Effective monitoring as a basis for adaptive management: a case history of mountain pine beetle in Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem whitebark pine

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 2, Issue 1, Pages 19-22 (2009)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor0477-002

Published: Jan 21, 2009 - Copyright © 2009 SISEF

Short Communications

Collection/Special Issue: Cost Action E29 Meeting 2008 - Istanbul (Turkey)

Future Monitoring and Research Needs for Forest Ecosystems

Guest Editors: Marcus Schaub (WSL, Birmensdorf, CH)

Abstract

With reference to massive outbreaks of a variety of bark beetles occurring across the forests of western North America, it is stressed that an accurate assessment of the extent of the problem is the first step toward formulating effective adaptive management strategies. This assessment will only be possible through a coordinated effort that combines all available technologies, that is an approach that builds on satellite image analysis, aerial survey from fixed-wing aircraft, and on the ground observation and measurement.

Keywords

Mountain pine beetle, Whitebark pine, Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, Global warming, Disturbance ecology

Introduction

Massive outbreaks of a variety of bark beetles have recently, or are presently occurring across the forests of western North America. These outbreaks include the extensive die-off of piñon pine in the south west, devastating outbreaks of spruce beetle in Alaska, and unprecedented mountain pine beetle outbreaks in the U.S. and Canadian Rocky Mountains. Since all of these outbreaks involve native species, a basic question becomes differentiating between: those outbreaks that are within the range of historic variability; those that are outside the historic range of natural variability, but within the limits of ecosystem resiliency; and those that are truly a threat to continued ecosystem survival. In particular, two current outbreaks involving the mountain pine beetle most appear to fall into the last category. These are the invasive range expansion into the boreal forest, and the eruption of sustained outbreak populations in high elevation, whitebark pine forests.

Mountain pine beetle in lodgepole pine forests

During the mid 1990’s, when anthropogenic global warming was becoming an accepted fact by the mainstream scientific community, computer simulations indicated the potential for northern expansion of mountain pine beetle populations into previously unoccupied habitat, including the area of overlap between lodgepole and jack pine ([5]). It was further noted that if this occurred, overlapping pine habitat connected the entire North American continent from British Columbia to Texas. Subsequent events have corroborated these predictions ([10]). The previously impenetrable barrier of the Canadian Rockies was breached in 2003, and invading populations are now widespread in Alberta and the largest recorded MPB outbreak ever continues to expand (currently involving 13 million ha - [1]); and the hypothesized colonization of jack pine has occurred in the zone of overlap between jack and lodgepole pine (A. Carroll, personal communication). The last apparent barrier to continent-wide invasion is the long, dark, cold winter of the interior boreal forest. New quantitative tools will help anticipate the degree of climate warming required to overcome this barrier ([11]). The Canadian government has committed significant resources to address both the ecological and social issues resulting from this epic event.

Mountain pine beetle in whitebark pine forests

The second unparalleled mountain pine outbreak is occurring across the range of whitebark pine, a foundation species for high-elevation forests of the northern U.S. Rocky Mountains (Fig. 1). The ecological amenities provided by whitebark pine are far-reaching, ranging from maintaining healthy watersheds to providing critical habitat for elk, bears, birds, squirrels, and other wildlife ([10], [6]). Although mountain pine beetles are historically resident in whitebark pine, the ecological association was vastly different from that with lower-elevation lodgepole pine. Instead of being an irruptive species that co-evolved with the host, sub-marginal populations existed as a saprophyte in downed or weakened trees. Although outbreaks in whitebark pine have occurred during unusually warm periods, these have been of limited extent and duration. The climatic conditions in these high-elevation habitats were too severe for sustained outbreaks. However, increasing global temperatures has resulted in outbreak populations expanding into these previously inhospitable habitats. The result is an alarming intensification of widespread activity in vulnerable whitebark pine forests that began shortly after the turn of century (2002 or 2003). Nothing comparable to what is occurring today has been observed in recorded history or exists in the disturbance legacy of this long-lived species ([4]).

Fig. 1 - Mountain pine beetle mortality in whitebark pine. An example of the scale and intensity of mountain pine beetle mortality in whitebark pine of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. This aerial photograph was taken by Jane Pargiter during the summer of 2007. The red trees were killed by mountain pine beetle during summer of 2006, the gray trees were killed the previous summer. The few remaining green trees are probably currently infested, and will turn red the summer of 2008.

Whitebark pine in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

Nowhere is whitebark pine mortality more keenly felt than in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), a geographically large (approximately 9.000.000 ha) and administratively complex (a mix of private ownership and lands managed by the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) area that encompasses 16 major mountain ranges. The potential loss of whitebark pine in this sensitive ecosystem (Yellowstone National Park is the world’s first national park and a United Nations World Heritage Site) holds severe consequences for a number of sensitive species including the grizzly bear. By raiding red squirrel middens that contain vast quantities of whitebark pine cones, grizzlies efficiently obtain a source of high-quality food from the large, nutritious whitebark pine seeds. This food resource becomes available to the grizzly at a critical time - in the fall, just prior to entering hibernation. If female grizzlies enter hibernation when whitebark pine seed crops are poor, they produce fewer cubs. In addition, human-caused mortality rates greatly increase if whitebark pine crops fail, as grizzlies are driven to forage in lower-elevation areas where human conflicts become increasingly likely ([8], [2], [7], [9]).

Although catastrophic loss of whitebark pine in the GYE has already occurred, no one really knows its full extent. Regrettably, critical policy decisions are being made based on this inadequate information. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s 2007 document supporting delisting the grizzly bear (72 Fed. Reg. 14.866) stated that, “… (only) 16 percent of the total area of whitebark pine found in the GYA … has experienced some level of mortality due to mountain pine beetles.” It is clear that, even from the incomplete ADS data that is available, the figure is much higher (see Tab. 1). Clearly, there is a pressing need to first know the extent of the problem before rational management decisions can be made. The objective of the remainder of this contribution is to briefly describe ongoing development of a monitoring protocol designed to measure the full extent of mountain pine beetle caused mortality in whitebark pine in the GYE.

Tab. 1 - Aerial detection survey for the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, 1999-2007. Although all of the Ecosystem was not surveyed every year, the level of mortality is a clear indication of both trend and magnitude of the ongoing outbreak.

| Survey Year |

Number of Dead WBP | Infested Acres |

|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 380 | 535 |

| 2000 | 4166 | 2636 |

| 2001 | 64273 | 28322 |

| 2002 | 121278 | 49689 |

| 2003 | 288603 | 75984 |

| 2004 | 377920 | 136388 |

| 2005 | 823646 | 135597 |

| 2006 | 285490 | 147476 |

| 2007 | 637588 | 171572 |

Monitoring whitebark pine mortality

Effective monitoring of whitebark pine loss presents unique difficulties since the high mountains occupied by this species are the among most rugged, inhospitable and remote habitats on the continent. Recognizing both the pressing need for, and the unique difficulties in obtaining, accurate monitoring data; a coalition of concerned citizens and non-governmental organizations has began formulating an approach that builds on satellite image analysis, aerial survey from fixed-wing aircraft, and on-the-ground observation and measurement. Each will be briefly discussed.

Satellite image analysis

Satellite imagery directly addresses the issue of difficult terrain and remoteness. However, detecting the level of mortality has proven to be more difficult than originally anticipated. A recent description of both the difficulties and advances that have been made can be found in Hicke & Logan ([3]). Satellite image analysis is capable of providing a reliable estimate of previous year (red tree) mortality, but it seems unlikely that mortality will be measurable after the needles drop, leaving the gray stems. Additionally, satellite imagery of sufficient resolution is expensive, but not prohibitively so considering the ecological value of the resource.

Aerial detection by human observer

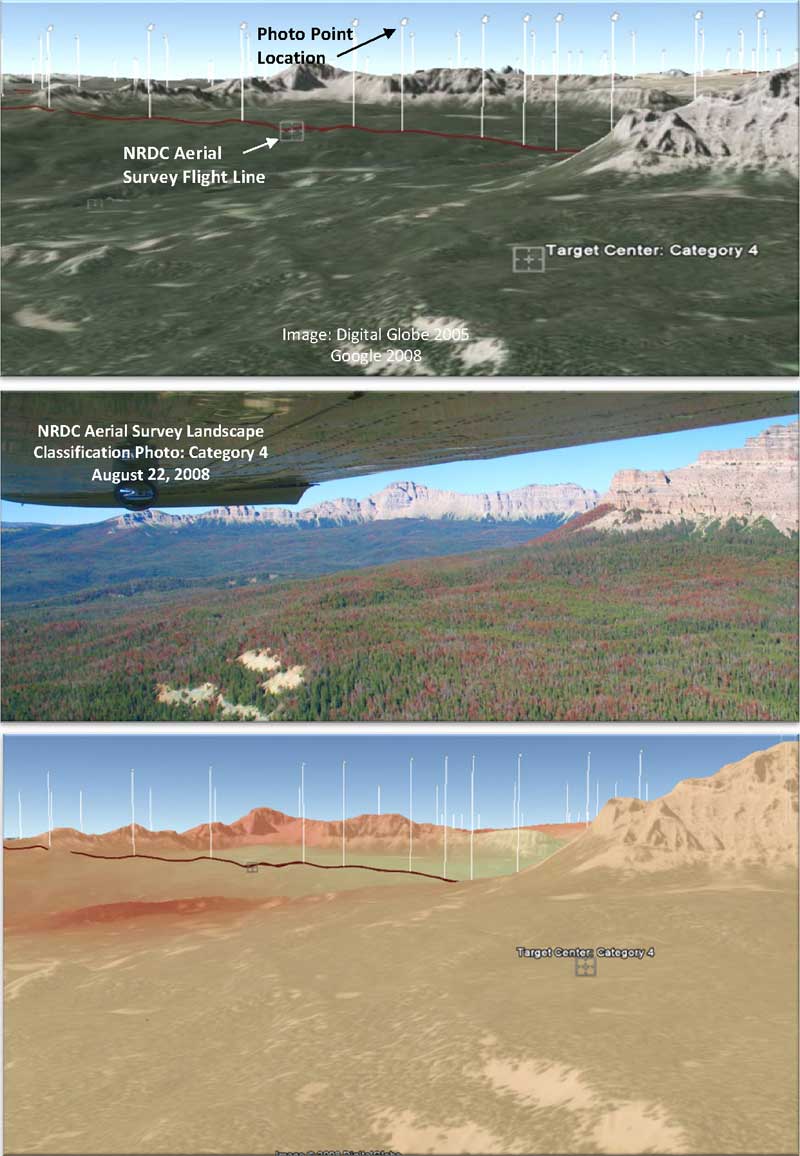

The principle measure of bark beetle activity is the USDA Forest Service’s Aerial Detection Survey (ADS) that annually measures current season forest insect mortality. Due to the broad mandate of ADS to measure all insect mortality on public lands, ADS does not routinely include designated Wilderness Areas and National Parks; and Wilderness Areas and National Parks comprise nearly 1/3 of the GYE. The distribution of whitebark pine is even more skewed, with almost 2/3 of GYE whitebark pine in either Wilderness or National Parks. ADS has also prioritized economically important timber species like lodgepole pine, and as a result, whitebark pine has been under-surveyed. Recognizing these limitations to ADS, the Natural Resource Defence Council (NRDC) funded a pilot program during summer 2008 to evaluate feasibility of an aerial survey approach specifically designed to quantify mountain pine beetle mortality in GYE whitebark pine. The technique used in this study was landscape level classification of MPB impact into six categories, ranging from zero (no mortality outside of background levels) to five (the residual forest remaining after an outbreak runs its course). The survey results were photo-documented and georeferenced using Google Earth©, and then used to generate a continuous impact map (Fig. 2). By focusing exclusively on whitebark pine distribution, and implementing a landscape classification based on the cumulative impact, this approach provided a cost-effective means to measure the integrated impact of mortality that has occurred beginning in the early 2000s. The results are encouraging, and funding is being sought to support flying the entire GYE in summer 2009.

Fig. 2 - Screen capture of Google Earth©.kml file that contains NRDC Aerial survey results. Information retrievable from the Google© screen are, flight lines, location for point of photograph (x,y,z), target center of photograph on the landscape, mortality category level, and the interpolated surface of mortality category.

On the ground evaluation

Some important ecological observations cannot be made from either satellite imagery or from aircraft flying over 200 mph at 16 000 ft. elevation. Recognizing this ecological limitation, a group of citizens most impacted by the loss of whitebark pine was organized to document the level of whitebark pine mortality across the entire ecosystem. Documentation procedures and protocols have evolved and been formalized through funding provided by NRDC. The observation by citizen scientists will be used to verify aerial detection results and to evaluate critical factors, like recruitment of seedlings and saplings, that cannot be measured through remote sensing. Citizen scientist observations will also augment results of more formal stand survey information provided by land management agencies.

Conclusion

Although important management decisions like the Grizzly Bear delisting rule illustrate the need for effective monitoring, all down-stream ecological amenities provided by whitebark pine are impacted by loss of this foundation species. Accurately accessing the extent of the problem is the first step toward formulating effective adaptive management strategies, and this assessment will only be possible through a coordinated effort that combines all available technologies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Natural Resource Defense Council for generous support for much of this work, and ESRI for supplying JAL a conservation copy of ArcMAP and associated GIS software.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

P.O. Box 482, Emigrant, MT 59027 (USA)

GeoGraphics Inc., 90 W Center St., Logan, UT 84321 (USA)

Natural Resources Defense Council, Box 70, Livingston, MT 59047 (USA)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Logan JA, Macfarlane WW, Willcox L (2009). Effective monitoring as a basis for adaptive management: a case history of mountain pine beetle in Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem whitebark pine. iForest 2: 19-22. - doi: 10.3832/ifor0477-002

Academic Editor

Marcus Schaub

Paper history

Received: Mar 13, 2008

Accepted: Dec 09, 2008

First online: Jan 21, 2009

Publication Date: Jan 21, 2009

Publication Time: 1.43 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2009

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 61043

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 51583

Abstract Page Views: 3826

PDF Downloads: 4570

Citation/Reference Downloads: 82

XML Downloads: 982

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 6230

Overall contacts: 61043

Avg. contacts per week: 68.59

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2009): 15

Average cites per year: 0.88

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Amount and distribution of coarse woody debris in pine ecosystems of north-western Spain, Russia and the United States

vol. 7, pp. 53-60 (online: 28 October 2013)

Research Articles

Allometric equations to assess biomass, carbon and nitrogen content of black pine and red pine trees in southern Korea

vol. 10, pp. 483-490 (online: 12 April 2017)

Research Articles

Long-term changes in surface-active beetle communities in a post-fire successional gradient in Pinus brutia forests

vol. 10, pp. 376-382 (online: 16 March 2017)

Research Articles

A bark beetle infestation predictive model based on satellite data in the frame of decision support system TANABBO

vol. 13, pp. 215-223 (online: 06 June 2020)

Research Articles

Influence of soil and topography on defoliation intensity during an extended outbreak of the common pine sawfly (Diprion pini L.)

vol. 10, pp. 164-171 (online: 19 November 2016)

Research Articles

Determination of differences in temperature regimes on healthy and bark-beetle colonised spruce trees using a handheld thermal camera

vol. 14, pp. 203-211 (online: 02 May 2021)

Research Articles

Distribution and habitat suitability of two rare saproxylic beetles in Croatia - a piece of puzzle missing for South-Eastern Europe

vol. 11, pp. 765-774 (online: 28 November 2018)

Research Articles

Ecological and anthropogenic drivers of Calabrian pine (Pinus nigra J.F. Arn. ssp. laricio (Poiret) Maire) distribution in the Sila mountain range

vol. 8, pp. 497-508 (online: 10 November 2014)

Research Articles

Climate impacts on tree growth in a Neotropical high mountain forest of the Peruvian Andes

vol. 13, pp. 194-201 (online: 19 May 2020)

Research Articles

Growth patterns of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) under the current regional pollution load in Lithuania

vol. 8, pp. 509-516 (online: 12 November 2014)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword