Early flowering and genetic containment studies in transgenic poplar

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 5, Issue 3, Pages 138-146 (2012)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor0621-005

Published: Jun 13, 2012 - Copyright © 2012 SISEF

Research Articles

Collection/Special Issue: COST Action FP0905

Biosafety of forest transgenic trees and EU policy directives

Guest Editors: Cristina Vettori, Matthias Fladung

Abstract

Despite of the immense potential of gene technologies for tree breeding, release of genetic modified trees is still very rare. Biosafety concerns have hitherto limited application of gene technologies. The potential risks of transgenic trees, in particular transfer of recombinant DNA into the gene pool of a given species via vertical gene transfer, have been motive of concern. Biosafety research may allow avoiding potential risks of this technology. However, the evaluation of strategies for prevention of vertical gene transfer, probably the most important concern toward transgenic trees, has been hindered by the long time they require to reach the reproductive phase. We tested different strategies for promoting early flowering in poplar, aiming the development of a system for biosafety studies on gene containment. Early flowering poplar containing the 35S::LFY or HSP::FT gene constructs allowed first approaches for the faster evaluation of gene containment. However, some drawbacks, e.g., disturbed vegetative growth and flower development, still limit their potential application on biosafety research. A non-transgenic hybrid aspen showing a short vegetative phase was successfully used for the evaluation of the PrMALE1::STS sterility gene construct.

Keywords

Introduction

The promising prospects offered by gene technologies, especially for tree breeding, have promoted their use in the forestry. An increasing demand of renewable resources has been predicted to meet the energy needs of a growing world population. In the range of different options of renewable resources, woody biomass plays an important role mainly originating from forests including primary or wild forests. Forest plantations with improved genotypes might represent a solution for the increasing pressure on wild forest ecosystems. However, ecological boundaries between wild forests and plantations can represent a threat to their integrity.

Gene flow from non-native forest trees and taxa resulting from traditional breeding has been motive of concerns in the past ([18]). These concerns have increased since private companies and research institutes worldwide show interest on incorporating genetic engineering into forest tree breeding programs. Release of transgenic trees harbouring particular genes into forest ecosystems would in fact represent an additional risk factor to natural ecosystems.

Until now, strategies for gene flow avoidance between non-native trees taxa derived from traditional breeding have been limited to geographic separation of sexual compatible species. The development of “gene containment” methods using genetic engineering is a promising solution for a more efficiently avoidance of undesired gene flow, not only from genetic modified trees (GM). The incorporation of sterility genes into transgenic lines of trees was proposed to reduce or even avoid gene flow of transgenes into non-transgenic relatives ([47]). An additional advantage of sterile trees would be the reduction of energetic costs necessary for development of reproductive structures ([4], [35]).

Various sterility gene constructs have been tested with different levels of success in crop plants, e.g., by expression of deleterious genes in flower organs, like barnase ([38], [31], [17]), orfH522 ([37]), monooxygenase (MNX - [16]), stilbene synthase (STS - [9], [22]), the gene for ribosome inactivating protein ([39]) and RNA interference ([36]). Specific floral regulatory promoters to direct expression of genes in reproductive structures have been found in crop plants, e.g., TA29 promoter from Nicotiana tabacum ([25], [31]) and forest tree species, e.g., PrMALE1 from Pinus radiata ([21]) and PTD from poplar ([46]).

The number of publications on sterility induction in forest trees is still very low ([33], [46], [11], [27], [20], [51]). Most sterility approaches reported until now were based on gene constructs used successfully in crop plants. Heterologous floral specific promoters can direct activity of cytotoxic gene expression in non-target, vegetative tissues (“leaky” expression) generating in some cases a lower performance of transgenic plants ([27], [33], [46]). Use of floral specific promoters from forest trees have been proposed to overcome such handicaps ([46]).

The main factor hindering biosafety research on forest trees is the prolonged vegetative phase. This phase is quite variable lasting in some tree species until 40 years (e.g., Fagus sylvatica L. - [32]). Therefore early flowering trees, either natural or transgenic ones, are very important tools for biosafety research. Most genes involved in the regulation of flowering have been discovered in Arabidopsis (reviewed in [29]). However, flowering time genes have also been studied in woody plants like birch ([6], [7]), poplar ([42], [3], [23]) and apple ([50]).

Several heterologous approaches with flowering time genes have allowed induction of early flowering in perennials. The overexpression of BpMADS4 induce early flowering in birch (Betula pendula - [7]) and apple (Malus × domestica Borkh. - [13]), but not in poplar ([19]). BpMADS4 transgenic lines are currently being used for apple breeding ([14]). The apple gene MdFT2, homologous of FT gene, promoted early flowering in apple and poplar ([48]). Arabidopsis flowering time genes Leafy ([45]) and Flowering locus T ([2]) allow the hitherto most efficient early flowering induction in poplar ([52], [42], [54]). Furthermore, it has been shown that transgenes can induce early flowering in trees more efficiently than cisgenes ([42], [54], [14], [48]). Possibly, transgenes are less prone to “endogenous repressors” than cisgenes ([42]).

In this study, we evaluated different early flowering systems in poplar aiming their use on biosafety studies on gene containment. We confirmed induction of sterility with the gene construct PrMALE1::STS in the non-transgenic hybrid aspen clone T89.

Material and methods

Plant material, culture and genetic transformation

In vitro cultures of male hybrid aspen (Populus tremula L. x P. tremuloides Michx., clone T89) and Populus tremula L., clone W52 were used for generation of transgenic lines. Plants were grown on solid McCown Woody Plant Medium (WPM, Duchefa M0220 - [30]) containing 2% Sacharose, 0.6% Agar (Agar Agar, Serva, 11396). Genetic transformations were carried out employing the Agrobacterium-mediated approach ([12]) using the Agrobacterium strain EHA105. WPM medium for the regeneration of transgenic plants was supplemented with 0.01% Pluronics F-68 (Sigma P-7061), thidiazuron (0.01 μM) and antibiotics, cefotaxime (500 mg L-1) for Agrobacteria elimination, and kanamycin (50 mg L-1) or hygromycin (20 mg L-1) for selection of transgenic shoots. Early flowering sterile plants (see below) were transferred to growth chambers (Weiss Technik) under the following culture conditions: light period: 16/8 (day/night), light intensity: 300 µE m-2 sec-1, lamps: Phillips TLM 140W/33RS, relative humidity: 70%, temperature: 22/19 °C. After a culture period of 6-18 months in the growth chambers transgenic plants were transferred to, and further grown in, a standard S1 greenhouse under natural daylight conditions.

Induction of early flowering with genetic transformation

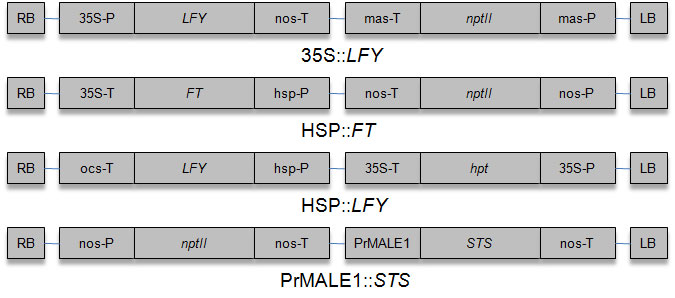

Performance of early flowering poplar systems based on gene constructs (Fig. 1) 35S::LFY ([52]), 35S::FT ([3]), HSP::LFY (see below) and HSP::FT ([54]) was evaluated. Both the FT and LFY constructs containing Arabidopsis genes were kindly provided by O. Nilsson (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Umeå, Sweden). HSP promoter is derived from the soybean heat-inducible promoter Hsp6871 ([44]). The HSP::LFY vector was constructed by DNA Cloning Service (Hamburg, Germany).

Cloning of gene constructs: (a) HSP::FT: HSP promoter was ligated to FT cDNA, and was contained in the Gateway binary vector pK2GW7 ([24]); (b) HSP:: LFY: LFY cDNA was ligated to binary vector p6-HSP-TP-OCS (DNA Cloning Service, Hamburg, Germany) after digestion with Bgl II and Xho I. Activation of flowering time genes was carried out in growth chambers with a heat treatment (1h, 40 °C, 4-6 weeks).

Induction of sterility using genetic transformation

Poplar was transformed with the PrMALE1 ::STS gene construct ([21]), kindly provided by C. Walter (Forest Research Institute, Rotorua, New Zealand). Generation of transgenic lines containing PrMALE1::STS and one early flowering gene construct (HSP::FT or 35S::FT) was carried out using simultaneously two Agrobacterium strains, one containing the gene construct PrMALE1::STS and the other one HSP::FT or 35S::FT. Transgenic lines containing both gene constructs were selected using molecular analysis.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription

Tissues (leaves, stems and roots) were collected and frozen in liquid N2 and stored at -80 °C until RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated using the Plant RNA Isolation Mini Kit (Agilent, Wilmington, USA). Around 60 mg of liquid nitrogen frozen tissues were ground in Eppendorf tubes using metal balls and a Retsch mill (Retsch MM2, Germany). RNA was quantified using spectrophotometric OD260 measurements with a Nanodrop 1000 (Thermoscientific, Wilmington, USA) and RNA quality was assessed by OD260/ OD280 and OD260/OD230 ratios (both ratios were maintained between 1.8 and 2.1) and using the Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc. Palo Alto, CA - RIN values > 6). Contaminating DNA was removed from RNA samples using the Ambion turbo DNA-free (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized with 30 ng µl-1 RNA using the DyNAmo cDNA Synthesis Kit (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) with Oligo (dT)15 primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Expression of STS gene in transgenic plants

Expression of STS was studied using RT- PCR. Gene UBQII was used as a reference gene. Primers (Tab. 1) were designed using Primer3Plus software ([43]) with melting temperatures around 60 °C. PCR reactions were done in a 20 μl volume containing 300 nM of each primer, 2 μl of cDNA sample (~3.5 ng of input RNA) and Maxima Hot Start Taq DNA Polymerase (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany). RT- PCR was performed using the following parameters: 10 min. at 95 °C and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 sec, 60 °C for 1min and 72 °C for 1 min.

Tab. 1 - Sequence of primers used in this study (5’- 3’).

| Primer | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| PrMALE1 | GGT GCC CAA AGC ATT GTA GCA | CCA CGA CGT TCC CGT TTG AT |

| STS | AAA CGC TCA ACG TGC CAA GG | AGT TTC CGG CAA TGG CTC CT |

| LFY | GTT GGT GAA CGG TAC GGT AT | ACT AGA AAC GCA AGT CGT CG |

| FT | GTT GGA GAC GTT CTT GAT CCG | TCT TCT TCC TCC GCA GCC ACT |

| UBQII | ACA CCA TCG ACA ACG TCA AA | GTG AGC GCA ATT CAG AGA CA |

Extraction of DNA and molecular analysis

DNA extraction was followed by a standard protocol adapted from Doyle & Doyle ([5]), using 0.5-1.0 g leaf material and a modified extraction buffer [2% alkyltrimethylammonium bromide (ATMAB), 0.1 M Tris-HCl, 0.02 M disodium-EDTA (pH 8.0), 1.4 M NaCl, 1% PVP]. Standard PCR techniques were used to detect and amplify transgenes. The PCR reaction used for all primers (Tab. 1) consisted of 94 °C / 2 min, followed by 40 cycles (94 °C / 1 min, Ta / 2 min, 72 °C / 2 min) and finally 72 °C / 5 min. Southern hybridisations were carried out with 20 μg genomic DNA. DNA was digested enzymatically and separated using a 1.5% agarose gel and transferred onto a membrane by capillary transfer (Nylon membrane positively charged, Roche) in alkaline conditions. Prehybridization and hybridization were performed with the non-radiactive DIG (digoxigenine) system using DIG- dUTP-labelled gene probes ([10]). DIG probes were prepared with a PCR amplification Kit (PCR DIG Probe Synthesis Kit, Roche) using the different plasmids with the respective primer pairs. Probe hybridization and chemiluminescent reaction were performed according to Roche instructions with some modifications ([10]).

Microscopic observation of anthers derived from transgenic plants

Anthers obtained form early flowering and early flowering-sterile plants were observed under an optical microscope to confirm presence or absence of pollen grains. Pollen germination tests were carried out with fresh pollen using culture medium (Saccharose 10%, Phytagel 7.5 g L-1). FDA test: microspore viability was estimated staining with fluorescein diacetate ([53]).

Results

Induction of early flowering in poplar with genetic transformation

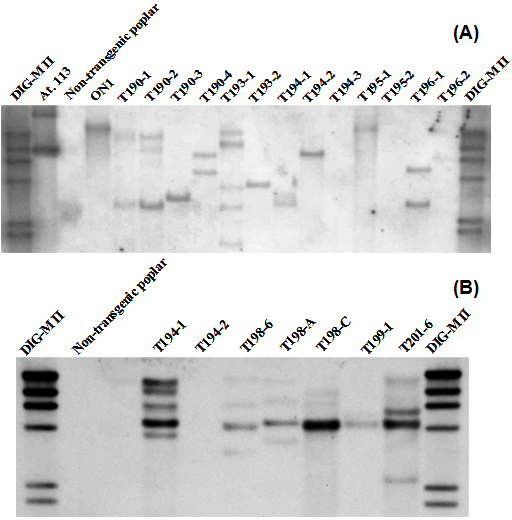

Genetic transformation was performed with different gene constructs containing the 35S or HSP promoter and the flowering time genes LFY or FT. We obtained five to ten transgenic lines with each gene construct. Transgenic lines obtained were analyzed with PCR and Southern-Blot analysis (Fig. 2). Single copy transgenic lines were selected for further studies.

Fig. 2 - (A): Southern-blot analysis of DNA extracted from HSP::FT aspen leaves. Genomic DNA restriction with Sac I. Twenty µg of genomic DNA from leaves were enzymatically digested, electrophorized in an agarose gel, blotted and subsequently detected using a digoxigenine-labelled FT probe; (B): Southern-blot analysis of DNA extracted from PrMALE1::STS aspen leaves. Genomic DNA restriction with Hind III. Twenty µg of genomic DNA from leaves were enzymatically digested, electrophorated in an agarose gel, blotted and subsequently detected using a digoxigenine-labelled STS probe.

35S::LFY: early flowering lines where obtained with both poplar clones (T89 and W52). This early flowering model ([52]) was used for biosafety research before ([46], [20]).

Incidence of sterility and disturbed plant growth reduces the utility of this model for biosafety research ([20]). Early flowering occurs in spring and during the summer time. However, pollen grains were obtained only from greenhouse plants in spring. Furthermore, the presence of pollen in flowers was very variable, fluctuating yearly between 0% (only sterile flowers) to 100%. Out of these results, we concluded that LFY effectively promotes flowering but not microsporogenesis.

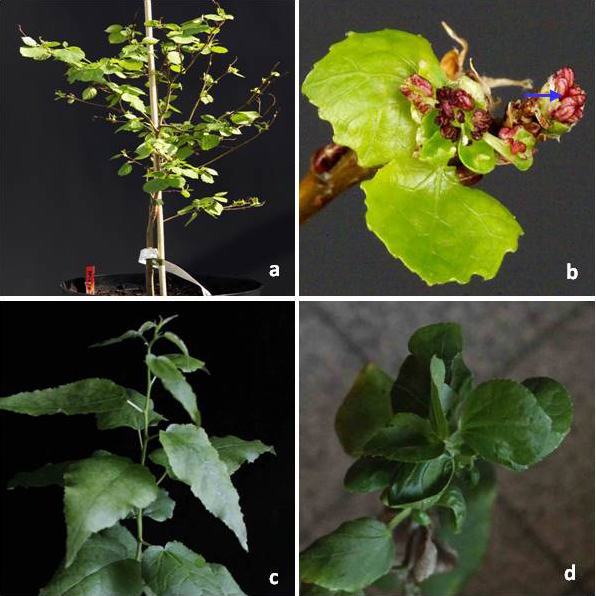

HSP::LFY: The rationale behind promoter replacement, HSP instead of 35S promoter, was the avoidance of dwarf plant growth caused by constitutive LFY expression. This approach allowed to obtain transgenic plants with a normal vegetative growth. However, heat-treatment disturbed plant growth (indicating LFY expression), and no flowering could be obtained (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 - Flowering induction in poplar using genetic transformation with LFY gene. Arrow shows single flower. 35S::LFY: dwarf vegetative growth (a), single flowers (b); HSP::LFY: normal vegetative growth (c), disturbed growth after heat treatment (1h, 40°C, 4-6 weeks). No flowers were obtained.

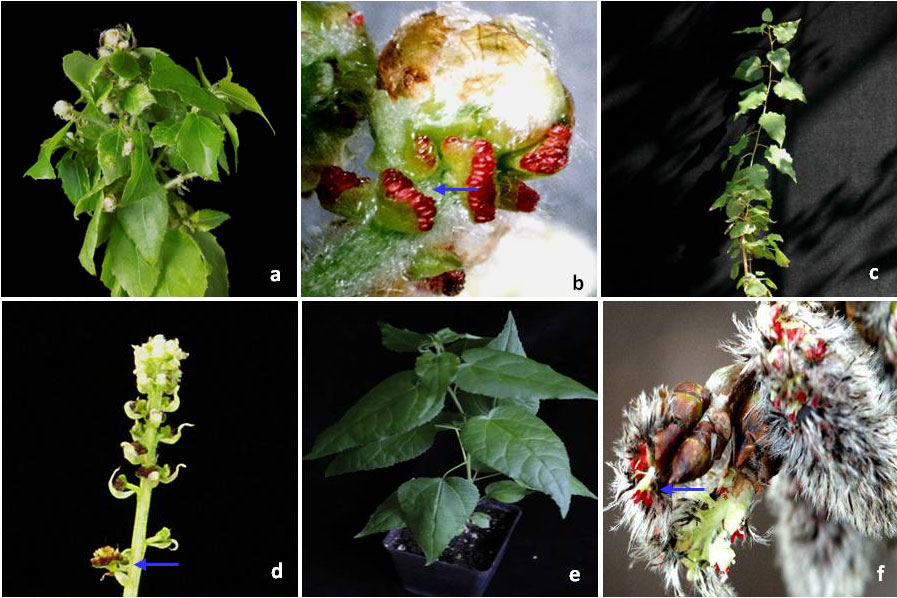

35S::FT: Only one transgenic line out of seven obtained in total showed early flowering under in vitro and growth chamber conditions. The flowers obtained under growth chamber conditions resembled strongly naturally developed poplar catkins (Fig. 4). However, early flowering was not stable and after one to two years no more flowers developed.

Fig. 4 - Flowering induction in poplar using genetic transformation with flowering time genes. Arrows show single flowers. 35S::FT: quite normal vegetative growth (a), catkin (b); HSP::FT: normal vegetative growth (c), catkin (d); non-transgenic T89 plants: vegetative growth (e), catkins (f).

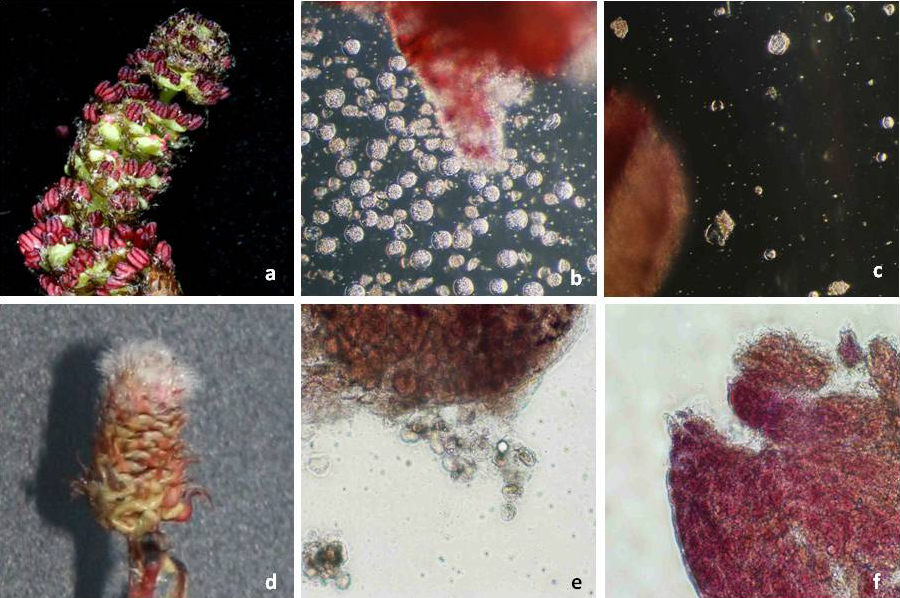

HSP::FT: The expression of the FT gene regulated by the heat-inducible promoter allowed effective flowering induction and a normal looking plant phenotype. Early flowering lines where obtained with both poplar clones (T89 and W52). HSP::FT flowers are grouped in catkins resembling those from naturally grown poplar. However, there are still differences between naturally developed (wild) and HSP::FT poplar flowers (Fig. 4): no normal flower buds developed, catkin bracts were absent and microsporogenesis was not induced. Some few flowers, derived from summer heat-treated plants (Tab. 2), showed pollen grains the next spring (Fig. 5c-d). However, flowers obtained in the summer after the heat treatment lacked always pollen grains.

Tab. 2 - Genetic transformation of poplar with flowering time genes. (*1): flowers with/lacking pollen grains can be found; (*2): normal vegetative growth until heat treatment; (*3): flowers contain seldom pollen grains.

| Gene construct | Poplar clone | Flowering | Vegetative growth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro (Pollen) | Greenhouse (Pollen) | |||

| 35S::LFY | T89 | + (-) | + (+*1) | dwarf |

| W52 | + (-) | + (+*1) | dwarf | |

| HSP::LFY | T89 | - | - | normal *2 |

| W52 | - | - | normal *2 | |

| 35S::FT | T89 | + (-) | - | normal |

| W52 | - | - | normal | |

| HSP::FT | T89 | + (-) | + (*3) | normal |

| W52 | + (-) | + (*3) | normal | |

Fig. 5 - Catkin and anthers from early flowering heat-inducible poplar (a, b, c) and transgenic line T194-1 (d, e, f) transformed with the sterility construct PrMALE1::STS. HSP::FT: (a) catkin of HSP::FT plant; (b) anthers containing abundant pollen grains (seldom occurring event); (c): anthers containing low number of disturbed pollen grains. HSP::FT + PrMALE1::STS (Line T194-1): (d) abnormal catkin from early flowering transgenic line transformed with sterility gene construct PrMALE1::STS; (e): anther with sterile pollen grains; (f): anther devoid of pollen grains.

Evaluation of gene containment strategies in poplar

Transgenic lines were analyzed with PCR and Southern blot experiments (Fig. 2). Genetic transformation approach using the poplar wildtype strain W52 and combining two Agrobacterium strains, containing the PrMALE1::STS and one early flowering gene construct (35S::FT or HSP::FT), produced many transgenic lines containing one single gene construct but only two lines containing both gene constructs, lines T198-A and T194-1 (Fig. 2). The line T198-A (PrMALE1::STS/35S::FT) transformed with 35S::FT did not developed flowers under in vitro or greenhouse conditions. Similar results were obtained with single 35S::FT transgenic lines, as mentioned before. Transgenic line T194-1 (PrMALE1::STS/HSP:: FT) containing the HSP::FT produced catkins with disturbed development (Fig. 5). However, due to disturbed pollen development in HSP::FT poplar, no clear conclusions can be drawn regarding efficiency of the PrMALE1::STS sterility with the poplar wildtype strain W52 containing this early flowering system.

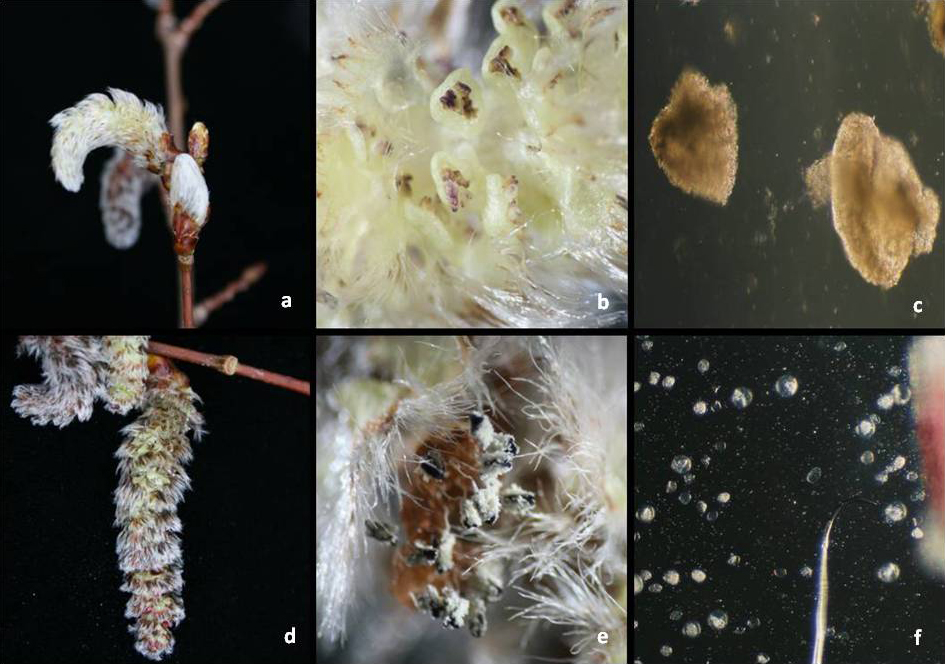

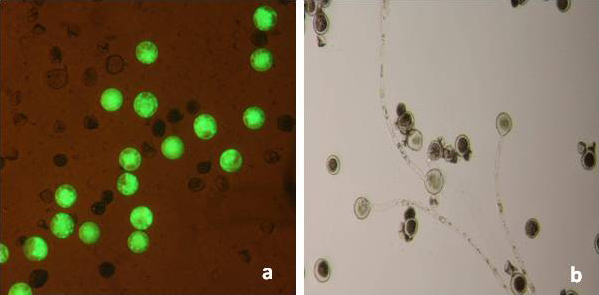

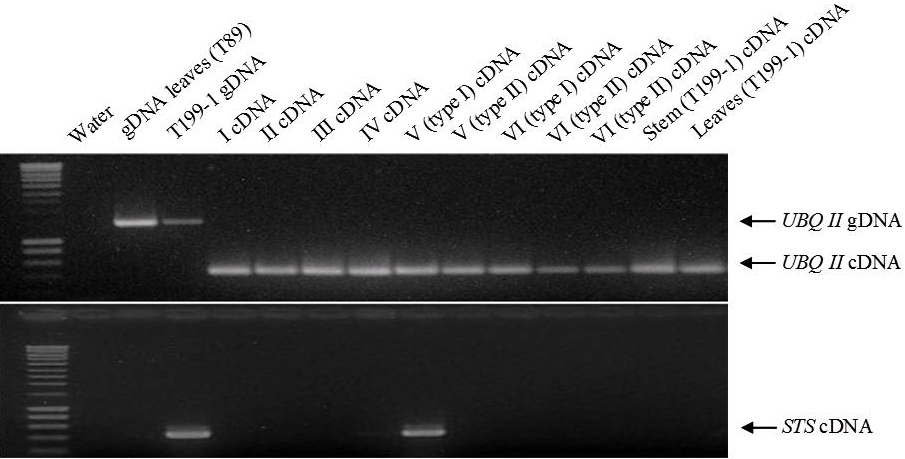

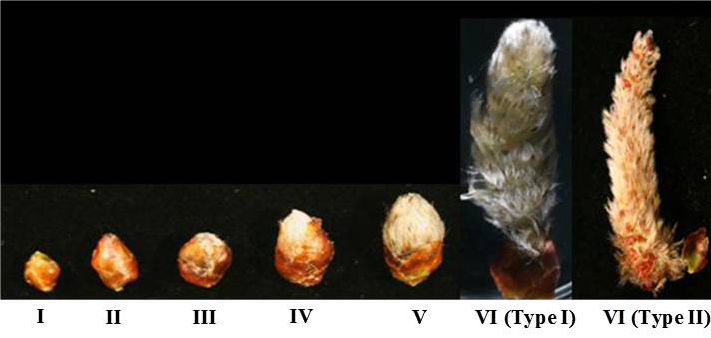

Genetic transformation of the non-transgenic hybrid aspen clone T89 allowed a more reliable evaluation of the sterility efficiency of PrMALE1::STS gene construct five years after genetic transformation. Transgenic line T199-1 contained the sterility gene construct PrMALE1::STS. Vegetative growth of PrMALE1::STS transgenic plants resembled that of non-transgenic control plants. Development was disturbed in 68% of catkins (type I catkins), and those catkins were lacking pollen grains (Fig. 6, Tab. 3). However, pollen grains were obtained from some normal-looking catkins (type II catkins). The presence of viable pollen grains in catkins type II was confirmed with FDA tests, in vitro germination and crossings (Tab. 3, Fig. 7). Expression studies of STS gene were carried out in young catkins from transgenic plants (Fig. 9). The expression of STS was confirmed only in young catkins type I and not in type II, and no leaky expression was detected in leaves, stems or roots (Fig. 9). STS expression was weak in type I catkins at phase IV and stronger during phase V (Fig. 8 and Fig. 9). No STS expression was detected in mature type I catkins.

Fig. 6 - Genetic transformation of wildtype hybrid aspen clone T89 with PrMALE1::STS. (a): catkin type I (sterile); (b): disturbed anther growth; (c): anthers without pollen grains; (d): catkin type II (non-sterile); (e): anthers with pollen grains; (f): pollen grains.

Tab. 3 - Frequency of sterility in catkins from PrMALE1::STS transgenic hybrid aspen clone T89. (*): no pollen grains.

| Catkins | Catkins with pollen |

in vitro growth |

FDA | Crossings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catkin type I | 0/15 (0 %) |

* | * | * |

| Catkin type II | 7/7 (100 %) |

+ | + | + |

| Catkins obtained in total | 22 (32%) |

+ | + | + |

Fig. 7 - Viability tests of pollen grains from (catkins type II, line T199-1): (a) FDA test; (b) pollen germination tests.

Fig. 9 - Stilbene synthese gene (STS) expression in flower buds and catkins at different developmental stages (see ) of the PrMALE1::STS transgenic line T199-1. STS activity was detected in flower buds at the stage V (type I). UBQII gene was used as a control.

Fig. 8 - Catkin development in transgenic PrMALE1::STS hybrid aspen clone T89 (Line T199-1). Flower buds (I, II, III, IV, V), sterile (VI type I) and non-sterile (VI type II) catkins.

Discussion

Early flowering in poplar

The development of more efficient early flowering poplar systems would allow faster biosafety studies on genetic containment. Therefore, we evaluated different methods to induce early flowering in poplar. After some unsuccessful approaches using growth inhibitors like Paclobutrazol and Daminozide in the past (unpublished results), we focused on genetic transformation with flowering time genes for achieving this aim. The constitutive expression of the LFY gene ([52]) allowed us initiating containment studies in poplar ([20]). However, overexpression of LFY produces many side effects on vegetative growth and flower development, which can be detrimental for their broad use in biosafety research.

We tested a new approach, with the HSP promoter, expecting an effective and less detrimental effect of LFY expression on flowering and plant growth. Our results showed that vegetative growth was significantly improved when LFY expression was under the control of the HSP promoter. However, activation of LFY through heat treatments (1h, 40°C, 4-6 weeks), disturbed vegetative growth and no flowering was obtained. It is not clear why a short LFY activation still disturbs vegetative growth strongly and do not induce flowering. Short gene activation with the HSP promoter did not lead to an improvement of the LFY early flowering poplar model.

Early flowering systems based on the FT gene from Arabidopsis, 35S::FT and HSP:: FT, were successful on flower induction. However, disturbed microsporogenesis is still a problem. The constitutive overexpression of FT promoted development of normal looking catkins during in vitro culture and growth chamber cultivation. However, no flowers were developed on 35S::FT transgenic poplar grown in the greenhouse (Tab. 2). Gene silencing of FT or some other flowering time genes may be avoiding long term flowering in 35S::FT system. The HSP::FT gene construct allowed a much more reliable flower induction compared to 35S::FT. However, pollen grains were obtained very seldom, and only during spring in summer heat-treated greenhouse plants (Tab. 2).

Several approaches have been successful of early induction of completely fertile flowers in woody plants. The constitutive expression of CiFT (the citrus FT homologue) in Trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. - [8]), LFY or AP1 in Carrizo citrange (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck × Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf. - [40]) and BpMADS4 from birch ([7]) in apple (Malus domestica Borkh. - [13]) induced early formation of fertile flowers. However, phenotype induced by introduced flowering time genes is very variable depending of the plant species. For instance, the BpMADS4 gene construct from birch was also transferred to poplar; instead of early flower formation a retarded senescence was observed in resulting transgenic lines ([19]). Thus, it is not clear why the transformation with a single gene can promote the development of flowers and pollen grains in some plant species but not in others.

Hitherto available transgenic early flowering poplar models show many drawbacks when used as standard tool in biosafety research. Disturbed microsporogenesis is still the main problem detected in those models. Research aiming improvement of early flowering may provide a more efficient tool for this aim in the next future. Use of natural early flowering clones, as it has been reported for poplar ([34]), may represent a reliable alternative for such studies. Our results showed that the hybrid aspen T89 represent an appropriate choice for such studies as flowers were obtained four to five years after genetic transformation; Populus tremula L. clones begin flowering usually after a vegetative phase of seven to ten years. However, development of faster flowering systems would facilitate application on biosafety studies. The improvement of early flowering system based on genetic transformation can be carried out with some other flowering genes (single gene approach) or following a co-transformation strategy with flowering genes (gene stacking approach).

Evaluation of gene containment strategies in poplar

Biosafety studies were initiated in our group with the first available early flowering model, 35S::LFY ([52]). In a former publication, we showed with this model that genetic transformation with CGPDHC::Vst1 promoted sterility in poplar ([20]). However, the weak performance of 35S::LFY was a strong burden for generation and maintenance of double transgenic lines with other sterility constructs, e.g., TA29::Barnase (unpublished results). Those transgenic lines showed a very weak performance, and could not be grown under greenhouse conditions. We suppose that leaky Barnase expression, due to unspecific TA29 promoter activity ([28]), has represented a strong burden for 35S:: LFY poplar.

Important progress has been reached on flowering time regulation in plants (reviewed in [49]). Consequently, we incorporated new early flowering models into our research. Two gene constructs based on the FT gene, HSP::FT and 35S::FT, were used for early flowering induction. The vegetative growth and flower development of double transgenic lines (T194-1 and T198-A) was significantly improved with both models. However, both systems do not represent a good option for biosafety studies, due to disturbed pollen development.

In the frame of our biosafety work, a field release was also planed. Therefore, transgenic lines were also generated with normal flowering poplar W52 (non-transgenic). Some genetic transformations were also carried out with hybrid aspen clone T89. Resulting transgenic lines were maintained in the greenhouse for many years. However, no field release could be carried out, due to the increasing legal restrictions toward GMOs in Germany. After four years in the greenhouse, we detected first flowers in hybrid aspen clone T89 containing the MALE1::STS sterility construct (transgenic line T199-1). This result was surprising, because other poplar clones used in our institute flower only after seven to ten years.

Hybrid aspen clone T89 allowed us a first approach for evaluation of the MALE1::STS sterility construct under controlled conditions. STS-induced male sterility using the gymnosperm promoter PrMALE1 was demonstrated in tobacco before ([21]). STS inhibits flavonol biosynthesis in the tapetum, leading to a disturbed pollen development. The number of pollen grains was reduced and a very low pollen germination was reported in 2/10 transgenic lines ([21]). In hybrid aspen, pollen development was disturbed in 68% of catkins. We confirmed specific activity of PrMALE1 in catkins (Fig. 9). However, a low activity of this promoter in some cells, due to variable gene expression level, may be a possible reason for presence of viable pollen grains in some catkins. Epigenetic modifications may result in a mosaic gene expression ([1], [41], [15]). T-DNA positional effects may be playing an important role too ([26]). These results were derived from nine ramets derived from the same transgenic lines. A higher number of transgenic lines would possible allow obtaining lines showing a more efficient sterility induction.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the German Ministry of Education and Research (Biosafety Research; project number 0315210C). We thank C. Walter (Forest Research Institute, Rotorua, New Zealand) and O. Nilsson (University Umeå, Sweden) for kindly providing gene constructs, D. Ebbinghaus and A. Schellhorn, for helpful technical assistance in the lab, and greenhouse staff (M. Hunger, G. Wiemann, R. Ebbinghaus, M. Spauszus) for plant cultivation. This work has been presented at the “First Biosafety Workshop” of COST Action FP0905 held in Hamburg (Germany) on September 9th, 2010.

Box 1 - List of Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used thoughout the paper:

- GM: genetic modified

- FT: flowering locus T

- HSP: heat shock promoter

- LFY: Leafy

- STS: Stilbene synthase

- UBQII: Ubiquitin II

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

D Lehnhardt

O Polak

M Fladung

Johann Heinrich von Thünen-Institut (vTI), Intitute of Forest Genetics, Sieker Landstr. 2, D-22927 Großhansdorf (Germany)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Hoenicka H, Lehnhardt D, Polak O, Fladung M (2012). Early flowering and genetic containment studies in transgenic poplar. iForest 5: 138-146. - doi: 10.3832/ifor0621-005

Academic Editor

Gabriele Bucci

Paper history

Received: Jan 24, 2012

Accepted: May 23, 2012

First online: Jun 13, 2012

Publication Date: Jun 29, 2012

Publication Time: 0.70 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2012

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 66121

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 53626

Abstract Page Views: 4615

PDF Downloads: 5874

Citation/Reference Downloads: 32

XML Downloads: 1974

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 5019

Overall contacts: 66121

Avg. contacts per week: 92.22

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2012): 13

Average cites per year: 0.93

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Review Papers

Fifteen years of forest tree biosafety research in Germany

vol. 5, pp. 126-130 (online: 13 June 2012)

Review Papers

Prospects for evolution in European tree breeding

vol. 17, pp. 45-58 (online: 06 March 2024)

Research Articles

Adaptive response of Pinus monticola driven by positive selection upon resistance gene analogs (RGAs) of the TIR-NBS-LRR subfamily

vol. 10, pp. 237-241 (online: 02 February 2017)

Technical Advances

Gene flow in poplar - experiments, analysis and modeling to prevent transgene outcrossing

vol. 5, pp. 147-152 (online: 13 June 2012)

Research Articles

Genetic variation and heritability estimates of Ulmus minor and Ulmus pumila hybrids for budburst, growth and tolerance to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi

vol. 8, pp. 422-430 (online: 15 December 2014)

Research Articles

Variation of major elements and heavy metals occurrence in hybrid aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx. × P. tremula L.) tree rings in marginal land

vol. 13, pp. 24-32 (online: 15 January 2020)

Research Articles

Characterization of two poplar homologs of the GRAS/SCL gene, which encodes a transcription factor putatively associated with salt tolerance

vol. 8, pp. 780-785 (online: 19 May 2015)

Research Articles

Comparison of genetic parameters between optimal and marginal populations of oriental sweet gum on adaptive traits

vol. 11, pp. 510-516 (online: 18 July 2018)

Commentaries & Perspectives

The genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation: the case of forests

vol. 2, pp. 75-76 (online: 10 June 2009)

Research Articles

Seedling emergence capacity and morphological traits are under strong genetic control in the resin tree Pinus oocarpa

vol. 17, pp. 245-251 (online: 16 August 2024)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword