Genomics of the Dutch elm disease pathosystem: are we there yet?

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 8, Issue 2, Pages 149-157 (2015)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1211-008

Published: Aug 07, 2014 - Copyright © 2015 SISEF

Review Papers

Collection/Special Issue: 3rd International Elm Conference, Florence (Italy - 2013)

The elms after 100 years of Dutch Elm disease

Guest Editors: A. Santini, L. Ghelardini, E. Collin, A. Solla, J. Brunet, M. Faccoli, A. Scala, S. De Vries, J. Buiteveld

Abstract

During the last decades, the development of ever more powerful genetic, molecular and omic approaches has provided plant pathologists with a wide array of experimental tools for elucidating the intricacies of plant-pathogen interactions and proposing new control strategies. In the case of the Dutch elm disease (DED) pathosystem, these tools have been applied for advancing knowledge of the host (Ulmus spp.) and the causal agents (Ophiostoma ulmi, O. novo-ulmi and O. himal-ulmi). Genetic and molecular analyses have led to the identification, cloning and characterization of a few genes that contribute to parasitic fitness in the pathogens. Quantitative PCR and high-throughput methods, such as expressed sequence tag analysis, have been used for measuring gene expression and identifying subsets of elm genes that are differentially expressed in the presence of O. novo-ulmi. These analyses have also helped identify genes that were differentially expressed in DED fungi grown under defined experimental conditions. Until recently, however, functional analysis of the DED fungi was hampered by the lack of protocols for efficient gene knockout and by the unavailability of a full genome sequence. While the selective inactivation of Ophiostoma genes by insertional mutagenesis remains a challenge, an alternative approach based on RNA interference is now available for down-regulating the expression of targeted genes. In 2013, the genome sequences of O. ulmi and O. novo-ulmi were publicly released. The ongoing annotation of these genomes should spark a new wave of interest in the DED pathosystem, as it should lead to the formal identification of genes modulating parasitic fitness. A better understanding of DED, however, also requires that omic approaches are applied to the study of the other biotic components of this pathosystem.

Keywords

Dutch Elm Disease, Ophiostoma spp., Genetic and Molecular Analyses, Gene Expression, RNA Interference

Introduction

After nearly 100 years of documented Dutch elm disease (DED) presence, it seems only fitting to revisit this pathosystem from a genetic standpoint encompassing both traditional Mendelian genetics and the most recent developments in omic-based approaches. Ideally, this should be done in the context of integrative biology in which all biotic members of the pathosystem, as well as the intricate interactions among them, are considered. This review, however, will emphasize research on the DED pathogens. While this reflects the authors’ expertise on fungi, it was also driven by the consideration that genetic investigations of other components of the pathosystem are lagging, as inferred from a survey of the peer reviewed literature published on DED. There are several reasons for such situation, including the fact that the pathogens are the component of the patho- system that are the most easily analyzed genetically. Since their life cycle is short and can be completed under laboratory conditions, it is possible to cross sexually compatible individuals and obtain F1 progeny within weeks. Highly inbred strains can be produced within one year. Mendelian genetic analysis of the pathogens is therefore easy and the heritability of any scorable phenotypic or genotypic trait can be assessed rapidly. This is clearly not the case for elms which, like other temperate tree species, have a long life cycle and take years before they reach sexual maturity. The small genomes of the DED fungi also facilitate genomic analyses. Molecular and omic approaches, however, represent technological advances that should allow rapid developments in the genetic analysis of elms and bark beetle vectors of the disease. In fact, this has already happened and some examples will be provided in this review.

Many pathosystems involve a single pathogen. In the case of DED, three fungal species are known to induce the disease. Ophiostoma ulmi caused the first DED pandemic, which spread throughout Europe since the early 1900’s to the 1940’s, when it started to decline ([18]). The closely related species O. novo-ulmi is responsible for the second, ongoing pandemic. Two subspecies (novo-ulmi and americana) are recognized within O. novo-ulmi ([20]) which is more virulent (used here as a quantitative trait sensu [66]) and generally fitter than O. ulmi ([18]). Over the years, O. ulmi and O. novo-ulmi were introduced into Europe, North America, central Asia, New Zealand, and Japan ([19], [64]). The third species, O. himal-ulmi, is endemic to the western part of the Himalayas where it is considered an endophyte of native elms ([24]). Controlled inoculations of O. himal-ulmi to U. procera and U. x Commelin, however, have shown that it is pathogenic towards European species and hybrids ([24]). This review will focus on O. novo-ulmi, which is the dominant pathogen in most areas where DED occurs.

Elm genomics

The genus Ulmus comprises over 40 known species that are indigenous to the northern hemisphere ([100]). There is, however, surprisingly little genomic information on elms compared to other broadleaved tree species found in the same parts of the world, such as poplars, beech or oaks ([62], [86]), even though elm breeding programs have been existing for over 80 years ([67]). Molecular and genomic studies of elms were mostly concerned with species identification ([29], [99]), population genetics and structure ([44], [101], [95], [96]), elm conservation ([45]) and introgression between invasive and native elm species ([102], [25]).

Information on the genetic determinants of elm response to biotic stresses such as DED remains fragmentary. Nasmith et al. ([70], [71]) studied in vivo the expression of three genes whose products are associated with plant defense, namely phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), chitinase (CHT) and polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein (PGIP). Based on Northern hybridization results, these authors reported that expression of PGIP and CHT was stronger in DED resistant U. pumila than in DED sensitive U. americana. Furthermore, expression was reported to be tissue-dependent: it was stronger in root tissues than in leaf midrib or inner bark, whereas only PAL expression was detectable in callus cultures ([70]). The latter result corroborated previous observations of PAL activity in cell suspensions of U. pumila and U. campestris exposed to DED fungi ([30]). Aoun et al. ([1]) confirmed that PAL transcripts accumulated in U. americana hard calli inoculated with O. novo-ulmi and that this was correlated with the accumulation of suberin, phenols and lignin.

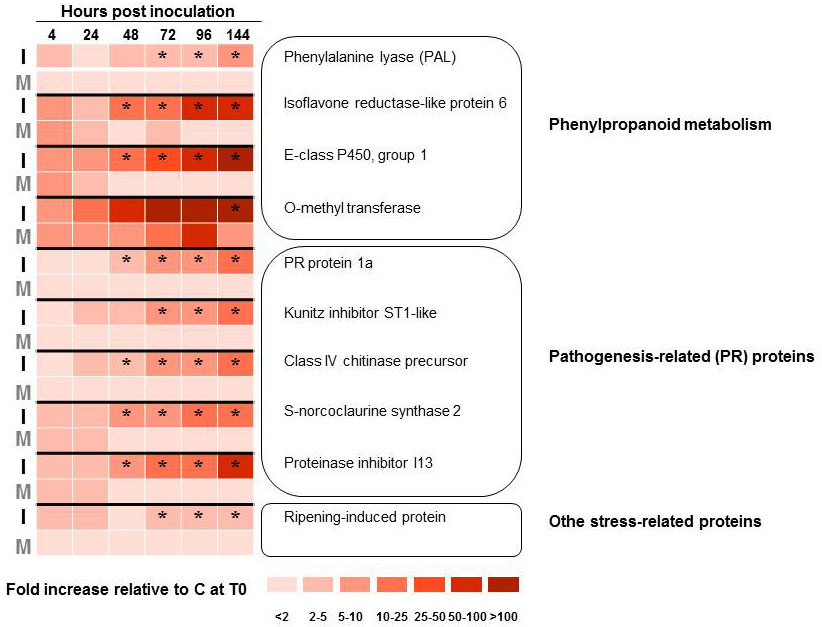

Rather than targeting specific genes, Aoun et al. ([2]) used a large-scale cDNA sequencing approach to study the compatible interaction between O. novo-ulmi and U. americana hard calli. Following bioinformatics analyses of a host-pathogen interaction cDNA library enriched in up-regulated genes by suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH), 296 elm unique sequences were identified from 535 expressed sequence tags (ESTs). A time course analysis of gene expression was carried out on a subset of 18 elm transcripts by quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). Results from transcript profiling confirmed that several genes encoding pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins and enzymes belonging to the phenylpropanoid pathway were up-regulated (Fig. 1). None of the genes studied, however, showed a significant increase in transcription prior to 48 hours after inoculation, which prompted the authors to suggest that the susceptibility of U. americana to DED might result partly from a delay in its response to infection ([2]). More recently, Büchel et al. ([26]) reported on the production and analysis of a much larger elm EST resource. These authors identified 361 196 Ulmus minor ESTs which clustered into 52 823 unique transcripts. While the study focused on the response of U. minor to egg laying by the elm leaf beetle (Xanthogaleruca luteola), the authors showed that up-regulated transcripts included several pathogen-related genes and genes involved in phytohormone (jasmonic acid) signaling.

Fig. 1 - Transcript profiling of 10 Ulmus americana genes that are up-regulated upon infection of hard calli with Ophiostoma novo-ulmi subsp. novo-ulmi. Gene transcription profiles were monitored by quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, with 3 biological replicate and 2 technical replicates. Elm tissues were either mock-inoculated with sterile water (M) or inoculated with yeast-like cells of O. novo-ulmi H327 (I). Results are shown as fold increase in transcription level compared to healthy elm calli (C) harvested at the start of the experiment (T0). Data were analyzed by ANOVA and Tukey’s test. (*): significant difference (P <0.05) between I and M treatments. Data from Aoun et al. ([1], [2]).

Elm bark beetle genomics

Elm bark beetles known to vector DED fungi include species from the genera Scolytus (S. kirchi, S. laevis, S. multistriatus, S. pygmaeus, S. schevyrewi, S. scolytus) and Hylurgopinus (H. rufipes). Unlike several other species of bark beetles which carry fungal associates in special organs called mycangia, elm bark beetles carry DED fungal spores on the surface of their body surface and in their gut ([97], [98], [69]). They also carry phoretic mites which may contribute to increase the O. ulmi / O. novo-ulmi spore load of individual elm bark beetles ([69]). To our knowledge, very limited genomic information on any of the aforementioned species has been published in peer reviewed journals. The National Center for Biological Information (NCBI) database contains only five gene sequences from S. scolytus, which were analyzed within the context of a phylogenetic study of wood boring weevils ([57]). The mitochondrial genome of S. laevis was also sequenced and annotated, again in the context of weevil phylogenetics ([46]). A growing body of information from genome-wide studies, however, is available for species of bark beetles associated with conifers. Thus, population genomics of the mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) have been described in recent years ([68], [43]), whereas Blomquist et al. ([9]) reviewed the functional genomics of pheromone production in Ips pini. The transcriptome of D. ponderosae was recently analyzed by a combination of Sanger sequencing and Roche 454 pyrosequencing of 14 full-length enriched cDNA libraries ([58]). Similar omic studies of elm bark beetles and their interactions with other components of the DED pathosystem are needed, especially in the light of the hypothesis that O. novo-ulmi, by up-regulating the production of semiochemicals in elms, manipulates host trees in order to enhance their apparency to foraging beetles ([65]).

Genomics of Dutch elm disease fungi

The development of PCR-based approaches in the late 1980’s stimulated the analysis of population structure in the DED fungi. Hoegger and co-workers used Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers to show that O. ulmi and the two subspecies of O. novo-ulmi were present in Switzerland ([52]). They further indicated that RAPDs were superior to restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs), used previously ([49], [56], [4]) for distinguishing between subspecies americana and novo-ulmi within O. novo-ulmi. Over the following years, additional population structure studies using PCR-derived markers were conducted in Italy ([83]), Spain ([85]), the Netherlands ([21]) and Canada ([92]). From these and other studies, it is clear that European populations of DED fungi are more diverse than North American ones. Ophiostoma ulmi was still found in parts of Europe in the early 21st century ([85]), whereas this species has not been reported in North America since 1991 ([53]). Moreover, hybrid isolates (between O. ulmi and O. novo-ulmi, between the two subspecies within O. novo-ulmi) are commonly reported in Europe ([52], [22], [19], [61], [83], [21]), but not in North America, where O. novo-ulmi subsp. americana seems to be the sole DED taxon and is characterized by large clonal populations ([92]). The population structure of the North American population of O. novo-ulmi is typical of that of recently-introduced pathogens experiencing a genetic bottleneck, and differs markedly from what has been reported in the closely-related species O. piceae ([41]), as well as in the more distant Ophiostomatoid species Grosmannia clavigera ([94]) which are genetically more diverse and appear to be indigenous to North America.

Molecular identification of genes controlling pathogenicity, virulence and other components of parasitic fitness in the DED fungi has proceeded slowly. So far, only three genes have been subjected to functional analyses. The first one, Cu, encodes the hydrophobin cerato-ulmin (CU) which was proposed to be a wilt toxin and thus a pathogenicity factor ([90]). This hypothesis was weakened following the identification of naturally occurring non-CU producing mutants which were nevertheless pathogenic and virulent ([23]). Furthermore, the Cu gene was cloned by Bowden et al. ([12]) who subsequently produced knockout cu- mutants that remained virulent ([13]). Temple et al. ([91]), based on the analysis of an O. ulmi strain over-expressing CU and an O. novo-ulmi cu- knockout mutant, proposed that CU contributed to parasitic fitness by improving yeast-like spore resistance to desiccation and attachment to the exoskeleton of elm bark beetles. Transcription of the Cu gene was reported to be 20-60% higher in mycelium than in yeast-like cells grown in vitro ([89]). The second gene, Epg1, encodes the lytic enzyme endopolygalacturonase, thought to be important for xylem colonization by DED fungi ([88]). Temple et al. ([93]) obtained epg1- knockout mutants and reported these were not significantly less virulent than the wild-type strain. A third gene, Col1, was identified by Pereira et al. ([77]) following random insertional mutagenesis of O. novo-ulmi with plasmid DNA ([82]). The authors noticed the occurrence of one hygromycin-resistant transformant with an unusually slow colony growth on nutrient agar. The Col1 gene is orthologous to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene coding for U4/U6 splicing factor PRP24. Other genetic loci have been identified in O. novo-ulmi, including the Pat1 locus thought to encode a pathogenicity factor ([37], [38]) and a locus associated with yeast/mycelial growth ([81]), but have not been cloned. Sequences encoding adenylate cyclase ([8]) and chitin synthase ([48]), cloned from O. novo-ulmi, were not studied further.

The DED fungi are heterothallic species in which mating occurs between sexually-compatible individuals carrying different alleles (or idiomorphs) at the mating-type locus, designated MAT1 according to standard genetic nomenclature ([32]). The MAT1-2 idiomorph was cloned by gene-walking ([75]), whereas a portion (MAT1-1-3 gene) of the MAT1-1 idiomorph was retrieved from an EST library derived from O. novo-ulmi subsp. novo-ulmi strain H327 ([54]). The complete sequence of MAT1-1 has since been obtained by gene-walking (Jacobi et al. unpublished) and confirmed by full genome sequencing of strain H327 ([39]). The structure of the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs of DED fungi is similar to structures described in other heterothallic Sordariomycetes. The MAT1-1 idiomorph contains three genes, namely MAT1-1-1, MAT1-1-2 and MAT1-1-3 encoding a α domain, a DNA-binding acidic amphipathic α-helix (HPG) domain, and a DNA-binding domain of the high mobility group (HMG), respectively. The MAT1-2 idiomorph encodes a single protein, a HMG domain. Based on phenotypic characterization of DED fungi, Brasier originally suggested that early populations of O. novo-ulmi consisted uniquely of MAT1-2 individuals and that this species eventually acquired the MAT1-1 idiomorph through interspecific hybridization with O. ulmi ([16]). This hypothesis was later confirmed by genetic mapping of vegetative incompatibility (Vic) and MAT1 loci in a large collection of DED fungi ([76]). Brasier also hypothesized that the MAT1 locus acted as a key regulator of metabolism in the DED fungi ([17]). While the validation of this hypothesis awaits the development of efficient techniques for targeted gene/allele replacement, the acquisition of the MAT1-1 idiomorph by O. novo-ulmi nevertheless illustrates the potential for rapid species evolution through interspecific hybridization. Another example of allele transfer was provided by the genetic and molecular analysis of a strain of O. novo-ulmi (AST27) with unusually low virulence ([37]). Strain AST27 was shown to be an introgressant whose genome was enriched for O. ulmi-type RAPD sequences around the Pat1 locus, suggesting that the latter originated from O. ulmi. The survival of such low-virulent introgressants in nature, however, appears unlikely unless they possess other attributes that may contribute positively to fitness.

Among eukaryotes, fungi are the organisms that are the most amenable to omic approaches because of their small genomes. Filamentous ascomycetes have genomes ranging from 25 to 160 Megabases (Mb) in size, with approximately 8000 to 18000 genes ([59]). In the case of the DED pathogens, original estimates of genome size varied from 30 to 40 Mb based on pulsed field gel electrophoresis data ([33], [34]). In 2013, the genomic sequences of O. novo-ulmi subsp. novo-ulmi ([39]) and O. ulmi ([60]) were released within weeks of each other. The two genomes are very similar in size and gene number, with 31.8 Mb and 8640 nuclear genes predicted in O. novo-ulmi H327, compared to 31.5 Mb and 8639 predicted genes in O. ulmi W9 (Tab. 1). These statistics resemble those of ophiostomatoid associates of conifer bark beetles, such as O. piceae ([47]) and G. clavigera ([35]). When the genomes of these four ophiostomatoid fungi are compared to those of other plant pathogenic ascomycetes, however, one can see that the former are smaller and harbor fewer genes than most of the latter.

Tab. 1 - General features of the genomes of Ophiostoma ulmi, O. novo-ulmi and selected filamentous ascomycetes. (n/a): not applicable.

| Species | Size (Mb) | Nb. Chromosomes | %GC | Nb. Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fusarium oxysporum (Sordariomycetes) | 61.5 | 15 | 48.5 | 17 735 |

| Botrytis cinerea (Leotiomycetes) | 39.5 | n/a | 43.5 | 16 448 |

| Fusarium verticillioides (Sordariomycetes) | 41.9 | 11 | 48.7 | 14 179 |

| Magnaporthe grisea/M. oryzae (Sordariomycetes) | 41 | 7 | 51.6 | 11 074 |

| Neurospora crassa (Sordariomycetes) | 41 | 7 | 48.2 | 9 734 |

| Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Leotiomycetes) | 38.3 | 16 | 41.8 | 14 522 |

| Aspergillus oryzae (Eurotiomycetes) | 37.1 | 8 | 48.2 | 12 063 |

| Fusarium graminearum (Sordariomycetes) | 36.6 | 4 | 48.3 | 13 332 |

| Chaetomium globosum (Sordariomycetes) | 34.9 | n/a | 55.6 | 11 124 |

| O. piceae (Sordariomycetes) | 32.8 | n/a | 52.8 | 8 884 |

| Neosartorya fischeri (Eurotiomycetes) | 32.5 | 8 | 49.4 | 10 406 |

| O. novo-ulmi (Sordariomycetes) | 31.8 | 8 | 49.8 | 8 613 |

| O. ulmi (Sordariomycetes) | 31.5 | n/a | 50 | 8 639 |

| Aspergillus nidulans/E. nidulans (Eurotiomycetes) | 30.1 | 8 | 50.3 | 10 560 |

| Grosmannia clavigera (Sordariomycetes) | 29.8 | 7 | 53.4 | 8 301 |

The sequencing of the genomes of O. novo-ulmi H327 and O. ulmi W9 represents a long-awaited accomplishment, but is only the beginning of a new phase of research on the DED fungi. The O. novo-ulmi H327 sequencing project ([39]) focused on reproducibility and quality control of the Roche 454 Titanium pyrosequencing technology, which resulted in obtaining a genome with high coverage (over 60X). This, plus the inclusion of additional paired-end sequencing, permitted the assembly of the nuclear genome into 8 scaffolds corresponding to chromosomes, and the full sequencing of the mitochondrial genome (66.4 Kb, 15 predicted genes). On the other hand, none of the 8640 nuclear genes predicted by automated gene-calling algorithms was annotated. Conversely, the genome of O. ulmi W9 ([60]) was not sequenced with the same depth and, as a consequence, could only be scaffolded and not completely assembled. The authors of this work, however, were able to provide an initial annotation of the O. ulmi W9 genome based on transcriptional data obtained by large-scale RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq).

The important work of O. novo-ulmi H327 annotation and comparison to other Sordariomycetes is currently underway in our group (Comeau et al. unpublished). Preliminary results show that approximately 76% of the proteins could be assigned functions using Gene Ontology analysis (Blast2GO). Additionally, 276 carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), 48 cytochrome P450s, and 763 proteins potentially involved in pathogen-host interaction, along with 8 clusters of fungal secondary metabolites, have been identified through searches in public databases. A relatively small portion of the genome is occupied by repeat sequences, however the mechanism of repeat-induced point mutation (RIP; see below) appears active in this genome.

A genome-to-genome alignment between O. novo-ulmi H327 against the appropriate scaffold from O. ulmi W9 showed a large region around the previously mentioned MAT1 locus has very high identity between the two, consistent with the hypothesis of Paoletti et al. ([76]) that the MAT1-1 idiomorph was recently acquired by O. novo-ulmi from O. ulmi. Finally, on-going analyses of H327 peptidases, CAZymes and cytochrome P450s are showing various mechanisms and pathways whereby the fungus is able to detoxify and/or transform elm defenses (such as glycoproteins, phytoalexins and terpenes) in order to thrive in its interaction with its plant host and insect vector.

The genomes of Ophiostoma spp., like all eukaryotes, contain transposable elements (TEs) which can be divided into two main groups: Type I TEs include retrotransposons, whereas the Type II group is constituted by DNA transposons. Transposable elements can potentially generate novel phenotypes in their hosts. Three Type II TEs (OPHIO1, OPHIO2 and OPHIO3) were originally described and characterized in O. ulmi and O. novo-ulmi ([10], [11]). OPHIO transposons occur in low copy number (less than 10 copies) per genome, suggesting that they appeared recently in ophiostomatoid genomes. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that OPHIO1 and OPHIO2 are restricted to O. ulmi and O. novo-ulmi subsp. novo-ulmi ([10]) and can be induced to move from their genomic location by various biotic and abiotic stresses ([11]), which are two characteristics of a recent invasion. Based on the high variability of its Southern hybridization profiles, OPHIO2 seems to have the highest level of mobility among OPHIO TEs. On the other hand, transposon OPHIO3 displays less variation in its Southern hybridization profiles and was found to be heavily modified by RIP. The latter is a mechanism found in many fungi which allows them to inactivate repeated sequences prior to or during sexual recombination. RIP is a homology- dependent genome defense that introduces cytosine-to-thymine transition mutations in duplicated DNA sequences and is thought to control the proliferation of selfish repetitive DNA. Why only OPHIO3, and not OPHIO1 and OPHIO2, was found to be RIPed in the DED fungal strains examined so far remains an open question. In addition, the extent to which TEs contribute to genomic and phenotypic plasticity of DED fungi remains unknown.

Surveys of natural populations of DED fungi have led to the identification of diseased individuals that display reduced growth rates, unstable “amoeboid” colony morphologies, low spore viability, decreased reproductive ability, and reduced virulence ([15], [87], [51]). The lower fitness of such individuals is not the result of nuclear mutations. Rather, this particular phenotype has been associated with the presence of cytoplasmic elements originally known as d-factors ([15]) which have since been found to be double-stranded RNA viruses located in the mitochondria (mitoviruses). At least 15 different mitoviruses have been described in the DED fungi ([51]), and genome sequences for nine of these are available in the NCBI database. How the mitoviruses found in O. ulmi and O. novo-ulmi act on their fungal host is unknown, but their dramatic effect on fungal physiology has prompted researchers to speculate on their use for biological control of DED ([51]). One additional feature of the mitochondrial genome of DED fungi is the occurrence of LAGLIDADG homing endonuclease (Heg) genes within the Rps3 gene encoding ribosomal protein S3 ([84]). The biological significance of the presence of Heg genes in the mitochondrial genome of DED fungi, however, is not known.

Development of tools for genomic studies of the DED pathosystem

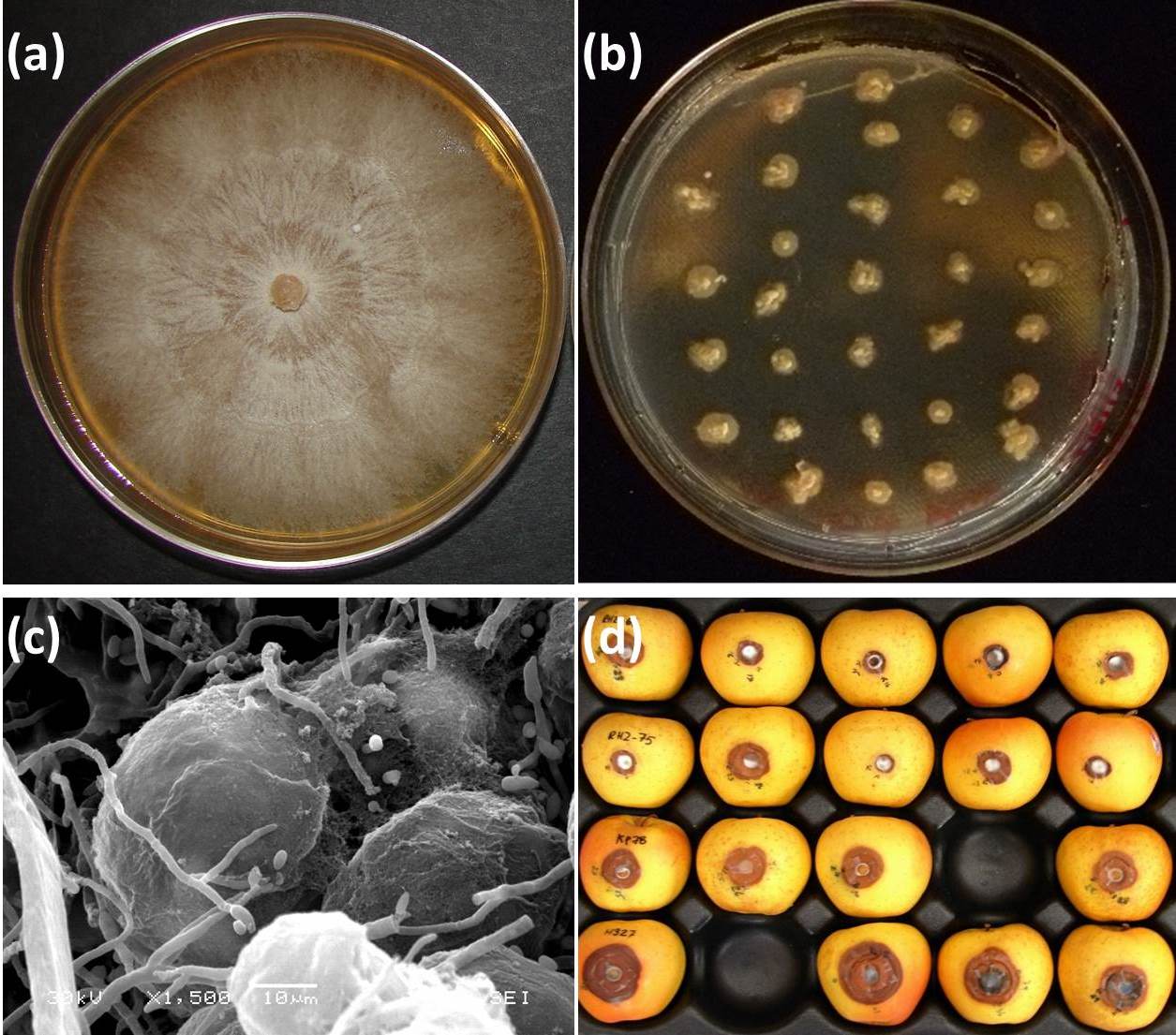

In order for the DED pathosystem to fully enter the omic era, tools and resources are required. Some of these tools are already available, whereas others need to be developed. In the case of the pathogens, omics are facilitated by the availability of simple procedures (Fig. 2) established decades ago for growing large numbers of colonies on solid media amended with deoxycholic acid ([5], [6]), manipulating environmental parameters for obtaining either yeast or mycelial growth phases ([63]), and obtaining both asexual and sexual fruiting structures in vitro ([14], [6]). This has facilitated the construction of an EST expression library for the yeast growth phase of O. novo-ulmi ([50]), as well as smaller EST datasets associated with the production of synnemata and perithecia ([54]). These are valuable resources for elucidating the molecular bases of biological functions in the DED fungi.

Fig. 2 - Approaches for screening high numbers of DED fungal strains in vitro. Extensive mycelial growth on standard solid media (a) precludes testing of several individuals on a single culture dish. Addition of deoxycholic acid (0.01%, v/v) induces a colonial growth pattern (b), without affecting cell germination, thus facilitating screening either directly or by replica plating. Callus tissues grown on solid media are suitable material for analyzing host-pathogen interactions (c). “Golden Delicious” apples (d) provide a rapid and efficient bioassay for around-the-year screening of mutant DED fungal strains derived from wild-type strain (arrow). Figure prepared from original data from Bernier & Hubbes ([5]), Aoun et al. ([2]), and Plourde & Bernier ([79]).

The mere association of ESTs with a given function, however, is not sufficient. Eventually, mutants are required for establishing the role of specific genes in these functions. As mentioned earlier in this review, genetic transformation of O. novo-ulmi was achieved in the early 1990s ([82]) and has been used both for random insertional mutagenesis ([77], [80]) and inactivation of selected genes ([13], [93]). Problems, however, must be overcome before insertional mutants with the desired phenotype are recovered efficiently in the DED fungi. In the case of random insertional mutagenesis, it has proven difficult to clone mutated loci by recovering Ophiostoma DNA sequences flanking the plasmid insertion site due to large rearrangements ([80]). On the other hand, targeted inactivation of specific genes may require a large screening effort: Temple et al. ([93]) reported recovering one true Δepg1 knockout mutants out of 50 transformants, whereas Bowden et al. ([13]) had to screen 2500 transformants in order to recover one Δcu mutant. We recently recovered a mutant of O. novo-ulmi in which the gene Mus52, involved in non-homologous DNA repair ([73]), has been inactivated (Naruzawa et al., unpublished). We are now using this Δmus52 strain in further gene replacement experiments and assessing whether this improves the frequency at which knockout mutants are recovered. Meanwhile, protocols have been developed for gene knockdown in O. novo-ulmi by RNA interference (RNAi) technology ([27]). Furthermore, RNAi constructions including an endogenous promoter are now available for controlling the expression of the targeted gene by changing the source of carbon in the growth medium ([28]).

The EST expression libraries produced so far for the DED fungi are limited in scope. They are relatively small and only represent three physiological stages: the largest library, from yeast cells, contains 4386 sequences representing 2093 genes ([50]), whereas the SSH-enriched libraries described by Jacobi et al. ([54]) for synnemata and perithecia are even smaller, with tags for 181 and 128 genes, respectively. These libraries were constructed and analyzed at a time when ESTs were considered the most economical way to investigate the fungal transcriptome. This is no longer the case since newer technologies such as genome-wide RNA sequencing offer a much deeper coverage of the transcriptome for a fraction of the cost of standard EST analysis. This approach was used by Khoshraftar and colleagues to get a first glimpse of the transcriptome of O. ulmi W9 yeast cultures. Approximately 80% of the gene models identified ab initio were represented by at least one transcript in the O. ulmi W9 RNA-Seq dataset ([60]), which represents a ca 3.5-fold improvement over previous EST data for O. novo-ulmi H327 ([50]). The above-mentioned studies, however, were exploratory and did not include biological replicates. We are currently carrying out replicated RNA-Seq comparative analyses of the transcriptomes of yeast and mycelial cultures of O. novo-ulmi H327 in order to identify subsets of genes whose expression differs significantly between the two growth forms (Nigg et al. unpublished).

While no draft genome is available for any species within the genus Ulmus, resources are nevertheless available for elm omics and could help in the study of host-pathogen (or host-vector) interactions. The large EST dataset for the interaction between U. minor and the elm leaf beetle X. luteola ([26]) is by far the most complete investigation into the elm transcriptome and likely contains information that can be used in the study of DED. The latter can be further facilitated by using elm cell cultures (Fig. 2), either in liquid medium ([30]) or on solid substrate ([78]). While it may be argued that elm calli do not possess the characteristic arrangement of differentiated xylem in saplings and trees, they nevertheless express defense responses (such as accumulation of phenolics and production of suberin layers) typically encountered in trees ([1]). Furthermore, they are more amenable than xylem tissue from twigs, branches or stem for transcriptomic analyses ([2]). Putative defense-related genes identified in elm calli inoculated with the DED pathogens could be further characterized in saplings, through genetic transformation ([42], [72]). Although gene knockout experiments resulting in loss of function cannot be currently envisioned, gain of function through overexpression of selected genes following ectopic transformation is theoretically feasible.

Functional genomics of any pathosystem also requires that large-scale assays of mutant fungal strains or plant lines are carried out efficiently and in a cost-effective manner. In the case of DED, this rules out the inoculation of large sets of mutant Ophiostoma strains to elm saplings, because such inoculations are time- and material-consuming, must be conducted under confinement (especially when transformants of Ophiostoma and/or Ulmus are used), and require that inoculated elms be “receptive”, i.e., that they are inoculated when they are producing early wood. The use of elm tissue cultures alleviates some of these problems but remains technologically demanding. We recently adapted an apple based-assay (Fig. 2), designed originally for testing the virulence of the chestnut blight pathogen Cryphonectria parasitica ([40]), for screening a library of insertional mutants of O. novo-ulmi H327 ([79]). Parallel experiments in which mutants were inoculated to “Golden Delicious” apples and Ulmus parvifolia x U. americana hybrid saplings confirmed that the apple assay could be used to identify rapidly mutants with altered levels of virulence. This assay thus represents a useful tool for year-round screening of large numbers of O. novo-ulmi transformants. It could also likely be used for studying virulence in O. himal-ulmi (Bernier et al. unpublished).

Some aspects of DED worth visiting or revisiting

The interaction between Ulmus and pathogenic Ophiostomas has often been considered in a very reductionist way. For example, individual molecules such as cerato-ulmin ([90]) and peptidorhamnomannans ([74]) were proposed as pathogenicity factors in O. novo-ulmi, whereas resistance was associated with the production of mansonone phytoalexins ([55]). This oversimplified view of DED was in good part rooted in the type of experimental approaches that were available at the time. The omic revolution is rapidly changing the way we can address biological questions such as DED. The first analyses of the elm transcriptome have indeed shown that exposure to the pathogen ([2]) or to eggs from leaf defoliators ([26]) triggers a large array of genes coding for proteins involved in several different pathways. This is all the more obvious in the analysis carried out by Büchel et al. ([26]) which showed that insects triggered responses that were also associated with pathogens. One can expect similar observations for the pathogen once Ophiostoma transcriptomes are systematically assessed from cultures harvested at different physiological states or exposed to various environmental conditions. For example, recent work on thermally controlled yeast-mycelium dimorphism in Histoplasma capsulatum, a soil-inhabiting pathogen of mammals, provides a genome-wide view of the complex transcriptional network linking pathogenicity and morphology in this species ([7]). Likewise, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that ongoing transcriptomic analyses of yeast-mycelium dimorphism in O. novo-ulmi will reveal significant shifts in the transcription of large subsets of genes. In the near future, comparative genomic studies of elms with other tree species, and of the DED fungi with pathogenic species and with saprobes will likely help identify sets of genes that are common to most (if not all) plant-pathogen interactions, genes that may be specific to vascular wilts, and genes that are unique to the DED pathosystem. A partial list of features of the DED pathosystem that might be unravelled in future genomic investigations is presented in Tab. 2.

Tab. 2 - Some features of the Dutch elm disease pathosystem amenable to omic investigations.

| Host | - Production of a draft genome for an Ulmus species |

| - In silico identification of putative resistance genes by comparative genomics | |

| - Marker-assisted breeding of elms combining higher DED resistance and other desired traits | |

| - Production of DED resistant elms by targeted mutagenesis | |

| Pathogen | - Production of a draft genome for O. novo-ulmi subsp. americana and O. himal-ulmi |

| - In silico identification of putative pathogenicity and virulence genes by comparative genomics | |

| - Development of efficient procedures for producing knockout mutants | |

| - Functional analyses of other fitness traits, such as yeast-mycelium dimorphism, mating-type switching, and resistance to biotic/abiotic stresses | |

| - Determination of the fate and function of transposons and mycoviruses | |

| Vector | - Production of a draft genome for Hylurgopinus rufipes and/or a Scolytus species |

| - In silico identification of putative genes encoding elm and bark beetle pheromone receptors | |

| - Analysis of intraspecific and interspecific variation for targeted genes | |

| Dutch elm disease interactome |

- Transcriptomic analysis of elm bark beetle pheromone response genes in the presence of elm volatiles associated with healthy (feeding) and moribund (egg laying) elms |

| -Transcriptomic analysis of elm response to young elm bark beetle adults feeding on phloem | |

| - Large-scale transcriptomic analysis of elm response to DED fungi | |

| - Gain/loss-of-function studies of targeted genes in host, pathogen and vector | |

| - Analysis of microbial diversity in elm bark beetle breeding galleries |

Concluding Remarks

Dutch elm disease is one of the most studied and documented fungal diseases of trees and has long been considered a textbook example of the devastating impact of exotic pathogens on plant populations. The last decades, however, have coincided with a dramatic decline in DED research, as only a few research groups are still actively studying this pathosystem. Ironically, this is happening at a time when powerful new analytical methods are available for gaining new insight into the biology of the protagonists. Meanwhile, omic approaches are being used for investigating other tree-pathogen interactions, such as chestnut blight ([3]), Melampsora poplar leaf rust ([36]) or sudden oak death ([31]). Pathogenomics of DED is clearly lagging behind the above systems, for reasons which are not biological in nature, as should be clear from the examples provided throughout this review. Rather, DED falls somewhere in the grey zone between the Melampsora poplar leaf rust “model pathosystem” and emerging diseases (such as ash dieback) which are now monopolizing attention and financial resources. Researchers interested in elms and their interactions with the environment should look at initiatives such as the Fagaceae Genomics Web (⇒ http://www. fagaceae.org) which has helped the chestnut blight research community secure funding for omic research, and has resulted in the creation of a large, public database for several tree species within the Fagaceae. Isn’t it time for a cooperative, large-scale international research effort on DED, a disease with such historical and global impact?

Acknowledgements

The authors’ work on Dutch elm disease was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada and Fonds de recherche du Québec-Nature et technologies (FRQNT). Sequencing and assembly of the O. novo-ulmi subsp. novo-ulmi H327 genome was led by K. Dewar (McGill University, Montreal, Canada) and part of the ABRF/ DSRG 2010 study, supported by the Association of Biomolecular Resource Facilities and by Roche/454.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Mirella Aoun

Guillaume F Bouvet

André Comeau

Josée Dufour

Erika S Naruzawa

Martha Nigg

Karine V Plourde

Centre d’étude de la Forêt, Pavillon C-E-Marchand, 1030 avenue de la Médecine, Université Laval, G1V 0A6 Québec, QC (Canada)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Bernier L, Aoun M, Bouvet GF, Comeau A, Dufour J, Naruzawa ES, Nigg M, Plourde KV (2015). Genomics of the Dutch elm disease pathosystem: are we there yet?. iForest 8: 149-157. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1211-008

Academic Editor

Alberto Santini

Paper history

Received: Dec 23, 2013

Accepted: May 03, 2014

First online: Aug 07, 2014

Publication Date: Apr 01, 2015

Publication Time: 3.20 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2015

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 58658

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 48327

Abstract Page Views: 4245

PDF Downloads: 4459

Citation/Reference Downloads: 41

XML Downloads: 1586

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 4211

Overall contacts: 58658

Avg. contacts per week: 97.51

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2015): 13

Average cites per year: 1.18

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Review Papers

Dutch elm disease and elm bark beetles: a century of association

vol. 8, pp. 126-134 (online: 07 August 2014)

Research Articles

Monitoring of the incidence of Dutch Elm Disease and mortality in experimental plantations of French Ulmus minor clones

vol. 15, pp. 289-298 (online: 29 July 2022)

Research Articles

Comparison of commercial elm cultivars and promising unreleased Dutch clones for resistance to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi

vol. 8, pp. 158-164 (online: 07 August 2014)

Research Articles

Seven Ulmus minor clones tolerant to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi registered as forest reproductive material in Spain

vol. 8, pp. 172-180 (online: 13 August 2014)

Review Papers

Avoidance by early flushing: a new perspective on Dutch elm disease research

vol. 2, pp. 143-153 (online: 30 July 2009)

Research Articles

Genetic variation and heritability estimates of Ulmus minor and Ulmus pumila hybrids for budburst, growth and tolerance to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi

vol. 8, pp. 422-430 (online: 15 December 2014)

Research Articles

Genetic variation of Fraxinus excelsior half-sib families in response to ash dieback disease following simulated spring frost and summer drought treatments

vol. 9, pp. 12-22 (online: 08 September 2015)

Research Articles

Arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization in black poplar roots after defoliation by a non-native and a native insect

vol. 9, pp. 868-874 (online: 29 August 2016)

Research Articles

Adaptive response of Pinus monticola driven by positive selection upon resistance gene analogs (RGAs) of the TIR-NBS-LRR subfamily

vol. 10, pp. 237-241 (online: 02 February 2017)

Commentaries & Perspectives

The genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation: the case of forests

vol. 2, pp. 75-76 (online: 10 June 2009)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword