Improved estimates of per-plot basal area from angle count inventories

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 7, Issue 3, Pages 178-185 (2014)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1158-007

Published: Feb 17, 2014 - Copyright © 2014 SISEF

Technical Advances

Abstract

Forest inventories were originally designed for the assessment of timber stocks over large areas. The large datasets gathered by these programs are becoming of increasing interest in other applications, particularly in ecosystem modeling. With inventory designs based on sampling proportional to size (angle-count plots) users should be cautious of using data pertaining to individual plots, as the plot-wise data is a statistical estimate rather than a true measurement. Estimates of per-plot basal area are mathematically unbiased, but the individual precision is extremely poor. Resampling of inventory datasets using multiple basal area factors can improve the precision of the estimates on single plots, thus providing better data for potential end users. Following two simulation studies to demonstrate our method we apply it to the sampling points of the Austrian National Forest Inventory, and show how the improved estimates of basal area give rise to more realistic estimates of basal area increment on individual points, reducing variance through the smoothing of extreme estimates. Our method will be useful in studies where angle count inventory data pertaining to individual plots is used to assess the precision of models or remote sensing methods.

Keywords

Inventory, Basal Area, Sampling Proportional to Size, Resampling, Bitterlich

Introduction

Basal area is a key descriptor of a forest stand, and is often used to estimate other forest attributes such as biodiversity indices ([20]), as a key parameter of ecological habitat models ([30], [9]) or as validation data for large scale ecosystem models ([3]). National Forest Inventories comprise large bodies of individual tree measurements, usually derived from intensive field sampling. Such inventories were traditionally designed to efficiently estimate the standing stock of timber available in large spatial areas, but this data is increasingly being used in other, more ecologically based applications. However, for inventories that use the common “sampling proportional to size” design (angle-count plots - [2]) the data available for individual plots is a point estimate (not a spatially explicit measurement as available from fixed-area plots). Large numbers of angle-count plots must thus be aggregated to attain an adequate estimate of mean basal area. This is problematic in applications where the data from each single plot is assumed to be a reasonably accurate representation of conditions on that plot and regressed against some prediction or dependent variable. This problem is particularly acute when angle-count inventory data is used to evaluate the performance of forest growth models (i.e., [5], [14]); while the full inventory (aggregating all points) may be ideal for assessing model bias, the uncertainty of the individual plot-level data makes evaluation of model precision impossible. We present here a new method of obtaining more useful estimates of basal area on single angle-count plots through the resampling of a National Forest Inventory (NFI) database.

When inventory data is used for its designed purpose (the assessment of mean basal area or volume over large areas) the imprecision of individual plot data is not relevant, as (presumably) the sample design of the inventory uses sufficient plots to reduce standard errors to useful limits. Recently however large-scale inventory data is being used in carbon budget studies (i.e., [1], [19]), to derive estimates of historic forest management practices ([6], [7]), to model forest growth dynamics ([4], [17]), to study forest damage ([16]) and in a host of other applications. Mäkelä et al. ([21]) have pointed out the advantages of using permanent plot NFI records for model development and calibration, highlighting the broad-scale representativeness of the datasets.

Sophisticated forest models usually have intensive data requirements, and NFI data is potentially an extremely valuable resource. Many models can be run in a point-based, scale indeterminate fashion to avoid the assumption that single-point data is fully representative of an area ([27]), but the non-linear nature of many modelled processes means that imprecision in the input data can lead to biased outputs, even though the inputs may be an unbiased representation of the population.

If stand basal area is used as an independent variable in any application, its improved estimation can only lead to better models and clearer understanding of its impact on stand density dependent attributes of forested ecosystems. Although inventory purists may argue that this is a misuse of data collected for a single specific purpose, the scope, comprehensiveness, reliability and high collection cost of NFI datasets demands that efforts should be directed at how to validly use this data in other applications.

A fixed-area inventory plot (“sampling proportional to area”) comprises an exhaustive sample of all trees of above some defined size, in a predefined area. In the context of the broader inventory it is a single sample, and while it should never be considered as being representative of the surrounding region it is nevertheless a complete record of the target population that exists within the plot boundaries. Nested fixed area plots are similar, with the constraint that in the larger plots the target population is restricted to the larger trees. An angle-count plot is different, in that trees are selected as being in or out of the sample based on the relationship between their diameter at breast height (dbh) and their distance from the plot centre (R). Trees whose subtended angle is greater than some predefined figure are counted “in”, thus large trees may be included at greater distances than small trees. Mathematically, if K is the predefined “basal area factor”, then (with dbh in cm and R in m) a tree is included in the sample when dbh2/4R2 > K ([2]).

In metric units, K is normally expressed in m2 ha-1, thus the number of trees counted “in” the sample multiplied by K is the estimated basal area of the stand. The angle-count method has been comprehensively proven to provide unbiased estimates of basal area both in theory ([22]) and in practice (e.g., [29]), assuming the absence of measurement error ([8]). Unlike a fixed-area sample, a single angle-count sample is not exhaustive of all trees and does not relate to a definable area. Also, the basal area estimate must be an integer multiple of K, which (for a single estimate) is unlikely to be a precise reflection of reality. A single fixed-area sample may validly be called a “measurement” of basal area that pertains to a given bounded location, but an angle-count sample cannot. The degree of variation in angle-count estimates is such that a single plot value is of little practical use, and the normal procedure for assessing basal area within particular stands with angle-counts is to make several estimates from different points within a stand and average the results.

National Forest Inventories are commonly designed as systematic and/or cluster sampled grids, and (in central Europe) the points are generally too far apart to be considered as being in the same stand. For their design purpose of estimating national-scale forest attributes this is fine, but for stand-scale basal area assessment the angle-count method (as implemented in NFIs) represents a serious disadvantage. We show in this paper however that it is possible to develop a more useful estimation of basal area on single plots, through resampling the original dataset. While an angle-count based estimate from a single point will not approach the precision of a single fixed-area measurement within the area measured (which is of course the true value inside that area), the improvements gained through the methods presented in this study may improve precision enough that they become more useful in future applications.

Stöhr ([28]) suggested using variable basal area factors for improving the accuracy of the estimated basal area in stands using different angles. Stöhr’s method relied on recording and ranking the subtended angles between the trees and plot centers which effectively results in different or multiple basal area factors. This principle was later pursued by Spurr ([26]). Later, Schieler ([24]) proposed using different angle count factors to test for the problem of overlooked trees within angle count sampling.

The objective of this study is to improve the precision of angle count estimates on individual points through resampling the original database using multiple basal area factors. We first demonstrate the principle through two simulation studies:

- to establish that the new estimates of basal area have an improved root mean square error on plots where true basal area is known, and

- to show how our new estimates of basal area are more useful for model evaluation than the original estimates on plots where the true basal area is not known.

We then apply our method to data of the Austrian National Forest Inventory, showing substantial improvements in estimates at the individual plot level.

Methods

Simulation 1

In this example we simulate four regular stands of trees, on square spacing, with densities of 324, 400, 784 and 1936 stems per hectare (as might be found in a timber plantation). All trees are identical and have a beginning dbh of 11cm. dbh increases by 1 centimeter per year until the simulation ends at dbh = 30cm. Assigning Cartesian coordinate (0, 0) meters to the center of one square of trees, sample points are established at coordinates: (0, 0); (0, 0.5); (0, 1); (0, 1.5); (0, 2); (0.5, 0.5); (1, 1); (1.5, 1.5); and (2, 2) (nine unique sample points). From each point, a series of angle-count estimates of basal area is made using basal area factors (BAFs) of 4.0, 4.1, 4.2 … 8.0 for each year of the simulation. The lists of trees counted “in” the plots with BAFs > 4.0 are clearly subsets of the lists made with BAF = 4.0, so this process equates to resampling a dataset created with BAF = 4.0. The purpose of this exercise is to compare the precision of point estimates made with a BAF of 4.0 against estimates made using the mean of the estimates (from single points) from the multiple BAFs. We do this using the root mean square error (RMSE) of the estimates compared to the basal area implied by the known tree spacing of each stand in each year. The RMSE for each time series of twenty years is calculated for each stand from each sample point and displayed as a boxplot of the nine values for each of the four stands.

Simulation 2

In the second simulation we establish 1000 stands of randomly located trees, of undefined extent. All trees are identical and increase from 11 to 30cm dbh over 20 years, as in the prior example. From a centrally located sample point we make annual estimates of basal area density in each stand (G) using a BAF of 4.0 and the multiple BAF mean, as above.

As the extent of each stand is undefined, the “true’ value of the basal area surrounding each sample point cannot be determined. Assuming that we know however that there is no regeneration or mortality and the rate of dbh growth remain constant, we can fit a simple model to the estimates obtained, and assess the consistency of that model with its own assumptions. As the dbh of the trees is known (and thus the individual tree basal areas), we can use the estimated stand basal area to find the apparent stem density per hectare n (eqn. 1). With the condition that all diameters are equal:

From each 20 year time series we extract 17 groups of four consecutive years. The first two years of each of these are used to estimate n (through fitting a least squares model) with both BAF = 4.0 and the mean of the multiple BAF estimates. Each model is then tested against a similar model fit to the estimations from the third and fourth years, and the results expressed as the root mean square difference between the means of the 17 model pairs. The intention of this simulation is to mimic a common practice in model evaluation; a model is calibrated using data from one time period and its predictions “validated’ against data from a later period. In this case, the “model” is the least squares estimation of n based on the known stem diameters and the estimated stand basal areas.

NFI

The modern “permanent plot” Austrian National Forest Inventory made its first measurements in 1981, following two previous national inventories conducted with a temporary plot design. Inventory measurements covered the periods 1981-1985, 1986-1990, 1992-1996, 2000-2002 and 2007-2009. The inventory is organized into tracts each of 4 points on a 200 m square. 5600 such tracts are arranged in a square grid pattern across the country, including over areas that are not currently forested. Inventory field methods are fully described by Schieler & Hauk ([23]). The inventory uses a basal area factor of 4.0 for all trees of greater than 10.4cm dbh. In this study we use data for the 1915 points on the southeast corner of each tract that contain records for all periods from 3 onwards.

Because the Austrian NFI records tree diameters and locations, we may resample the available dataset to determine which trees would have been counted as “in” if BAFs greater than 4.0 had been used. In this study we apply BAFs from 4.0 to 8.0 in steps of 0.1, and thus obtain 41 different (but in theory, equally unbiased) estimates of basal area surrounding each inventory point in each period.

The precision of the estimates is assessed by examining the variance at each point of the basal area increment between periods. Increment, by definition, is the difference in basal area between two time periods, plus the basal area of any trees removed from the plot. Directly calculating increment in this manner (the “Difference” method) is however extremely imprecise, and as early as the 1950s Grosenbaugh ([10]) developed the “Starting Value” method to reduce the variance in increment estimates. In essence this is an upscaling of the observed increment of individual sampled trees plus the basal area of trees that have grown over the minimum diameter threshold. A disadvantage of this method is that on individual plots the estimated increment is not necessarily equal to the difference in basal area plus removals (non-additive - [18]). For a detailed discussion of these methods and their variance see Hradetzky ([13]). The Starting Value method estimates only increment, it is not applicable to basal area estimation. Over a very large number of plots either method should indicate the same mean increment ([11]), but experience shows that there is extremely poor correlation between estimates for each individual plot. Our purpose here is not to derive better estimates of increment, rather, we use the increment estimates as a means of assessing the precision of the basal area estimates.

In an angle count inventory using a single BAF it is common for the data on a single point to suggest that no increment occurred; i.e., no new tree entered the sample in the subsequent sample due to the spatial arrangement of trees surrounding the point. Conversely, data on many points suggest an unrealistically large increment for the same reason. Although increment is expected to change in time somewhat due to forest age or environmental factors, when using the Difference method the apparent extreme changes in increment on individual plots are more likely to be artefacts of the angle count. The imprecision arises not through any fault in the Difference method itself (which is simply a direct application of the definition of increment), but through the imprecision of the two basal area estimates used in the calculation. It follows then that if increment variance can be reduced, the estimates of basal area used to derive the increment are likely to be more precise.

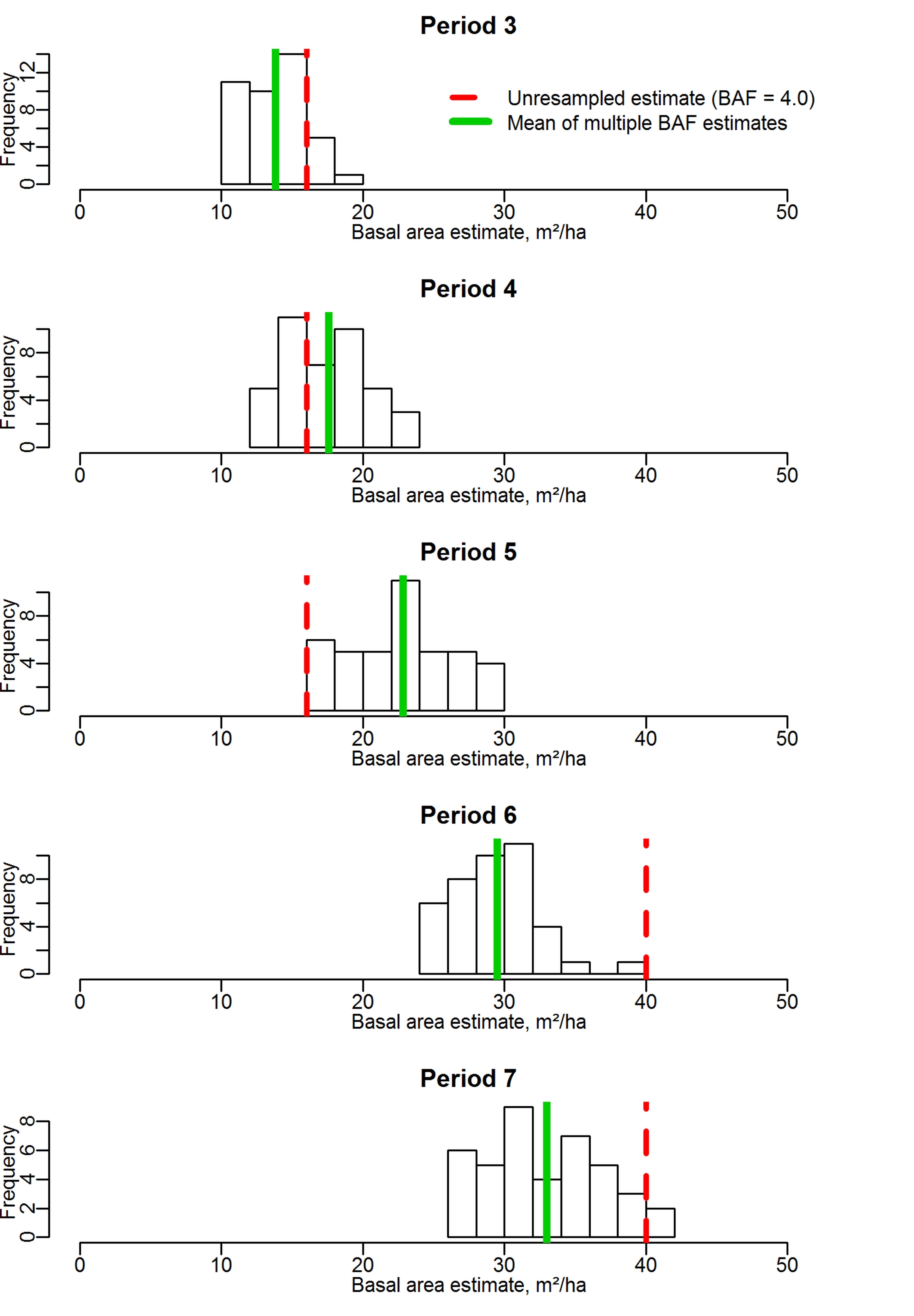

Fig. 1 shows a demonstration of how the method provides improved estimates of basal area on an individual plot, and how this improvement is assessed using increment estimates. The 5 histograms show the frequency of estimated basal area using the 41 different BAFs, in each of the 5 inventory periods. The mean of the estimates is shown as a solid green line, while the estimate from the original, unresampled NFI data with a BAF of 4.0 is shown as a dashed red line.

Fig. 1 - Demonstration of improved basal area estimation using multiple BAFs. Histograms show the distribution of all estimates on a single NFI plot, using BAFs ranging from 4.0 to 8.0.

The original data shows that four trees were in the sample on this plot in periods 3, 4 and 5. In periods 6 and 7, 10 trees were present. The interperiod increments suggested by this are thus 0, 0, 24 and 0 m2 ha-1, which gives a mean of 6.0 m2 ha-1 period-1 and a plotwise variance of increment estimation of 144.0. Increments according to the multiple BAF method are 3.8, 5.3, 6.6 and 3.5 m2 ha-1 period-1, with a mean of 4.8 m2 ha-1 and a plotwise variance of only 2.1. Although this is an extreme example of the possible improvements, it illustrates how we assess that improvement: if the variance in the plotwise increment estimates is reduced, then the basal area estimates are more precise.

Results

Simulation 1

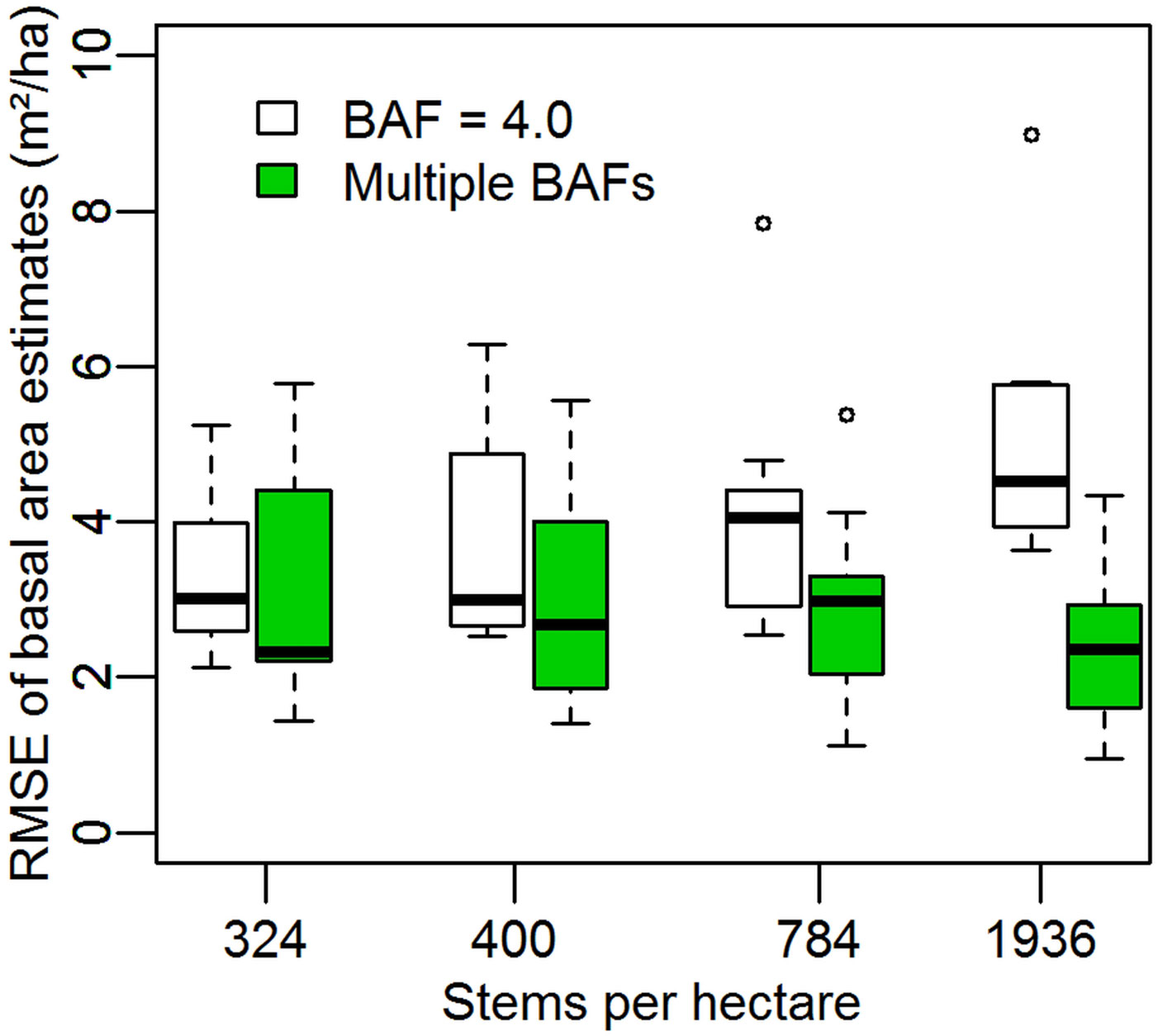

On each of the four simulated regular stands of trees the multiple BAF estimate has a lower RMSE than the estimates using only a BAF of 4.0 (Fig. 2). The improvement is more pronounced at higher stem densities, at 1936 stems per hectare the BAF = 4.0 estimate has a mean RMSE of 5.03 m2 ha-1 (7.30% of the mean basal area of 68.96 m2 ha-1 throughout the simulated period) and the multiple BAF estimate has a mean RMSE of 2.39 m2 ha-1 (3.47%). Wilcoxon signed rank tests suggest all differences are significant at p < 0.004 except for the simulation with 324 stems per hectare, which is not significant (p = 0.570). The outliers and highest whisker extents seen in Fig. 2 are all from the simulation with the point coordinate (0, 0), as in this case multiple sets of four trees are equidistant from the sample point.

Fig. 2 - Root mean square errors of stand basal area estimation in regular stands. Boxes show the median and distribution of RMSEs using nine different sample points in forests of four different stem densities arranged in regular square grids. Open boxes are for estimates made with a basal area factor of 4.0, while solid green boxes are the RMSEs of the mean of 41 estimates made using basal area factors of 4.0 to 8.0 in increments of 0.1.

Simulation 2

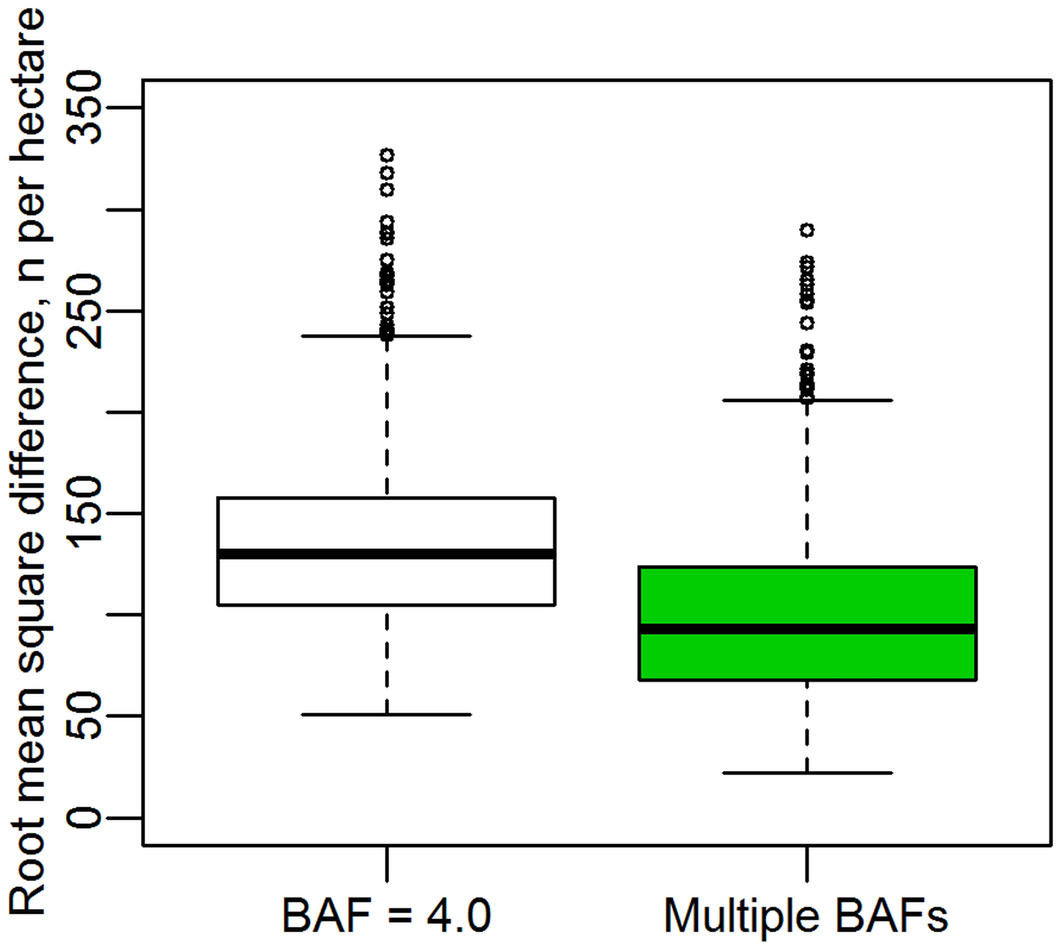

Our second simulation assumes that the “true” basal area of each randomly distributed stand is unknown, as the extent of the stands is undefined. The test thus examines the ability of models constructed using basal area estimates across two measurement years to predict the estimates (made from the same point) in the following two years. For a stand with 784 stems per hectare, across 1000 trials models constructed with the BAF = 4.0 estimates had a mean root mean square difference of 134 stems per hectare, while the Multiple BAF method yielded a mean root mean square difference of 99 stems per hectare (Fig. 3). A Wilcoxon signed rank t test showed the difference to be highly significant, with p < 2.2e-16.

Fig. 3 - Comparison of the apparent error in models relying on estimates of basal area to estimate stem density. Boxes show the root mean square difference between models constructed using two consecutive years of data with those using the next two consecutive years.

If the angle-count estimates of basal area were assumed to be “true measurements”, this would seem to imply that models constructed based on eqn. 1 have serious flaws. The error of course is not in the equation or in the model fitting, but in the inconsistency of the estimates of stand basal area in each time period. This problem is shown in Fig. 3 to be less acute when the mean of multiple basal area estimates is used.

NFI

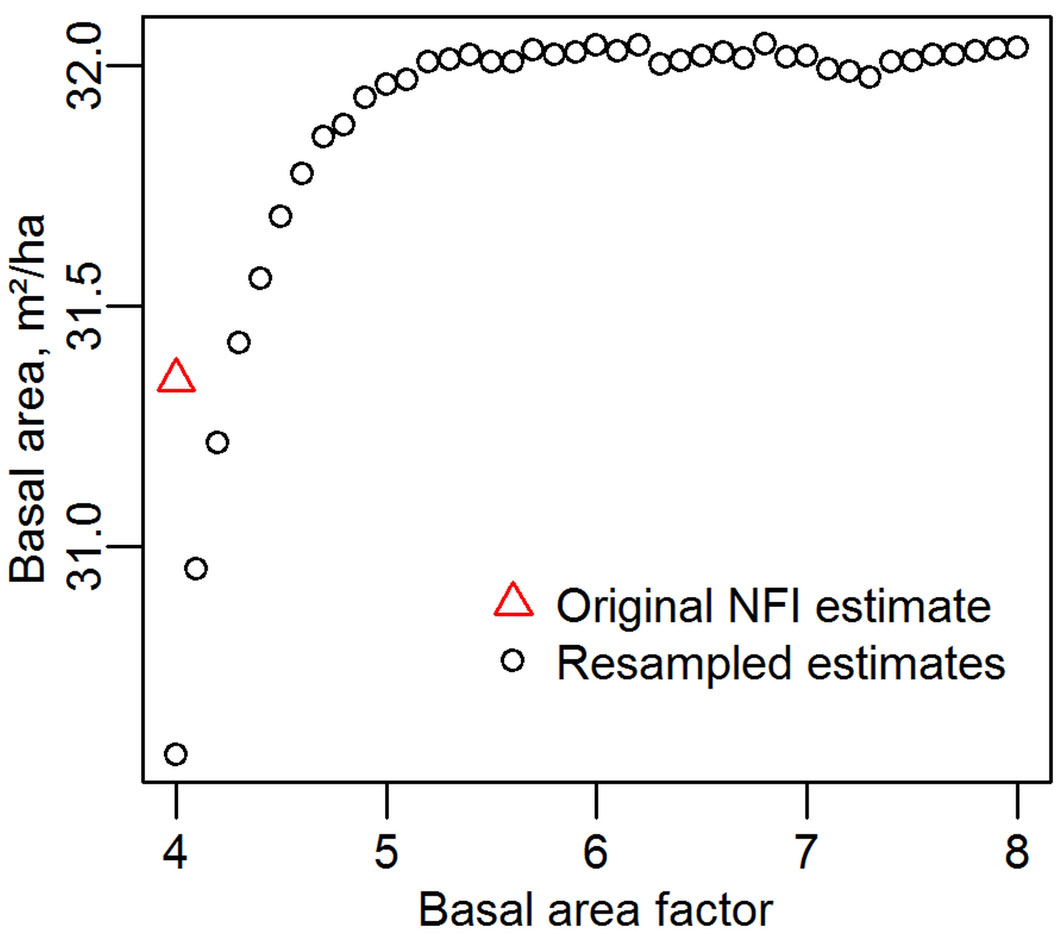

The estimates using BAFs from 4.0 to 8.0 of mean national basal area across all periods are shown in Fig. 4. Contrary to theory the aggregated estimates from all BAFs are not the same; below a BAF of around 5.0 the estimate is lower with progressively lower BAFs. Calculating mean basal area from the original (not resampled) database gives a higher estimate than with a resampling at BAF = 4.0, as some trees appear to be at a distance too great to allow their inclusion. This is because trees near the borderline are checked and their inclusion in the sample determined according to their dbh measured with calipers held at right angles to the relascope. The recorded dbh in the database however is made according to standard forestry practice - on slopes of greater than 5° the measurement is made in the cross-slope direction (operator stands directly up-hill of the tree). Presumably there are also trees that are excluded from the dataset because their “right angle” dbh is too small, but (if it was measured) their “cross slope” dbh would be sufficient to count them “in” the sample.

Basal areas calculated with the recorded dbh data will omit those trees whose recorded dbh appears too small for inclusion, but were included due to their (unrecorded) right angle dbh, explaining why the resampled BAF = 4.0 estimate is lower than that derived from the original database. At larger BAFs, the resampling includes trees that have ellipticity such that their right angle dbh would exclude them from the sample if it had been made according to standard procedure, but only in cases of extreme ellipticity would trees be potentially excluded. Assuming that no trees were inadvertently missed in the original sample, the overestimation at the larger BAFs is in the order of 2% of basal area.

Tab. 1 shows the mean estimated basal area across all plots and all periods. As suggested by Fig. 4, the multi-BAF mean is slightly above that calculated with a BAF of 4 using the original, not resampled database. Basal area estimates using multiple BAFs are overall correlated with those from the unresampled data (r = 0.95), but on individual plots substantial differences are apparent. The differences may range from half to double the original estimate.

Tab. 1 - Summary details of basal area, increment and plotwise increment variance. (n/a): not applicable.

| Parameter | NFI original |

MultiBAF mean |

Starting Value method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean basal area, periods 3 to 7 | 31.4 | 31.89 | n/a |

| Mean increment per period | 4.37 | 4.54 | 4.34 |

| Mean plotwise variance in increment | 22.68 | 11.03 | 5.47 |

| Increment, periods 3 to 4 | 3.8 | 4.27 | 4.18 |

| Increment, periods 4 to 5 | 4.02 | 4.35 | 4.29 |

| Increment, periods 5 to 6 | 5.23 | 5.06 | 4.75 |

| Increment, periods 6 to 7 | 4.39 | 4.48 | 4.11 |

Increments calculated based on the resampled data are around 4% higher than that derived from the non-resampled data calculated either with the Difference or Starting Value measurements, which give almost identical results (Tab. 1). This appears to be largely the result of random variation, as the breakdown of increment estimates per period (Tab. 1, lines 4 to 7) does not show a consistent relationship between methods.

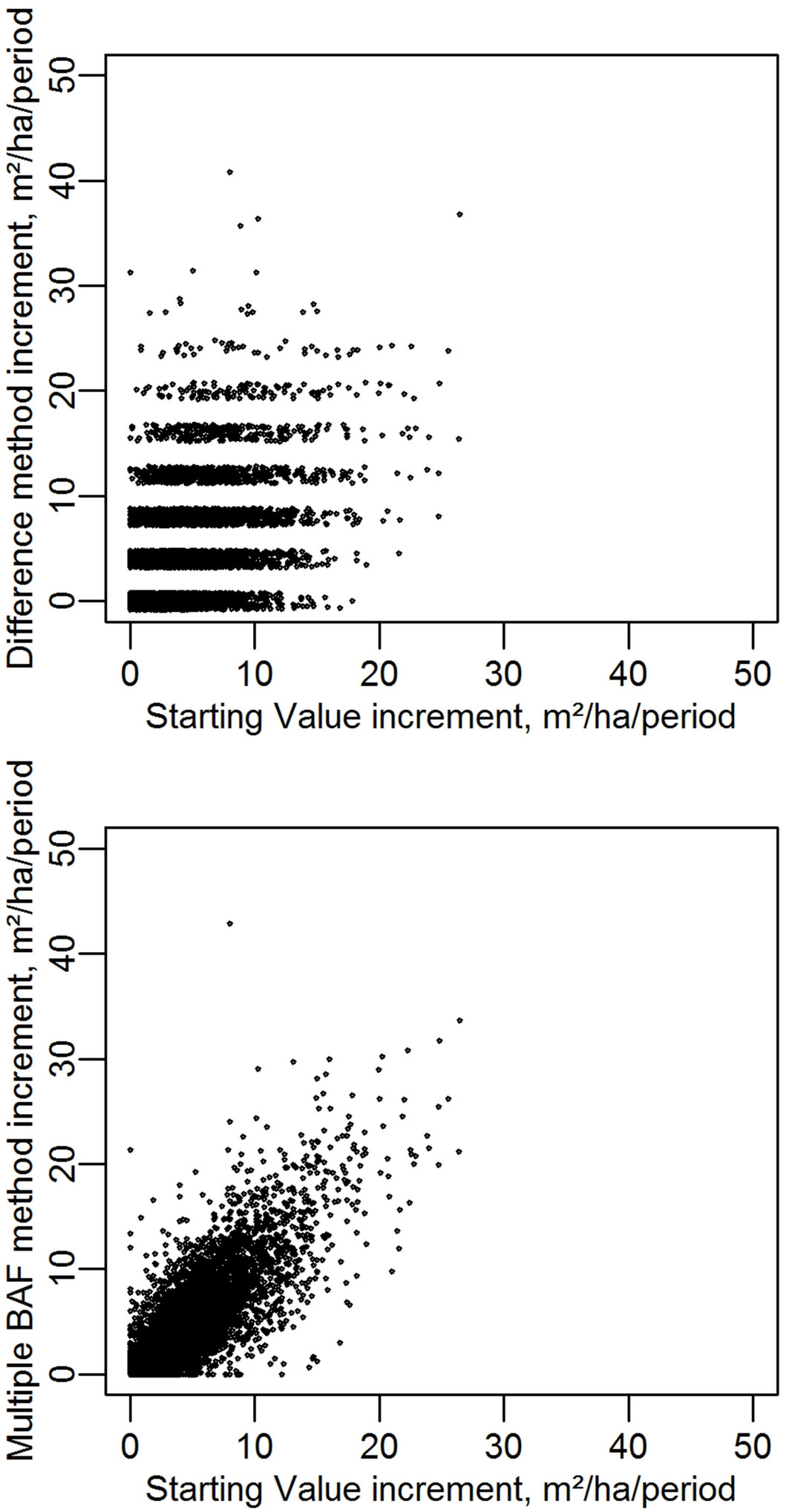

When broken down further to the level of individual plots and periods, the different methods give remarkably different estimates of increment (Fig. 5). Estimates made with the non-resampled data using the Difference method are completely uncorrelated with estimates using the Starting Value method. The mean from multiple BAFs shows correlation to the Starting Value estimates with an r of 0.91.

Fig. 5 - Per-period increment estimates using three methods (Starting Value, Difference and MultiBAF mean). For graphical purposes the Difference method results have a minor random component added, true values are all in integer multiples of 4.0. Each data point represents one of four increment periods on one of 1915 NFI plots.

The variance of the increment estimates on each plot were calculated across the five periods. The “mean plotwise variance” values in Tab. 1 are the mean of these variances, across the 1915 plots. The multiple BAF method reduces the increment variance by over 50%, indicating that these increments are derived from substantially better estimates of basal area. Although the Starting Value method provides the best increment estimates, these are not useful in estimating basal area.

Discussion

The improvements in per-point basal area estimation we claim in this study cannot be directly proven, but better estimates of increment calculated with the Difference method must come from better estimates of basal area, as only those estimates of basal area are used to estimate the increment. It is not possible to assess how close the various estimates are to a “true” value, because no true value exists; basal area is a measure of density that on single angle count plots pertains to no definable area. If multiple samples are made within a defined area then the mean of those estimates may be assessed against a known true density, but this is not useful if the desired information is an estimate of basal area surrounding individual points.

The examples we have presented in this paper show clear advantages of using a multiple BAF mean when examining individual plots. At first glance this seems counter-intuitive: the resampled values at higher BAFs are simply nested subsets of the original data, and thus seemingly should confer no increase in precision. In the context of the broader inventory this is of course true; the original (smallest) BAF gives the largest sample sizes and thus the greatest precision across the entirety of the sampled area. At the individual plot level however, the precision of the estimate is both indeterminate (because there is no defined area) and limited by the fact that the density estimate must be in integer multiples of the basal area factor. The new information gained from the resampling emerges from the knowledge that certain trees would be in the sample with a basal area factor of 4.0, but not in the sample with a BAF of some greater value. There is no issue of “pseudoreplicating” ([15]) because we at no time treat our 41 replicates as independent values. Our method relies on knowing the distance from the plot centre to each tree originally sampled (and then simulating larger BAFs), but multiple estimates could also be made in the field using different BAFs and without measuring distances.

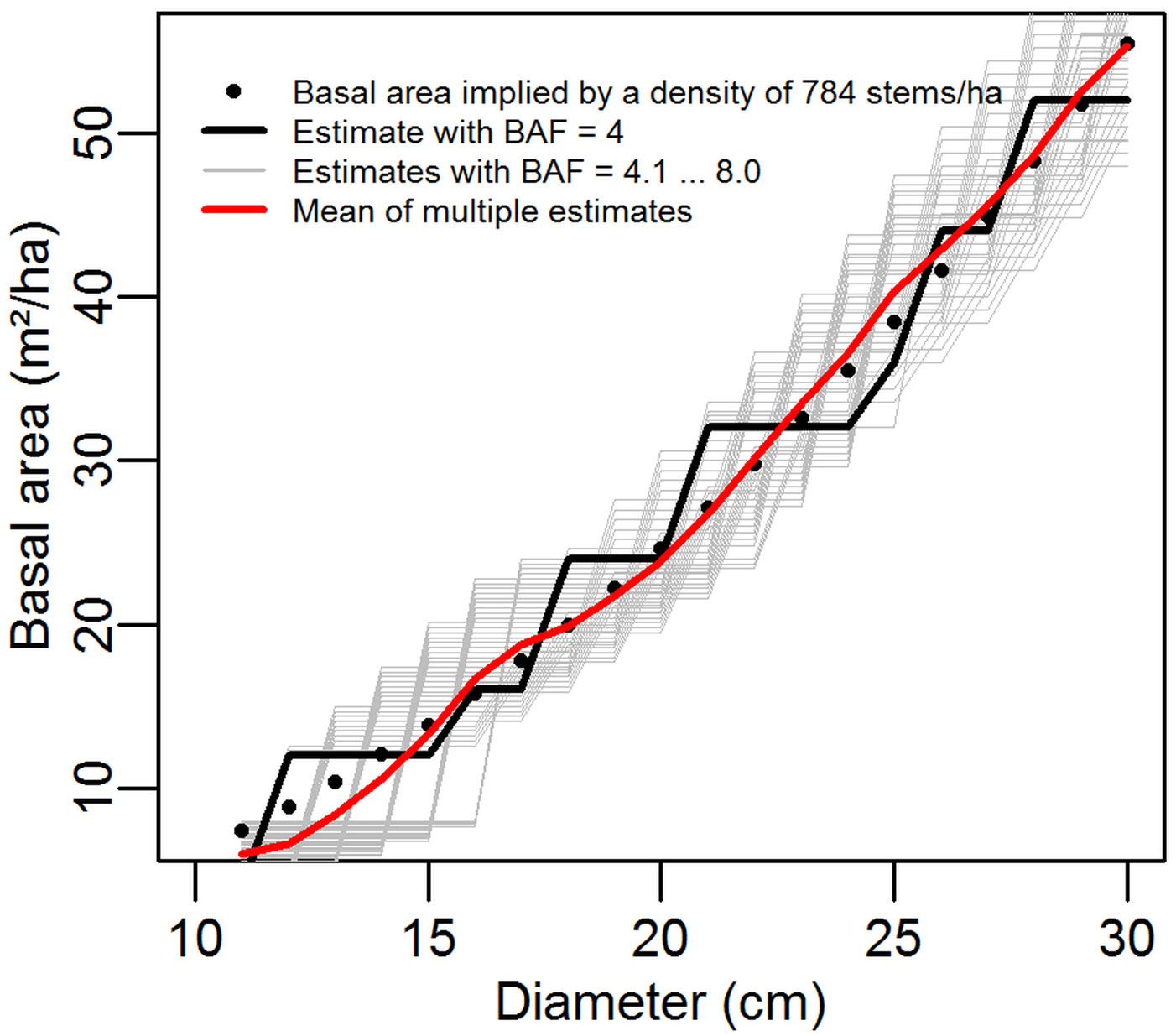

Regardless of the estimate variance in an individual angle count sample, a certain degree of error will almost certainly be present because we are estimating a continuous variable (the basal area) with a discrete function (the tree count). This is clearly shown in Fig. 6, where the estimates made with individual BAFs (the thin grey lines) can each be seen to be unbiased estimators of the basal area, but with poor precision at most single points in time. The combination of multiple BAF estimates “smooths” the steps in basal area, and thus the combined estimate (at a single time point) is closer to the true value.

Fig. 6 - Example of basal area estimates made with various basal area factors in a regular plot of 784 stems per hectare. Data is drawn from Simulation 1, with a plot centre at coordinate (1, 1).

Regardless of the basal area factor applied, the estimates are unbiased (statistically expected results are equal, even if the estimates themselves are not) so for all estimates E(G1) = E(G2) = ... E(Gn) even when G1 ≠ G2. This does not require statistical independence between the various estimates. Because the expectations are equal, as the number of estimates is increased the mean of the estimates approaches the true mean. This is illustrated in Fig. 6, drawn from our first simulation with a stem density of 784 stems per hectare and a plot centre coordinate of (1, 1).

Holgate ([12]) gives the estimate variance of a single angle count VarEST(G) as GK, which requires knowledge of the true basal area. Given the imprecision in G, using its value as an estimate of the true G is unlikely to give useful variance estimates. Whatever the individual values may be however, the combined estimate variance will be the sum of the individual estimate variances, plus twice the covariance, divided by the square of the number of estimates. For the simple case of two estimates (eqn. 2):

If the two basal area estimates are made with basal area factors K1 and K2, then (eqn. 3 and eqn. 4):

Although a general expression relating the covariance to the basal area factors cannot be determined, the results of this study show that this condition can be met.

It must be stressed that we do not claim to improve overall inventory estimates. In the case of Fig. 6, if such a sample was part of a large-scale inventory then it would be aggregated with many other (similar) samples. Although all individual samples would display the same “stepwise” increments in basal area estimation, if the sample locations were randomly located these steps would occur in different measurement years, and over a large number of samples the mean would approach a smooth curve. Our interest in this paper is how the stepwise artifact may be reduced on individual points.

If we define an area and take several samples inside that area (with fixed plots or angle counts) we can estimate the parameters of the population, and test those estimates against the truth of the population (if we know it). Using multiple BAFs does not help with this; better results are gained with larger sample sizes (i.e., the smallest BAF). The multiple BAF method cannot help us to reduce the number of samples needed to estimate a population value of basal area. Indeed, across several points, the sample variance is higher using the multiple BAF estimates. Just because we have more precise point estimates does not mean we can better estimate population values. As an example, consider a forest made up of 4 different equal-size stands, with true densities of 10, 20, 30 and 40 m2 ha-1. The whole forest thus has an average basal area density of 25 m2 ha-1. Angle counts in each stand with a BAF of 4.0 might (hypothetically) suggest 12, 12, 32 and 44 m2 ha-1, for an average of 25 and a sample variance of 249. Our multiple BAF method might give us estimates of 9, 15, 34 and 43 m2 ha-1, which makes an average of 25.25 and a sample variance of 254. If we are interested in estimating the forest population density, then the best results come from the BAF=4.0. However, if our interest is in the individual stands, then we look at the root mean square error of the individual estimates. The RMSE of the BAF=4.0 estimates is 4.69, and the RMSE of the multiple BAF estimates is 3.57. So, in applications where we treat individual points as representing reality we should use the multiple BAF estimate. Wherever we treat individual points only as samples from a population we should use the original data.

Our second simulation shows the risks in assuming that individual angle-counts comprise individual “measurements” of basal area. The “model” we use for estimating stem density (eqn. 1) is mathematically perfect, it is simply the estimated basal area per hectare divided by the individual basal area of the (identical) trees sampled. The apparent errors in the model arise from the imprecision of the input estimates, both in the calibration and validation phases. Improving these estimates clearly improves the apparent precision of the model. If such an exercise were conducted using fixed area plots the results would be trivial: with no regeneration or mortality the number of stems within the plot remains constant. Naturally, if a forest monitoring programme were to be designed with the purpose of determining precise individual plot values, then fixed-area plots would be required, but the main purpose of National Forest Inventories is the efficient estimation of forest-wide attributes, not individual plot values. The angle count method is popular in many jurisdictions because of its proven greater efficiency in estimating basal area and timber volume over large areas ([25]), but this does not mean we cannot extract other useful information if we understand its limitations.

Conclusions

The lack of precision in per-plot basal area estimates from angle-count inventories reduces the utility of these datasets in ecological applications, but improvement over the raw data is possible. Basal area or attributes directly derived from this (e.g., stem number per hectare, standing volume, biomass, stand density index) are common inputs to ecological and other models, and our reduction in random error represents a significant advance. The resampling procedure that we propose here reduces the basal area increment variance on individual inventory plots in the Austrian NFI by over 50%.

Considering the fact that permanent forest inventories based on angle count sampling theory have been established for repeated observations to assess forest changes over time (e.g., change in silvicultural approach, the role of forests for carbon mitigation issues, etc.) the reduction of the variance for derived estimates is important for the enhancement and interpretability of such inventories. We demonstrate that as increments are calculated as the difference between basal area estimates over time, the reduction in increment variance is a result of improved estimation of basal area viewed from individual points. In cases where stand basal area or one of its derivatives is used as an independent variable, this improvement in precision is certain to increase the usefulness of large-scale NFI data derived from angle-count methods in many applications.

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the project “Comparing satellite versus inventory driven carbon estimates for Austrian Forests” (MOTI). We are grateful for the financial support provided by the Energy Fund of the Federal State of Austria - managed by Kommunalkredit Public Consulting GmbH under contract number K10AC1K00050. The Austrian NFI data for this study was generously provided by the Austrian Bundesforschungs- und Ausbildungszentrum für Wald, Naturgefahren und Landschaft (BFW). We thank Dr. Klemens Schadauer of the BFW and Prof. Hubert Sterba of the Institute of Forest Growth and Yield Research at BOKU University for their pre-submission reviews of this manuscript.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Hubert Hasenauer

Institute of Silviculture, Department of Forest and Soil Sciences, BOKU University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Peter Jordan Str. 82, A-1190 Wien (Austria)

School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, PO Box 157, NSW 2480 Lismore (Australia)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Eastaugh CS, Hasenauer H (2014). Improved estimates of per-plot basal area from angle count inventories. iForest 7: 178-185. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1158-007

Academic Editor

Marco Borghetti

Paper history

Received: Oct 22, 2013

Accepted: Jan 29, 2014

First online: Feb 17, 2014

Publication Date: Jun 02, 2014

Publication Time: 0.63 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2014

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 56053

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 46578

Abstract Page Views: 2969

PDF Downloads: 4956

Citation/Reference Downloads: 38

XML Downloads: 1512

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 4395

Overall contacts: 56053

Avg. contacts per week: 89.28

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2014): 3

Average cites per year: 0.25

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Review Papers

Integration of forest mapping and inventory to support forest management

vol. 3, pp. 59-64 (online: 17 May 2010)

Research Articles

Comparing land use registry and sample based inventory to estimate forest area in Podlaskie, Poland

vol. 10, pp. 315-321 (online: 23 February 2017)

Research Articles

Optimizing line-plot size for personal laser scanning: modeling distance-dependent tree detection probability along transects

vol. 17, pp. 269-276 (online: 07 September 2024)

Research Articles

Methods to inventory and strip thin in dense stands of aspen root suckers

vol. 8, pp. 590-595 (online: 22 April 2015)

Research Articles

Integrating area-based and individual tree detection approaches for estimating tree volume in plantation inventory using aerial image and airborne laser scanning data

vol. 10, pp. 296-302 (online: 15 December 2016)

Commentaries & Perspectives

Benefits of a strategic national forest inventory to science and society: the USDA Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis program

vol. 1, pp. 81-85 (online: 28 February 2008)

Research Articles

The effect of the calculation method, plot size, and stand density on the accuracy of top height estimation in Norway spruce stands

vol. 10, pp. 498-505 (online: 12 April 2017)

Research Articles

Using self-organizing maps in the visualization and analysis of forest inventory

vol. 5, pp. 216-223 (online: 02 October 2012)

Research Articles

Allometric models for the estimation of foliage area and biomass from stem metrics in black locust

vol. 15, pp. 281-288 (online: 27 July 2022)

Research Articles

Estimation of aboveground forest biomass in Galicia (NW Spain) by the combined use of LiDAR, LANDSAT ETM+ and National Forest Inventory data

vol. 10, pp. 590-596 (online: 15 May 2017)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword