Individual-based approach as a useful tool to disentangle the relative importance of tree age, size and inter-tree competition in dendroclimatic studies

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 8, Issue 2, Pages 187-194 (2015)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1249-007

Published: Aug 21, 2014 - Copyright © 2015 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

In this work, an individual-based approach was used to assess the relative importance of tree age, size, and competition in modulating the individual dendroclimatic response of Quercus robur L. This was performed in a multi-aged forest in northwestern Spain under a wet Atlantic climate. All trees in five replicated forest stands with homogeneous soil conditions were mapped and inter-tree competition was quantified with a distance-dependent competition index. Tree rings of cored trees were crossdated and total age was estimated on individuals where the pith was missed. The climatic response was evaluated by bootstrapped correlations of individual tree-ring chronologies with climatic records. Inter-annual growth variation, i.e., mean sensitivity, was independent of tree age and bole diameter, but modulated by competition. Water excess in previous summer-autumn and spring negatively affected growth, while warmer September conditions favored growth. Individual response to climate was independent of tree age, but related to the joint effect of tree bole diameter and competition. Larger oaks in less competitive environments responded more plastically to climatic stress, while smaller trees under high competition levels were less responsive to climate. Strong inter-tree competition reduced growth plasticity but amplified the vulnerability of smaller oaks to the particularly rainy conditions of the study area. These findings suggest that inter-tree competition is a relevant size-mediated extrinsic factor that can potentially modulate individual radial growth variation and its response to limiting climatic conditions in temperate deciduous forests. This study highlights the value of individual-based approach as a useful tool that informs about the relative contribution of factors modulating the climatic response of tree-ring growth.

Keywords

Climate-Growth Response, Competitive Effect, Dendroecology, Individual Variation, Quercus robur, Size Effect, Tree Age

Introduction

There is an ongoing debate on the potential role of intrinsic tree traits, such as age and size, in modulating the response of radial growth to climate. An earlier study demonstrated that the individual response of Picea glauca (Moench) Voss. radial growth to summer temperature may be age dependent, and that this dependence may be modulated by local site hydrology ([47]). Further investigations revealed that lower temperatures near the alpine timberline can be more limiting for growth of old than young conifer trees ([5], [53]). Furthermore, older deciduous oaks were shown to be more responsive to water availability than younger ones under temperate climate conditions ([43], [10]). Recent studies with Mediterranean conifers established that younger trees, with a poorly developed root system and a longer growing season, were more sensitive to drought than older trees ([44], [51]). Therefore, age-modulated radial growth response to climate has been suggested as a widespread phenomenon that can involve different tree species growing under diverse environmental conditions ([47], [5]). Even if tree-ring series used for climate reconstructions are generally taken from oldest trees growing in limiting environments, age-related changes in the climatic signal could potentially affect the interpretation of dendroclimatic reconstructions ([16]).

Tree size is also known to potentially modulate the climatic sensitivity of radial growth ([31], [13], [34]), because a number of essential physiological processes including soil nutrient uptake, xylem water flux, photosynthetic rates, and movement of growth hormones are all strongly mediated by size ([38], [33], [41], [48]). At water-limited sites, smaller trees demonstrate greater sensitivity to summer drought ([13], [29]); however, at sites where water is less limiting, larger trees have the highest sensitivity to drought ([39], [34]). Concurrently with the inherent link between tree age and size, all this evidence suggests that species-specific physiological and/or morphological shifts during tree ontogeny, combined with site-specific limiting environmental conditions, can lead to age- or size-induced growth responses to climate.

Physiological studies assessing the effects of age and size on tree vigor concluded that extrinsic factors mediated by size, such as decreased soil nutrient availability or asymmetric inter-tree competition, could be even more important than age or size in modulating tree reaction to stresses ([12], [33]). Competition among neighboring trees is an extrinsic stressor that greatly influences water and nutrient uptake, light interception, carbon assimilation, and ultimately determines tree vitality and survival in dense temperate forests ([36], [21]). Inter-tree competition can also potentially modulate the biological response of trees to long-term climate variation ([39], [29], [32]). Despite considerable effort being devoted to understand both age- and size-modulated radial growth responses to climate, little research has been undertaken regarding the importance of competition in modulating the dendroclimatic response at stand level ([26], [20], [6]). However, no research has been undertaken to date regarding this topic at individual level.

In this paper, I use an individual-based approach to assess the relative importance of tree age, size, and inter-tree competition on the individual response of radial growth to climate in a multi-aged pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.) forest under Atlantic climate conditions in the Serra do Suido mountain range, northwestern Spain. The specific aims of this study were to quantify the relationships between tree age, size, and competition intensity in a multi-aged pedunculate oak forest, to evaluate the individual variability in radial growth responses to climate under wet Atlantic conditions, and to determine the relative contribution of tree age, size, and inter-tree competition in modulating individual radial growth variation and its response to limiting climatic conditions.

Material and methods

Study area

The Serra do Suido is a mountain range with a maximum elevation of 1151 m in the Pontevedra province, Galicia, north-west Spain. Upland heath dominates on the deforested slopes while oak woodlands are found on valley bottoms. The dominant woodland is an Ibero-Atlantic acidophilous oak forest (G1.8/P-41.56, EUNIS habitat classification) almost exclusively composed of pedunculate oak, with a sparse understorey of Ilex aquifolium L., Pyrus cordata Desv., and Crataegus monogyna Jacq.

Soils are acidic, nutrient-poor Lithic and Umbric Leptosols and Epileptic Umbrisols on granite bedrock ([3]). Climate is temperate and humid, with a mean annual temperature of 12.0 °C, and a mean annual precipitation of 1315 mm for 1901-2006. Total annual precipitation in the study area significantly increased throughout the 20th century, and particularly rainy conditions were recorded in 2001, with 2163 mm in total annual precipitation. Seasonal water excess in recent decades, and particularly the extremely rainy conditions in 2001, caused oak decline in this forest ([45]).

Sampling and soil traits assessment

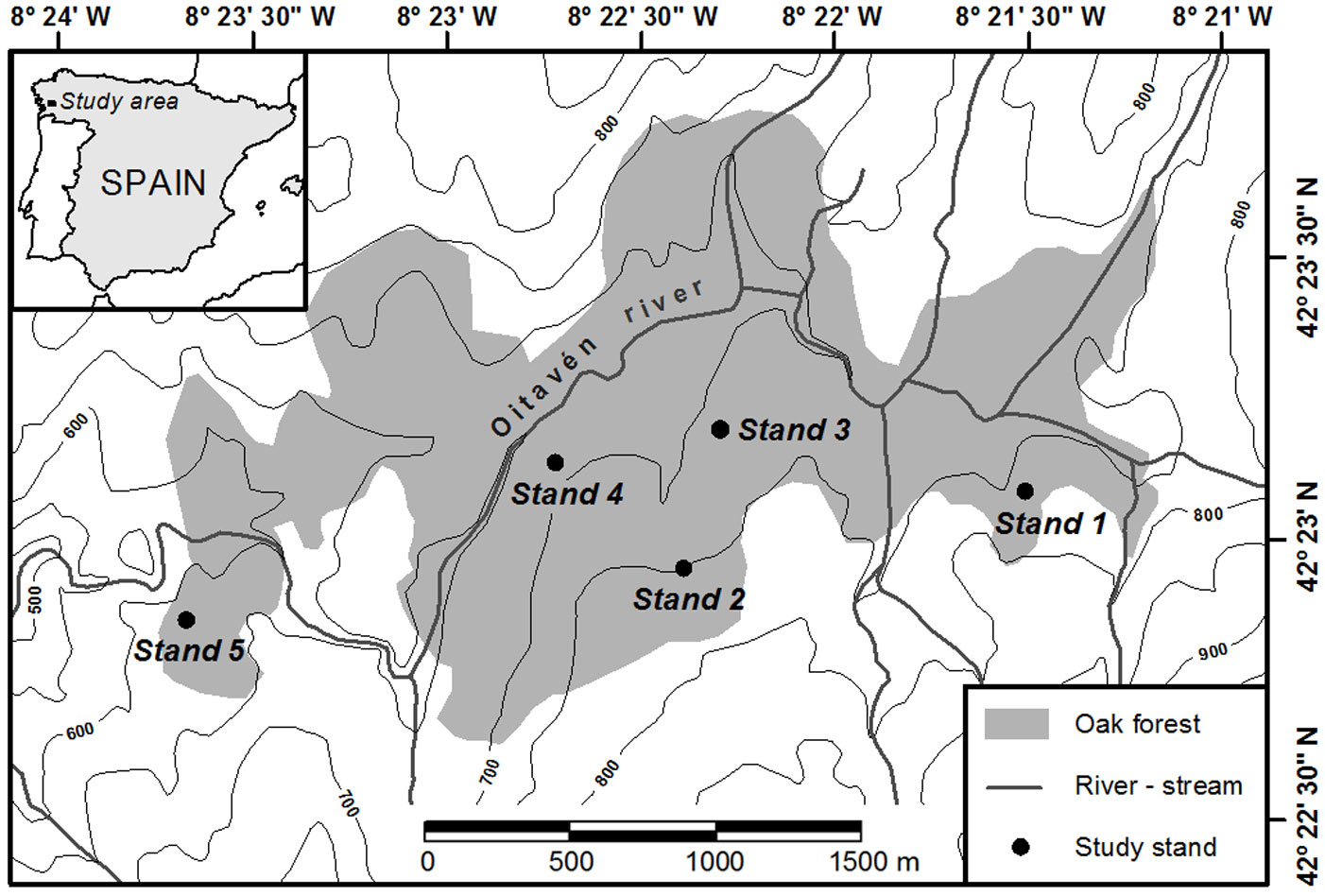

A 385-ha wooded section on the windward side of the Serra do Suido was selected for study (42° 22′ 40″ - 42° 23′ 50″ N, 08° 21′ 10″ - 08° 23′ 45″ W; Fig. 1). A replicated sampling was performed in five representative forest stands located at elevations between 610-770 m a.s.l., mainly facing north and with mean slopes of 25-30% (Tab. 1). Total tree density in these stands varied between 305 and 455 trees ha-1, and total basal area between 28.5 and 35.1 m2 ha-1. In 2007, a rectangular study plot of 60 × 70 m was randomly established within each stand, and all oaks found within the plots were mapped with a laser total station (Pentax® R-325 NX). All trees were tagged and their DBH (stem diameter at 1.3 m above the ground) was measured. Thirty trees with DBH > 10 cm were randomly selected within an inner rectangle of 40 × 50 m centered inside each study plot for wood core sampling. Two wood cores were collected along opposing radii oriented parallel to the slope contour line from each of the thirty selected trees per plot, using increment borers at breast height.

Fig. 1 - Location of the study area in north-western Spain, and of the five study stands within the multi-aged oak forest. Contour lines indicate 50 m elevation intervals.

Tab. 1 - Traits of study stands and sampled trees in the Serra do Suido range, north-western Spain. (DBH): tree bole diameter at 1.30 m above ground; (Soil texture): soil proportion with size < 2 mm; (OM): organic matter content; (a): Mean ± SD.

| Traits | Stand 1 | Stand 2 | Stand 3 | Stand 4 | Stand 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation (m) | 770 | 750 | 720 | 690 | 610 |

| Aspect | N | NE | NW | N-NE | N-NW |

| Slope (%) | 26 | 27 | 25 | 30 | 28 |

| Total tree density (ha-1) | 305 | 360 | 440 | 430 | 455 |

| Total basal area (m2 ha-1) | 35.1 | 28.5 | 27.3 | 32.0 | 28.5 |

| Tree age (yr) a | 162 ± 18 | 105 ± 42 | 102 ± 12 | 102 ± 27 | 120 ± 23 |

| DBH (cm) a | 38.0 ± 7.5 | 28.5 ± 9.2 | 28.8 ± 7.3 | 31.5 ± 8.0 | 28.2 ± 6.6 |

| Competition index a | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 2.1 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 2.2 | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 2.3 ± 1.5 |

| Soil texture (%) a | 74.1 ± 6.9 | 74.8 ± 4.7 | 79.8 ± 5.3 | 72.8 ± 6.2 | 68.1 ± 8.1 |

| Soil OM (%) a | 22.6 ± 2.9 | 23.8 ± 2.6 | 20.9 ± 4.4 | 20.6 ± 4.2 | 20.5 ± 5.6 |

| Soil pH (H2O) a | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.3 |

Additionally, in order to assess the variability of soil traits, three soil samples comprising the first 10 cm of soil were randomly taken at 1.5 m from the stem base around fifteen randomly selected trees per stand with a 5-cm diameter soil core sampler, which were pooled into a single composite soil sample per tree. Soil samples were sieved at 2 mm and air-dried, organic matter content was determined by combustion (500 °C, 4 h), and soil pH measured with a glass electrode in distilled water solution (water:soil, 1:2.5).

Inter-tree competition assessment

Inter-tree competition was quantified on the thirty selected trees per plot with a distance-dependent competition index (CI). Basal area (BA, cm2) of each tree was computed from its geometrical radius, and competition intensity was quantified as ([30] - eqn. 1):

where BAi is the basal area of subject tree i, BAj is the basal area of competitor tree j within the search radius R, and Dij is the distance (m) between subject tree i and competitor tree j. Competitors are defined as those oaks with DBH > 10 cm included inside a prescribed search radius R equal to 8 m from the subject tree, which is coherent with that previously used in other studies ([39], [29]). The CI varies as a direct function of the relative size of competitors in comparison to the subject tree, and an inverse function of the distances between competitors and the subject tree.

Dendrochronological procedures

The cores were processed and tree-ring series were visually dated by matching the patterns of narrow and wide rings ([52]). In cores where the pith was missed, tree age at coring height was estimated with a mean absolute error of ± 4 yrs, according to a method based on the convergence of xylem rays at the pith to estimate the length of the missing radius, and on an empirical model of initial radial growth to estimate the number of missing rings ([42]). Series of total tree-ring width were measured on each core to the nearest 0.001 mm with a sliding-stage micrometer (Velmex Inc., Bloomfield NY, USA) interfaced with a computer. The software package COFECHA ([23]) was used to quantitatively check for crossdating.

Every raw ring-width series was standardized using the ARSTAN program ([9]). The series were fitted to a spline function with a 50% frequency response of 32 yrs, which was flexible enough to minimize the non-climatic variance and maximize the high-frequency climatic signal ([24]). The residuals obtained were pre-whitened by autoregressive modeling, giving dimensionless indexes that represent independent, normalized, and homogenized records of annual growth. The year-by-year arithmetic mean of the two series of standardized and pre-whitened tree-ring indexes from each tree, for the period held in common by both cores of the tree, was calculated to obtain an individual chronology. Inter-annual variability of individual tree-ring chronologies, prior to pre-whitening, was assessed using the standard statistic mean sensitivity (MS) that describes the mean percentage change from each growth index to the next ([2]).

Climate data

The climate data used in this study were monthly gridded time series for total precipitation (Prec), mean minimum (Tmin) and maximum (Tmax) temperature, and Palmer drought severity index (PDSI), obtained from the Climate Explorer of the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (⇒ http:// climexp.knmi.nl/), for the 0.5° longitude × 0.5° latitude sector in which the study area is located. Series for Prec, Tmin and Tmax were obtained from the CRU TS 3 data set, period 1901-2006, while series for PDSI were obtained from the CRU self-calibrating PDSI data set, period 1901-2002. The PDSI combines air temperature, cumulative rainfall, and field water-holding capacity to give a standardized measure of soil water content ([11]). Monthly time series of water balance (WB) were also calculated as ([50] - eqn. 2):

where Prec is the total precipitation and PET is the potential evapotranspiration, estimated as a function of monthly mean temperature and geographical latitude, accor-ding to the standard Thornthwaite’s method ([50]). Monthly data from May of the previous year (May(-1)) to October of the current growth year (Oct) were used, since this period includes both previous and current growing seasons in Q. robur ([22]). Monthly data was also averaged (Tmin, Tmax, PDSI) or summed (Prec, WB) in periods of three months to identify their main effects on individual radial growth at both monthly and seasonal scales.

Climate sensitivity assessment

The monthly or seasonal climatic variables that significantly influenced radial growth were identified by means of the percentage of trees that showed significant correlations with climate in 1971-2000, the most recent 30-yrs period common to all individual tree-ring chronologies prior to 2001, which was the wettest year on record for the site ([45]). Individual climatic responses were calculated as bootstrapped correlations of the monthly and seasonal climatic time series with individual tree-ring chronologies. Bootstrapped correlations and their statistical significance were computed with the software DFOESPCMJN2002 ([1]). Most significant relations were revealed by the highest percentages of trees showing significant individual correlations with climate.

Dependence of individual climatic response on tree traits and competition

To explore the influence of tree age, size, and inter-tree competition on recent individual climatic response, the relationships between such factors and the previously calculated correlations of individual tree-ring chronologies with climatic variables were assessed. Since it has been previously established that tree bole diameter and crown dimensions, such as height and width, are strongly related in Quercus robur ([25], [8]), in this work I used DBH as a suitable indicator of total tree size.

According to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality, individual MS and correlation values with climate were not normally distributed. These data were normalized with the Fisher’s transformation z ([18]), also called the inverse hyperbolic tangent transformation, which allows the application of regression techniques on normally distributed correlations ([17] - eqn. 3):

where r represents the individual correlation of radial growth with climate or the chronology statistic MS. The proportion of significant individual correlations was calculated for every significant climatic variable affecting individual radial growth. The relationships of tree age, DBH, and CI with normalized MS were explored with correlation analysis.

Multiple linear regressions were used to study the relationships of tree age, DBH, and CI with the normalized correlations of radial growth with climate. Based on the adjusted coefficients of determination from multiple regressions, a variation partitioning was additionally performed ([28]) that provided the relative importance of each significant predictor (tree age, DBH, CI) separately, and their joint effects, in modulating individual responses to climate. According to this procedure, the pure and joint effects of age, DBH and CI were calculated, and transformed in a percentage of the total variation of the climatic response explained by every variable.

Results

Soils in the study stands were relatively homogeneous. Between 68.1-79.8% of soil material showed a size < 2 mm, with a high content of organic matter ranging between 20.5-23.8%, while soil pH was very similar in all the study stands, ranging between 3.6-3.9 (Tab. 1). Tree age at breast height ranged between 51 and 203 yrs, DBH between 13 and 57 cm, and CI between 0.15 and 8.58. Mean CI in the study stands varied between 1.4 and 2.5 (Tab. 1).

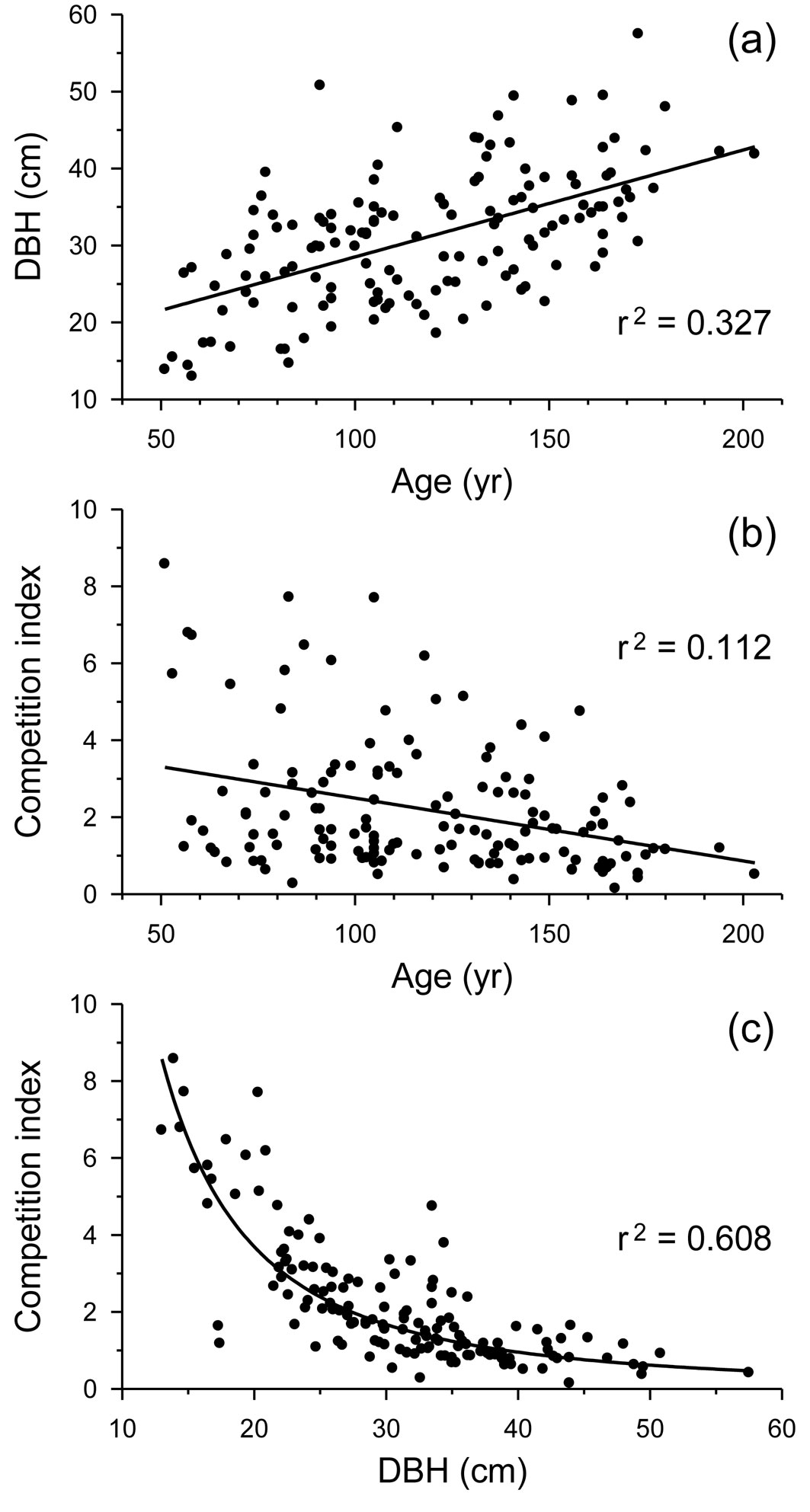

Age at breast height and size were positively related and shared 32.7% of their variance (Fig. 2a). Age and competition shared only 11.2% of their variance and showed an opposite relationship (Fig. 2b). However, size and competition shared 60.8% of their variance according to a power fit, with higher competition intensities for smaller trees (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2 - Relationships between (a) tree age at breast height and DBH, (b) tree age at breast height and competition index, and (c) DBH and competition in Q. robur trees from all study stands together. Linear or power fits and their coefficients of determination (r2), all of them highly significant (p < 0.001), are shown.

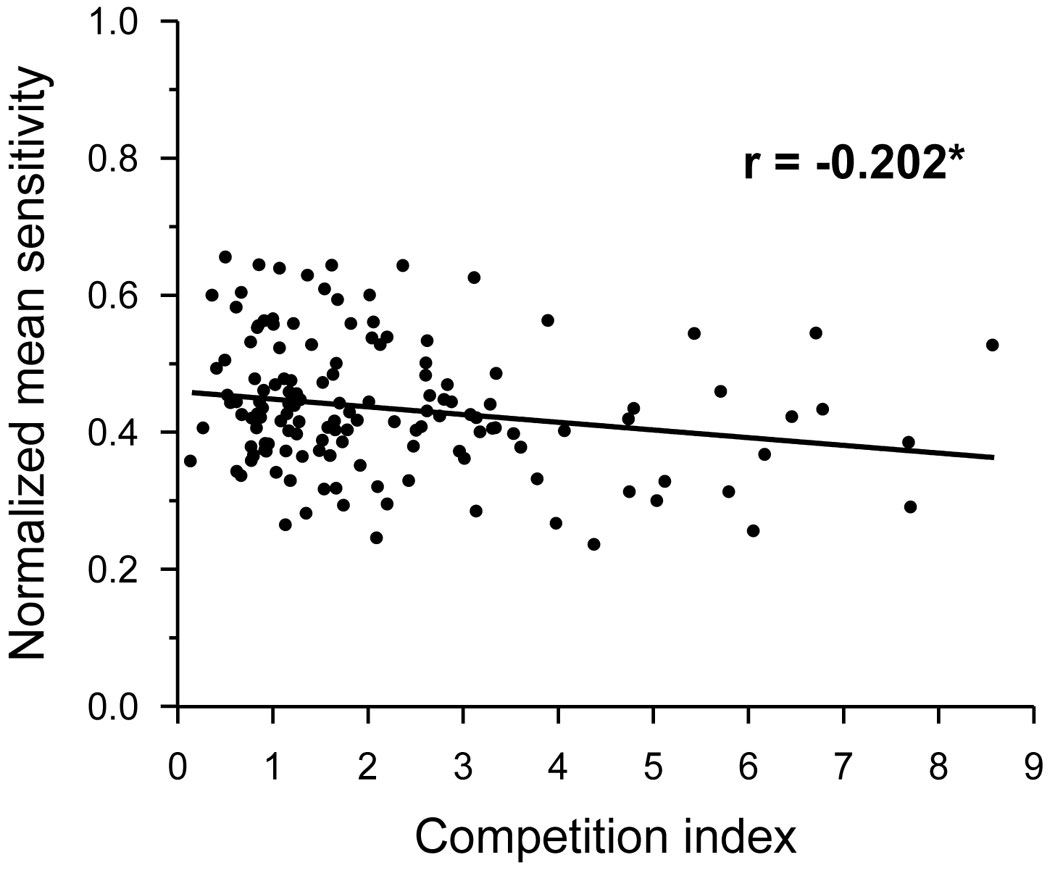

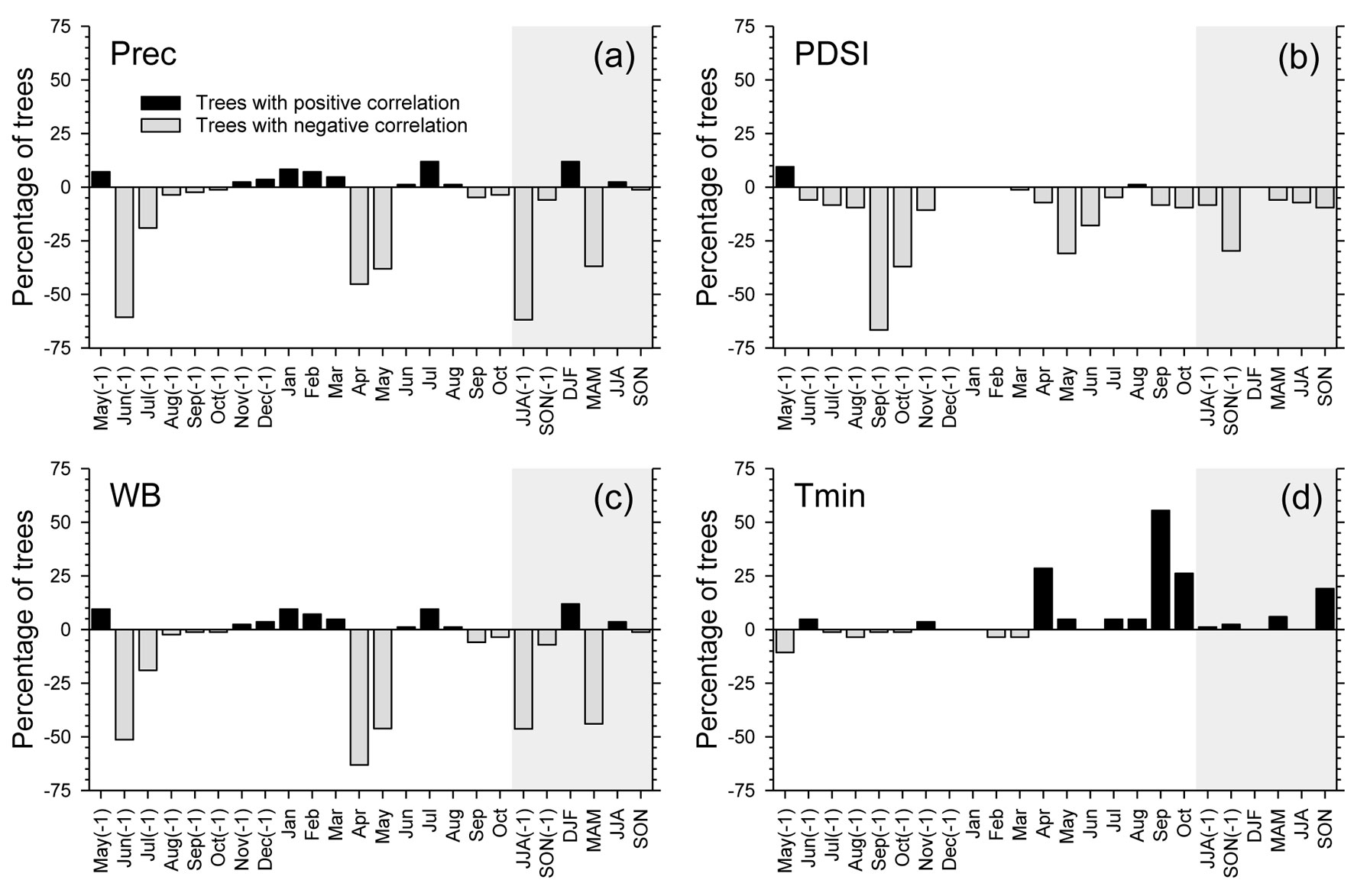

The MS was independent of tree age and DBH (p > 0.05), but was significantly related to CI, which showed a negative correlation with MS (Fig. 3). The proportion of trees with significant individual correlations with climate revealed a negative response of oak growth to previous June-August precipitation (Fig. 4a), to previous September-October PDSI (Fig. 4b), and to April-May water balance (Fig. 4c). However, a high proportion of trees showed a positive relationship between minimum temperature in current September and oak growth (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 3 - Relationships of the normalized mean sensitivity from individual radial growth chronologies, with the competition index in Q. robur trees from all study stands together. Linear fit, correlation coefficient (r), and its statistical significance are shown. (*): p < 0.05.

Fig. 4 - Percentage of trees showing significant correlations with climate for monthly and seasonal precipitation (a), Palmer drought severity index (b), water balance (c), and minimum temperature (d), in the period 1971-2000. Positive and negative percentages refer to positive and negative correlations, respectively. Shaded areas correspond to correlations with seasonal climatic variables.

Individual climatic response of oaks was independent of tree age (p > 0.05), while DBH and CI showed significant linear relationships with individual response of oaks to all selected climatic factors (Fig. 5). Individual response to previous summer precipitation, previous autumn soil water content, and spring water balance were negatively correlated with DBH and positively correlated with CI. By contrast, individual response to September minimum temperature was positively correlated with DBH and negatively so with CI. More negative individual responses to water availability and positive to September minimum temperature were noticed for larger trees and trees under lower competition intensity.

Fig. 5 - Relationships of the normalized bootstrapped correlations of radial growth with climate, with tree age, size (DBH), and competition index (CI) in Q. robur trees from all study stands together. Statistically significant (p < 0.05) and non-significant bootstrapped correlations are differentiated by solid and empty dots, respectively. Linear fits, correlation coefficients (r), and their statistical significances are shown. (*): p < 0.05; (**): p < 0.01; (***): p < 0.001.

Linear regressions showed that between 3.5-11.1% of the individual climatic response was related to DBH variation, between 4.1-12.7% was related to CI variation, and between 3.9-13.3% was related to the combination of DBH and CI, all of them statistically significant (Tab. 2). The variation partitioning indicated that the greatest proportion of this variation (3.7-10.5%) was related to the joint effect of DBH and CI, followed by the sole effect of CI that was considerably lower (0.4-2.5%). The individual effect of DBH was also reduced, and even negative, which indicates that DBH explains less variation than would be the case for random normal variables in the cases of Apr-May WB and Sep Tmin ([28]).

Tab. 2 - Adjusted coefficients of determination (r2adj) and p values of linear regression models for DBH, CI, and both DBH and CI (DBH + CI) modulating individual climatic responses (normalized bootstrapped correlations with climate time series) of tree-ring widths in 1971-2000. The fractions of variance of every climatic response explained by DBH alone, by the combination of DBH and CI, and by CI alone, are shown. (Prec): precipitation; (PDSI): Palmer drought severity index; (WB): water balance; (Tmin): mean minimum temperature; (a): pure effect of DBH; (b): joint effect of DBH and CI; (c) pure effect of CI, calculated according to Legendre ([28]).

| Climatic response |

DBH | CI | DBH + CI | Fraction of variance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r 2 adj | p | r 2 adj | p | r 2 adj | p | a | b | c | |

Jun-Aug(-1) Prec |

0.111 | <0.001 | 0.127 | <0.001 | 0.133 | <0.001 | 0.006 | 0.105 | 0.022 |

Sep-Oct(-1) PDSI |

0.079 | <0.001 | 0.079 | <0.001 | 0.086 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.072 | 0.007 |

Apr-May WB |

0.062 | 0.004 | 0.091 | <0.001 | 0.087 | 0.001 | -0.004 | 0.066 | 0.025 |

Sep Tmin |

0.035 | 0.014 | 0.041 | 0.008 | 0.039 | 0.023 | -0.002 | 0.037 | 0.004 |

Discussion

This study demonstrates that individual radial growth response to seasonal water excess and autumn temperature was independent of tree age in this multi-aged oak forest, but was modulated by the joint effect of tree size and inter-tree competition. This finding disagrees with previous studies on temperate deciduous oaks including Q. robur, Q. alba L., and Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl., in which older trees showed a greater sensitivity to water availability than younger ones ([43], [10]), and different size classes showed a similar radial growth response to climate ([34], [54]). The straightforward relationship between tree size and age indicated that size increment was strongly associated with aging, a fact which complicates our understanding of whether changes in growth efficiency and vitality are a function of increasing age or size ([33]). Intrinsic age-dependent developmental shifts should be specifically related to cellular senescence, alterations of gene expression, or changing patterns of organ differentiation and function faced by trees as they become older ([12]). However, it has been argued that age effects on the response to stresses may be more related to increasing size, or to the influence of size-mediated extrinsic factors, than on tree aging alone ([12], [38], [33]). The findings of this study supported this interpretation, by showing that the joint effect of inter-tree competition and DBH significantly modulated the individual sensitivity to climate under relatively homogeneous soil conditions. The absence of age-related changes in the climatic signal may imply that, in this particular case, tree age would not affect the interpretation of potential dendroclimatic reconstructions based on oak tree-ring series.

Since DBH and crown size are strongly interrelated in Quercus robur ([25], [8]), and the associated error of DBH measurements is normally considerably lower in comparison to height measurements, the individual DBH has been used as a surrogate for total tree size. Inter-tree competition and tree DBH were strongly related in this case study, in all likelihood because dominant trees in less competitive environments had a greater capacity than suppressed trees to grow and become larger ([37]). Tree size modulates the direction and intensity of the competitive interaction, since large trees generally had greater capacity to intercept solar radiation, acquire resources, and respond to stresses than small individuals ([49], [35]). High competition levels reduced oak inter-annual growth variation (MS), which is coherent with a less plastic growth and a weak climatic response of smaller trees in more competitive environments ([31], [46]). The finding that larger trees growing under lower competition levels were the most responsive to climate supports previous studies that compared climatic signal in tree-ring chronologies of sub-populations stratified by size or competition ([39], [34], [54]). The obtained findings were also supported by investigations on competition effects on tree response to climate at stand level ([26], [20], [6]), which showed that competition can reduce, or mask, the climatic signal. In this case study, however, the effects of competition on dendroclimatic response occurs at individual level, but not at stand level. When radial growth of sampled individuals was averaged into a mean stand tree-ring chronology, there is no relationship between the climatic response of mean stand chronology and stand tree density or basal area (results not shown).

A previous study in this forest showed that oaks that died, as a consequence of the extremely rainy conditions in the year 2001, were smaller and had lived under higher competition levels than surviving oaks ([45]). This evidence supports the theory that competition can predispose trees to the damaging effects of a climatic stress ([29]). Strongest competition usually occurs at the stem exclusion phase, where regular tree death is related to a set of individual traits such as small size, non-dominant position in the canopy, and decreasing growth trend ([37], [36]). It has been recently established that inter-tree competition is an important regulator of individual tree growth in diverse types of Iberian forests, causing much larger reductions in potential growth than would be caused by tree size or climate ([21]). In addition, a recent dendroecological study on Juniperus thurifera L. in north-central Spain revealed that interference from neighboring trees can be more influential than local environmental heterogeneity in modulating the individual response to climate ([46]). These previous findings, together with the evidences obtained from this study, indicate that inter-tree competition should be considered as a relevant size-mediated extrinsic factor that can potentially modulate individual radial growth variation and its response to climate.

The detrimental impact of water excess on radial growth found in this study disagrees with previous dendroclimatological studies on deciduous oaks. Drought in the active growing season is the climatic stress most frequently evidenced as limiting growth of pedunculate oak in northern, central, and southern Europe ([43], [15], [19], [14]). In this case, however, the study area is on a windward slope that directly intercepts wet westerly fronts from the Atlantic Ocean on relatively homogeneous soils. Persistent soil water excess has been recorded since the 1960s, with extremely rainy conditions in 2001, which induced a detrimental impact on oak growth ([45]).

In addition, warm September conditions probably delayed the end of cambial activity and extended the active growing period, leading to the formation of wider rings. A recent study on cambial dynamics and phenology of Q. robur in northwest Spain showed that latewood formation usually ends in mid-September, but further differentiation of latewood cells can continue for at least two more weeks when September temperature is elevated ([22]). Rising temperatures generally have a positive effect on growth of Iberian broadleaved tree species, particularly of deciduous Atlantic trees ([21]). A positive effect of September temperature on the growth of trees under lower competition levels is consistent with the higher rates of cambial activity and the longer growing season found in dominant trees compared to suppressed ones ([40]). The recent extension of the active growing season observed in many tree species throughout Europe, linked to global climate warming ([7], [27]), probably exacerbated the positive impact of September temperature on oak radial growth.

Conclusions

This study emphasizes the usefulness of an individual-based approach to study the potential modulation of growth responses to climate by intrinsic tree traits and extrinsic factors quantified at the individual level ([5], [46]). Potential modulation of the climatic response is usually assessed by comparing climatic signals from mean chronologies of sub-populations stratified by age, size or competition. However, arbitrary classification of trees would artificially generate contrasting signals in mean sub-population chronologies, simply due to different sample replication ([16]). In addition, the traditional population-based approach magnifies the common signal in a population, and reduces the signal of climatic factors that affect only a fraction of trees ([4], [46]). Such concerns may be avoided by using an individual-based approach, which informs about the relative contribution of factors modulating the climatic response, as this study revealed. Further research is required in order to better understand the prevalence and extent of individual dendroclimatic responses potentially modulated by intrinsic tree traits and extrinsic factors in different tree species.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Enrique Diz, Adrián González, Sonia Lamas, Aurea Pazos and María José Rozados for field and laboratory assistance, José Miguel Olano and three anonymous reviewers for useful suggestions on an earlier draft of this paper, and David Brown for English language assistance. The author benefited from research contracts by INIA-Xunta de Galicia and CSIC, partially funded by the European Social Fund. This study was supported by Consellería de Innovación e Industria, Xunta de Galicia (PGIDIT06PXIB502262PR), and Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agraria y Alimentaria, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (RTA 2006-00117).

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Laboratorio de Dendrocronología, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Austral de Chile, casilla 567, Valdivia (Chile)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Rozas V (2015). Individual-based approach as a useful tool to disentangle the relative importance of tree age, size and inter-tree competition in dendroclimatic studies. iForest 8: 187-194. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1249-007

Academic Editor

Francesco Ripullone

Paper history

Received: Jan 20, 2014

Accepted: May 25, 2014

First online: Aug 21, 2014

Publication Date: Apr 01, 2015

Publication Time: 2.93 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2015

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 57597

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 47065

Abstract Page Views: 4167

PDF Downloads: 4712

Citation/Reference Downloads: 76

XML Downloads: 1577

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 4207

Overall contacts: 57597

Avg. contacts per week: 95.84

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2015): 38

Average cites per year: 3.45

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Species-specific climate response of oaks (Quercus spp.) under identical environmental conditions

vol. 7, pp. 61-69 (online: 18 November 2013)

Research Articles

Species-specific responses of wood growth to flooding and climate in floodplain forests in Central Germany

vol. 12, pp. 226-236 (online: 03 May 2019)

Research Articles

Growth-climate relations and the enhancement of drought signals in pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.) tree-ring chronology in Eastern Hungary

vol. 11, pp. 267-274 (online: 29 March 2018)

Short Communications

Climate effects on growth differ according to height and diameter along the stem in Pinus pinaster Ait.

vol. 11, pp. 237-242 (online: 12 March 2018)

Research Articles

The effect of provenance of historical timber on tree-ring based temperature reconstructions in the Western Central Alps

vol. 13, pp. 351-359 (online: 25 August 2020)

Research Articles

Geographic determinants of spatial patterns of Quercus robur forest stands in Latvia: biophysical conditions and past management

vol. 12, pp. 349-356 (online: 05 July 2019)

Research Articles

Effects of mixture and management on growth dynamics and responses to climate of Quercus robur L. in a restored opencast lignite mine

vol. 15, pp. 391-400 (online: 05 October 2022)

Research Articles

Growth patterns of forest stands - the response towards pollutants and climatic impact

vol. 2, pp. 4-6 (online: 21 January 2009)

Research Articles

Response to climate and influence of ocean-atmosphere phenomena on annual radial increments of Pinus oocarpa Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham in the Lagunas de Montebello National Park, Chiapas, Mexico

vol. 16, pp. 174-181 (online: 30 June 2023)

Research Articles

Influence of tree density on climate-growth relationships in a Pinus pinaster Ait. forest in the northern mountains of Sardinia (Italy)

vol. 8, pp. 456-463 (online: 19 October 2014)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword