Distribution of aluminium fractions in acid forest soils: influence of vegetation changes

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 11, Issue 6, Pages 721-727 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor2498-011

Published: Nov 06, 2018 - Copyright © 2018 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

This study examines aluminium as a potentially phytotoxic element in acidic forest soils. Concentrations of Al forms in soils are generally controlled by soil chemical conditions, such as pH, organic matter, base cation contents, etc. Moreover, soil conditions are influenced by the vegetation cover. This study analyzed the distribution of Al forms in soils after changes in vegetation. HPLC/IC was used for the separation of three Al fractions in two soil extracts according to their charge. An aqueous extract (AlH2O) simulated the natural soil conditions and bioavailable Al fractions. Potentially available Al form was represented by a 0.5 M KCl extract (AlKCl). We demonstrated that the vegetation type influences the concentrations of different Al fractions, mainly in the surface organic horizons. Differences were more common in the KCl extract. The trivalent fraction was less influenced by vegetation changes than the mono- and divalent fractions. Afforestation increased the concentrations of AlKCl and AlH2O. In contrast, grass expansion after deforestation led to significantly decreased concentrations of AlKCl and AlH2O. Concentrations of AlH2O in organic horizons were higher in spruce forest than in beech forest. A long-term effect of liming on soil pH and concentrations of potentially toxic Al fractions was not apparent. The results provide information on the variations of Al fractions distributions following vegetation type changes and indicate the existence of some natural mechanisms controlling Al toxicity. Furthermore, the results can be used in the management of forested areas endangered by soil acidification.

Keywords

Aluminium Fractionation, Forest Soil, Afforestation, Deforestation, HPLC/IC

Introduction

Aluminium is one of the more abundant elements in soils, making up approximately 7% of its inorganic matter ([40]). Primary and secondary aluminosilicates are the main sources of Al in soils. Aluminium is mobilized by chemical or biochemical weathering and creates different dissolved ion fractions, which depend on the pH of the soil solution ([34]). Mineral weathering of aluminosilicates is very slow, but the presence of organic compounds leads to higher weathering rates and to the formation of soluble Al complexes with organic molecules ([36], [46], [18]). Therefore, Al occurs in soils and soil waters in many forms or fractions. The fractions of dissolved Al determine its potential bioavailability and toxicity. Toxicity to plants decreases qualitatively in the order: Al13 (not in a form of phosphates or silicates), Al3+, Al(OH)2+, Al(OH)2+. Aluminium bound with organic complexes has been found to be nontoxic ([40]). Therefore, the complexation of Al by natural organic ligands is important for regulating concentrations of the highly toxic Al3+ ion in acid soils and natural waters ([47], [10]).

A significant change in the biogeochemical cycling of Al has resulted from the man-made acidification of the environment ([17]). Past extensive acid deposition ([25]) of strong acids (sulfuric or nitric), has accelerated the release of Al from aluminosilicates and secondary Al soil phases. Higher sulfate content affects soil acidity and transforms hydroxylated Al fractions to Al3+ ([33], [39], [23]). A strong negative correlation between the concentration of exchangeable Al in soils and the level of SO42- deposition in the O horizon were demonstrated by Lawrence et al. ([26]). Additionally, strong acid anions increase the release of Al-organic complexes in spodic soil horizons ([48]). Soil waters of anthropogenically acidified areas thus have a higher content of ionic and toxic Al forms. This situation is typical of the northern parts of the Czech Republic ([41]). Mountainous forests in the top parts of the mountains were damaged directly by acid rain and SO2 fumigation in the past. Large-scale forest dieback, followed by grass expansion, has occurred. Damage to soils by anthropogenic acidification is related to a low content of base cations, a very acidic character of soils, and abundant mobile Al forms ([4]). These conditions have made forest recovery difficult, including at present. Amelioration by forest liming has been attempted in these areas. Our previous studies ([31], [5]) reported that the distribution of Al forms in soils is controlled by pH. The pH value can be conditioned by the natural presence of Ca or Mg carbonate minerals, or it can be regulated by adding limestone. Organic matter plays a role in Al distribution by providing sorption and binding sites ([33]).

At altitudes below approximately 800 m a.s.l., natural forest cover in the Czech Republic consists of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) or mixed beech-spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst.) forests. In the past, these natural forests were widely transformed into spruce monocultures, which also can accelerate acidification processes ([2], [12]).

Many combinations of effects exist in the natural soil environment, and the final Al distribution is controlled by many factors. Drábek et al. ([14]) and Brandtberg & Simonsson ([9]) showed marked differences in Al fractions distribution among soils of cropland, grassland, and forest, and also between different forest types. The aim of this research is to study the relationships between the dissolved or potentially soluble Al fraction distribution and land-use changes (afforestation, deforestation, amelioration). The main hypothesis is that land-use change impacts the Al fraction distribution in soil. The second hypothesis is that the effect of acid soil amelioration results in a long-term decrease of dissolved Al concentrations in soil.

Methods

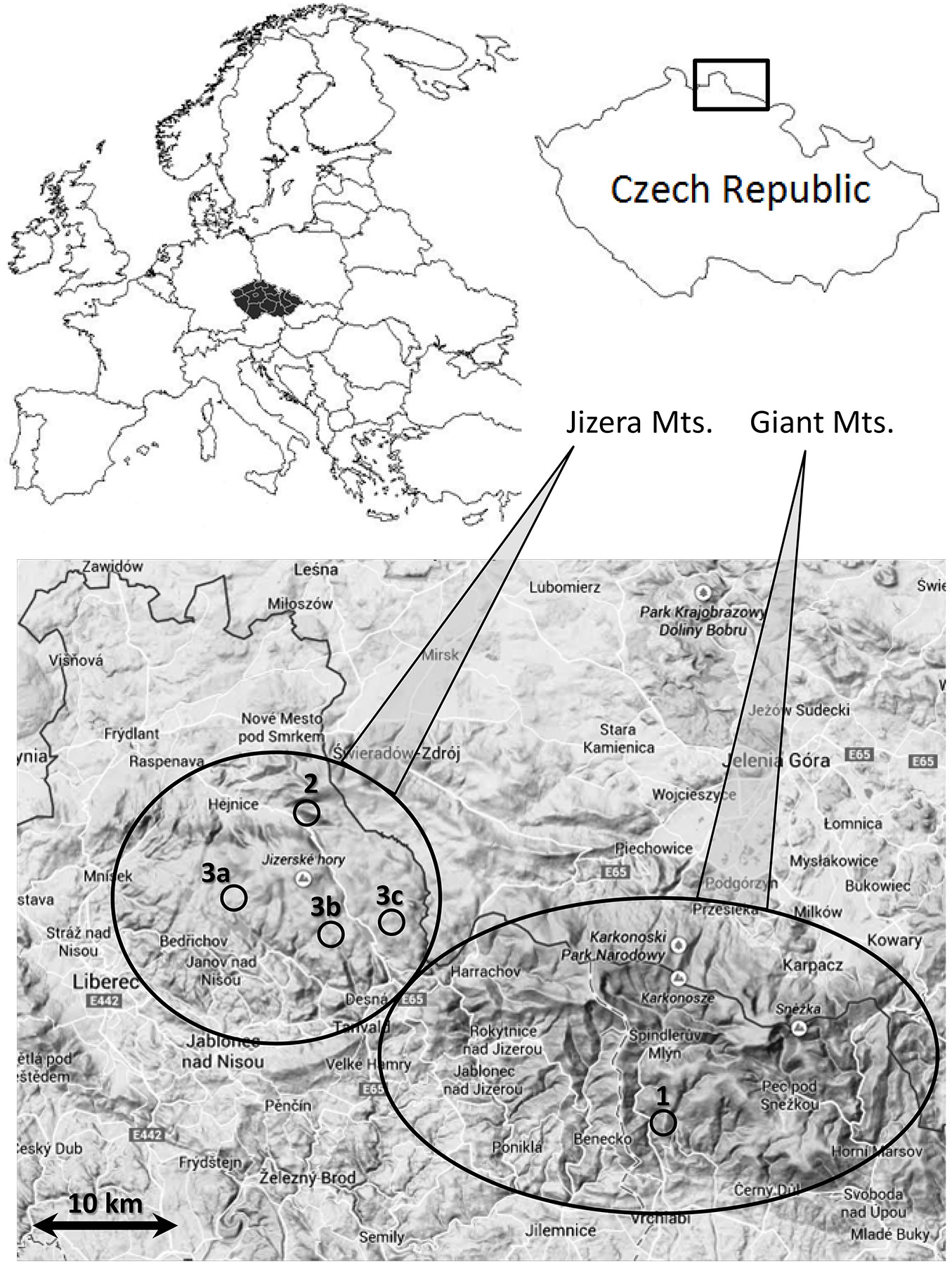

This paper reports findings from three separate projects on aluminium fractionation in soils. These projects were located in two mountainous areas in the north of the Czech Republic (Fig. 1), where soil acidification has been observed and studied ([16], [13], [7]). The altitude of the Jizera Mountains ranges between 400 and 1100 m a.s.l., and the altitude of Giant Mountains ranges between 400 and 1600 m. In both areas, the average annual precipitation is between 1200 and 1300 mm, and the average annual temperature is 4-7 °C. Precipitation and temperature are naturally altitude-dependent. The Jizera Mts. are underlaid by homogenous granite, while the Giant Mts. geology is more variable. At higher elevation, the bedrock is of the same granite massif as in the Jizera Mts. At lower elevation, the bedrock consists of gneiss, schist, and phyllites.

Fig. 1 - Sampling sites localization. (1): afforestation study; (2): forest type study; (3a, b, c): deforestation and liming study.

The afforestation study (1) in the Giant Mts. (Fig. 1) focused on the comparison among meadow, afforested meadow (50-year-old Norway spruce, and an old-growth Norway spruce forest. All sampling areas are on gneiss bedrock, and single variants are in close vicinity. In each vegetation cover variant, soil pits were dug (4, 4, and 3, respectively), and soil samples were collected (described in detail by [13]).

The study on forest type change (2) obtained results from two long-term monitoring plots in the Jizera Mts. (630-680 m a.s.l. - Fig. 1), described in detail by [7]. The first plot is covered by an old-growth beech forest, typical for that location, and the second one is covered by a 100-year-old Norway spruce forest, which had artificially replaced a beech forest. Sampling occurred monthly from April to October during the years 2008-2011 (three soil pits per forest type in each month).

The deforestation and amelioration study (3) was conducted in the higher parts of the Jizera Mts. (800-900 m a.s.l. - Fig. 1), where the forest died in the 1980s due to acid rain, and the resulting change in the lighting conditions led to the expansion of the grass. For several decades, a large area was covered by grasses (Calamagrostis villosa [Chaix] J. F. Gmel., Deschampsia flexuosa [L.] Drejer) and was difficult to reforest. Liming was used to counter the effects of soil acidification from acid rain. Our study compared soil conditions of the soils still covered by grass (control), those covered by grass with amelioration by dolomitic limestone (once, 2 t ha-1) 25 years before sample collection (limed), and those covered by more than 40-year-old Norway spruce native forest (forest). Results represent the analysis of 9 soil pits in each variant (3 isolated plots - 3a, b, and c in Fig. 1), where all 3 variants are in close proximity and sampled by 3 soil pits each.

Soil sampling was very similar in all studies. Soil pits, approximately 50 × 50 cm, were excavated for soil description and sample collection. Soils were classified by IUSS Working Group ([22]), mostly as Cambisols or Podzols. Samples from all sufficiently thick horizons were collected. In most cases, surface organic horizons (F: fermentation horizons; H: humified horizons), organomineral humic horizons (A), eluvial albic horizons (Ep), spodic horizons (Bspod), cambic horizons (Bv), and substrate horizons (C) were present. Samples were air dried and sieved to <2 mm, and basic soil characteristics were determined. Active and exchangeable pH (pHH2O and pHKCl, respectively) were determined potentiometrically by ion-selective electrode. Ca (CaAR) and Mg (MgAR) were determined after soil digestion with aqua regia by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS - Varian SpectrAA-200®, VARIAN, Australia). Effective cation exchange capacity (eCEC) of mineral horizons was determined by the Mehlich method with unbuffered 0.1 M BaCl2 extraction solution ([35]). Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was determined by the Bower method, with Na+ as an index ion ([19]); Na in the extract solution was determined by AAS.

A method of Al fractionation in deionized water and 0.5 M KCl extract by HPLC/IC was used ([15]). This method enables Al fractions to be separated into three different groups according to their charge: Al(X)1+ [i.e., Al(OH)2+, Al(SO4)+, AlF2+, Al(oxalate)+, Al(H-citrate)+, etc.]; Al(Y)2+ [Al(OH)2+, (AlF)2+, etc.]; and Al3+ (Al3+ and transformed hydroxyl Al polymers). However, Al(X)1+ fractions co-elute with Al(Z)≤0 fractions, where Z represents mainly organic ligands. The sum of the fractions in aqueous extracts is designated AlH2O, and that of the KCl extracts is AlKCl. A modified methodology of Al fractionation was used in the study on forest type change (2). This study also focused on the distribution of dissolved organic carbon (DOC - [42]), and the sample processing was adjusted to apply to DOC measurements ([24]). Fresh, unsieved soil samples were used, and only the aqueous extract was analyzed. Therefore, the concentrations of all studied Al fractions are lower than those from the other studies.

Statistical analysis, one-way analysis of variance, t-test, and paired t-test were performed using STATISTICA® v. 9.1 software (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

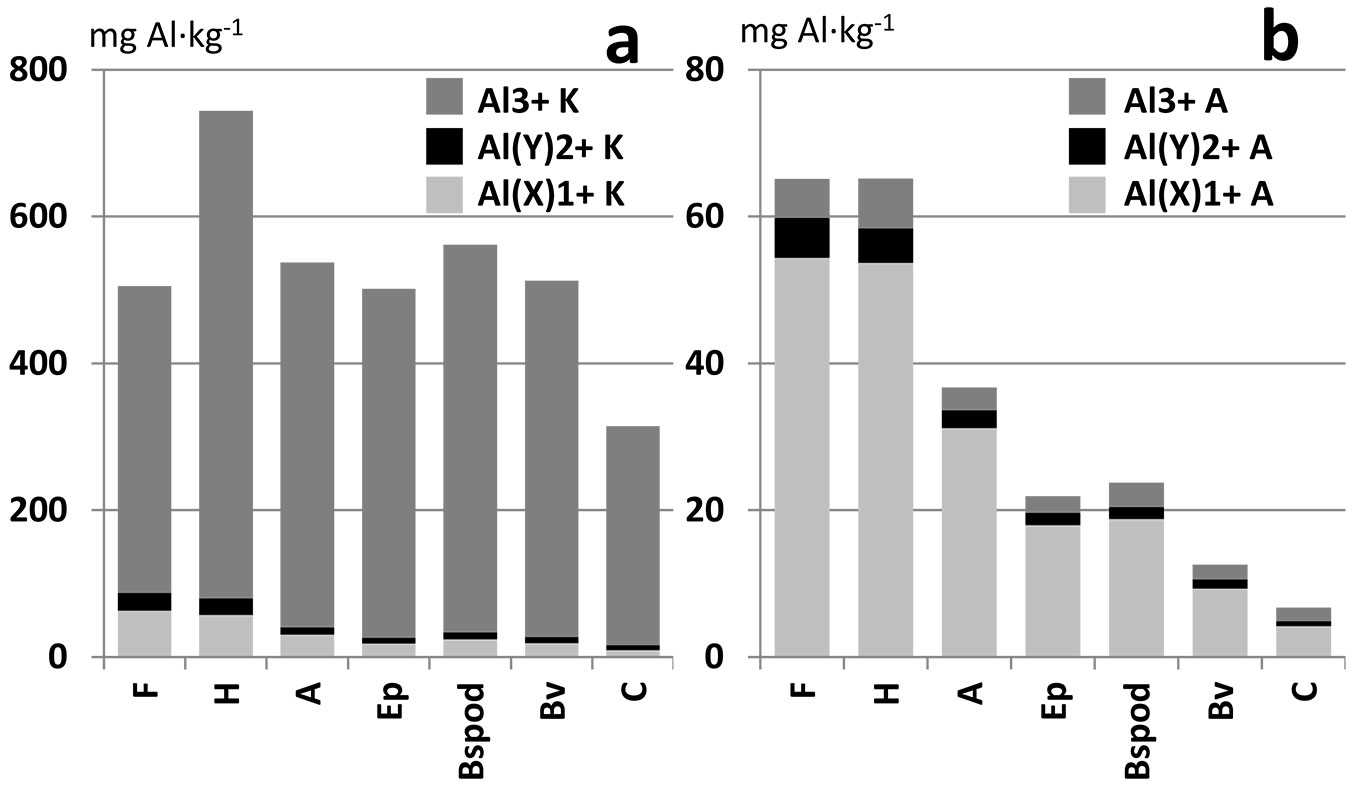

All presented graphs (Figs. 2 to 5) show that KCl extracts had approximately 10 times more Al than deionized water. The relative distribution of the studied fractions also differs between extracts. The dominant fraction in KCl is Al3+ and in the water extract it is Al(X)1+.

Generally, all presented studies were located in mountainous areas with acidic bedrock, representing areas strongly affected by soil acidification. The prevailing soil types in these areas are dystric Cambisols in the lower parts, and Podzols in the upper parts of the mountains. The differences in Al fraction distribution in the soil profiles of both these soil types are presented in Fig. 2 and Tab. S1 (Supplementary material).

Fig. 2 - Distribution of Al fractions in soil horizons (a) in KCl extract, and (b) in aqueous extract). Average values of all samples from Jizera Mts. and Giant Mts.

Afforestation effect

Basic soil characteristics of meadow, young (50 years old) forest on former meadow, and native forest soils are shown in Tab. 1. There are clear differences among these three plots according to the described soil type. Cambisol was found in the meadow and young forest plots, whereas, on the original forest plot, Podzol with very well-defined diagnostic horizons was recognized. The strong-acid character of forest soil compared to other plots is also apparent. Cation exchange capacity is generally associated with organic matter in soils, and it decreases from organic to mineral soil horizons. Spodic horizons are enriched by organic compounds, and CEC follows this trend. The statistical comparison of vegetation cover variants in the sampled soil horizons is shown in Tab. 2.

Tab. 1 - Average values of basic soil characteristics for separate soil horizons. (M): scythed meadow in forest vicinity; (F 50): 50 years old forest planted on former meadow; (F): old growth forest.

| Variant | Soil type | Horizon | pHH2O | pHKCl | CEC (mmol 100 g-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | cambisol | A | 4.79 | 3.38 | 26.13 |

| Bv | 4.90 | 3.56 | 18.06 | ||

| F50 | cambisol | F | 3.80 | 2.79 | 50.38 |

| A | 3.83 | 2.91 | 24.13 | ||

| Bv | 4.16 | 3.23 | 16.81 | ||

| F | podzol | F | 3.17 | 2.05 | 140.83 |

| H | 3.11 | 2.01 | 92.00 | ||

| Ep | 3.53 | 2.35 | 8.58 | ||

| Bspod | 3.68 | 3.04 | 47.07 |

Tab. 2 - Results of t-test (t-values of the differences) comparing the distribution of basic soil characteristics and Al fractions (K: in KCl extract; A: in aqueous extract) in selected soil horizons of three vegetation cover types. (M): scythed meadow in forest vicinity; (F50): 50-year-old forest planted on former meadow; (F): old growth forest.

| Variable | F horizon (F50 × F) |

A horizon (M × F50) |

Bv horizon (M × F50) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | Prob | t | Prob | t | Prob | |

| pHH2O | 8.13 | <0.001 | 6.87 | 0.001 | 3.55 | 0.012 |

| pHKCl | 8.90 | <0.001 | 5.76 | <0.001 | 2.43 | 0.051 |

| CEC | -4.23 | 0.008 | 1.77 | 0.128 | 0.77 | 0.473 |

| Al(X)1+K | -4.72 | 0.005 | -9.40 | 0.003 | -2.76 | 0.070 |

| Al(Y)2+K | -4.77 | 0.005 | 1.46 | 0.240 | -0.95 | 0.413 |

| Al3+K | -2.02 | 0.090 | -4.09 | 0.026 | -1.42 | 0.251 |

| AlKCl | -2.30 | 0.070 | -4.19 | 0.025 | -1.50 | 0.231 |

| Al(X)1+A | 2.69 | 0.043 | -6.70 | 0.007 | -3.08 | 0.054 |

| Al(Y)2+A | 0.29 | 0.781 | -2.50 | 0.087 | -4.42 | 0.022 |

| Al3+A | 0.65 | 0.544 | -5.37 | 0.013 | -2.79 | 0.068 |

| AlH2O | 2.36 | 0.065 | -6.73 | 0.007 | -3.57 | 0.038 |

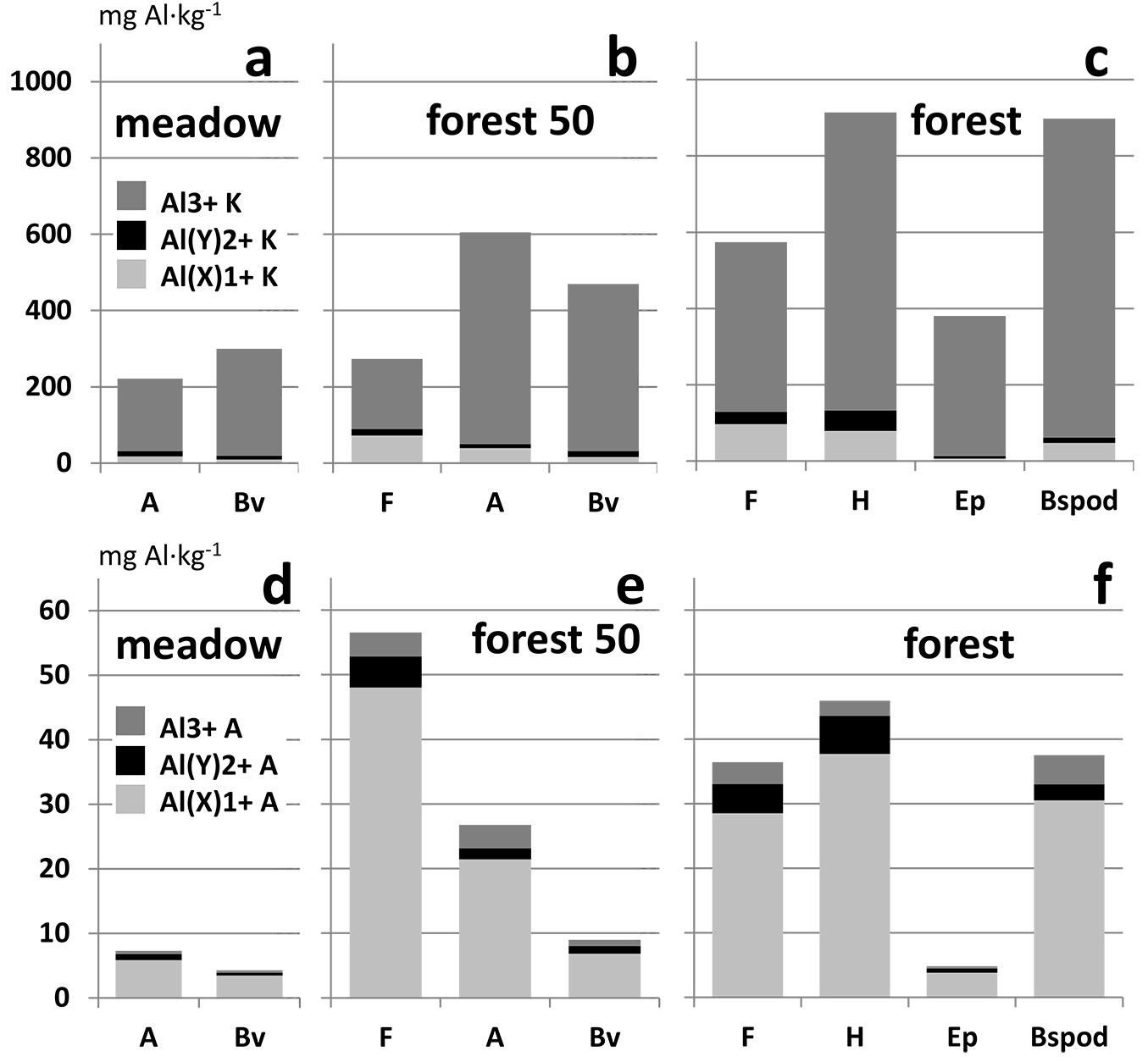

The results of Al fractionation are shown in Fig. 3 and Tab. 2. Concentrations of Al(X)1+ and Al3+ in the A horizon in both extracts are significantly higher for the 50-year-old forest soil than for the meadow. Concentrations of all Al fractions in aqueous extract are higher in the mineral Bv horizon of forest soil than in the meadow. The highest amount of phytotoxic Al3+ in both extracts occurred in the spodic horizons. Concentrations of Al fractions in the KCl extract increased from young to old forest in the F horizon. The opposite trend was observed in the aqueous extract.

Fig. 3 - Distribution of Al fractions (a, b, c: in KCl extract; d, e, f: in aqueous extract) in soil horizons. Average values of samples from meadow. (a, d): scythed meadow in forest vicinity; (b, e): 50-year-old forest planted on former meadow; (c, f): old growth forest.

Forest type change

Tab. 3 shows the values of soil pH in the original beech forest and in the planted spruce forest. A higher pH of surface horizons in the beech forest is evident, in comparison with spruce forest. Statistical differences are presented in Tab. 4.

Tab. 3 - Average values of pHH2O and pHKCl in beech and spruce forest, by soil horizons.

| Soil horizon |

Beech forest | Spruce forest | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pHH2O | pHKCl | pHH2O | pHKCl | |

| F | 4.18 | 3.33 | 3.84 | 2.87 |

| H | 4.14 | 3.5 | 3.78 | 2.96 |

| A | 4.17 | 3.58 | 3.89 | 3.19 |

| B | 4.27 | 3.78 | 4.11 | 3.77 |

Tab. 4 - Differences in the distribution of pH and Al fractions between beech and spruce forests for each soil horizon (results of pair t-test; t-values of the differences).

| Variable | F horizon | H horizon | A horizon | B horizon | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | Prob | t | Prob | t | Prob | t | Prob | |

| pHH2O | 10.97 | <0.001 | 14.24 | <0.001 | 7.67 | <0.001 | 5.30 | <0.001 |

| pHKCl | 17.47 | <0.001 | 23.80 | <0.001 | 9.03 | <0.001 | 1.25 | 0.218 |

| Al(X)1+A | -0.23 | 0.818 | -6.13 | <0.001 | -3.11 | 0.006 | -3.20 | 0.003 |

| Al(Y)2+A | -1.12 | 0.273 | -2.69 | 0.012 | -2.12 | 0.047 | -3.32 | 0.003 |

| Al3+A | 3.12 | 0.004 | 1.29 | 0.207 | -0.83 | 0.417 | -2.50 | 0.018 |

| AlH2O | 1.28 | 0.211 | -3.76 | <0.001 | -2.75 | 0.013 | -4.20 | <0.001 |

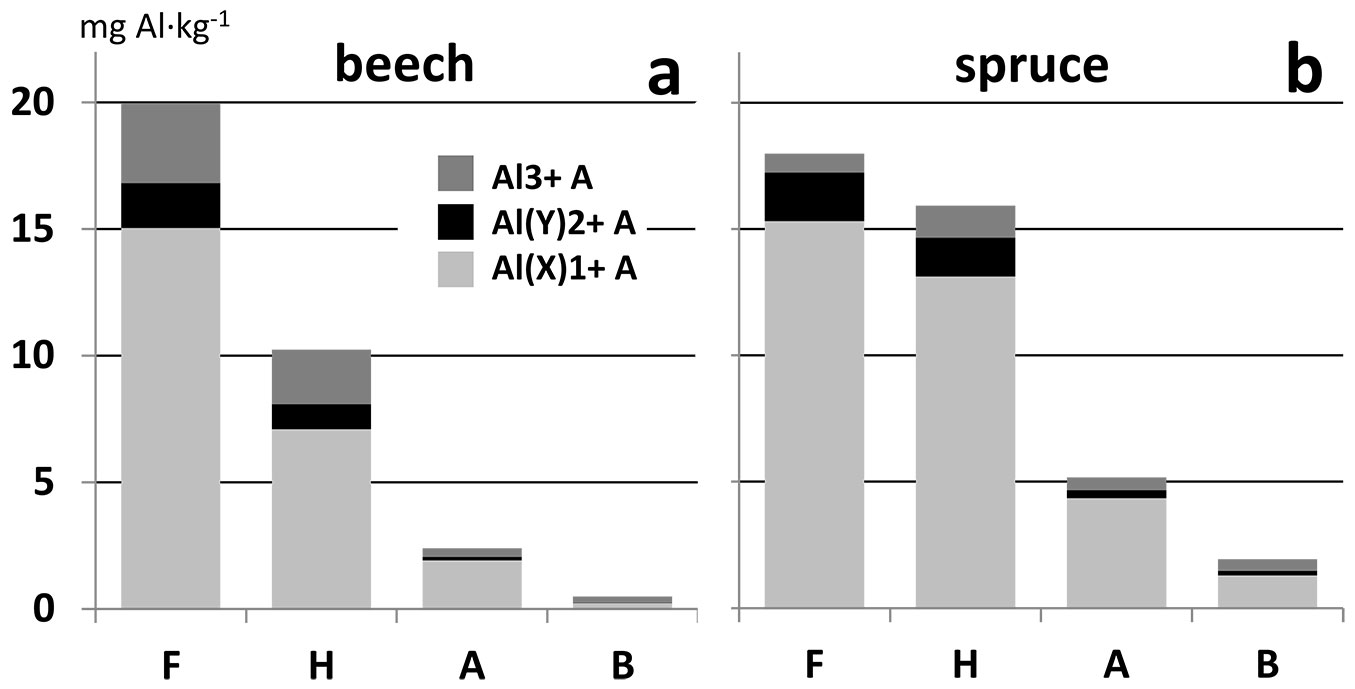

Results of Al fractionation (Fig. 4, Tab. 4) show that the differences between beech and spruce forest soil exist in both organic and mineral horizons. Except for the F horizon, the sum of the Al fractions, and also Al(X)1+ and Al(Y)2+ fractions concentrations, are significantly higher in the spruce forest. The concentration of the Al3+ fraction in the organic F horizon is higher in the beech forest than in the spruce forest.

Fig. 4 - Distribution of Al fractions in aqueous extract in soil horizons. Average values of samples from beech (a) and spruce (b) forest.

Deforestation and amelioration

The basic soil characteristics of long-term deforested area (grass-limed, grass-control) and surviving native forest plots are presented in Tab. 5. Analysis of variance (Tab. S2 in Supplementary material) shows that organic horizons are more affected than mineral horizons by land-use change. Forested soils are more acidic than grass-covered soils. The long-term liming effect resulted in higher CaAR concentrations in the organic horizons of the limed variant. Soil pH was not significantly changed 25 years after liming. Higher differences in soil pH were found between forest and grass-covered (control and limed) plots. Cation exchange capacity was similar for all land uses.

Tab. 5 - Average values of basic soil characteristics in variants (grass-limed, grass-control, native forest) separately for soil horizons.

| Variant | Horizon | pHH2O | pHKCl | MgAR (Mg kg-1) |

CaAR (mg.kg-1) |

ECEC (mmol 100g-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grass limed |

F | 4.33 | 3.57 | 1396 | 2282 | 26.75 |

| H | 4.11 | 3.26 | 813 | 1292 | 22.90 | |

| Ep | 4.05 | 3.32 | 683 | 246 | 7.01 | |

| Bspod | 4.21 | 3.78 | 2794 | 376 | 8.01 | |

| C | 4.51 | 4.23 | 3634 | 429 | 3.34 | |

| Grass control | F | 4.23 | 3.45 | 1034 | 986 | 24.14 |

| H | 4.13 | 3.40 | 861 | 545 | 22.97 | |

| Ep | 4.12 | 3.49 | 1353 | 332 | 7.76 | |

| Bspod | 4.18 | 3.65 | 2692 | 372 | 10.65 | |

| C | 4.44 | 4.19 | 4042 | 470 | 3.44 | |

| Native forest | F | 3.88 | 2.96 | 929 | 1408 | 24.75 |

| H | 3.82 | 2.96 | 523 | 422 | 25.24 | |

| Ep | 3.70 | 3.28 | 1105 | 206 | 7.20 | |

| Bspod | 4.08 | 3.74 | 2895 | 299 | 8.74 | |

| C | 4.29 | 4.18 | 4295 | 447 | 3.84 |

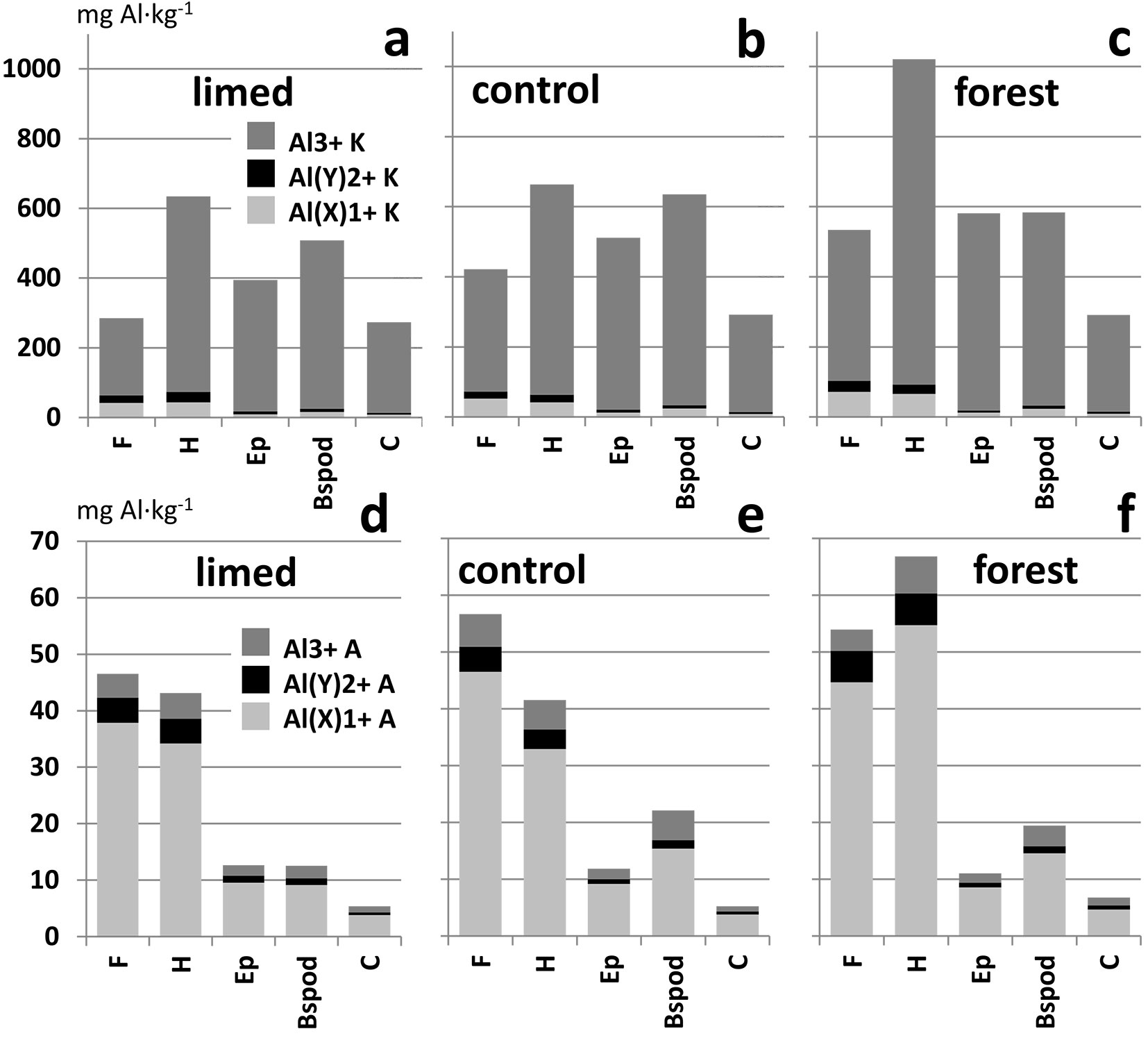

The results of Al fractionation and comparison of vegetation cover variants are shown in Fig. 5 and Tab. S2 (Supplementary material). Analysis of variance for the Al fractions showed that most of the differences occur in the surface organic horizons. These horizons in the surviving forest have the highest concentrations of most of the Al fractions. Almost no difference between the limed and control variant was found. A change of land use influenced the Al(X)1+ and Al(Y)2+ fraction distribution more than that of Al3+.

Fig. 5 - Distribution of Al fractions (a, b, c: in KCl extract; d, e, f: in aqueous extract) in soil horizons. Average values of samples from grass-limed (a, d), grass-control (b, e), and native forest (c, f).

Discussion

Firstly, the differences between Al distributions in the dominant soil types in this mountain area (Fig. 2, Tab. S1) are addressed. Podzol formation is directly controlled by Al transport in the soil profile, from the Ep horizon to spodic type horizons with or without organic matter ([28], [38]). Relative Al depletion of the Ep horizon and relative Al enrichment of the Bspod horizon can be seen in Fig. 2. The high contents of all Al fractions in the surface organic horizons are probably due to the high sorption capacity of organic compounds and long-term accumulation of organic matter, especially in the H horizon ([32]). The cambic Bv horizon is characterized by braunification processes. Fe and Al are released from silicates in situ by this special type of weathering. The Bv horizon is relatively enriched with Al in contrast to substrate (C), but aluminium content is still lower than in the Bspod horizon, which is enriched with Al transported from the upper horizons (Fig. 2, Tab. S1). Different Al distributions in the Podzol and Cambisol soil profiles were also shown by Berggren ([3]) and Maitat et al. ([29]). These differences illustrate the importance of the study sites comparison according to soil horizon.

Afforestation effect

Generally, long-term planting of spruce or other coniferous species leads to enhanced soil acidification and conditions conducive to the podzolization process ([8]). Findings in line with this theory are documented in Tab. 1, which shows that the Podzol soil type was found only in old-growth forest. The increase of soil acidity leads to Al release in its mobile forms ([40], [34]). The results in Fig. 3 and Tab. 2 confirm that the afforestation of meadow leads to the release of monovalent and trivalent Al fractions, especially in the A horizon. A similar situation was documented by Adams et al. ([1]) in New Zealand.

The concentration of monovalent and divalent Al fractions in the KCl extract increased significantly from young to old forest in the F horizon (Fig. 3, Tab. 2). This agrees with the soil pH decrease and cation exchange capacity increase ([15] - Tab. 1, Tab. 2). The opposite trend was seen in the aqueous extract. The concentration of the monovalent Al fraction decreased from young to old forest in the F horizon. This result may be explained by the difference between the aggrading humus layers of young forest and the mature humus layers of old forests. It has been suggested that leaf litter quality varies with tree age and has a huge impact on humus development ([21], [11]). Ponge et al. ([37]) suggested that a higher uptake of nutrients by trees during their phase of intense growth may lead to lower soil nutrient availability and decomposer activities. The decrease in biological activity may lead to lower litter decay rates, promoting the accumulation of organic materials ([43]). The aggrading humus layers of young forest have lower cation exchange capacity and do not bind Al as much as the mature humus layers in old forests.

Other authors ([14]) found a huge difference in the relative distribution of Al fractions in KCl extracts between spruce and meadow. This was not confirmed in the present study.

Forest type change

Better soil conditions (pH, nutrient concentrations) of beech than spruce forest have been reported by several authors ([30], [32]). The organic horizons of Norway spruce forest were found to be more acidic than those of beech forest (Tab. 3, Tab. 4). It could be supposed that higher concentrations of Al fractions will be found in spruce forest. The indirect relationship between the concentration of mobile Al forms and soil reaction is well known ([40], [34]). However, the results in Fig. 4 and Tab. 4 confirm this only partially. In the case of the F horizon and Al3+ fraction, the opposite trend was found. Tejnecký et al. ([42]) showed higher dissolved organic carbon (DOC) content in spruce forest surface horizons than in beech forest. DOC is a significant ligand for Al complexation ([45]). These two facts have opposing effects on Al3+ concentration ([27]). It is probable that the DOC effect plays a more important role than soil pH. Therefore, Al complexation with DOC would decrease Al3+ concentration in spruce more than it would in beech forest soils.

Deforestation and amelioration

Analysis of variance (Fig. 5, Tab. S2) for Al fractions showed that most of the differences occur in the surface organic horizons. Twenty-five years after limestone application, the difference between grass-limed and grass-control was not found. This result is not in contradiction with the decrease of Al concentration related to the short-time liming effect ([44], [6] [20]). In contrast, both of these grass variants often have lower concentrations of Al fractions in comparison with native forest. Therefore, grass expansion could be considered as a natural regeneration mechanism of acidified soils. However, the toxic effect of aluminium, represented by Al3+ concentration in aqueous extract, is similar in all variants. Only the potential (KCl extract) risk of Al toxicity was higher in the native forest variant.

Conclusion

Vegetation cover change can influence the concentration of Al fractions, mainly in surface organic horizons. Differences were found to be more common in the KCl extracts and for Al(X)1+ and Al(X)2+ fractions than in aqueous extracts and the Al3+ fraction, respectively. Afforestation increased the concentration of AlKCl and AlH2O. An increase of Al fraction concentrations in the KCl extract from younger to older forests was observed in the F horizon. The opposite trend occurred in the aqueous extract. This could be explained by the fact that while forming the humus layer, Al is not bound as strongly as in the mature humus layer of old-growth spruce forests. Where natural beech forest was replaced by spruce, the concentration of AlH2O increased, but concentration of Al3+ decreased in the F horizon. This seems to confirm that organic compounds in the soils of spruce forest can transform this toxic fraction. In contrast, grass expansion after deforestation led to a significant decrease in the concentrations of AlKCl and AlH2O. Acid soil liming increased the Ca concentration, but their long-term effects on soil pH and the concentrations of potentially toxic Al fractions were not apparent. With respect to the distribution of the most toxic Al fraction (Al3+ in aqueous extract), no significant long-term effect of deforestation and liming was observed.

These results could be used in the management of forested areas endangered by soil acidification. Limestone application can be recommended for younger forests preferentially, where Al toxicity is probable, or for utilization of natural mechanisms in damaged forest recovery.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Ondrej Drabek

Sarka Stejskalova

Vaclav Tejnecky

Monika Hradilova

Antonin Nikodem

Lubos Boruvka

The Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Department of Soil Science and Soil Protection, Kamýcká 129, 165 00 Prague Suchdol (Czech Republic)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Pavlu L, Drabek O, Stejskalova S, Tejnecky V, Hradilova M, Nikodem A, Boruvka L (2018). Distribution of aluminium fractions in acid forest soils: influence of vegetation changes. iForest 11: 721-727. - doi: 10.3832/ifor2498-011

Academic Editor

Giustino Tonon

Paper history

Received: May 23, 2017

Accepted: Aug 27, 2018

First online: Nov 06, 2018

Publication Date: Dec 31, 2018

Publication Time: 2.37 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2018

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 45583

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 38863

Abstract Page Views: 3074

PDF Downloads: 2760

Citation/Reference Downloads: 12

XML Downloads: 874

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 2649

Overall contacts: 45583

Avg. contacts per week: 120.45

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2018): 7

Average cites per year: 0.88

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Impact of deforestation on the soil physical and chemical attributes, and humic fraction of organic matter in dry environments in Brazil

vol. 15, pp. 465-475 (online: 18 November 2022)

Research Articles

Carbon storage and soil property changes following afforestation in mountain ecosystems of the Western Rhodopes, Bulgaria

vol. 9, pp. 626-634 (online: 06 May 2016)

Research Articles

Effects on soil characteristics by different management regimes with root sucker generated hybrid aspen (Populus tremula L. × P. tremuloides Michx.) on abandoned agricultural land

vol. 11, pp. 619-627 (online: 04 October 2018)

Short Communications

Variation in soil carbon stock and nutrient content in sand dunes after afforestation by Prosopis juliflora in the Khuzestan province (Iran)

vol. 10, pp. 585-589 (online: 08 May 2017)

Research Articles

Changes in the properties of grassland soils as a result of afforestation

vol. 11, pp. 600-608 (online: 25 September 2018)

Research Articles

Soil stoichiometry modulates effects of shrub encroachment on soil carbon concentration and stock in a subalpine grassland

vol. 13, pp. 65-72 (online: 07 February 2020)

Research Articles

Soil fauna communities and microbial activities response to litter and soil properties under degraded and restored forests of Hyrcania

vol. 14, pp. 490-498 (online: 11 November 2021)

Research Articles

Wood-soil interactions in soil bioengineering slope stabilization works

vol. 2, pp. 187-191 (online: 15 October 2009)

Research Articles

Soil respiration along an altitudinal gradient in a subalpine secondary forest in China

vol. 8, pp. 526-532 (online: 01 December 2014)

Research Articles

The manipulation of aboveground litter input affects soil CO2 efflux in a subtropical liquidambar forest in China

vol. 12, pp. 181-186 (online: 10 April 2019)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword