exhibited phosphate-solubilizing ability, with six rhizospheric and three endophytic bacteria (Tab. 1). All isolates produced IAA in the presence of tryptophan, ranging from 3.07 to 50.37 mg L-1, with the isolate A2YEMA8-1 (Bacillus megaterium) showing the highest IAA production (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.001 - Tab. 1). Eleven isolates tested positive for nitrogen fixation (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.003), and six isolates were positive for hydrogen cyanide (HCN) production. Approximately half of the strains did not grow on the Chrome Azurol medium (Tab. 1), indicating a lack of siderophore production.

Preliminary Petri dish experiment

Tab. 2and Tab. 3present the results of germination and growth of pretreated and non-pretreated seeds in Petri dishes, respectively. For 16 isolates, some significant effects on germination or growth parameters were observed, including 10 rhizospheric strains and 6 endophytes. For example, bacterial inoculation significantly affected the shoot length of seedlings grown from pretreated (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.003 - Tab. 2) and non-pretreated seeds (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.004 - Tab. 3). Strains that showed significant effects on germination or growth parameters compared to the control were selected for the subsequent pot experiment.

Tab. 2 - Effect of inoculation with native bacterial isolates on the germination and growth of A. confusa pretreated seeds in Petri dishes. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from 5 replicates per treatment. Means in columns labelled with different letters are significantly (p < 0.05) different after Tukey’s HSD test. (r): rhizobacteria; (e): endophytes; (NT): non-transformed data; (T): transformed data (see eqn. 2). (†): isolates used in the seed pellet experiments.

| Isolate code |

Shoot Length (cm) |

Root Length (cm) |

Shoot/root ratio |

Shoot Weight (g) |

Germination percentage (%) | Vigor Index (cm) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT | T | ||||||

| Control | 1.04 ± 0.01 a | 1.26 ± 0.02 a | 1.6 | 0.04 ± 0.08 a | 43.3 a | 41.1 | 135.6 |

| A1TP2r | 2.68 ± 0.01 a | 2.19 ± 0.08 a | 1.2 | 0.05 ± 0.22 a | 90.0 c | 71.6 | 348.7 |

| A1TP3r | 1.29 ± 0.03 a | 0.15 ± 0.12 b | 8.6 | 0.09 ± 0.08 a | 70.0 b | 56.8 | 81.8 |

| A1SP2r | 6.69 ± 0.04 b | 1.89 ± 0.22 a | 3.5 | 0.10 ± 0.08 a | 73.3 b | 58.9 | 505.4 |

| A2SP1r | 4.78 ± 0.01 ab | 3.30 ± 0.05 a | 1.4 | 0.07 ± 0.05 a | 90.0 c | 71.6 | 578.5 |

| A2SP2r | 4.67 ± 0.01 ab | 1.44 ± 0.10 a | 3.2 | 0.07 ± 0.09 a | 70.0 b | 56.8 | 347 |

| A2SP5r (†) | 3.79 ± 0.05 a | 2.06 ± 0.07 a | 1.8 | 0.07 ± 0.09 a | 83.3 b | 65.9 | 385.5 |

| A2SP7r | 3.78 ± 0.09 a | 2.11 ± 0.05 a | 1.8 | 0.07 ± 0.06 a | 90.0 c | 71.6 | 421.7 |

| A2TP3r (†) | 5.67 ± 0.09 b | 0.31 ± 0.09 b | 18.2 | 0.02 ± 0.09 a | 43.3 a | 41.1 | 245.8 |

| A2TP5r | 3.50 ± 0.03 a | 0.05 ± 0.12 b | 70 | 0.06 ± 0.12 a | 63.0 a | 52.5 | 186.4 |

| A3TP1r | 6.33 ± 0.07 b | 1.28 ± 0.15 a | 4.9 | 0.10 ± 0.13 a | 80.0 b | 63.4 | 482.5 |

| A2NA3-1e | 9.19 ± 0.03 b | 4.40 ± 0.01 a | 2.1 | 0.20 ± 0.10 a | 100.0 c | 90 | 1223.1 |

| A2NA3-2e | 11.54 ± 0.01c | 2.56 ± 0.06 a | 4.5 | 0.11 ± 0.01 a | 93.3 c | 75 | 1057.5 |

| A2YEMA2-1e | 6.57 ± 0.01 b | 1.70 ± 0.03a | 3.9 | 0.10 ± 0.03 a | 93.3 c | 75 | 620.3 |

| A2YEMA6-1r | 6.28 ± 0.08 b | 2.88 ± 0.05 a | 2.2 | 0.03 ± 0.00 a | 86.7 b | 68.6 | 628.4 |

| A2YEMA8-1e | 5.74 ± 0.01 b | 1.00 ± 0.08 a | 5.7 | 0.08 ± 0.04 a | 76.6 b | 61.1 | 411.8 |

| A2YEMA8-2e | 5.58 ± 0.04 b | 1.87 ± 0.09 a | 3 | 0.09 ± 0.06 a | 80.0 b | 63.4 | 472.3 |

Tab. 3 - Effect of inoculation with native bacterial isolates on the germination and growth of A. confusa non-pretreated seeds in Petri dishes. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from 5 replicates per treatment. Means in columns labelled with different letters are significantly (p < 0.05) different after Tukey’s HSD test. (r) rhizobacteria; (e): endophytes; (NT): non-transformed data; (T): transformed data (see eqn. 2). (†): isolates used in the seed pellet experiments.

| Isolate code |

Shoot Length (cm) |

Root Length (cm) |

Shoot/root ratio |

Shoot Weight (g) |

Germination percentage (%) | Vigor Index (cm) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT | T | ||||||

| Control | 0.71 ± 0.01 a | 0.81 ± 0.01 a | 0.9 | 0.02 ± 0.02 a | 16.6 a | 24.0 | 0.88 |

| A1TP2r | 1.17 ± 0.02 a | 0.67 ± 0.02 a | 1.8 | 0.02 ± 0.03 a | 16.7 a | 24.1 | 36.5 |

| A1TP3r | 1.81 ± 0.01 a | 0.67 ± 0.05 a | 2.7 | 0.02 ± 0.01 a | 16.7 a | 24.1 | 44.3 |

| A1SP2r | 0.72 ± 0.05 a | 0.22 ± 0.09 a | 3.3 | 0.23 ± 0.00 b | 6.7 b | 15.0 | 59.8 |

| A2SP1r | 0.54 ± 0.01 a | 0.23 ± 0.07 a | 2.4 | 0.01 ± 0.01 a | 10.0 a | 18.4 | 14.1 |

| A2SP2r | 3.78 ± 0.07 b | 1.33 ± 0.11 b | 2.8 | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 50.0 c | 45.0 | 14.2 |

| A2SP5r (†) | 1.44 ± 0.02 a | 0.52 ± 0.00 a | 2.8 | 0.02 ± 0.02 a | 20.0 a | 26.6 | 230.0 |

| A2SP7r | 1.30 ± 0.07 a | 0.37 ± 0.09 a | 3.5 | 0.02 ± 0.03 a | 16.7 a | 24.1 | 52.1 |

| A2TP3r (†) | 2.85 ± 0.05 a | 0.80 ± 0.01 a | 3.6 | 0.02 ± 0.05 a | 26.7 a | 31.1 | 40.2 |

| A2TP5r | 2.74 ± 0.03 a | 0.10 ± 0.09 a | 27.4 | 0.05 ± 0.06 a | 10.0 a | 18.4 | 113.5 |

| A3TP1r | 1.59 ± 0.09 a | 0.42 ± 0.04 a | 3.8 | 0.02 ± 0.01 a | 3.3 b | 10.5 | 52.3 |

| A2NA3-1e | 1.38 ± 0.08 a | 0.35 ± 0.06 a | 3.9 | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | 16.7 a | 24.1 | 21.1 |

| A2NA3-2e | 0.65 ± 0.05 a | 0.22 ± 0.07 a | 3.0 | 0.01 ± 0.01 a | 16.7 a | 24.1 | 41.7 |

| A2YEMA2-1e | 0.71 ± 0.02 a | 0.15 ± 0.08 a | 4.7 | 0.01 ± 0.02 a | 10.0 a | 18.4 | 21.0 |

| A2YEMA6-1r | 1.40 ± 0.08 a | 0.65 ± 0.05 a | 2.2 | 0.02 ± 0.05 a | 16.7 a | 24.1 | 15.8 |

| A2YEMA8-1e | 0.63 ± 0.09 a | 0.17 ± 0.07 a | 3.7 | 0.01 ± 0.08 a | 10.0 a | 18.4 | 49.4 |

| A2YEMA8-2e | 0.77 ± 0.09 a | 0.38 ± 0.08 a | 2.0 | 0.01 ± 0.07 a | 13.3 a | 21.4 | 14.7 |

Pot culture experiment

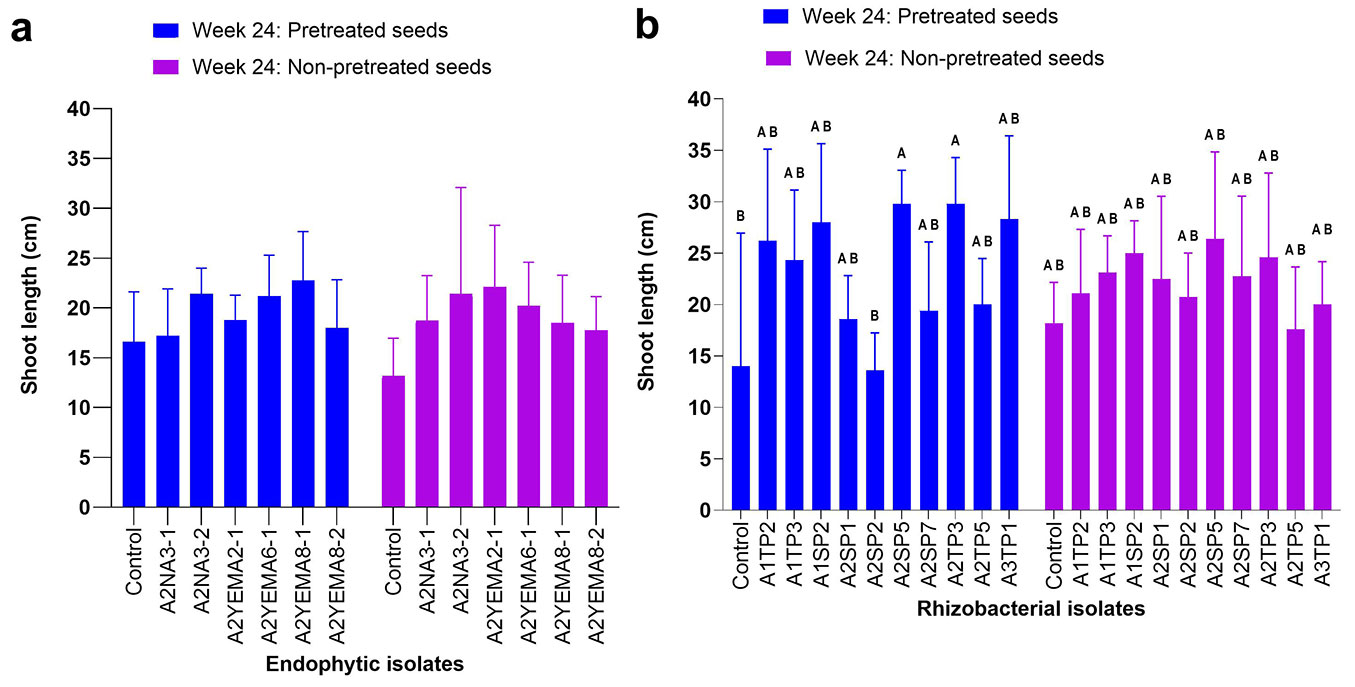

In pot experiments, statistical analysis revealed that inoculation with the native bacteria significantly influenced certain morphological parameters of A. confusa seedlings. Inoculation with endophytic strains did not significantly affect shoot length (two-way ANOVA, endophytic isolates, p = 0.086 - Fig. 1a). In contrast, inoculation with rhizospheric strains resulted in significant differences in shoot length (two-way ANOVA, rhizobacterial isolates, p = 0.001 - Fig. 1b), with some isolates (A2SP5 and A2TP3) promoting longer shoots compared to the control (Fig. 1b, Fig. S2 in Supplemenraty material). Seed pretreatment did not significantly affect shoot length in plants treated with endophytes (two-way ANOVA, seed pretreatment, p = 0.652 - Fig. 1a). Additionally, there was no significant interaction between endophytic bacterial inoculation and seed pretreatment (two-way ANOVA, bacterial inoculation × seed pretreatment, p = 0.729 - Fig. 1a). Similarly, for rhizobacterial isolates, seed pretreatment had no statistical effect on shoot length (two-way ANOVA, seed pretreatment, p = 0.489 - Fig. 1b), and no significant interaction was observed between bacterial inoculation and seed pretreatment (two-way ANOVA, bacterial inoculation × seed pretreatment, p = 0.286 - Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1 - Effect of endophytic and rhizospheric bacterial inoculation on A. confusa shoot growth in pots at week 24. Data are presented as means, with bars denoting the standard error, based on 10 seedlings per isolate. (a) Endophytic bacterial inoculation; (b) rhizospheric bacterial inoculation. Across bars, means without a common uppercase letter differ significantly (p < 0.05) after Tukey’s HSD test.

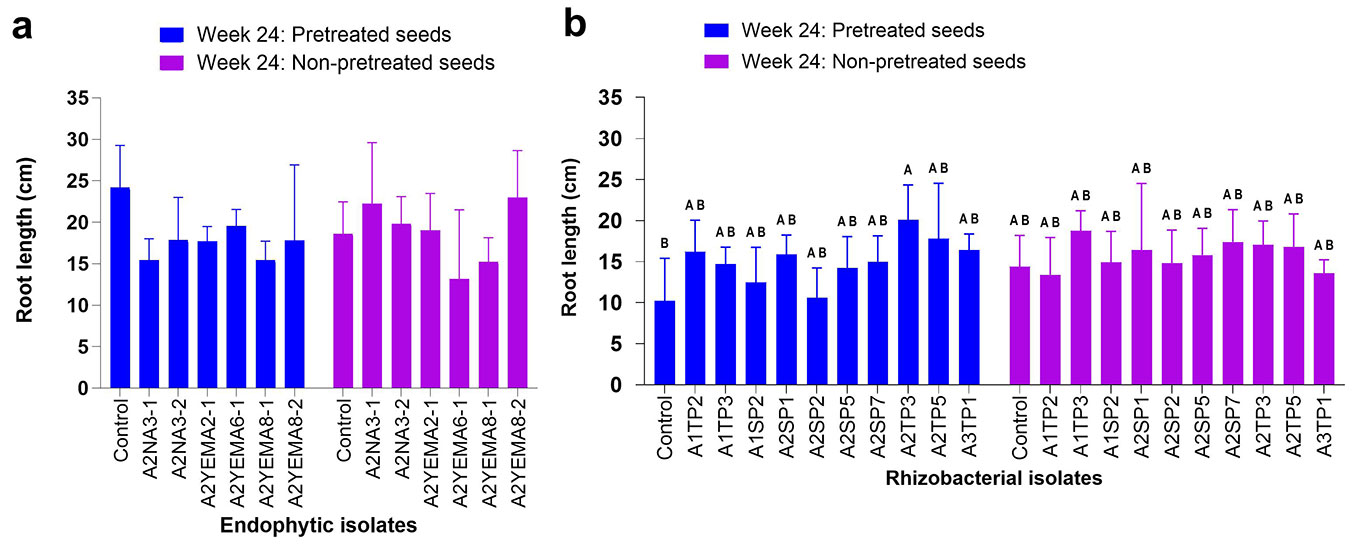

Inoculation with endophytic strains did not significantly affect root length (two-way ANOVA, endophytic isolates, p = 0.130 - Fig. 2a). Seed pretreatment also had no statistical effect (two-way ANOVA, seed pretreatment, p = 0.720), but there was a significant interaction between bacterial inoculation and seed pretreatment (two-way ANOVA, bacterial inoculation × seed pretreatment, p = 0.039). For rhizospheric bacterial inoculation, a statistically significant effect on root length (two-way ANOVA, rhizobacterial isolates, p = 0.023 - Fig. 2b). However, seed pretreatment had no significant effect (two-way ANOVA, seed pretreatment, p = 0.259 - Fig. 2b). In contrast, no significant interaction was observed between bacterial inoculation and seed pretreatment (two-way ANOVA, bacterial inoculation × seed pretreatment, p = 0.265 - Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2 - Effect of endophytic and rhizospheric bacterial inoculation on A. confusa root growth in pots at week 24. Data are presented as means, with bars denoting the standard error, based on 10 seedlings per isolate. (a) Endophytic bacterial inoculation; (b) rhizospheric bacterial inoculation. Across bars, means without a common uppercase letter differ significantly (p < 0.05) after Tukey’s HSD test.

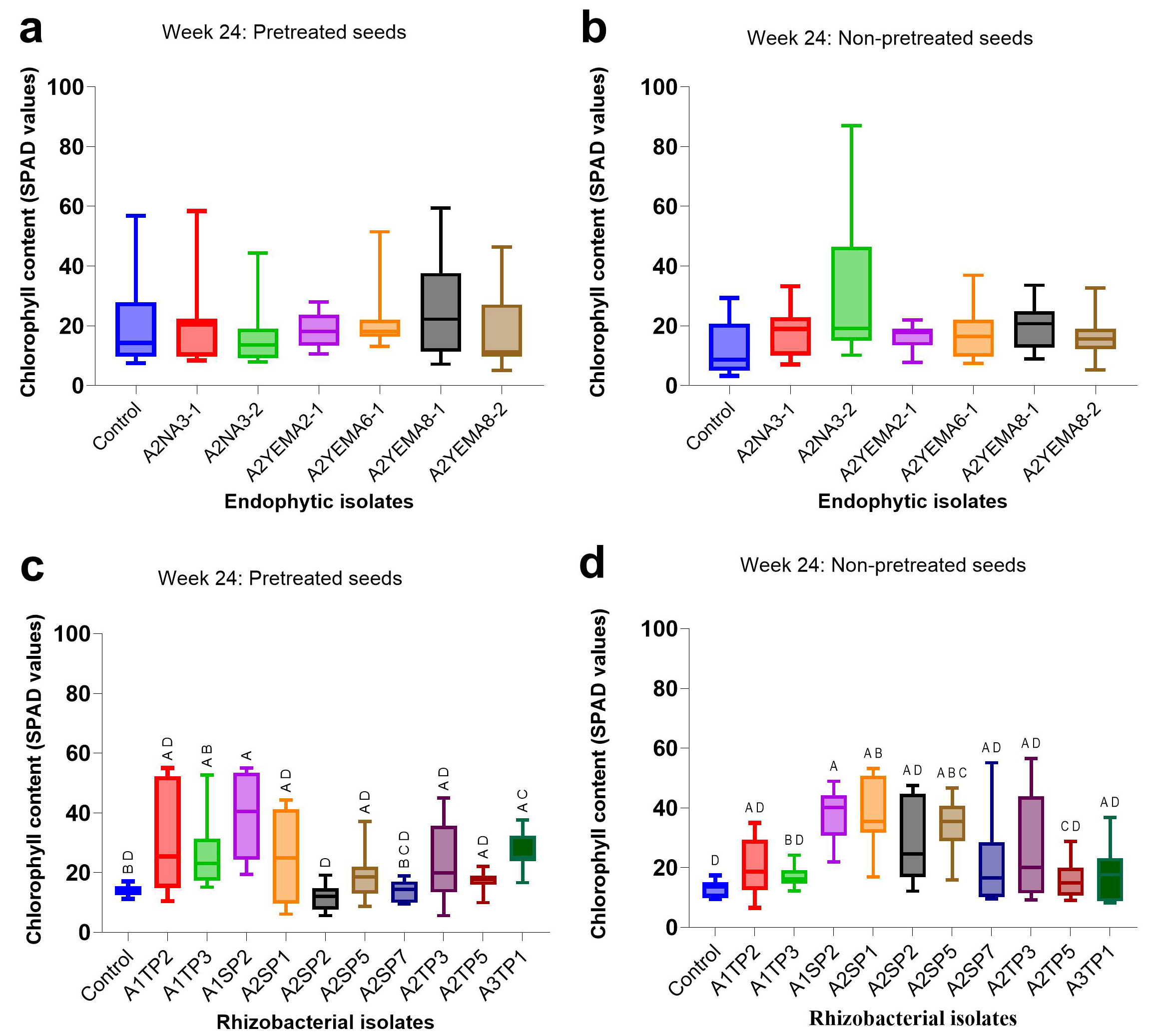

Chlorophyll content was not significantly affected by inoculation with endophytic bacterial strains in pretreated seeds (Kruskal-Wallis test: H = 6.302, df = 7, p = 0.390 - Fig. 3a) or non-pretreated seeds (Kruskal-Wallis test: H = 9.245, df = 7, p = 0.160 - Fig. 3b). However, rhizospheric bacterial inoculation had a statistically significant effect on chlorophyll content in both pretreated seeds (Kruskal-Wallis test: H = 45.70, df = 11, p < 0.001 - Fig. 3c) and non-pretreated seeds (Kruskal-Wallis test: H = 44.38, df = 11, p < 0.001 - Fig. 3d), particularly with isolate A1SP2 (Bacillus siamensis) and A3TP1 (Lelliottia jeotgali) in pretreated seeds, and isolate A1SP2 (Bacillus siamensis) and A2SP5 (Lysinibacillus sphaericus) in non-pretreated seeds.

Fig. 3 - Effect of endophytic and rhizospheric bacterial inoculation on chlorophyll content at week 24. Boxplots display the median and interquartile range (IQR) of chlorophyll content in 10 seedlings per bacterial isolate. Dunn’s post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction indicated that median values without a common uppercase letter differ significantly (p < 0.05). (a, b): Endophytic bacterial inoculation. (c, d): rhizospheric bacterial inoculation; (a, c): pretreated seeds; (b, d): non-pretreated seeds.

A two-way ANOVA (p < 0.05) was used to compare chlorophyll content between weeks 8 and 24 for each treatment. The chlorophyll SPAD values declined significantly with plant age in some treatments with endophytic bacterial inoculation (Fig. S3a, Fig. S3b - Supplementary material) and rhizospheric bacterial inoculation (Fig.S4a, Fig.S4b).

The overall survival percentage did not differ significantly between inoculated and uninoculated seedlings by the end of the experiment (two-way ANOVA, endophytic isolates: p = 0.340 - Fig. S5a; two-way ANOVA, rhizobacterial isolates, p = 0.417 -Fig.S5b). Control seedlings maintained a 100% average survival rate, while inoculated seedlings had an average survival rate of 80% (Fig. S5a, Fig.S5b). Seed pretreatment had no significant effect on survival percentage (two-way ANOVA, seed pretreatment, p = 0.088 - Fig. S5a; two-way ANOVA, seed pretreatment, p = 0.183 - Fig. S5b), and no significant interaction was observed between bacterial inoculation and seed pretreatment (two-way ANOVA, endophytic inoculation × seed pretreatment, p = 0.677 - Fig. S5b in Supplementary material; rhizobacterial inoculation × seed pretreatment, p = 0.899).

Seed pellet experiment

Among the tested seed pellet substrate mixtures, clay exhibited the highest water-holding capacity at 389‰, followed by organic material at 381‰, biochar at 349‰ and 312‰, and sawdust at 299‰ (one-way ANOVA, water holding capacity, p = 0.03 - Tab. 4). All bulking materials had a near-neutral pH range of 6.3 to 7.8, ideal for bacterial growth, with biochar pyrolyzed at 600 °C showing a significantly higher pH than other seed pellet components (one-way ANOVA, pH: p = 0.02, EC: p = 0.001 - Tab. 4).

Tab. 4 - Chemical properties of the seed pellet components used in this study. Data represent mean ± SD. Means labelled with different letters within a column significantly (p < 0.05) differ after Tukey’s HSD test. (1) Biochar obtained at of 300 °C. (2) Biochar obtained at 600 °C. Treatment (T1), clay:organic material (1:1); Treatment 2 (T2), clay:organic material (1:1) and added 1% biochar (pyrolysis at 600 °C); Treatment (T3), clay:organic material (1:1) and added 1% biochar (pyrolysis at 300 °C); Treatment (T4), clay (1:1) and added 10% sawdust.

| Component | pH (1:2 H2O) |

EC (1:2 H2O) (µS cm-1) |

Water holding capacity (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic material | 6.5 ± 0.1 a | 361 ± 5.1 c | 381 ± 0.0 a |

| Biochar1 | 7.2 ± 0.1 ab | 673 ± 1.4 b | 312 ± 0.1 ab |

| Biochar2 | 7.8 ± 0.5 b | 303 ± 1.9 c | 349 ± 0.0 ab |

| Sawdust | 6.9 ± 0.1 ab | 56 ± 0.1 d | 299 ± 0.1 b |

| Clay | 6.3 ± 0.6 a | 421 ± 1.5 b | 389 ± 0.0 a |

| Adhesive | 6.3 ± 0.3 a | 396 ± 0.8 bc | - |

| Treatment 1 (T1) | 6.8 ± 0.2 ab | 180 ± 0.6 d | - |

| Treatment 2 (T2) | 7.1 ± 0.3 ab | 520 ± 0.8 b | - |

| Treatment 3 (T3) | 7.3 ± 0.3 ab | 940 ± 1.0 a | - |

| Treatment 4 (T4) | 6.7 ± 0.1 ab | 440 ± 1.1 b | - |

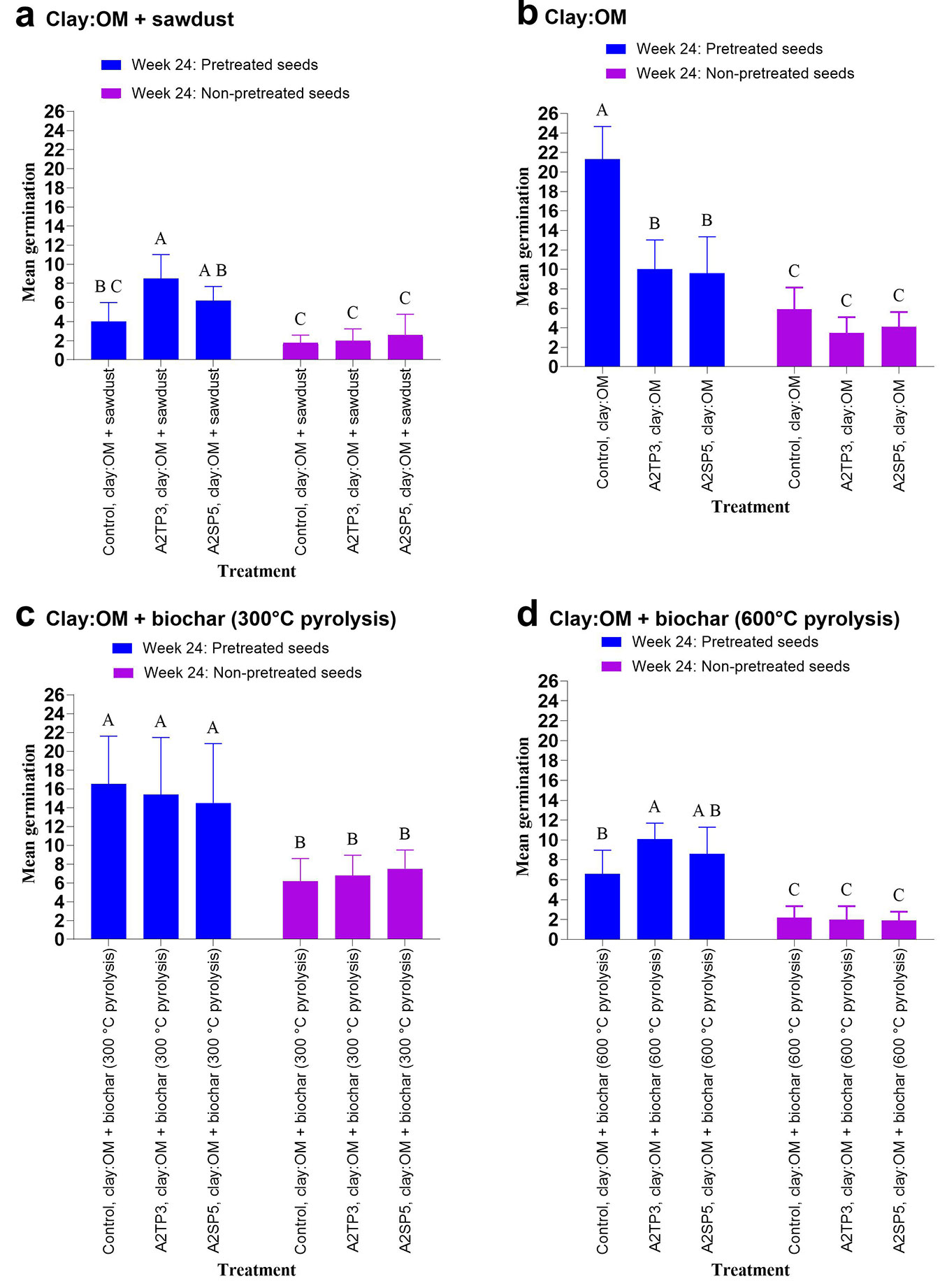

Two bacterial strains (A2TP3 and A2SP5) used for inoculation in the seed pellet experiment were selected for their positive performance in more than two PGP traits, with the A2TP3 isolate exhibiting a nitrogen-fixing ability (Tab. 1). Additionally, both isolates significantly promoted seedling growth (shoot length) in the pot experiment in the 24th week (Fig. 1b). Our analysis revealed that seed pretreatment had the most significant impact on plant responses across all substrates, consistently explaining the highest variation (from 47.49% to 72.39%) and demonstrating a highly significant effect (two-way ANOVA, seed pretreatment, p < 0.001 - Fig. 4a-d). Bacterial inoculation with the two strains A2TP3 (Bacillus proteolyticus) and A2SP5 (Lysinibacillussphaericus), had some impacts on germination in some substrates, such as clay (clay with sawdust, two-way ANOVA, p = 0.001 - Fig. 4a; clay with organic matter, two-way ANOVA, p < 0.01 - Fig. 4b) and biochar at 600 °C pyrolysis (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.019 - Fig. 4d), but had no significant effect on biochar produced at 300 °C pyrolysis (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.969 - Fig. 4c). Interestingly, the interaction between bacterial inoculation and seed pretreatment was also significant in clay (clay with sawdust, two-way ANOVA, p < 0.001 - Fig. 4a; clay with organic matter, two-way ANOVA, p = 0.001 - Fig. 4b) and biochar at 600°C pyrolysis (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.007 - Fig. 4d), implying that the bacteria’s effectiveness depended on whether the seeds were pretreated. However, this interaction was not observed in biochar at 300 °C (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.532 - Fig. 4c), where bacteria and their combination with seed pretreatment had no significant effect.

Fig. 4 - Effect of bacterial inoculation on A. confusa seed germination in seed pellets at day 15. Data represent means ± standard error of 20 pellets per treatment. Bars not sharing a common uppercase letter differ significantly after Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05). (a) Seed germination after bacterial inoculation; (b) Seed germination in bacterial inoculation in seed pellets. (c) Seed germination using pellets composed of a biochar (300 °C pyrolysis):organic matter (OM) substrate; (d) seed germination using pellets consisting of a biochar (600 °C pyrolysis):organic matter (OM) substrate. (OM): organic matter;

Discussion

Native bacterial isolation PGP traits

Isolating native strains was essential for selecting those with plant growth-promoting (PGP) traits. Applying bacteria with PGP traits in landslide areas holds substantial promise, as reforestation in these regions is challenging due to poor soil fertility and the loss of beneficial plant-associated microorganisms ([37]). This study identified several potential strains for promoting the growth of A. confusa.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis revealed that more than half of the isolates belonged to the well-studied genus Bacillus, including Bacillus proteolyticus, Bacillus siamensis, Bacillus megaterium, and Bacillus tequilensis (Tab. 1). The dominance of Bacillus in A. confusa plantations may be attributed to its resilience in adverse environmental conditions and its remarkable capacity for rapid replication ([45]). However, the use of Bacillus species in landslide reforestation remains limited.

The other isolates identified in this study belonged to Brevibacillus sp. and Lysinibacillus sp. Pseudomonas sp., Curtobacterium sp., Arthrobacter sp., and Lelliottia sp., whose effects on plant growth have not been extensively studied. Previous research has indicated that Pseudomonas sp. also possess plant growth-promoting traits and exhibit biocontrol effects through induced systemic resistance (ISR - [54]), likely due to their chitinase activity ([8]). Additionally, Bacillus megaterium and Lysinibacillus sp. have been reported to be effective phosphorus solubilizers when inoculated into wheat and banana, respectively ([12], [3]). We also found that isolate A2SP1 exhibited phosphorus-solubilizing activity (Tab. 1).

Further, the genus Arthrobacter has been shown to alleviate soil salinity and phosphorus deficiency ([21]). Co-inoculation with Arthrobacter sp. and Bacillus sp. has been shown to promote the growth of maize (Zea mays) and groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) in saline and phosphorus-deficient soils ([23], [53]). Similarly, Curtobacterium sp. is salt-tolerant, alleviating salt stress in paddy fields by reducing Na+ uptake and maintaining K+/Na+ balance ([52], [34]). Further studies could explore the potential of combining bacteria with complementary functions.

Effect of native bacterial inoculation on A. confusa germination and growth

In the Petri dish experiment, the response of A. confusa seeds to inoculation varied significantly among isolates (Tab. 2, Tab. 3). However, none of the isolates in this study exhibited very high IAA levels (Tab. 1). Previous research suggests that excessive IAA can inhibit seedling growth. For example, Park et al. ([39]) demonstrated that Enterobacter sp. I-3, a high IAA-producing strain, suppressed radish seedling development. Similarly, E. taylorae was shown to suppress weed growth due to its high IAA production ([44]).

In the pot experiment, some isolates significantly enhanced growth parameters of A. confusa seedlings, including shoot length (Fig. 1) and leaf chlorophyll content (Fig. 3c, Fig. 3d). The considerably longer shoots observed in some inoculated seedlings in this study represent a critical growth trait in degraded landslide areas, as taller plants can compete for light with surrounding grasses and plants ([35]). Similar studies on other Acacia species, such as Acacia ariculiformis and Acacia cyanophylla, have also reported improved growth performance following rhizobacterial inoculation ([27]). These effects may be attributed to plant growth-promoting (PGP) traits, including siderophore production, phosphate solubilization, IAA synthesis, and ethylene suppression in roots ([17], [22], [5]).

Our study showed that bacterial inoculation had no significant effect on root length in the pot experiments (Fig. 2a), except for strain A2TP3, Bacillus proteolyticus, which significantly improved root length in pretreated seeds (Fig. 2b). This agrees with other studies showing that inoculation of A. confusa with bacterial strains such as Bradyrhizobium alkanii can positively affect root growth ([29]).

In this study, endophytic bacterial inoculation did not significantly affect chlorophyll content compared to the control (Fig. 3a, Fig. 3b). However, rhizospheric bacterial inoculation, such as with A1SP2 (Bacillus siamensis), resulted in a significant increase in chlorophyll content (Fig. 3c, Fig. 3d). Similarly, previous studies have reported increased chlorophyll content following bacterial inoculation in other plant species, including conifers ([14]). Surprisingly, a two-way ANOVA (p < 0.05) revealed a significant decline in chlorophyll SPAD values with plant age for some bacterial isolates (Fig. S3, Fig. S4 - Supplementary material). These findings contrast with those of Martin-Laurent et al. ([31]), who reported that inoculation of A. mangium with Bradyrhizobium strains significantly increased chlorophyll content. This decline in SPAD values in the present study may be attributed to the rising monthly average temperatures from planting to harvest. Additionally, the observed decrease may indicate nitrogen and other mineral deficiencies, likely due to the small pots, which limited soil volume and nutrient availability, as no commercial fertilizer was added to the substrate.

Germination rates varied across seed pellet mixtures (Fig. 4), likely due to the physical and physicochemical properties of the bulking materials and adhesive used during pelleting ([24], [42]). Some studies have also shown that seed pellets can enhance seed growth ([18]). Surprisingly, inoculation with the two strains, A2TP3 (Bacillus proteolyticus) and A2SP5 (Lysinibacillus sphaericus), significantly inhibited the germination of A. confusa seeds in the clay:OM substrate (Fig. 4b). This inhibition may be attributed to competition for oxygen and moisture between the seeds and bacterial inoculum within the pellets. Similar findings were reported for barley, in which Azotobacter sp. competed with the seed embryo for oxygen, thereby preventing germination ([20]). On the other hand, the strain A2TP3 significantly improved germination in the other substrates (Fig. 4a, Fig. 4d), except in the clay:OM + biochar (300 °C pyrolysis) substrate (Fig. 4c). This suggests its potential for use in seed pelleting.

Notably, seed pretreatment had a significant effect on germination across all substrates (Fig. 4a-d). This can be attributed to hot water treatment, which promotes germination in dormant, hard-coated seeds by leaching chemical inhibitors, softening the seed coat, and increasing water and oxygen permeability ([33]).

Conclusions

This study identified 16 bacterial strains that significantly affected seed germination in Petri dishes and subsequently tested them in the pot experiment. The pot experiment demonstrated a positive effect of bacterial inoculation on the phenotypic traits of A. confusa seedlings, suggesting that these indigenous bacterial strains have the potential for use in field trials to support the restoration of landslide areas. However, seeds inoculation with the bacterial isolates A2TP3 (Bacillus proteolyticus) and A2SP5 (Lysinibacillus sphaericus) inhibited A. confusa seed germination in the clay:OM substrate during seed pelleting. Future studies should investigate the physical properties of seed pellets, including friability, dissolution, and hardness, to identify the optimal mixture for pelleting A. confusa seeds.

Acknowledgements

PNN, WCC, GZMS, and KJC conceived the study. PNN and KCH performed the experiments with the inputs from WCC, GZMS, and KJC. PNN conducted data analysis using inputs from WCC, GZMS, and KJC. PNN wrote the manuscript with the inputs from WCC, KCH, GZMS, and KJC. All authors commented and approved the final version of the manuscript. We sincerely appreciate the important assistance and support from Miss Jean Chang, Dr. Fong-Tin Shen, and Dr. Shih-Hao Jien. This study was supported by the International Cooperation Development Fund (ICDF) in Taiwan.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Department of Life Sciences, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 70101 (Taiwan)

International Bachelor Program in Agribusiness, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, 40227 (Taiwan)

Guo-Zhang Michael Song 0000-0002-9266-3690

Department of Soil and Water Conservation, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung 40227 (Taiwan)

International Master Program in Agriculture, Innovation and Development Center of Sustainable Agriculture, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung City, 402 (Taiwan)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Nxumalo PN, Chen W-C, Hsu K-C, Song G-ZM, Chao K-J (2026). Maximizing growth of Acacia confusa through native plant growth-promoting bacterial inoculation and seed pelleting for revegetation in landslide areas. iForest 19: 28-37. - doi: 10.3832/ifor4082-018

Academic Editor

Maurizio Ventura

Paper history

Received: Feb 21, 2022

Accepted: Jul 14, 2025

First online: Jan 11, 2026

Publication Date: Feb 28, 2026

Publication Time: 6.03 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2026

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 1251

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 508

Abstract Page Views: 356

PDF Downloads: 356

Citation/Reference Downloads: 0

XML Downloads: 31

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 47

Overall contacts: 1251

Avg. contacts per week: 186.32

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

(No citations were found up to date. Please come back later)

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Use of overburden waste for London plane (Platanus × acerifolia) growth: the role of plant growth promoting microbial consortia

vol. 10, pp. 692-699 (online: 17 July 2017)

Research Articles

Response of soil bacterial communities to nitrogen and phosphorus additions in an age-sequence of subtropical forests

vol. 14, pp. 71-79 (online: 11 February 2021)

Research Articles

Variations in the performance of hybrid poplars subjected to the inoculation of a microbial consortium and water restriction

vol. 16, pp. 352-360 (online: 13 December 2023)

Research Articles

Moderate wildfire severity favors seed removal by granivores in a Mexican pine forest

vol. 18, pp. 121-127 (online: 24 May 2025)

Research Articles

Fungal and bacterial communities in a forest relict of Pinus pseudostrobus var. coatepecensis

vol. 16, pp. 299-306 (online: 09 November 2023)

Research Articles

The effect of seed size on seed fate in a subtropical forest, southwest of China

vol. 9, pp. 652-657 (online: 04 April 2016)

Research Articles

Effects of substrate and ectomycorrhizal inoculation on the development of two-years-old container-grown Norway spruce (Picea abies Karst.) seedlings

vol. 8, pp. 487-496 (online: 10 November 2014)

Research Articles

Seed trait and rodent species determine seed dispersal and predation: evidences from semi-natural enclosures

vol. 8, pp. 207-213 (online: 28 August 2014)

Research Articles

The combined effects of Pseudomonas fluorescens CECT 844 and the black truffle co-inoculation on Pinus nigra seedlings

vol. 8, pp. 624-630 (online: 08 January 2015)

Research Articles

Fertilisation of Quercus seedlings inoculated with Tuber melanosporum: effects on growth and mycorrhization of two host species and two inoculation methods

vol. 10, pp. 267-272 (online: 13 December 2016)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword