Impact of management practices on habitat use by birds in exotic tree plantations in northeastern Argentina

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 19, Issue 1, Pages 38-44 (2026)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor4742-018

Published: Feb 06, 2026 - Copyright © 2026 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Bird habitat use can be influenced by the structural complexity of exotic plantations. Management practices such as pruning and thinning can promote understory development, increasing structural complexity and enhancing ecosystem integrity. Given the rapid expansion of fast-growing tree species, understanding bird responses to different forestry practices is crucial for sustainable management. In northeastern Argentina, we assessed bird habitat use, including trophic guild composition, behavioral patterns, and strata use across native forests and exotic Pinus and Eucalyptus plantations managed to promote or limit understory development. Using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS), hierarchical cluster analysis, and PERMANOVA, we evaluated differences in bird assemblages among these forest types. Our results indicate that plantations with developed understory exhibit habitat use patterns more similar to native forests; however, certain ecologically important species, such as large fruit dispersers, were absent. Among plantation types, Pinus plantations with understory development were the most comparable to native forests in strata use and behavior categories. Birds in both native forests and plantations with developed understory used all available strata and were abundant in the shrub layer, including insectivorous and insectivorous-frugivorous species, whereas plantations lacking understory were functionally similar, exhibiting reduced diversity in trophic guilds. Although Eucalyptus plantations showed greater functional differences from native forests than Pinus plantations, the variation within Eucalyptus plantations based on management practices was particularly striking. We found that although plantations with developed understory cannot fully replicate the ecological functions of native forests, they can mitigate habitat simplification impacts by supporting similar but less abundant trophic guilds with comparable strata use and behaviors. As the demand for exotic plantations increases, effective management practices will become essential for maintaining biodiversity and promoting sustainable land use. Practices such as regular thinning and the establishment of mixed-species plantations can help better replicate the functional roles of native forests, thereby maintaining biodiversity and promoting sustainable land use.

Keywords

Forest Management Practices, Understory, Trophic Guilds, Pinus, Eucalyptus, Sustainable Management

Introduction

The management plans of forest plantations vary with the intended end products and are among the variables that affect wildlife responses ([25]). For plantations aimed at sawn timber production, management practices focus on maximizing wood quality and growth through pruning and thinning. Pruning consists of removing branches to produce knot-free wood, while thinning reduces tree density per hectare to concentrate growth on selected individuals ([11]). In contrast, plantations for cellulose pulp production prioritize higher tree densities, and intermediate thinning is not carried out.

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of maintaining understory vegetation and structural complexity in managed forests and plantations to support biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. For example, insectivorous bats benefit from pine plantations with well-developed understory layers, as these habitats provide increased foraging opportunities and support species richness, including rare and endangered taxa ([1]). Similarly, in agricultural landscapes, maintaining understory vegetation in oil palm plantations has been shown to enhance populations of beneficial insects such as assassin bugs, which play a key role in pest control ([42]). Additionally, the presence of understory vegetation in smallholder oil palm plantations has been linked to increased butterfly abundance, underscoring the role of habitat complexity in sustaining diverse insect communities ([22]). These findings emphasize that understory management can significantly influence wildlife assemblages across different ecosystems, reinforcing the need to integrate understory conservation into forestry and agricultural practices to promote biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Avian responses to plantations are often assessed through presence and abundance ([31], [29], [32]) or by comparing different plantation growth stages ([4]). However, fewer studies examine how birds use plantations and rarely consider the effect of different management practices. Among studies on habitat use in plantations, Ramírez-Mejía et al. ([39]) compared understory bird use in native forests and Eucalyptus plantations in Colombia by counting bird records in each habitat. However, they did not categorize how birds use plantations (e.g., nesting, foraging, roosting) nor consider different forest management practices. On the other hand, some studies have documented raptors nesting in Eucalyptus plantations and highlighted the importance of plantation vegetation structure and management practices that promote bird habitat use ([19], [41]).

This study aims to evaluate and compare how birds use habitat in native forests (as a reference habitat unit), and two types of plantations (Pinus spp. and Eucalyptus grandis) managed under different practices: pruning and thinning vs. no pruning. These practices determine whether plantations develop understories. Specifically, we assess (i) how birds use different forest strata (arboreal, shrub, and herbaceous), (ii) analyze the composition of trophic guilds, and (iii) behavioral patterns across native forests and plantations with different management practices. This allows us to determine whether similar plantation physiognomies lead to similar habitat-use patterns, or whether birds exhibit distinct responses based on plantation type and management.

Based on the hypothesis that bird assemblage structure is influenced by habitat complexity, our predictions to test are that (i) habitat use by birds varies between native forests and exotic plantations, and this variation is due to differences in vegetation structure; and (ii) intrinsic differences between pine and eucalyptus, combined with forest management practices, distinctly affect bird habitat use. Unlike previous studies focusing on species presence and abundance, we integrate functional aspects of habitat use, providing a more detailed understanding of how birds interact with managed forests. The results can inform strategies to promote bird habitat use and can be adopted as more environmentally friendly practices, benefiting both biodiversity and forestry companies (e.g., certifications).

Methods

Study area

The study was conducted in the northeast of the Corrientes province, Argentina, in the field lands of the Grupo Las Marías (28° 06′ 45″ S, 56° 03′ 04″ W). These lands cover 31.000 ha in the Campos District of the Paranaense Phytogeographic Province ([10]), also known as the Campos and Malezales Ecoregion ([9]). The climate is subtropical, with an annual precipitation of 1794 mm in the study area. The natural vegetation consists of a mosaic of grasslands, pastures, and patches of forests dominated by Myracrodruon balansae and Helietta apiculata, along with riparian forests of Parapiptadenia rigida and Nectandra angustifolia. The main productive activities in the area include yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) and tea (Camellia sinensis) cultivation, pine (Pinus spp.) and eucalyptus (Eucalyptus spp.) plantations, and extensive livestock farming.

The eucalyptus plantations cover an area of around 1288 ha, primarily consisting of Eucalyptus grandis, while the pine plantations cover an area of 6479 ha, mainly composed of Pinus elliottii and Pinus taeda ([17]). Both types of plantations comprise stands with management conditions of thinning and no thinning, which determine different tree densities and contrasting understory development. The density of trees in plantations without developed understory ranges from 460 to 600 trees ha-1, compared to stands with developed understory, which have less than 400 trees ha-1 (Grupo Las Marías, personal communication). Pines at the study site are harvested between 18-20 years old, while faster-growing eucalyptus are harvested at 12-15 years of age ([17]).

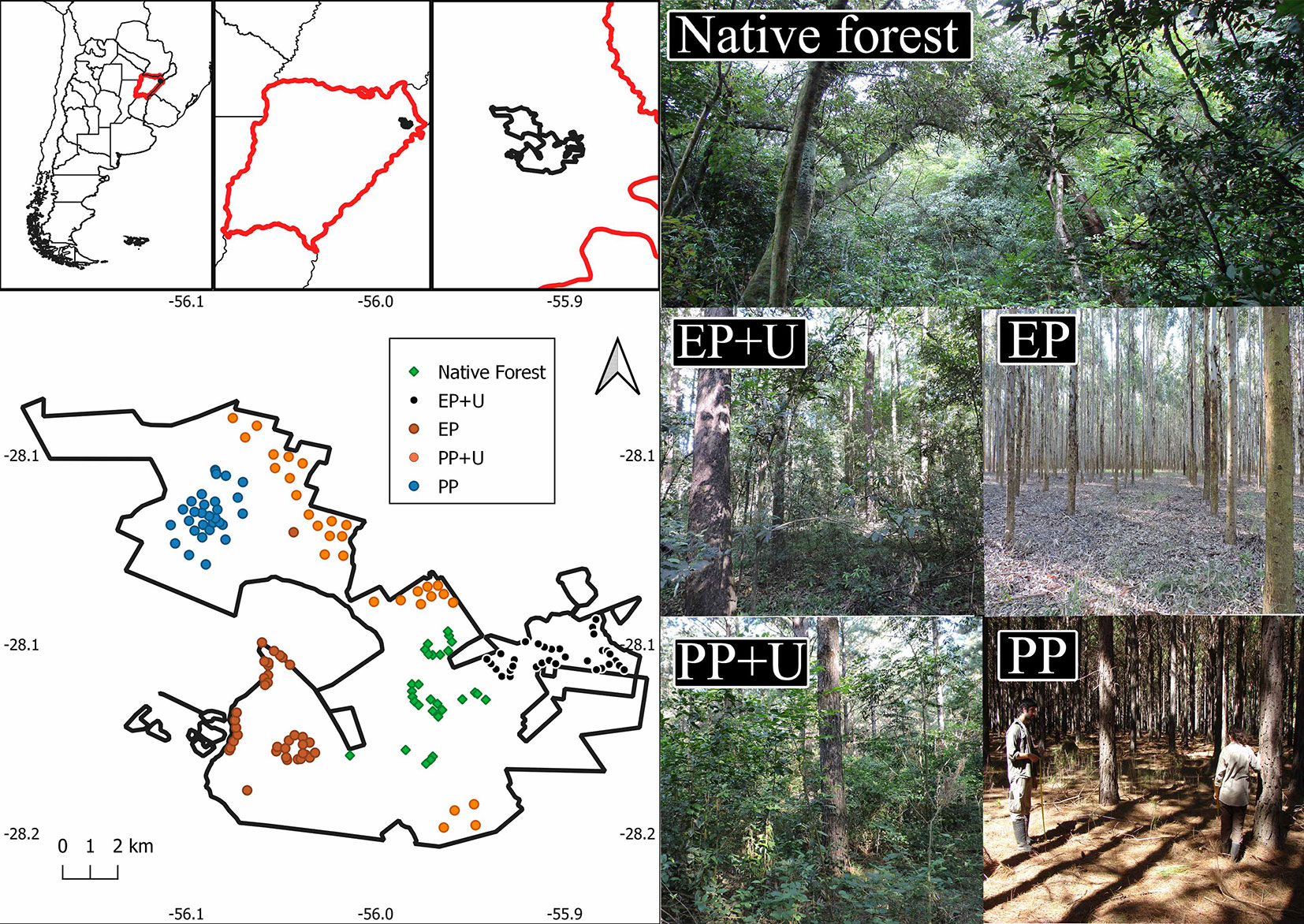

Bird survey

We selected plantation stands and native forest patches that met the study requirements for area, vegetation structure, and plantation age. We established five habitat units: pine plantation with developed understory (PP+U), pine plantation without developed understory (PP), eucalyptus plantation with developed understory (EP+U), eucalyptus plantation without developed understory (EP), and native forest (NF - Fig. 1). A total of 154 bird surveys were conducted between spring 2014 and summer 2016, using the point count method ([7]). Birds seen and heard within a 50 m radius were recorded for 10 minutes from sunrise and for the following four hours, always in good weather conditions. The counting points were spaced 250-300 m apart to ensure data independence and were located 50 m from the edge of the habitat unit to avoid edge effects.

Fig. 1 - Location of the study area in northeastern Argentina and location of survey points, with examples of the different habitats. (NF): native forest; (EP+U): eucalyptus plantation with developed understory; (EP): eucalyptus plantation without developed understory; (PP+U): pine plantation with developed understory; (PP): pine plantation without developed understory.

Bird species were assigned to trophic guilds based on their main diet component and foraging strategy, using a combination of our field observations and bibliographic data on bird feeding ecology in the region ([34], [26], [2], [5], [15], [14]). Behaviors were recorded during field surveys and grouped into seven functional categories: resting/standing, moving (flying, walking, hopping), nesting, courtship, vocalization, agonistic, and foraging. For each bird, we assigned the behavior first detected at the time of observation. Systematic ordering of bird species follows Remsen et al. ([40]).

The sampling effort was similar for every habitat and ranged from 26 to 32 point counts per habitat, which guaranteed the consistency of the data collected (Tab. 1). To verify the robustness of our comparisons, we assessed species inventory completeness using sample coverage as a measure of completeness ([13]), using rarefaction based on sample size and extrapolation with Hill numbers or the effective number of species (q=0). All habitat units had high species inventory completeness, ranging from 90.1% to 97.6%. (Tab. 1).

Tab. 1 - Number of point counts, total and relative abundance, and sample completeness in five environments in northeastern Argentina. (NF): Native forests; (EP+U): eucalyptus plantation with developed understory; (EP): eucalyptus plantation without developed understory; (PP+U): pine plantation with developed understory; (PP): pine plantation without developed understory.

| Habitat | Samples | Abundance | Sample coverage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mean | SD | Median | |||

| NF | 29 | 280 | 9.7 | 4.7 | 10 | 96.4 |

| EP+U | 26 | 120 | 4.7 | 3.9 | 3 | 90.1 |

| EP | 26 | 19 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1 | 90.9 |

| PP+U | 32 | 245 | 7.7 | 4 | 7 | 97.6 |

| PP | 31 | 55 | 2 | 1.2 | 2 | 91.4 |

We performed a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA - [3]) to test whether strata use, trophic guild composition, and frequency of behavior types differ among plantation practices (PP+U, PP, EP+U, and EP) and native forests. PERMANOVA allows comparisons of multivariate ecological community data across different sampling intensities and does not rely on assumptions of normality or homoscedasticity. A post hoc analysis was performed across the different habitat units. The error rate due to the high number of comparisons was controlled using the false discovery rate method ([6]). To visualize the similarities among the five types of habitats, we performed non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS - [28]), including all response variables to reduce the dimensionality of the data. We selected a three-axis solution because the lowered final stress was < 0.1, indicating a good fit. We performed hierarchical cluster analysis using the average linkage method based on Euclidean distances calculated from the variables: stratum use, trophic guild composition, and behavior frequency. This clustering approach groups the habitat types into a dendrogram based on their overall functional similarity, providing a visual representation of the relationships among the communities. Type I error was set at 0.05. All analyses and data visualization were performed using R v. 3.5.3 software ([38]) and the packages “Inext” ([24]), “vegan” ([36]), and “ggplot2” ([44]).

Results

We registered 719 records from 63 bird species. The mean bird abundance per count point was highest in the native forest, followed by EP+U. The lowest mean bird abundance was recorded in EP (Tab. 1). Functional bird groups used different strata across habitat units. The understory of native forests and plantations with a developed understory was mainly used by the insectivorous guild (IF), which was almost absent in plantations without a developed understory (Tab. 2).

Tab. 2 - Frequency of records of trophic guilds by stratum (s: shrub; t: tree; h: herbaceous) in each habitat. Trophic guilds - (CC): Carcass-eating, perch-based, aerial, and terrestrial carnivores (scavengers); (PC): Perch or aerial carnivores; (GS): Ground granivores; (IA): Aerial insectivores; (IF): Foliage-gleaning and probing insectivores; (IFR): Foliage-gleaning and probing insectivore-frugivores; (IFS): Ground-dwelling foliage-gleaning and probing insectivore-frugivores; (IO): Perch-based insectivore-omnivores with fluttering and pursuit; (TI): Trunk insectivores; (NI): Nectar-feeding, hovering insectivores; (OP): Omnivores with pecking and probing of ground, foliage, and trunks. Habitat abbreviations are detailed in Tab. 1.

| Guild | Native Forest | EP+U | EP | PP+U | PP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | t | h | s | t | h | t | s | t | h | s | t | |

| CC | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | 6 | - | - | 4 |

| PC | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 5 | - | - | 4 |

| GS | 3 | 6 | - | - | 3 | - | 5 | - | 28 | - | - | 11 |

| IA | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| IF | 74 | 24 | 16 | 31 | 10 | 7 | - | 60 | 8 | 14 | 1 | - |

| IFR | 19 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 6 | - | 6 | 14 | 6 | - | - | 12 |

| IFS | 2 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 10 | - | - | 31 | 18 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| IO | 4 | 21 | - | 2 | 11 | - | 2 | 3 | 28 | 1 | - | 4 |

| TI | 3 | 1 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 5 |

| NI | 11 | 3 | - | 1 | 10 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 2 | - |

| OP | 2 | 20 | - | - | 4 | - | 1 | - | 5 | 1 | - | 3 |

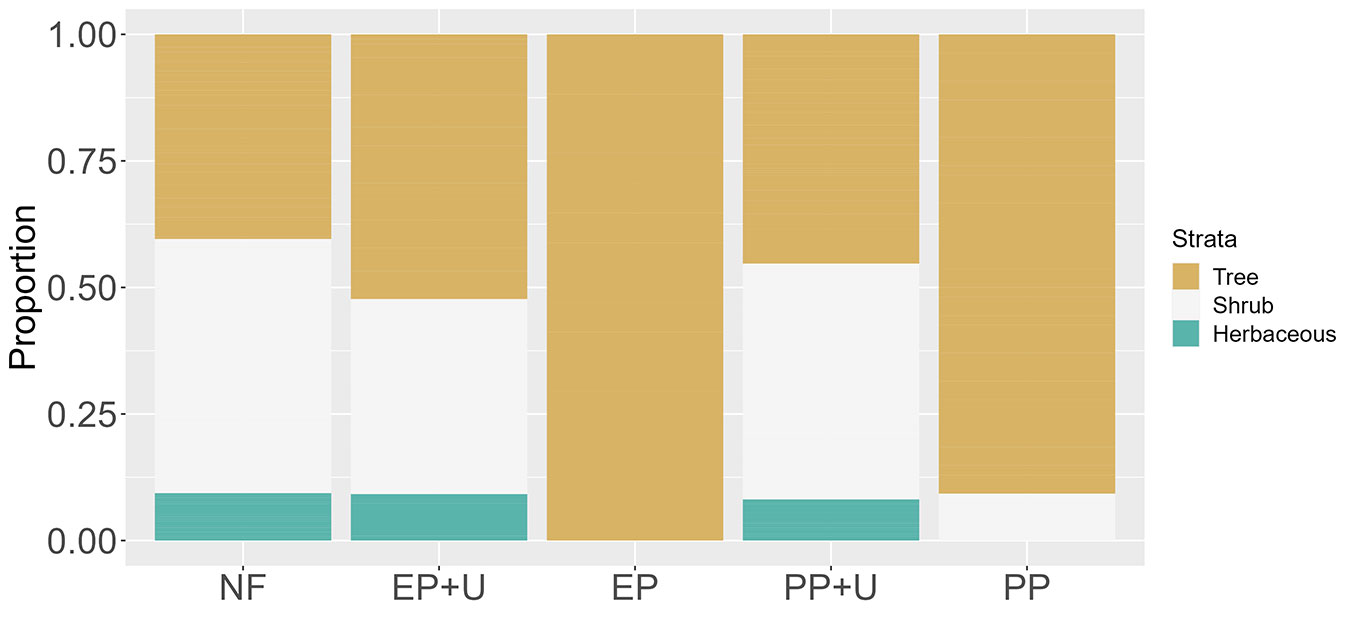

PERMANOVA analysis revealed differences between the native forest and the different management practices in strata use (R2 = 0.35, p<0.01), trophic guild composition (R2 = 0.29, p<0.01), and frequency of behaviors (R2 = 0.35, p<0.01). Among plantations, only PP+U did not differ from native forests in strata use (p=0.7 - Tab. 3). All other comparisons between pairs of habitats were statistically significant (Tab. 3). Birds used all three available strata in native forests and plantations with developed understory. In native forests, birds most frequently used the shrub stratum and the herbaceous stratum least frequently (Fig. 2). The same pattern was seen in PP+U, where the shrub stratum was slightly more used than the tree stratum. In EP+U, the arboreal stratum was the most used, followed by the shrub, and then the herbaceous stratum. In contrast, plantations without understory showed restricted stratum use. In EP, all bird records were in the arboreal stratum, whereas in PP, the arboreal stratum was predominantly used, with only a few records in the shrub stratum (Fig. 2).

Tab. 3 - Pairwise PERMANOVA results, showing comparisons between native forest and land uses for habitat strata use, trophic guilds and behaviors. P-values were adjusted using the false discovery rate method. Abbreviations are detailed in Tab. 1.

| Pairwise Permanova |

Strata | Trophic guilds | Behaviors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | R2 | Adj-p | F | R2 | Adj-p | F | R2 | Adj-p | |

| NF vs. EP+U | 7.22 | 0.12 | 0.012 | 8.08 | 0.13 | 0.003 | 4.29 | 0.07 | 0.021 |

| NF vs. EP | 26.24 | 0.34 | 0.010 | 34.68 | 0.40 | 0.002 | 29.70 | 0.37 | 0.003 |

| NF vs. PP+U | 0.41 | 0.01 | 0.696 | 6.71 | 0.10 | 0.003 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 0.437 |

| NF vs. PP | 29.93 | 0.33 | 0.010 | 40.09 | 0.40 | 0.002 | 29.82 | 0.34 | 0.003 |

| EP+U vs. EP | 7.60 | 0.14 | 0.012 | 9.49 | 0.17 | 0.002 | 8.14 | 0.14 | 0.005 |

| EP+U vs. PP+U | 5.34 | 0.09 | 0.012 | 3.09 | 0.05 | 0.020 | 2.81 | 0.05 | 0.081 |

| EP+U vs. PP | 6.10 | 0.10 | 0.012 | 9.94 | 0.15 | 0.002 | 7.09 | 0.11 | 0.004 |

| EP vs. PP+U | 22.47 | 0.30 | 0.010 | 20.03 | 0.27 | 0.002 | 19.13 | 0.27 | 0.003 |

| EP vs. PP | 3.86 | 0.07 | 0.044 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.477 | 2.44 | 0.04 | 0.081 |

| PP+U vs. PP | 24.10 | 0.29 | 0.010 | 20.84 | 0.25 | 0.002 | 18.85 | 0.24 | 0.003 |

Fig. 2 - Proportion of bird use across different strata in the five habitat units in northeastern Argentina. (NF): native forest: (EP+U): eucalyptus plantation with developed understory; (EP): eucalyptus plantation without developed understory; (PP+U); pine plantation with developed understory; (PP): pine plantation without developed understory.

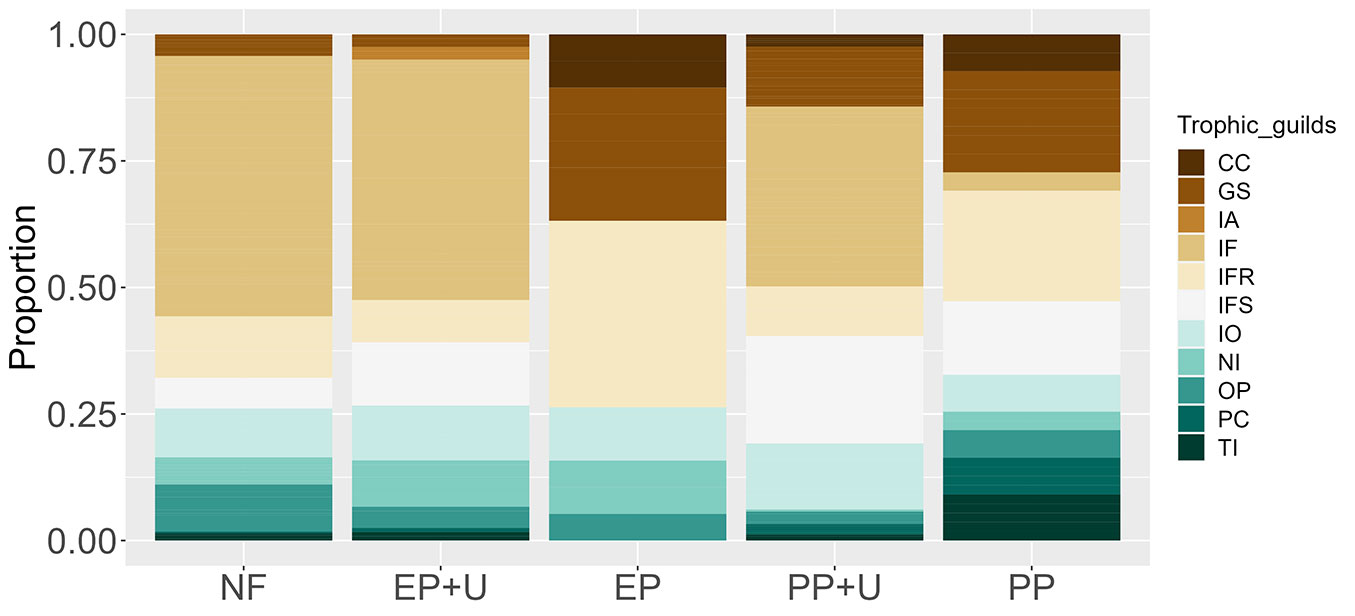

In terms of trophic guild composition, native forest differed from all types of management practices (Tab. 3). Plantations without developed understory, EP, and PP, were similar (Tab. 3), whereas all other pairwise comparisons were statistically different. The highest number of trophic guilds was recorded in EP+U, PP+U, and PP (n=10 each), followed by native forests (n=9). The fewest trophic guilds were found in EP (n=6). Insectivorous trophic guilds were the most represented across all habitats. The IF group was the most abundant in the native forest, EP+U, and PP+U, followed by IFR, IO, and IFS, respectively. In plantations without a developed understory, IFR and GS were the most abundant (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 - Proportional representation of trophic guilds across the five habitat units. Habitat abbreviations are detailed in Fig. 2.

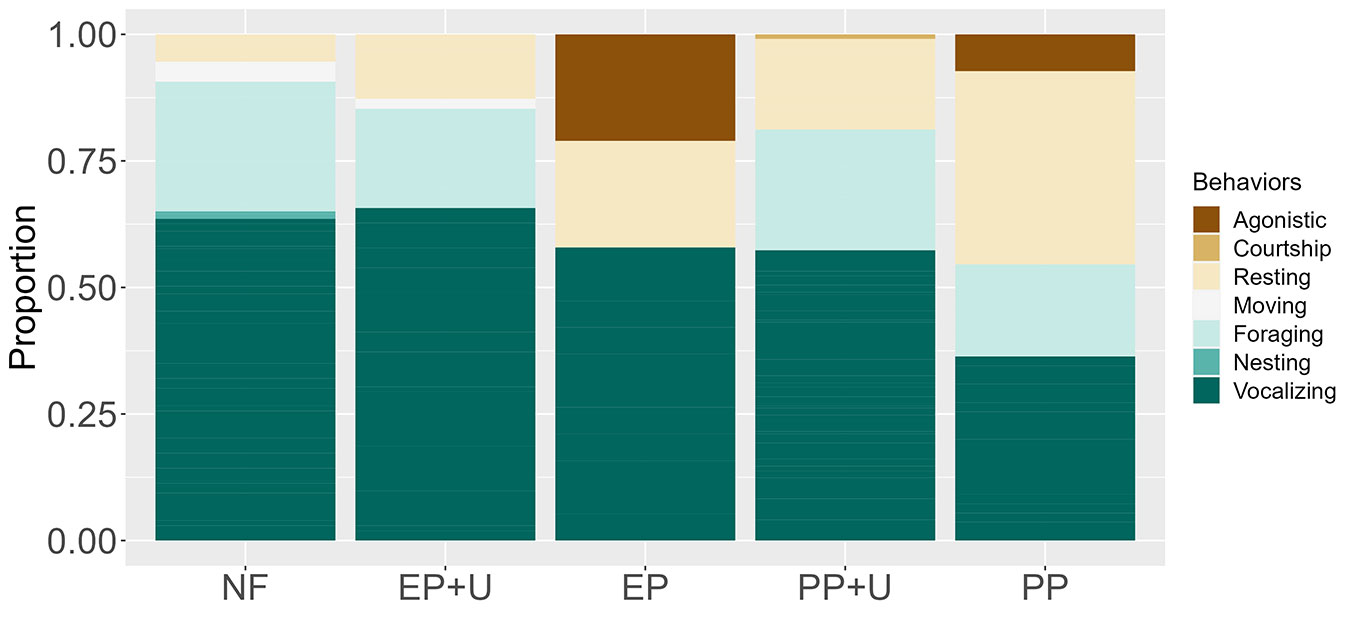

Regarding behavior categories, PP+U was the most similar to native forests. Plantations without developed understory, EP and PP, showed similar behavior profiles, as did plantations with developed understory, EP+U and PP+U (Tab. 3). The native forest had the highest number of behavior categories (n=5), while EP had the fewest (n=3). Vocalization was the most frequent behavior in all habitats except in PP, where resting was most common, followed by vocalization (Fig. 4). Foraging was the second most frequent behavior in the native forest, EP+U, and PP+U, whereas in EP, resting was the second most common behavior (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 - Proportional representation of behavior categories across the five habitat units. Habitat abbreviations are detailed in Fig. 2.

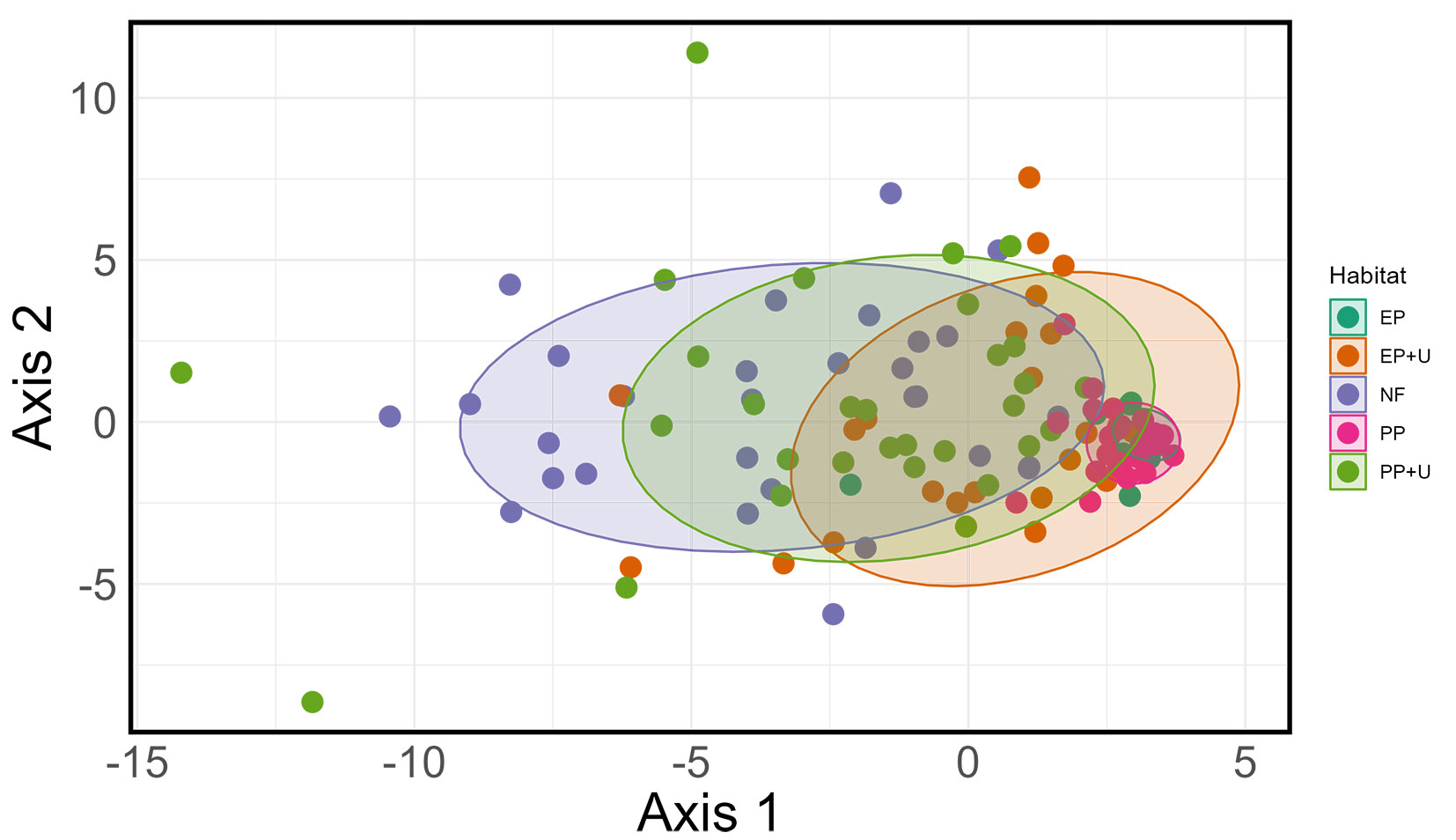

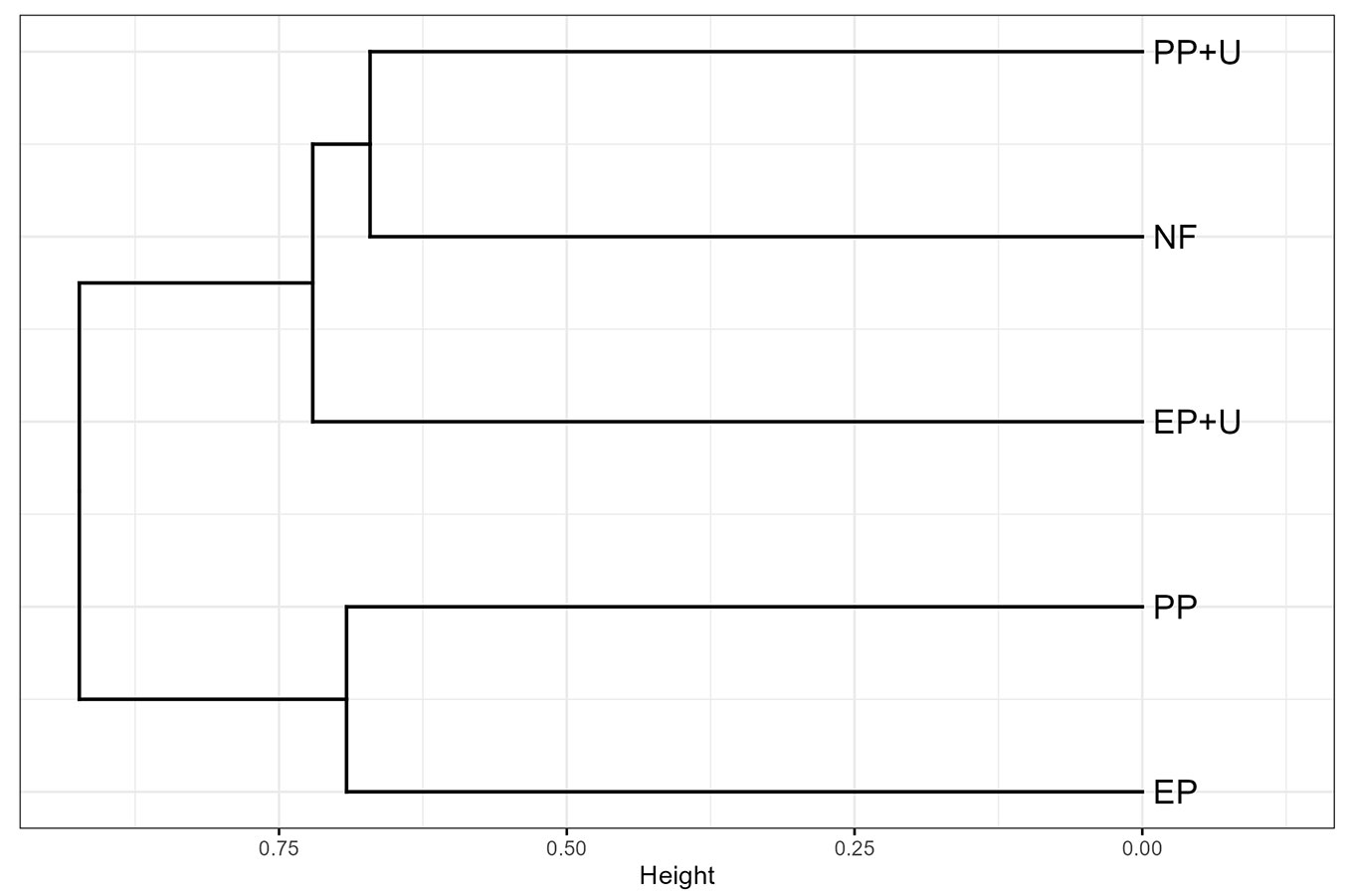

The NMDS analysis showed that Axis 1 primarily separated native forests from plantations without developed understory, underscoring the ecological differentiation driven by habitat complexity, and Axis 2 further highlighted the influence of understory vegetation in plantations shifting the functional profile of bird communities closer to that of native forests (Fig. 5). The cluster analysis corroborated the findings of the PERMANOVA analysis, indicating differences among plantation management practices. Plantations without a developed understory were clustered together. Plantations with developed understory were grouped more closely with the native forest, with PP+U showing the greatest similarity (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5 - Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot illustrating bird habitat use across five habitat units, based on vegetation strata use, trophic guild composition, and behavior categories. Confidence ellipses at the 80% level were applied to habitat units to minimize the influence of outliers and enhance visual clarity. Habitat abbreviations are provided in Fig. 2.

Fig. 6 - Cluster analysis dendrogram using the Average Linkage method and Euclidean distances, illustrating similarities in bird habitat use across different habitat units. The analysis incorporates vegetation strata use, trophic guild composition, and behavior categories. Habitat abbreviations are described in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Our study revealed that habitat use by birds varies across management practices in strata use, behaviors, and trophic guild composition. Plantations with developed understory showed habitat use patterns similar to native forests, whereas plantations without understory development supported fewer functional traits, suggesting that they act as homogenizing agents for bird communities by reducing ecological diversity and complexity. This is relevant because plantations that support a broad range of trophic guilds and diverse habitat use can provide ecosystem services beyond timber production. These services include pest control, seed dispersal, pollination, and scavenging, benefiting both biodiversity conservation and forest productivity ([30], [33]).

Birds in both native forests and plantations with a developed understory used all available strata and were abundant in the shrub stratum, including insectivorous and insectivorous-frugivorous birds. Regarding trophic requirements for insectivorous species, multi-layered forest stands with increased habitat heterogeneity support higher insect abundances ([27]); ground foragers and foliage gleaners were positively correlated with vegetation heterogeneity ([21]). The majority of understory species found in the plantations were zoochorous. This suggests that when plantation management allows the establishment of native species, the perches offered by shrubs and small trees attract birds, increasing seed rain and promoting positive feedback in the development and maintenance of the understory ([20]).

Changes in the stratification of plantation complexity were linked to changes in feeding guilds. Plantations lacking a developed understory supported fewer trophic guilds and lower overall abundance, particularly in the eucalyptus plantations. Among the most affected guilds were insectivores, particularly those that forage among vegetation, in concordance with findings elsewhere ([23]). Frugivores were the second most frequently observed guild in plantations with a well-developed understory. The ability of plantations to support frugivorous species is particularly important, as these birds contribute significantly to ecosystem functioning by promoting seed dispersal and plant diversity. Functionally diverse frugivore assemblages can generate a richer, more heterogeneous seed rain because different species feed on distinct sets of plants ([35]). This diversity in dispersal services plays a key role in ecosystem recovery, particularly in fragmented or human-modified landscapes ([18]).

Birds did not use the herbaceous stratum, probably because ground foragers need a heterogeneous ground layer for foraging ([21]). Tree density affects canopy conditions, particularly light penetration, which in turn affects the ground and lower vegetation layers and modifies the litter. The accumulation of slow-decomposing, nutrient-poor litter from pine and eucalyptus creates dense layers that acidify the soil, affect soil biota, and negatively inhibit the recruitment of native species through allelochemicals produced by eucalyptus ([37], [45]), thus limiting resources for ground-foraging birds.

We observed differences in understory plant species composition between plantations, with some species uniquely associated with each habitat type. These differences, along with differences in bark structure between pine and eucalyptus, could influence the composition of birds’ functional groups across plantation types, likely due to variations in flower production and insect abundance, as reported in other comparative studies ([12], [32]). Although we found that eucalyptus plantations differed more functionally from native forests than pine plantations, the variation within eucalyptus plantations due to management practice was particularly notable. In this context, an alternative approach to enhance biodiversity could be the implementation of mixed-species plantation management ([43]), especially in eucalyptus plantations, where ecological impacts are more pronounced.

Birds in plantations with a well-developed understory exhibited behavior patterns similar to those observed in native forests, including frequent foraging and vocalization, further indicating that they can play the same role in exotic environments, for example, as seed dispersers ([16]). However, functional similarity does not imply full ecological equivalence, as species responses vary according to habitat requirements. For example, the Dusky-legged Guan (Penelope obscura), a forest specialist and a key disperser of large seeds that smaller birds cannot handle, was detected exclusively in native forests. This suggests that plantations may be suitable for frugivores that disperse small seeds, while the dispersal of large seeds may be limited by the absence of large bird species ([46], [8]). Therefore, although properly managed plantations may resemble certain characteristics of native forests, they cannot fully replicate their ecological functions.

Conclusions

Our findings support the hypothesis that targeted management practices can increase the diversity of trophic guilds and bird use by resembling natural forests. Practices such as thinning, stand aging, mixed-species plantations, and proximity to remnants of native forests can increase understory plant diversity and enhance vegetation structural complexity, promoting functional similarity to native forests. While plantations with understory do not fully replace the functions of native forests, habitat simplification impacts can be mitigated by supporting similar, though less abundant, trophic guilds with comparable strata use and behaviors. In addition, structurally complex anthropic environments can provide functional connectivity between native forest remnants, benefiting species that require large forest areas. Our results suggest that local-scale heterogeneity created by understory vegetation significantly improves bird habitat use in plantations and highlight the importance of structural complexity in supporting not only taxonomic diversity but also functional processes essential to forest regeneration in heterogeneous landscape mosaics. Since bird responses varied among plantation types, future studies comparing understory plant species composition will help to confirm resource-based predictions. Given the increasing demand for exotic species plantations driven by the timber industry, adopting effective management of these environmental units should be a key strategy for promoting sustainable development in the region.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Establecimiento Las Marías for allowing us to conduct fieldwork on their properties and for providing logistical support. We are grateful Jorge Anselmo, Néstor Galvalisi, Marcelo Rolón Gabriela Villordo, Alejandro Azcarate, and José Anchetti for their assistance.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Centro de Ecología Aplicada del Litoral - CONICET-UNNE, Ruta 5, km 2.5, 3400 Corrientes (Argentina)

Mariano Ordano 0000-0003-0962-973x

Instituto de Ecología Regional, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán - CONICET, 4107 Yerba Buena, Tucumán (Argentina)

Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales y Agrimensura, Universidad Nacional del Nordeste, Av. Libertad 5470, 3400 Corrientes (Argentina)

Fundación Miguel Lillo, Miguel Lillo 251, 4000 San Miguel de Tucumán, Tucumán (Argentina)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Fernández JM, Thomann ML, Chatellenaz M, Ordano M (2026). Impact of management practices on habitat use by birds in exotic tree plantations in northeastern Argentina. iForest 19: 38-44. - doi: 10.3832/ifor4742-018

Academic Editor

Mirko Di Febbraro

Paper history

Received: Oct 09, 2024

Accepted: Jul 15, 2025

First online: Feb 06, 2026

Publication Date: Feb 28, 2026

Publication Time: 6.87 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2026

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 7

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 1

Abstract Page Views: 2

PDF Downloads: 4

Citation/Reference Downloads: 0

XML Downloads: 0

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 1

Overall contacts: 7

Avg. contacts per week: 49.00

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

(No citations were found up to date. Please come back later)

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Effect of the plantation age on the use of Eucalyptus stands by medium to large-sized wild mammals in south-eastern Brazil

vol. 8, pp. 108-113 (online: 21 July 2014)

Research Articles

Diversity and distribution patterns of medium to large mammals in a silvicultural landscape in south-eastern Brazil

vol. 11, pp. 802-808 (online: 14 December 2018)

Research Articles

Bird response to forest structure and composition and implications for sustainable mountain forest management

vol. 19, pp. 18-27 (online: 11 January 2026)

Research Articles

Indicators for the assessment and certification of cork oak management sustainability in Italy

vol. 11, pp. 668-674 (online: 04 October 2018)

Research Articles

Understory vegetation dynamics and tree regeneration as affected by deer herbivory in temperate hardwood forests

vol. 10, pp. 837-844 (online: 26 October 2017)

Research Articles

Effects of low-impact logging on understory birds in the Brazilian Amazon

vol. 14, pp. 122-126 (online: 08 March 2021)

Research Articles

Effects of forest management on bird assemblages in the Bialowieza Forest, Poland

vol. 8, pp. 377-385 (online: 02 October 2014)

Research Articles

Variability of ant community composition in cork oak woodlands across the Mediterranean region: implications for forest management

vol. 10, pp. 707-714 (online: 27 July 2017)

Research Articles

Could cattle ranching and soybean cultivation be sustainable? A systematic review and a meta-analysis for the Amazon

vol. 14, pp. 285-298 (online: 08 June 2021)

Research Articles

Forest and tourism: economic evaluation and management features under sustainable multifunctionality

vol. 2, pp. 192-197 (online: 15 October 2009)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword