Abundance and impact of egg parasitoids on the pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa) in Bulgaria

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 14, Issue 5, Pages 456-464 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor3538-014

Published: Oct 02, 2021 - Copyright © 2021 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

We collected 2297 egg batches of the pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa) during the period 1991-2018 from 44 sites in Bulgaria. The sampling sites were classified into three groups according to T. pityocampa phenological form (early, late and both forms) as well as in two groups of its range (historical and newly colonized areas). Seven primary egg parasitoids were identified: Ooencyrtus pityocampae, Baryscapus servadeii, Pediobius bruchicida, Anastatus bifasciatus, Eupelmus (Macroneura) vesicularis, Eupelmus (Macroneura) vladimiri and Trichogramma sp., and one hyperparasitoid, Baryscapus transversalis. The average impact of egg parasitoids (the percentage of parasitized host eggs) on T. pityocampa in Bulgaria was 13.8%. The two main parasitoids, O. pityocampae and B. servadeii, parasitized about 90% of the host eggs. The remaining parasitoids were of insignificant consequence to the parasitism of the T. pityocampa eggs, but in areas recently colonized by the pest, A. bifasciatus and Trichogramma sp. had a noticeable share (up to 33% of the impact). In old habitats of the host (areas colonized more than 10 years), the impact was almost two times higher than in new ones (15.3% vs. 8.6%). This could be attributed to B. servadeii, which was rare in newly colonized areas of T. pityocampa (impact 0.5%), but strongly dominant in old habitats (impact 7.2%). In contrast, O. pityocampae had a significant impact in new habitats (4.9%), which increased only slightly over time, reaching 6.0% in old habitats. There was no significant difference between the percentage of parasitism of the early and late form of the pine processionary moth (14.8% vs. 15.9%). However, there was a significant difference in the share of separate species in the parasitoid complex: in the early form, B. servadeii definitely dominated (63% of the infested eggs), while in the late form O. pityocampae dominated, although not so strongly (52% of the infested eggs). This difference is most likely due to the phenological characteristics of the parasitoids and the two forms of T. pityocampa. B. transversalis secondarily infested about 5% of the eggs of O. pityocampae and B. servadeii. This percentage was slightly lower for new habitats and habitats of the early form of pine processionary moth (3% and 4%, respectively). The impacts of the main parasitoids O. pityocampae and B. servadeii as well as the total impact of the parasitoid complex as a whole decreased with altitude. Conversely, the impacts of A. bifasciatus and Trichogramma sp. slightly increased with altitude probably due to the reduced competition of the main parasitoids.

Keywords

Thaumetopoea pityocampa, Distribution, Habitats, Expansion, Phenological Forms, Egg Parasitism, Bulgaria

Introduction

The pine processionary moth, Thaumetopoea pityocampa Denis & Schiffermüller, 1775 (Lepidoptera: Notodontidae) is among the most dangerous insect pests in pine forests. The northern border of its distribution passes through Bulgaria where two phenological forms of the species are widespread: the summer (early developing) and the winter (late developing - [40], [23]). The abundance of T. pityocampa has been highly influenced by human activities. Since 1978, the annual size of its attacks in Bulgaria has increased five times as a consequence of the large-scale afforestation with black pine (Pinus nigra Arn.) and Scots pine (P. sylvestris L.) in the period 1950-1980 ([20]). Until the 1990s, the pest attacks remained limited to its historical range, where it has been known since the 1910s - southwestern and south central Bulgaria, both traditionally assigned to the Continental-Mediterranean and the European-Continental climatic zones ([28]). In 1991, economically significant attacks began in Central Bulgaria, northeast of the historical range. As a result, a stable expansion zone of T. pityocampa developed in Central Bulgaria, despite all control measures ([22]). The front of expansion is steadily moving east at a speed of about 2.5 km per year on the southern slope of the Balkan Range and in Sredna Gora Mt. Currently, the expansion zone coincides with Stara Zagora region ([42]).

The egg parasitoids are the most significant biological factor regulating the numbers of the pine processionary moth ([19], [31], [39]). According to Masutti ([16]), temperature is the major factor determining the favorable ecological niche of the main primary egg parasitoids - Ooencyrtus pityocampae Mercet (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) and Baryscapus servadeii Domenichini (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae). In addition to temperature, a number of other biotic and abiotic factors are known to affect the impact of primary egg parasitoids: the hyperparasitoid Baryscapus transversalis Graham (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae - [4], [5], [19]), the vegetation diversity near the studied sites ([19]), etc. Long-term studies have shown that adaptation time (i.e., the time after colonization of the area by the pine processionary moth) is also important for the development of host-specific parasitoids ([21]).

The present work summarizes the case studies on T. pityocampa egg parasitoids made in Bulgaria. It is focused on the relative share and abundance of different species in the parasitoid complex, their impact on the pest and the peculiarities of the parasitism in new and old habitats, as well as on the two different phenological forms.

Material and methods

The present work summarizes case studies made during 1991-2018 in 44 sites all over the range of the pine processionary moth in Bulgaria (Tab. 1, Fig. 1). The studied sites are located in an area of approximately 20.000 km2. The distance between the southernmost site (Dzherovo) and the northernmost one (Klisura) is about 160 km, and between the westernmost and easternmost sites (Kyustendil and Maglizh, respectively) is 240 km.

Tab. 1 - Characteristics of the studied localities of T. pityocampa and sampled biological material. (OH): old habitats; (NCA): newly colonized areas (new habitats).

| Habitat | N | Locality, District | Altitude (m a.s.l.) |

No. sampling years | T. pityocampa range |

Sampling (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Year of collection | Egg batches | Eggs | |||||

| Early phenological form | 1 | Dobrostan, Plovdiv | 850 | 1 | 2018 | NCA | 8 | 1740 |

| 2 | Dyulitsa, Kardzhali | 390 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 7 | 1815 | |

| 3 | Domishte, Kardzhali | 420 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 30 | 7164 | |

| 4 | Drangovo, Kardzhali | 440 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 6 | 1348 | |

| 5 | Dzherovo, Kardzhali | 460 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 20 | 4535 | |

| 6 | Fotinovo, Kardzhali | 450 | 1 | 2018 | OH | 180 | 38202 | |

| 7 | Kandilka, Kardzhali | 450 | 1 | 2018 | OH | 17 | 3780 | |

| 8 | Kardzhali, Kardzhali | 400 | 1 | 1995 | OH | 67 | 13560 | |

| 9 | Kayaloba, Kardzhali | 490 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 18 | 3337 | |

| 10 | Medevtsi, Kardzhali | 470 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 30 | 6832 | |

| 11 | Yanino, Kardzhali | 410 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 26 | 5428 | |

| 12 | Hvoina, Smolyan | 950 | 1 | 1995 | NCA | 14 | 2350 | |

| Late phenological form | 13 | Asenovgrad, Plovdiv | 400 | 2 | 2016, 2017 | OH | 41 | 9455 |

| 14 | Banya, Plovdiv | 340 | 4 | 1992, 1993, 1996, 1999 | OH | 93 | 20565 | |

| 15 | Garmen, Blagoevgrad | 700 | 2 | 2016, 2017 | OH | 42 | 8839 | |

| 16 | Gega, Blagoevgrad | 856 | 2 | 2017 | OH | 38 | 8226 | |

| 17 | Gotse Delchev, Blagoevgrad | 830 | 2 | 2016, 2017 | OH | 51 | 11935 | |

| 18 | Dikchan, Blagoevgrad | 900 | 3 | 2016, 2017, 2018 | OH | 107 | 24814 | |

| 19 | Dupnitsa, Blagoevgrad | 725 | 2 | 1994, 1995 | OH | 56 | 13732 | |

| 20 | Ivailovgrad, Haskovo | 285 | 5 | 2009-10, 2012, 2016, 2018 | OH | 145 | 39252 | |

| 21 | Marikostinovo, Blagoevgrad | 180 | 6 | 1991-1996 | OH | 329 | 76868 | |

| 22 | Parvomai, Blagoevgrad | 450 | 3 | 2016, 2017, 2018 | OH | 90 | 20978 | |

| 23 | Plosky, Blagoevgrad | 515 | 3 | 1991, 1992, 1994 | OH | 73 | 16211 | |

| 24 | Satovcha, Blagoevgrad | 950 | 4 | 1994, 2000, 2002, 2008 | OH | 74 | 15890 | |

| 25 | Sandanski, Blagoevgrad | 450 | 3 | 1994, 1997, 2017 | OH | 57 | 12792 | |

| 26 | Maglizh, Stara Zagora | 365 | 2 | 2016, 2017 | NCA | 25 | 6529 | |

| 27 | Klisura, Plovdiv | 710 | 3 | 2016, 2017, 2018 | OH | 96 | 22000 | |

| 28 | Kurtovo, Plovdiv | 500 | 3 | 1991, 1995, 1996 | OH | 41 | 8979 | |

| 29 | Kyustendil, Kyustendil | 1045 | 6 | 1994-95, 1997-99, 2014 | NCA | 96 | 14057 | |

| 30 | Rilski Ðœanastir, Kyustendil | 700 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 6 | 1478 | |

| 31 | Vetren, Kyustendil | 680 | 3 | 2013, 2014, 2016 | NCA | 85 | 20950 | |

| Common (both early and late phenological forms) |

32 | Hisaria, Plovdiv | 415 | 2 | 2016, 2018 | OH | 59 | 15009 |

| 33 | Karlovo, Plovdiv | 535 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 8 | 2183 | |

| 34 | Chirpan, Stara Zagora | 480 | 1 | 2017 | NCA | 13 | 2894 | |

| 35 | Kazanlak, Stara Zagora | 475 | 1 | 2016 | NCA | 71 | 18010 | |

| 36 | Dolno Sahrane, Stara Zagora | 450 | 2 | 2016, 2018 | OH | 40 | 9247 | |

| 37 | Sladak kladenets, Stara Zagora | 400 | 1 | 2016 | NCA | 36 | 8279 | |

| 38 | Lesichevo, Pazardzhik | 460 | 1 | 2016 | NCA | 11 | 2686 | |

| 39 | Panagyurishte, Pazardzhik | 650 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 5 | 1418 | |

| 40 | Peshtera, Pazardzhik | 640 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 10 | 2724 | |

| 41 | Rakitovo, Pazardzhik | 1000 | 1 | 2016 | OH | 5 | 1242 | |

| 42 | Momchilgrad, Kardzhali | 400 | 1 | 2018 | OH | 17 | 3639 | |

| 43 | Zelenikovo, Plovdiv | 425 | 1 | 2016 | NCA | 20 | 5331 | |

| 44 | Zhenda, Kardzhali | 400 | 2 | 2016, 2017 | OH | 34 | 8421 | |

| - | - | Total | - | 2297 | 509642 | |||

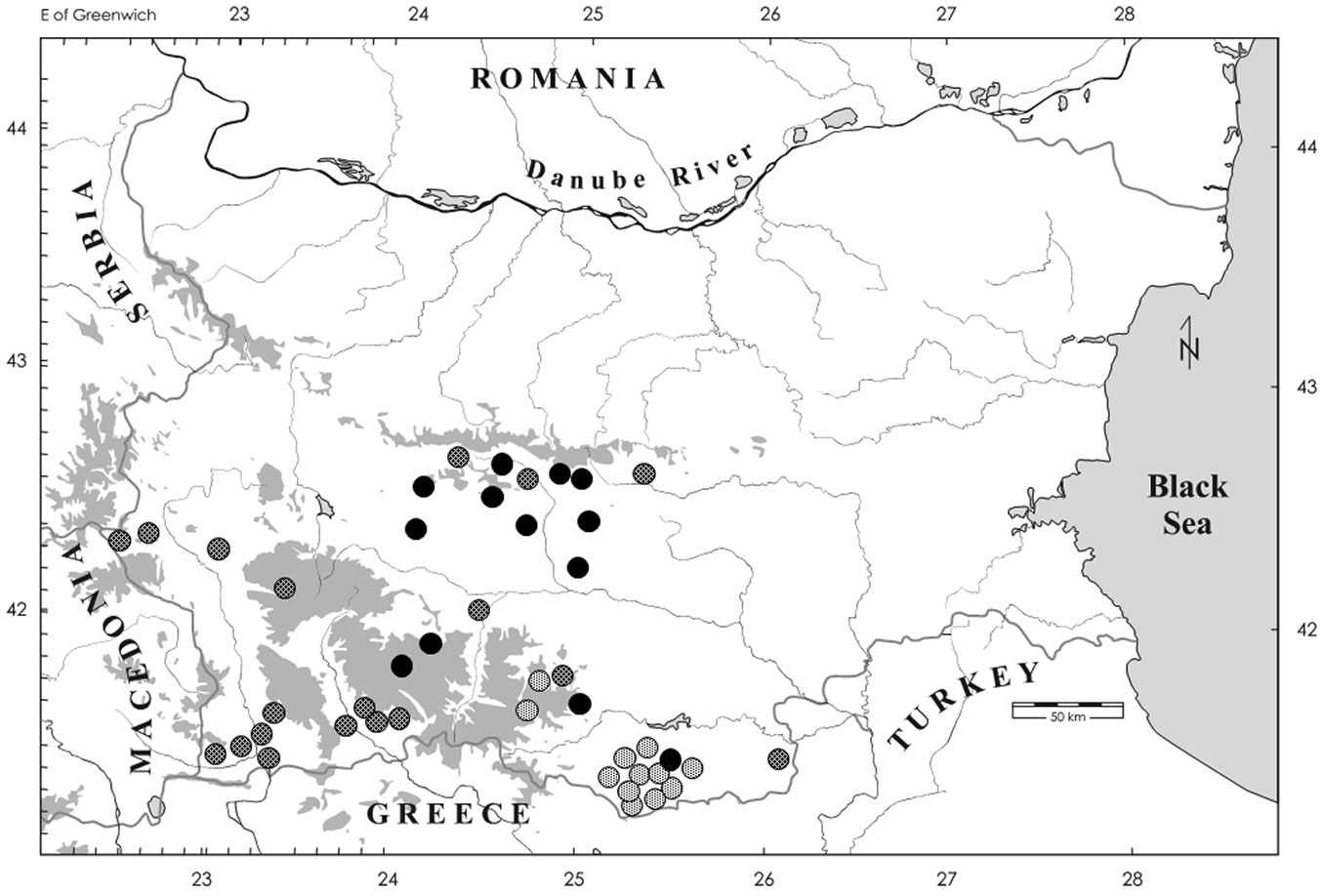

Fig. 1 - Studied habitats of Thaumetopoea pityocampa in Bulgaria. Early phenological form habitats are indicated by light grey dots, late phenological form habitats by dark grey dots, while black dots indicate both early and late phenological forms habitats.

The current range of the pine processionary moth in Bulgaria is outlined by the studied sites (Fig. 1). In the Sofia valley, the pine processionary moth occurs latently, in small numbers and without making attacks, due to the continental climate of the place. In the continental North of Bulgaria (i.e., the Danube plain, where pine plantations are rare) and on the northern slope of the Balkan Range, the pine processionary moth has not yet been reported. The pest is also absent to the east of the zone of expansion in South Bulgaria, including Burgas district on the Black Sea coast, strongly influenced by Mediterranean climate.

The biological material (2297 egg batches containing 524.724 eggs) included both single and multiple samples, with up to six generations of T. pityocampa (in Kyustendil and Marikostinovo). The egg batches collected at the individual sites ranged from 5 (Panagiurishte, Rakitovo) to 329 (Marikostinovo). The number of eggs in different sites varied from 1242 (Rakitovo) to 76.868 (Marikostinovo). Over the years, the material has been collected for different purposes. The predominant part of the studied biological material was collected in the historical range of T. pityocampa in Bulgaria. After the beginning of pest expansion, additional biological material was collected in the expansion zone. After establishing the early form, a number of studies were focused in these localities.

All sites were divided into three groups according to T. pityocampa phenological form: (i) early form habitats; (ii) late form habitats; (iii) both form habitats (i.e., where both early and late forms are present in the same area, sometimes on the same tree). In addition, in order to take into account the dynamics of the processes, the sampling sites were divided into: (i) old habitats (most of them), i.e., areas where T. pityocampa had been present for more than 10 years at the time of sampling; and (ii) new habitats, i.e., newly occupied areas where the pest had penetrated less than 10 years ago. For the same purpose, the sites were also divided into two other groups: (i) habitats from the historic range, where the pine processionary had been reported before 1991; and (ii) habitats from its expansion zone, which emerged in the Stara Zagora region in 1991 (Kazanlak, Sladak Kladenets, Chirpan, Dolno Sahrane, Maglizh). As the species has been expanding since the 1990s, it is important to note that there are new and old habitats in both the historic area and the area of expansion. The above subdivisions of the sampling sites were introduced to test for differences in the dynamics of the host and parasitoids in the different habitats.

Collected egg batches were transported to the laboratory of entomology at the Forest Research Institute in Sofia. The scales of the egg batches were removed, and the samples were analysed according to Tsankov et al. ([40]). The egg batches were placed individually in test tubes covered by cotton stoppers and kept at room temperatures (20-22 °C). The samples were checked periodically and the emerged parasitoids were separated and identified under a stereomicroscope (40×). At the end of the experiments (10-12 months after sampling), the eggs were dissected and analyzed in detail.

The parasitoids that had emerged before sample collection were determined by their meconia and remains, according to Schmidt & Kitt ([29]), Tanzen & Schmidt ([33]) and Tsankov et al. ([40]). The parasitoids emerged in the test tubes were identified by the following keys, according to the taxonomic group: Encyrtidae ([36], [38]); Eulophidae ([37], [10], [11]); Eupelmidae ([35], [8]); Trichogrammatidae ([25]). A part of the collected biological material was identified or confirmed by Dr. P. Boyadzhiev and Dr. M. Antov (Plovdiv University “P. Hilendarski”, Bulgaria) and Dr. E. Yegorenkova (Ulyanovsk State Pedagogical University, Russia).

In order to allow the comparison among different datasets, the average impact of the parasitoids (i.e., the rate of parasitism on T. pityocampa eggs) was chosen as the main indicator. In this way, the influence of different intensity of the research and the different number of repetitions in the different datasets is largely eliminated.

Statistical analysis was made using the package Statistica® v. 12.0 for Windows (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). To compare the means, the t-test for independent samples was applied, with normality control.

Results

Seven primary egg parasitoids of the pine processionary moth were established in Bulgaria: Ooencyrtus pityocampae Mercet, 1921 (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae); Baryscapus servadeii Domenichini, 1965; Pediobius bruchicida Rondani, 1872 (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae); Anastatus bifasciatus Fonscolombe, 1832; Eupelmus (Macroneura) vesicularis Retzius, 1783; Eupelmus (Macroneura) vladimiri Fusu, 2017 (Hymenoptera: Eupelmidae) and Trichogramma sp. (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae), and one hyperpasitoid, Baryscapus transversalis Graham, 1991.

The majority of the studied sites were dominated by O. pityocampae (19 sites, 43.2% - Tab. 2), followed by B. servadeii (17 sites). A. bifasciatus was the dominant species in six localities (Dyulitsa, Hvoina, Garmen, Chirpan, Rakitovo, Vetren), and Trichogramma sp. in two (Dobrostan, Asenovgrad).

Tab. 2 - Relative share and impact (in parentheses) of egg parasitoids of T. pityocampa in studied localities in Bulgaria. (Op): Ooencyrtus pityocampae; (Bs): Baryscapus servadeii; (Bt): Baryscapus transversalis; (Ab): Anastatus bifasciatus; (Tsp): Trichogramma sp.; (Pb): Pediobius bruchicida; (Ev1): Eupelmus vladimiri; (Ev2): Eupelmus vesicularis.

| Habitats | Locality | Total impact (%) |

Relative share (impact) of parasitoids (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Op | Bs | Bt | Ab | Tsp | Pb | Ev1 | Ev2 | |||

| Early phenological form | Dobrostan | 9.4 | 0.6 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.1) | - | 95.7 (8.9) | - | - | - |

| Dyulitsa | 10.2 | 19.6 (2.0) | - | - | 80.4 (8.2) | - | - | - | - | |

| Domishte | 18.2 | 16.2 (3.0) | 83.6 (15.2) | 0.2 (0.04) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Drangovo | 34.6 | 2.6 (0.9) | 97.4 (33.7) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Dzherovo | 7.1 | 6.2 (0.4) | 90.0 (6.4) | - | 3.8 (0.3) | - | - | - | - | |

| Fotinovo | 4.5 | 33.3 (1.5) | 41.4 (1.8) | 17.8 (0.8) | 0.4 (0.02) | 1.5 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.02) | 5.0 (0.3) | - | |

| Hvoina | 0.3 | - | - | - | 100.0 (0.3) | - | - | - | - | |

| Kandilka | 14.1 | 30.4 (4.3) | 52.1 (7.3) | 6.1 (0.9) | 9.2 (1.3) | 1.9 (0.3) | - | - | - | |

| Kardzhali | 25.7 | 4.9 (1.3) | 86.3 (22.2 | 2.6 (0.7) | 5.6 (1.4) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.02 (0.01) | - | - | |

| Kayaloba | 24.0 | 46.5 (11.2) | 47.3 (11.4) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.0 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.03) | - | - | - | |

| Medevtsi | 8.8 | 35.0 (3.1) | 45.5 (4.0) | 6.0 (0.5) | 13.4 (1.2) | - | - | - | 0.1 (0.03) | |

| Yanino | 20.4 | 47.7 (9.7) | 45.5 (9.3) | 5.1 (1.1) | 1.5 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.04) | - | - | - | |

| Late phenological form | Asenovgrad | 6.4 | 29.4 (1.9) | 14.3 (0.9) | 6.3 (0.4) | 13.8 (0.9) | 36.2 (2.3) | - | - | - |

| Banya | 20.2 | 74.5(15.1) | 19.4 (3.9) | 0.3 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.2) | 4.6 (0.9) | 0.1 (0.01) | - | - | |

| Dikchan | 14.6 | 24.8 (3.6) | 51.0 (7.5) | 10.2 (1.5) | 12.6 (1.8) | 1.4 (0.2) | - | - | - | |

| Dupnitsa | 11.4 | 78.2 (8.9) | 13.3 (1.5) | 3.6 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.1) | - | - | - | |

| Garmen | 13.0 | 31.9 (4.2) | 23.1 (3.0) | 8.5 (1.1) | 35.5 (4.6) | 1.0 (0.1) | - | - | - | |

| Gega | 11.5 | 13.3 (1.2) | 75.4 (8.9) | 5.5 (0.7) | 3.7 (0.4) | 2.1 (0.2) | - | - | - | |

| Gotse Delchev | 8.4 | 25.5 (2.1) | 30.4 (2.6) | 16.6 (1.4) | 24.4 (2.0) | 3.1 (0.3) | - | - | - | |

| Ivailovgrad | 18.2 | 27.7 (5.0) | 57.7 (10.5) | 5.2 (0.9) | 9.2 (1.7) | - | 0.2 (0.1) | - | - | |

| Kurtovo | 20.5 | 91.2 (18.7) | 2.8 (0.6) | 3.9 (0.8) | 0.2 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.4) | - | - | 0.1 (0.1) | |

| Klisura | 22.2 | 23.7 (5.3) | 66.4 (14.7) | 2.2 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.3) | 6.2 (1.4) | 0.1 (0.02) | - | - | |

| Maglizh | 13.6 | 88.2 (12.0) | 1.7 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.5) | 4.1 (0.6) | 2.0 (0.3) | - | - | - | |

| Marikostinovo | 23.3 | 91.4 (21.3) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.2) | 7.0 (1.6) | 0.1 (0.01) | 0.2 (0.05) | - | 0.1 (0.001) | |

| Kyustendil | 5.9 | 44.4 (2.6) | 12.5 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.01) | 6.8 (0.4) | 36.2 (2.2) | - | - | - | |

| Parvomay | 25.9 | 13.3 (3.4) | 81.7 (21.2) | 2.3 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.3) | - | - | - | |

| Ploski | 22.8 | 55.5 (12.7) | 34.3 (7.8) | 8.0 (1.8) | 1.5 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.2) | - | - | - | |

| Rilski manastir | 13.9 | 83.4 (11.6) | - | 11.7 (1.6) | 1.5 (0.2) | 3.4 (0.5) | - | - | - | |

| Sandanski | 13.8 | 72.4 (10.0) | 9.9 (1.4) | 2.2 (0.3) | 14.9 (2.0) | 0.6 (0.1) | - | - | - | |

| Satovcha | 21.2 | 45.1 (9.5) | 38.4 (8.2) | 12.8 (2.7) | 3.3 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.1) | - | - | - | |

| Vetren | 14.9 | 54.2 (8.1) | 13.5 (2.0) | 4.6 (0.7) | 23.3 (3.5) | 4.4 (0.6) | - | - | - | |

| Common (both early and late phenological forms) |

Chirpan | 8.8 | 34.1 (3.0) | - | - | 65.9 (5.8) | - | - | - | - |

| Hisar | 4.1 | 57.2 (2.3) | 22.1 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.1) | 11.4 (0.5) | 7.0 (0.3) | - | - | - | |

| Kazanlak | 11.3 | 77.1 (8.7) | 1.5 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.01) | 14.3 (1.6) | 7.0 (0.8) | - | - | - | |

| Karlovo | 3.0 | 19.7 (0.6) | 66.7 (2.0) | - | 10.6 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.1) | - | - | - | |

| Lesichevo | 13.1 | 68.8 (9.0) | 14.5 (1.9) | 5.7 (0.7) | 11.0 (1.5) | - | - | - | - | |

| Momchilgrad | 4.5 | 0.6 (0.02) | 93.8 (4.2) | 1.9 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.2) | - | - | - | - | |

| Panagyurishte | 7.8 | 90.9 (7.1) | 1.8 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.6) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Peshtera | 6.7 | 52.7 (3.5) | - | 1.6 (0.1) | 45.7 (3.1) | - | - | - | - | |

| Rakitovo | 3.5 | 39.5 (1.4) | - | - | 53.5 (1.9) | 7.0 (0.2) | - | - | - | |

| Dolno Sahrane | 31.6 | 15.9 (5.0) | 75.9 (24.0) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.6) | 4.9 (1.5) | - | - | 0.03 (0.01) | |

| Sladak kladenets | 4.3 | 65.7 (2.8) | - | - | 34.3 (1.5) | - | - | - | - | |

| Zelenikovo | 4.0 | 71.6 (2.9) | 3.3 (0.1) | - | 25.1 (1.0) | - | - | - | - | |

| Zhenda | 24.8 | 52.0 (12.9) | 39.0 (9.7) | 6.4 (1.5) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.3) | - | - | - | |

O. pityocampae had the highest impact (5.77%) on pine processionary moth, followed by B. servadeii (5.69%), A. bifasciatus (1.23%) and Trichogramma sp. (0.52% - Tab. 3). The other three species of primary parasitoids (P. bruchicida, E. vladimiri and E. vesicularis) had a negligible impact on the host. They were found only in old habitats of T. pityocampa (Tab. 3).

Tab. 3 - Average impact (%) of egg parasitoids of T. pityocampa in different zones of its range in Bulgaria.

| Species | Total (n=44) |

Early form habitats (n=12) |

Late form habitats (n=19) |

Both early and late form habitats (n=13) |

Old habitats (n=34) |

New habitats (n=10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O. pityocampae | 5.77 ± 0.78 | 3.12 ± 1.06 | 8.27 ± 1.34 | 4.56 ± 1.06 | 6.02 ± 0.94 | 4.92 ± 1.32 |

| B. servadeii | 5.69± 1.16 | 9.30 ± 2.95 | 5.04 ± 1.32 | 3.32 ± 1.88 | 7.20 ± 1.40 | 0.54 ± 0.24 |

| B. transversalis | 0.56 ± 0.09 | 0.40 ± 0.12 | 0.85 ± 0.16 | 0.28 ± 0.12 | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 0.20 ± 0.10 |

| A. bifasciatus | 1.23 ± 0.25 | 1.14 ±0 .66 | 1.17 ± 0.28 | 1.42 ± 0.44 | 1.12 ± 0.27 | 1.62 ± 0.56 |

| Trichogramma sp. | 0.52 ± 0.21 | 0.79 ± 0.74 | 0.54 ± 0.16 | 0.25 ± 0.12 | 0.30 ± 0.09 | 1.28 ± 0.87 |

| P. bruchicida | 0.0048 ± 0.0026 | 0.0025 ± 0.0018 | 0.0095 ± 0.0058 | 0 | 0.0062 ± 0.0033 | 0 |

| E. vladimiri | 0.0068 ± 0.0068 | 0.0250 ± 0.0250 | 0 | 0 | 0.0088 ± 0.0088 | 0 |

| E.vesicularis | 0.0032 ± 0.0024 | 0.0025 ± 0.0025 | 0.0053 ± 0.0053 | 0.0008±0.0008 | 0.0041 ± 0.0031 | 0 |

| All species | 13.79 ±1.25 | 14.79 ± 2.89 | 15.89 ± 1.35 | 9.81 ± 2.45 | 15.33 ± 1.46 | 8.56 ± 1.52 |

The impact of egg parasitoids on the numbers of the pine processionary moth varied within a fairly wide range in different localities, from 0.3% (Hvoina) to 31.6% (Dolno Sahrane - Tab. 2).

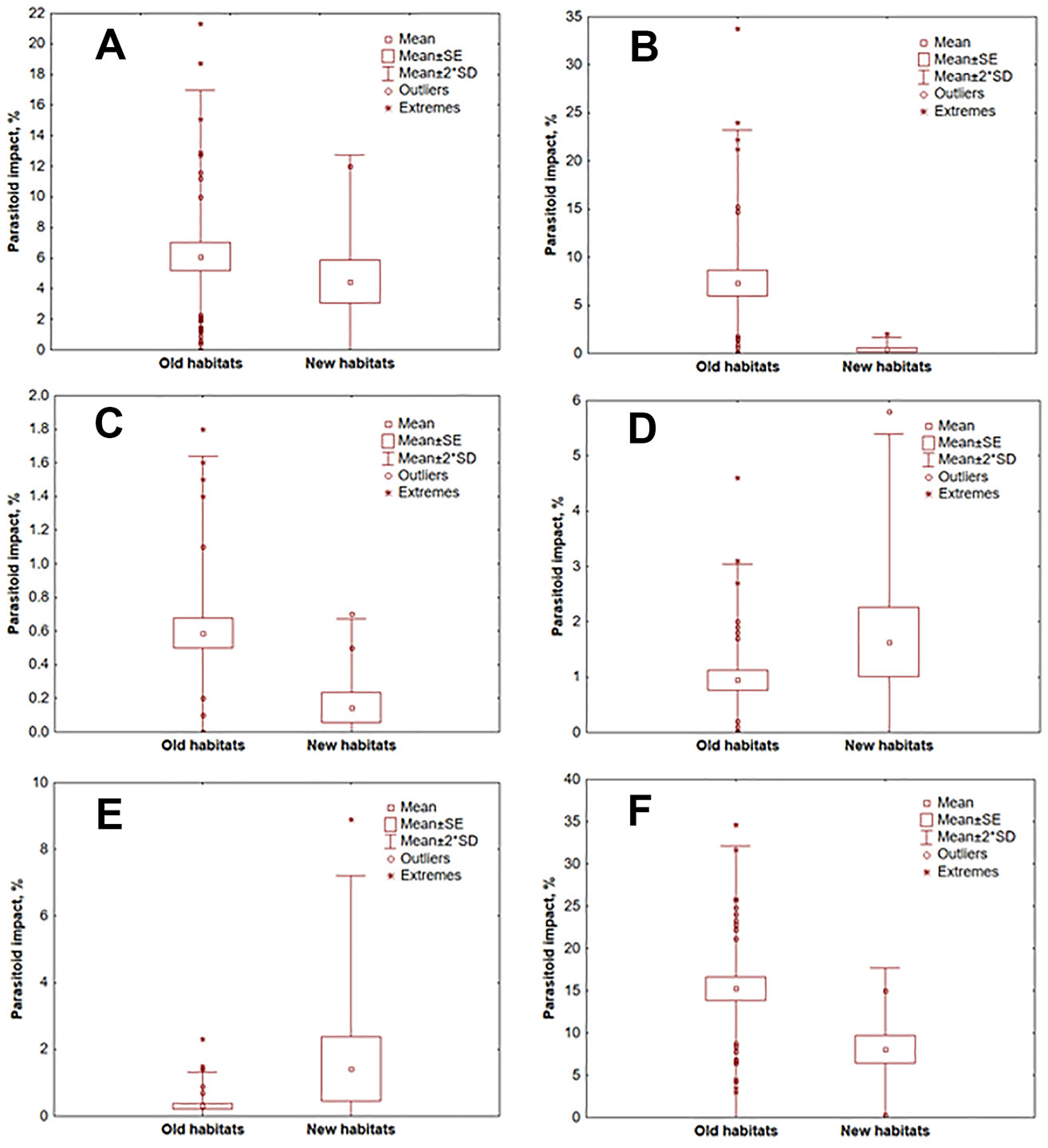

In old habitats, the greatest impact on T. pityocampa was due to B. servadeii (7.20% - Fig. 2B), followed by O. pityocampae (6.02% - Fig. 2A), A. bifasciatus (1.12% - Fig. 2D) and Trichogramma sp. (0.30% - Fig. 2E). In newly occupied habitats, the most important was O. pityocampae (4.92% - Fig. 2A), followed by A. bifasciatus (1.62% - Fig. 2D), Trichogramma sp. (1.28% - Fig. 2E) and B. servadeii (0.54% - Fig. 2B). The differences in the parasitoid impact in these two type of areas are statistically significant for B. servadeii (p = 0.017) and Trichogramma sp. (p = 0.045), as well as for the hyperparasitoid B. transversalis (0.67% and 0.20%, respectively; p = 0.013 - Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2 - Impact of egg parasitoids in different zones of T. pityocampa range. (A): O. pityocampae; (B): B. servadeii; (C): B. transversalis; (D): A. bifasciatus; (E): Trichogramma sp.; (F): All parasitoid species.

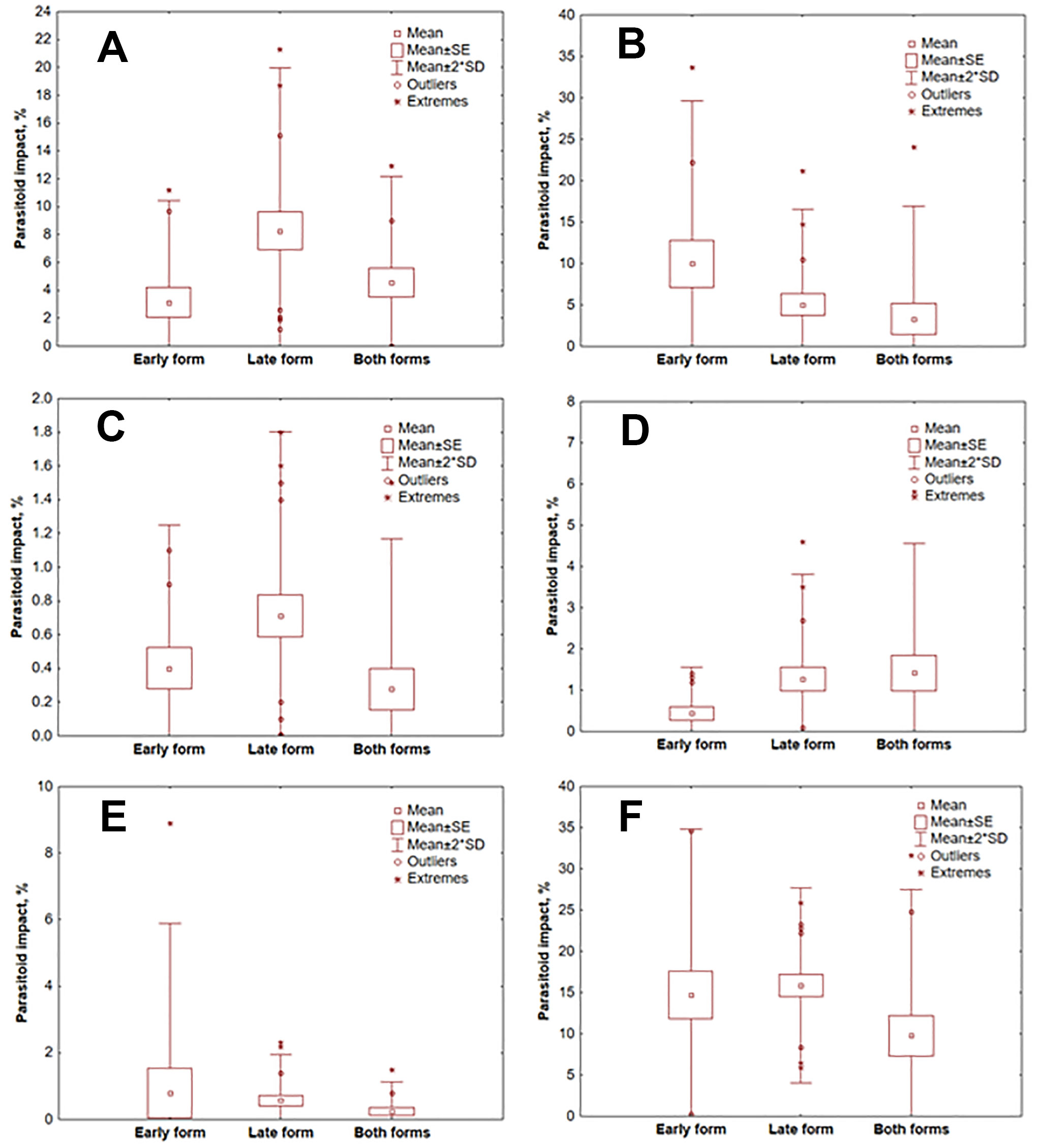

Significant differences of impact between early and late phenological forms of T. pityocampa were observed for two polyphagous species: O. pityocampae (3.12% and 8.27%, respectively; p = 0.012 - Fig. 3A) and A. bifasciatus (1.14% and 1.17%; p = 0.033 - Fig. 3D). The data on habitats colonized by both early and late forms are difficult to interpret, so statistical evaluation was only carried out for pure habitats (either early or late form habitats).

Fig. 3 - Impact of egg parasitoids on different phenological forms of T. pityocampa. (A): O. pityocampae; (B): B. servadeii; (C): B. transversalis; (D): A. bifasciatus; (E): Trichogramma sp.; (F): All parasitoid species.

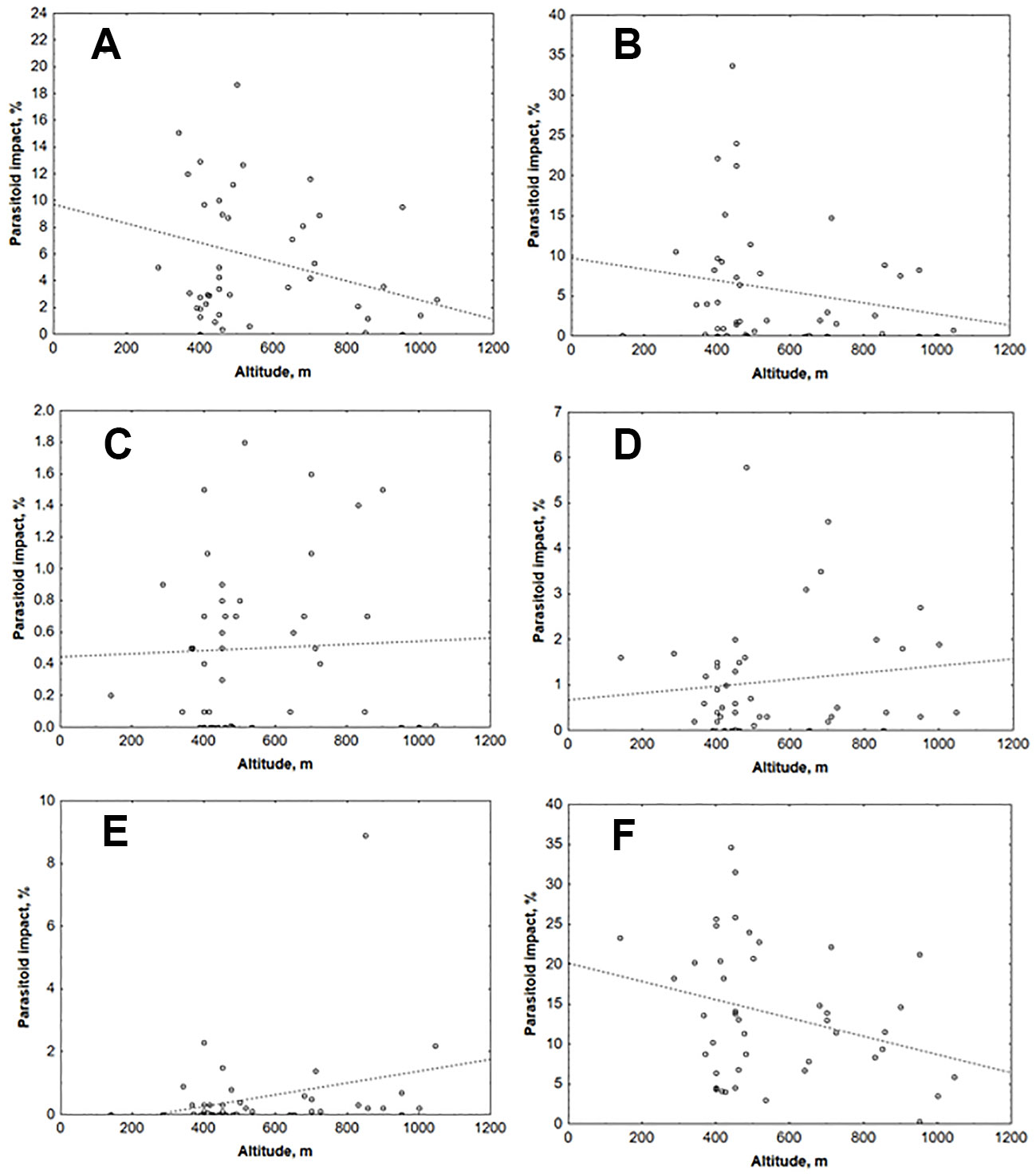

The relationship between the impact of parasitoids and the altitude of studied sites was analysed for five parasitoid species of T. pityocampa (Fig. 4). The rare parasitoids P. bruchicida, E. vladimiri, and E. vesicularis were excluded because only single specimens were found in a limited number of sites. The correlation between the impact of parasitoids and habitat elevation was not significant, with R2 varying between 0.022 (A. bifasciatus) and 0.203 (O. pityocampae). In addition, no differences in altitude distribution trends of the two main parasitoids of T. pityocampa (O. pityocampae - Fig. 4A; B. servadeii - Fig. 4B) were established.

Fig. 4 - Influence of altitude on impact of egg parasitoids of T. pityocampa. (A): O. pityocampae; (B): B.servadeii; (C): B. transversalis; (D): A. bifasciatus; (E): Trichogramma sp.; (F): All parasitoid species.

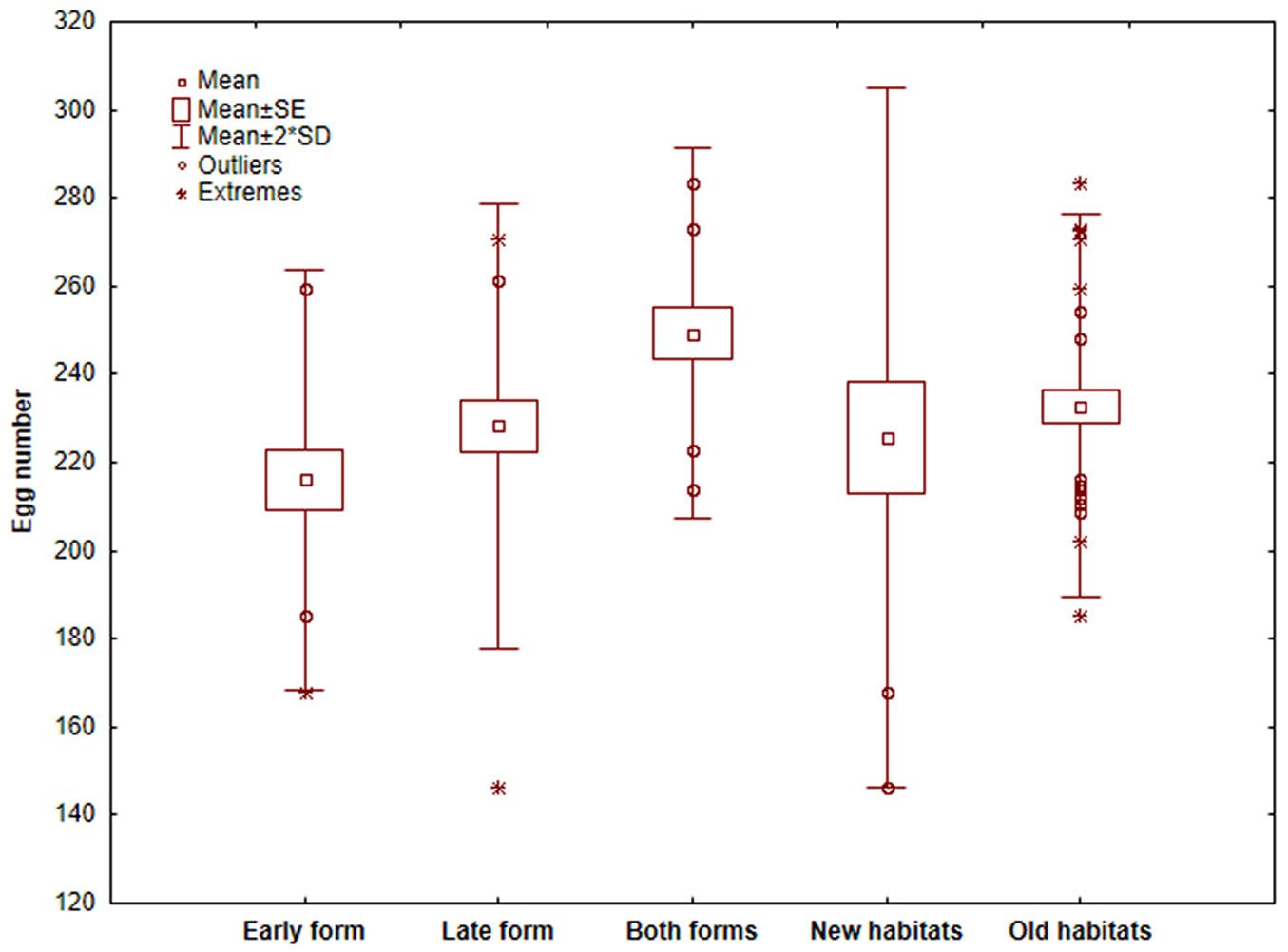

The studies on the parasitoids were conducted with comparable fertility and habitat characteristics of pine processionary moth. We found a small but significant difference in the average number of eggs per batch between early and late forms of T. pityocampa (209.16 ± 10.06 vs. 228.26 ± 5.79, respectively; p = 0.23), and between the new and old habitats of the species (225.64 ± 12.56 vs. 230.36 ± 4.80, respectively; p = 0.46 - Fig. 5). However, there was a significant difference in the average number of eggs of sites with both forms of pine processionary moth (249.35 ± 5.82), compared to the early form (p = 0.001) and the late form (p = 0.02) habitats.

The average altitude of the habitats in the expansion zone of T. pityocampa (429.00 ± 21.99 m a.s.l.) was lower than that of the habitats in its historical range (569 ± 35.28 m a.s.l.). This was expected, given that the expansion zone is located more northwards than the historical zone, on average (Fig. 1). Such difference seems unlikely to be explained by the lack of sampling sites at high altitudes, as the expansion develops on the southern slope of Stara Planina, whose main ridges reach elevations not suitable to this pest.

The hyperparasitoid B. transversalis developed on O. pityocampae and B. servadeii. Among the studied habitats, B. transversalis was not detected in nine locations (20.5%): four in sites with early form, and five in sites with both early and late forms (Tab. 2). The impact on primary parasitoids varied widely among sites from 0% up to 29.6% (Gotse Delchev). In nine localities, the impact on the number of primary parasitoids was above 10.0%, while it was between 5.1% and 10.0% in further nine localities, and below 5.0% in the remaining 26 localities. As for the relative share of B. transversalis in the total egg parasitoid complex of T. pityocampa in Bulgaria, it varied between 1.1% and 4.8%, with the lowest value in the new habitats (Tab. 3).

Discussion

The results of this study showed that B. servadeii and O. pityocampae are the two most important egg parasitoids of pine processionary moth in Bulgaria. Both species are major egg parasitoids of the host in all its range ([3], [14], [27]), as well as of Thaumetopoea bonjeani Powell, 1922 and Thaumetopoea wilkinsoni Tams, 1926 (Lepidoptera: Notodontidae) in cedar forests ([3], [1], [26]).

Generally, the specialist B. servadeii is dominant in old habitats and habitats of the early phenological form of T. pityocampa, while the generalist O. pityocampae is dominant in new habitats and in habitats of the late form, as well as in habitats of both phenological forms. In new habitats, the polyphagous species A. bifasciatus and Trichogramma sp. can be also dominant in some cases. Such characteristics of distribution and impact of egg parasitoids of T. pityocampa have been recently recorded in case studies in Bulgaria and France ([21], [24], [9]).

The percentage of parasitism caused by O. pityocampae and B. servadeii does not depend on location of T. pityocampa egg batches on pine needles ([12]). Masutti ([16]) pointed out that B. servadeii is more resilient and develops successfully in areas with temperatures above 30 °C, i.e., in conditions that suppress O. pityocampae development. According to Tiberi ([34]), in Italy B. servadeii is most abundant in the warmer regions of the central and southern part of the country. However, the abundance and importance of the parasitoids depend not only on the temperature conditions of the habitats. In Algeria, the maximum summer temperature frequently exceeded 40 °C during the period of adult activity of O. pityocampae and B. servadeii, but no correlation with parasitism rates on T. pityocampa has been observed ([6]). Mirchev ([19]) suggested that the rich floral diversity of habitats contributes to successful survival of the generalist O. pityocampae by creating favourable conditions for the presence and development of alternative hosts. This hypothesis could explain the drastic differences in parasitism rates of O. pityocampae and B. servadeii in Marikostinovo and Parvomay, which are nearby sites in southwestern Bulgaria with a strong Mediterranean influence. This assumption is supported by the results of studies carried out in Algeria, where a positive correlation between the proportion of agricultural areas and the parasitism by O. pityocampae was established ([6]). In support of this, in the region of Marikostinovo the share of agricultural land is significantly higher than in Parvomay, where forests predominate. On the other hand, Marikostinovo is 270 m lower in elevation than Parvomay (Tab. 1), and the average temperatures there should be quite higher, i.e., more favorable for B. servadeii. Nevertheless, in Marikostinovo it is O. pityocampae that definitely dominates (91% of the infested eggs), while in Parvomay B. servadeii predominates (82% of the infested eggs - Tab. 2).

A higher relative abundance of B. servadeii has been reported in the Eastern Rhodopes, where the early phenological form is widespread ([23]). In this form, the female moths lay eggs about two months earlier than the typical late form. In laboratory conditions, the emergence of B. servadeii begins well before the period of laying eggs of T. pityocampa late (“winter”) phenological form ([40]). With this in mind, the higher parasitism of the specialist B. servadeii in the early (“summer”) phenological form of the host was expected. The significantly higher impact of B. servadeii in old habitats was also expected due to the time required for this specialized parasitoid to colonize the site after the host penetration. Indeed, it is known that B. servadeii tracks the host in the expansion range, ensuring a relatively quick density-dependent control ([2]). However, the reduced genetic diversity of B. servadeii could negatively affect its ability to adapt to the new environments colonized by its host, thus reducing the efficiency of biological control ([32]).

The higher impact of the polyphagous polyvoltine generalist O. pityocampae and A. bifasciatus in late phenological form of T. pityocampa, as well as Trichogramma sp. in newly colonized areas, could be explained with the possibility of gradual multiplication on alternative hosts in the studied habitats.

In recent decades, the expansion of T. pityocampa range to higher latitude and elevation due to climate change has been observed ([3], [2]). As for the two main parasitoid species of pine processonary moth (O. pityocampae and B. servadeii), a decrease in parasitism rate with elevation has been established in a mountain range of Sierra Nevada (South-eastern Andalusia, Spain), with more severe decline for the specialist B. servadeii ([13]). In Bulgaria, the impact of O. pityocampae and B. servadeii also decreases at higher altitude, however it is not entirely negligible even near the upper limits of the host elevation range (about 1200 m a.s.l.). Conversely, the effectiveness of the other two significant parasitoids (A. bifasciatus and Trichogramma sp.) increases with increasing altitude, probably due to the reduced competition from O. pityocampae and B. servadeii. This demonstrates their resilience and their ability to develop over a wider range of ambient temperatures.

In some habitats, the hyperparasitoid B. transversalis severely limits (up to 29.6%) the number of primary parasitoids O. pityocampae and B. servadeii. The species is known from Greece ([30], [41]) and other countries on the Balkan Peninsula: Bulgaria ([40]), Albania ([17]) and Bosnia and Herzegovina ([7]). It was also established on the Iberian Peninsula ([15]) and the Asiatic part of Turkey ([18]). The information that B. transversalis prefers B. servadeii ([4], [5]) is not supported by other studies where no clear host selectivity has been established ([19]). The impact of the hyperparasitoid on the two primary parasitoids is known to vary widely, from 0.5-3.0% ([40], [30]) to 23.6% ([17]). These data are fully consistent with the results of the present study and confirm the conclusion that there is great variability in the impact of the hyperparasitoid on the numbers of O. pityocampae and B. servadeii in different habitats.

Conclusions

Our results confirmed O. pityocampae and B. servadeii to be the two main egg parasitoids of pine processionary moth in Bulgaria. All the other parasitoids, mainly A. bifasciatus and Trichogramma sp., have a noticeable share (up to 33% of the parasitised eggs) only in areas recently colonized by T. pityocampa.

In old habitats of T. pityocampa (colonized more than 10 years ago), the impact of parasitoids is almost 2 times higher (15.3%) than in newly colonized areas (8.6%). This is due to the specialist B. servadeii, which is rare in newly colonized areas (0.54%), but strongly dominates in long-established ones (7.2%). In new habitats of the host, the generalist O. pityocampae dominates (4.9%). B. servadeii definitely dominates in the habitats of T. pityocampa early form (>50% of the parasitised eggs), while in the late form of the host, O. pityocampae dominates (>50% of the parasitised eggs). This difference is likely due to the phenological characteristics of the parasitoids and the host. The impact of the two most important species, O. pityocampae and B. servadeii, and the parasitoid complex as a whole decreases with altitude. On the contrary, the impact of A. bifasciatus and Trichogramma sp. slightly increases with altitude, which might indicate their suppression by the main parasitoids.

In general, the parasitism of T. pityocampa eggs is a complex process that depends not only on the time of adaptation and the coincidence of the phenology of parasitoids to the phenology of the host, but also on many other factors such as population density of the pest, age and density of pine stands, local plant biodiversity, exposure, temperature conditions of the habitats, etc. Clarifying the complex influence of these factors is extremely important for the choice of silvicultural activities that would contribute to increasing the effectiveness of the parasitoids.

Acknowledgements

This work has been carried out in the framework of the National Science Program “Environmental Protection and Reduction of Risks of Adverse Events and Natural Disasters”, approved by the Resolution of the Council of Ministers no. 577/17.08.2018 and supported by the Ministry of Education and Science (MES) of Bulgaria (Agreement no. D01-363/17.12.20 20).

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Georgi Georgiev 0000-0001-5703-2597

Margarita Georgieva 0000-0003-3165-1992

Ivailo Markoff 0000-0002-8725-557X

Gergana Zaemdzhikova

Maria Matova

Forest Research Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia (Bulgaria)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Mirchev P, Georgiev G, Georgieva M, Markoff I, Zaemdzhikova G, Matova M (2021). Abundance and impact of egg parasitoids on the pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa) in Bulgaria. iForest 14: 456-464. - doi: 10.3832/ifor3538-014

Academic Editor

Massimo Faccoli

Paper history

Received: May 29, 2020

Accepted: Aug 07, 2021

First online: Oct 02, 2021

Publication Date: Oct 31, 2021

Publication Time: 1.87 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2021

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 31323

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 26800

Abstract Page Views: 1860

PDF Downloads: 2084

Citation/Reference Downloads: 5

XML Downloads: 574

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 1593

Overall contacts: 31323

Avg. contacts per week: 137.64

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2021): 2

Average cites per year: 0.40

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Effects of defoliation by the pine processionary moth Thaumetopoea pityocampa on biomass growth of young stands of Pinus pinaster in northern Portugal

vol. 3, pp. 159-162 (online: 15 November 2010)

Research Articles

The impact of post-defoliation foliage of Pinus halepensis Mill. on the larval performance of Thaumetopoea pityocampa and its relationship with the tree-induced defense

vol. 18, pp. 186-193 (online: 01 July 2025)

Research Articles

Plant phenotype affects oviposition behaviour of pine processionary moth and egg survival at the southern edge of its range

vol. 11, pp. 572-576 (online: 01 September 2018)

Research Articles

Performances of an expanding insect under elevated CO2 and snow cover in the Alps

vol. 1, pp. 126-131 (online: 27 August 2008)

Research Articles

Predicting phenology of European beech in forest habitats

vol. 11, pp. 41-47 (online: 09 January 2018)

Research Articles

Landsat TM imagery and NDVI differencing to detect vegetation change: assessing natural forest expansion in Basilicata, southern Italy

vol. 7, pp. 75-84 (online: 18 December 2013)

Technical Reports

Population genetic structure of Platanus orientalis L. in Bulgaria

vol. 4, pp. 186-189 (online: 11 August 2011)

Research Articles

Change Detection methods for forest expansion assessment in the last twenty years in the Mediterranean Basin

vol. 18, pp. 69-78 (online: 16 April 2025)

Research Articles

Distribution and habitat suitability of two rare saproxylic beetles in Croatia - a piece of puzzle missing for South-Eastern Europe

vol. 11, pp. 765-774 (online: 28 November 2018)

Research Articles

Integrating conservation objectives into forest management: coppice management and forest habitats in Natura 2000 sites

vol. 9, pp. 560-568 (online: 12 May 2016)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword