Ambient ozone phytotoxic potential over the Czech forests as assessed by AOT40

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 5, Issue 3, Pages 153-162 (2012)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor0617-005

Published: Jun 25, 2012 - Copyright © 2012 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Ambient ozone (O3) represents one of the most prominent air pollution problems in Europe. We present an analysis on O3 with respect to its phytotoxic potential over Czech forests between 1994 and 2008. The phytotoxic potential is estimated based on the exposure index AOT40 for forests calculated from real-time monitoring data at 24 rural sites. Our results indicate high phytotoxic potential for most of the Czech Republic (CR) with considerable inter-annual and spatial variability. The highest AOT40 values were 38-39 ppm·h. The critical level for forest protection (5 ppm·h) was usually exceeded early in the growing season, generally in May. In years with meteorological conditions conducive to ozone formation, the critical level was exceeded by 5-7 folds as compared to years with non-conducive conditions; nevertheless, all sites consistently exceeded the critical level since 1994. In the extremely hot and dry year 2003, the critical level for forests was exceeded over 31 % of the Czech forested area. More research is needed to translate these exceedances into forest injury in the CR.

Keywords

Introduction

Ambient ozone (O3) has been a widely studied air pollutant for many years due to its potential toxicity for all living organisms ([16], [6], [31]). It is an important gas playing a key role in atmospheric chemistry ([47]). It contributes to the oxidative power of atmosphere which is essential for scavenging many pollutants from the air. Moreover, due to its absorption-radiation abilities, O3 is an important greenhouse gas ([49], [30]). There are important mutual interactions between O3 and climate change ([33]), which are not fully understood yet. The urgent need to address the knowledge gaps in interactions between air pollution, climate change and forests has been recently stressed ([48], [41]).

Ozone represents one of the most prominent air pollution problems in Europe ([9], [15]). Environmental O3 quality standards are exceeded over vast areas of Europe ([22], [23]). Due to its phytotoxicity, O3 is still considered to be the most important air pollutant for forests ([45]). Due to the fact that O3 is a secondary pollutant formed from precursors during complex photochemical reactions and to the highly non-linear nature of O3 chemistry, it is and will be very difficult to decrease its ambient concentrations ([47]).

Comparison of O3 levels with those measured a century ago indicates that current levels have increased by approximately two times. European measurements between 1850 and 1900 were found to be in the range of 17-23 ppb ([4]). Modern day annual average background O3 concentrations over the mid-latitudes of the northern Hemisphere range between approximately 20-45 ppb, with variability influenced by geographic location, altitude and extent of anthropogenic impacts ([55]). Generally, three types of patterns in ambient O3 have been apparent recently: (1) an increase in the extent of O3 impact and the forest areas at risk; (2) a decrease in maximum 1-h O3 concentrations, at least in the northern hemisphere countries which have introduced O3 precursor control programs; and (3) an increase in background O3 concentrations over much of the world ([46]). It is not an easy task to assess the time trends of O3: the inter-annual variability is fairly high, so that long time series, which mostly are not available ([34]), are needed to detect trends.

In the Czech Republic (CR), ambient air pollution has been perceived as a major environmental problem since the 1950s, particularly due to extremely high emissions of SO2 and particulate matter from large power-generating sources ([42]). Pollution in the form of surface O3 was recognized as an issue as late as in the 1990s. Its levels are regularly measured within the framework of a national ambient air quality network run by the Czech Hydrometeorological Institute (CHMI) since 1993. Ozone levels are relatively high, and the limit values ([13]) over vast regions are frequently exceeded ([25]). Mean O3 concentrations during the growing season at rural sites range between 30 and 45 ppb in years with low O3 levels (as in 2001 and 2008) and between 35 and 60 ppb in years abundant in O3 (as in 2003). Peak 1-h mean O3 concentrations reached 110 ppb in 2003, 90 ppb in other years ([29]).

Based on long term real-time monitoring, we present an analysis of O3 time trends and spatial variability with respect to its phytotoxic potential over Czech forests between 1994 and 2008. Out of the two approaches (concentration-based and flux-based) developed for O3 risk assessment by UN/ECE ([54]), we used the concentration-based approach and applied the exposure index AOT40. We are fully aware of increasing number of studies promoting the flux approach as more scientifically sound (e.g., [1], [40], [53]) and of numerous criticisms of AOT40 concept and robustness (e.g., [50]). Moreover, O3 stomatal flux based indexes are reported to outperform AOT40 for explaining the biological effects such as biomass reduction and leaf visible injury ([36]). From a practical point of view, however, it is obvious that the exposure index has the advantage of relative simplicity, and in regions which are not under stress by drought - which is generally the case of the Czech mountain forests - the areas at risk indicated by exposure index and stomatal flux are not likely to differ substantially. However, even in Japan, where annual precipitation is usually very elevated, the flux approach was recommended when VPD is a limiting factor to stomatal uptake ([24]). The AOT40 has an advantage of relatively simple calculation based on ambient O3 concentration data, while modeling of stomatal flux is much more complicated ([53]). Modeling of stomatal flux needs O3 concentrations and data for stomatal conductance to be measured or modeled. In case the measured data are not available (which is the case for the CR), we are likely to introduce large uncertainties into the calculation. The shortcomings encountered in modeling O3 flux are discussed by Tuovinen et al. ([53]).

Methods

Ozone data

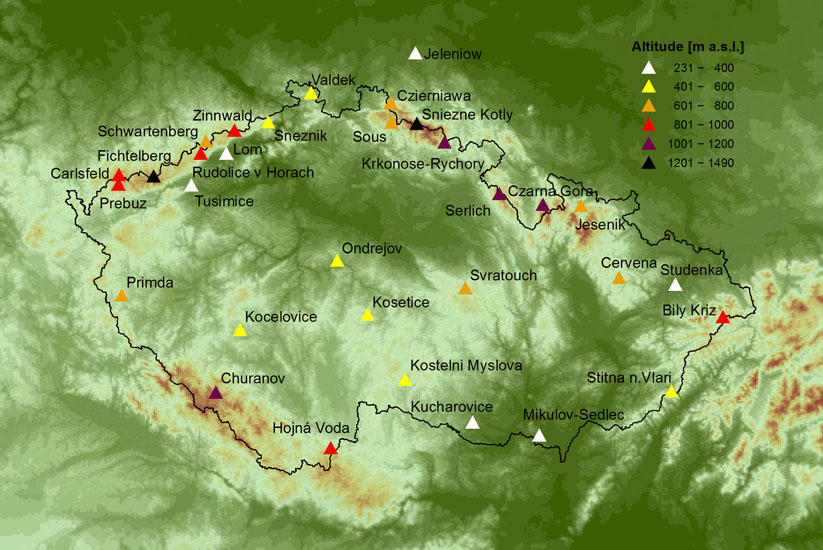

For our analysis, we used the data measured within the framework of the nation-wide ambient air quality monitoring network operated by the Czech Hydrometeorological Institute (CHMI). Ambient O3 monitoring over the CR has evolved significantly since its beginning in 1993. The number of sites within this network has largely increased from an original 16 in 1993 to 55 presently covering rural, mountain and urban areas ([43]). The ambient O3 concentrations were measured by real-time analyzers (Thermo Environmental Instruments TEI, M49) using UV-absorbance, a reference method in the EC ([13]). Standard procedures for quality control and quality assurance ([13]) were applied. We only considered sites with relatively large spatial representativeness, i.e., those classified as rural according to the EoI classification ([12]). Overall, we used 24 Czech sites. For mapping purposes, four additional German and four Polish sites were included (Tab. 1, Fig. 1).

Tab. 1 - Sites used for the analysis ranked according to decreasing altitude.

| Country | Site Name | Site Identifier (ID) |

Altitude (m a. s. l.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic |

Churanov | 1 | 1118 |

| Serlich | 2 | 1011 | |

| Krkonose-Rychory | 3 | 1001 | |

| Prebuz | 4 | 904 | |

| Bily Kriz | 5 | 890 | |

| Rudolice v Horach | 6 | 840 | |

| Hojna Voda | 7 | 818 | |

| Sous | 8 | 771 | |

| Cervena | 9 | 749 | |

| Primda | 10 | 740 | |

| Svratouch | 11 | 735 | |

| Jesenik | 12 | 625 | |

| Stitna n. Vlari | 13 | 600 | |

| Sneznik | 14 | 590 | |

| Kostelni Myslova | 15 | 569 | |

| Kosetice | 16 | 535 | |

| Kocelovice | 17 | 519 | |

| Ondrejov | 18 | 514 | |

| Valdek | 19 | 438 | |

| Kucharovice | 20 | 334 | |

| Tusimice | 21 | 322 | |

| Lom | 22 | 265 | |

| Mikulov-Sedlec | 23 | 245 | |

| Studenka | 24 | 231 | |

| Poland | Sniezne Kotly | 25 | 1490 |

| Czarna Gora | 26 | 1133 | |

| Czierniawa | 27 | 645 | |

| Jeleniow | 28 | 244 | |

| Germany | Fichtelberg | 29 | 1213 |

| Carlsfeld | 30 | 896 | |

| Zinnwald | 31 | 877 | |

| Schwartenberg | 32 | 787 |

Exposure index AOT40Forest

We analyzed the annual trends for selected sites representing the principal Czech mountain regions (1. Churanov - the Sumava Mts., 3. Krkonose-Rychory - the Krkonose Mts., 5. Bily Kriz - the Beskydy Mts., 6. Rudolice v Horach - the Krusne hory Mts., 8. Sous - the Jizerske hory Mts., 12. Jesenik - the Jeseniky Mts.), a regional site considered to represent the CR background (16. Kosetice - the Czech-Moravian Highlands), and a regional site representing the relatively warm lowlands in Southern Moravia (23. Mikulov-Sedlec). For the assessment of ambient ozone phytotoxic potential for forests, we applied the AOT40 approach ([19], [54]). The exposure index AOT40 was calculated according to eqn. 1 (see below). For practical reasons, we considered the daylight hours between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. Central European Time ([13]).

where cijk is the ground-level O3 concentration measured in the i-th month, j-th day and k-th hour; p is the threshold concentration (40 ppb); V is a set of the months of the growing season (April-September); D is a set of daylight hours, defined as those hours with a mean global radiation of 50 W m-2 or greater; and n is the number of days in the month.

Tab. 2 - Data coverage for calculating AOT40Forest expressed as percentage of 1-h mean O3 concentrations available over the growing season (1.4-30.9). The site ID corresponds to the site name in Tab. 1.

| Country | Station ID | Data coverage (%) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | ||

| Czech Republic |

1 | - | 70 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 96 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 100 |

| 2 | - | 33 | 94 | 93 | 94 | 92 | 93 | 98 | 96 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 100 | |

| 3 | - | - | 96 | 87 | 98 | 98 | 92 | 92 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 82 | 89 | 98 | 100 | |

| 4 | 61 | 91 | 99 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 97 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 96 | 99 | 99 | |

| 5 | 97 | 97 | 88 | 96 | 93 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 97 | 100 | 99 | 99 | |

| 6 | - | - | 98 | 98 | 98 | 90 | 99 | 100 | 98 | 98 | 97 | 97 | 93 | 100 | 100 | |

| 7 | - | 99 | 82 | 91 | 88 | 99 | 99 | 92 | 96 | 90 | 98 | 100 | 96 | 99 | 100 | |

| 8 | 88 | 99 | 94 | 97 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 97 | 95 | 96 | 99 | 97 | 97 | |

| 9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 99 | 99 | 96 | 88 | 98 | |

| 10 | - | 81 | 99 | 97 | 98 | 95 | 93 | 98 | 94 | 97 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| 11 | 90 | 88 | 99 | 85 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 96 | 96 | 81 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 100 | |

| 12 | - | 99 | 94 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 97 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 96 | 100 | |

| 13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 91 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 99 | |

| 14 | - | 95 | 98 | 99 | 96 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 32 | 98 | 98 | 100 | 100 | |

| 15 | - | - | - | 94 | 98 | 100 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 78 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | |

| 16 | 92 | 94 | 96 | 99 | 99 | 93 | 100 | 97 | 98 | 100 | 99 | 99 | 96 | 100 | 100 | |

| 17 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 98 | 98 | 97 | 100 | 100 | |

| 18 | 75 | 98 | 90 | 86 | 94 | 100 | 95 | 97 | 97 | 96 | 91 | 95 | 99 | 100 | 100 | |

| 19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 98 | 81 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 97 | |

| 20 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 95 | 99 | 100 | 99 | |

| 21 | 70 | 94 | 96 | 91 | 100 | 97 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 100 | 100 | |

| 22 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 99 | 100 | 100 | 99 | |

| 23 | - | - | 100 | 100 | 96 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 92 | 97 | 99 | 100 | |

| 24 | - | - | - | - | 95 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Poland | 25 | - | - | - | 80 | 95 | 61 | 76 | 48 | 77 | 63 | 65 | 90 | 93 | 94 | 45 |

| 26 | - | - | - | - | 98 | 99 | 93 | 48 | 96 | 92 | 92 | 94 | 99 | 87 | 96 | |

| 27 | - | - | - | 93 | 89 | 75 | 87 | 48 | 98 | 88 | 92 | 69 | 98 | 99 | 95 | |

| 28 | 95 | 93 | 96 | - | - | - | - | - | 94 | 87 | 84 | 96 | 93 | 100 | 100 | |

| Germany | 29 | - | - | - | 88 | 90 | 97 | 96 | 98 | 93 | 92 | 91 | 16 | 96 | 98 | 96 |

| 30 | - | - | 75 | 95 | 97 | 95 | 97 | 97 | 93 | 92 | - | 16 | 99 | 100 | 100 | |

| 31 | - | - | 85 | 94 | 96 | 96 | 91 | 95 | 93 | 95 | - | 16 | 99 | 97 | 99 | |

| 32 | - | - | - | - | 95 | 94 | 92 | 94 | 90 | 95 | - | 16 | 99 | 99 | 99 | |

We carefully checked the data coverage for calculating AOT40. When all possible data were not available for calculation of the AOT40 due to monitoring gaps (Tab. 2), we used the correction factor recommended by EC ([12] - eqn. 2):

where a is the total possible number of hours, and b is the number of measured hourly values.

AOT40Forest spatial pattern

The spatial distribution of AOT40Forest was carried out for three years: 2003, 2006 and 2007. We selected 2003 due to its exceptional meteorological conditions (extremely high temperatures spanning long durations), 2006 as an example of a year with high O3 exposures, and 2007, in contrast, as an example of a year with low O3 exposures during the growing season.

For mapping, we used a linear regression model with subsequent IDW (Inverse Distance Weighting) interpolation of the residuals. AOT40 calculated for the monitoring sites was used as a dependent variable for the regression model. Orography (altitude) was used as an independent variable. For the spatial interpolation of the residuals, we used the deterministic method IDW included in ArcGIS Geostatistical Analyst ([35]). The IDW spatial interpolation technique (e.g., [32]) estimates the cell values using a weighted linear combination of values measured at several neighborhood sites, where the weight is an inverse function of the distance, according to the following equation (eqn. 3):

where Z(s0) is the interpolated grid value; Z(si) is the neighboring data point; h0i is the distance between the grid node and the data point; β is the weighting power (the Power parameter); and n is the number of measuring points.

Maps were prepared at resolution 1x1 km. The digital map of Czech forests produced from the European digital land use map (Corine Land Cover 2000 - ⇒ http://etc-lusi.eionet.europa.eu/CLC2000) was used. A spatial categorization of AOT40 was carried out only for forested areas, which form about 33 % of the Czech territory. For interpolation in border areas, we used data from four German sites for the region of the Krusne hory Mts. and four Polish sites for the northern part of the CR. The spatial distribution of the sites was surprisingly even in altitude (Tab. 3); in contrast, it was uneven regarding the geographical distribution (Fig. 1). The sites were concentrated mostly in mountain areas; the densest network was in the Krusne hory Mts., i.e., in the north-west.

Tab. 3 - Spatial distribution of the monitoring sites (ranked according to the altitude) used for O3 exposure mapping.

| Altitude (m a.s.l.) |

Number of Czech sites |

Total number of sites (including the sites abroad used for border analysis) |

|---|---|---|

| 231-400 | 5 | 6 |

| 401-600 | 7 | 7 |

| 601-800 | 5 | 7 |

| 801-1000 | 4 | 6 |

| 1001-1200 | 3 | 4 |

| 1201-1490 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 24 | 32 |

Ozone precursor data

The data on emission of NOx, VOC, CO were taken from the Register of Emissions and Air Pollution Sources (REZZO), the Czech emission inventory database run by CHMI. REZZO includes information on anthropogenic sources of air pollution, both stationary (categorized as extra large, large, medium and local) and mobile ([43]). The data on emissions of CH4 were taken from the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Report (NIR) of the CR ([18]) and these include both anthropogenic and natural sources.

Temperature data

We used the data measured at climatological stations run by the CHMI. Manual climatic measurements were taken by a station thermometer in a standard thermometer screen 2 m above-ground at climatological observation times, i.e., 7 a.m., 2 p.m. and 9 p.m. local mean solar time (LMST). Seasonal mean temperature was calculated based on daily mean temperatures. Daily mean temperature was calculated as an average of the temperatures at the observation times, where the evening observation was used twice. Seasonal mean temperature was calculated from all available stations which had records for the relevant year, i.e., we used about 200 stations per year ([52]).

Results

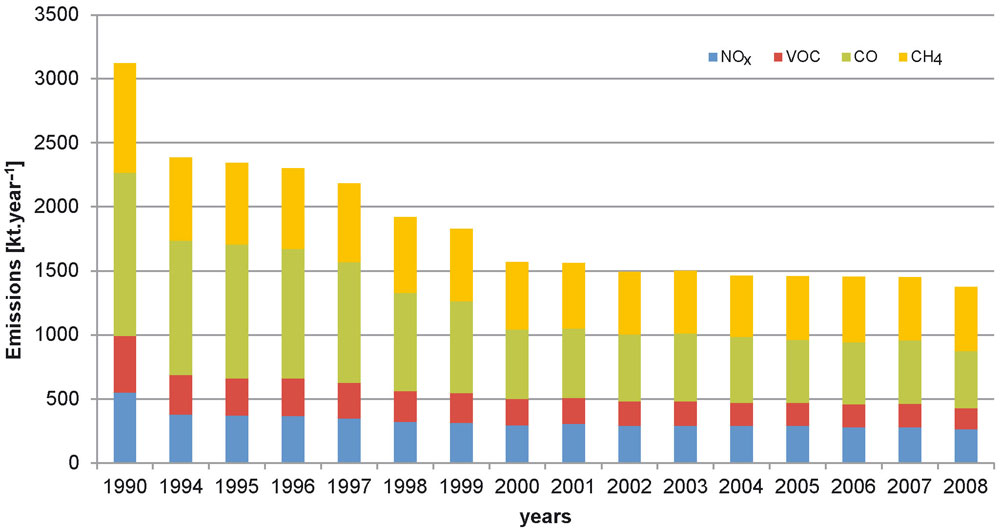

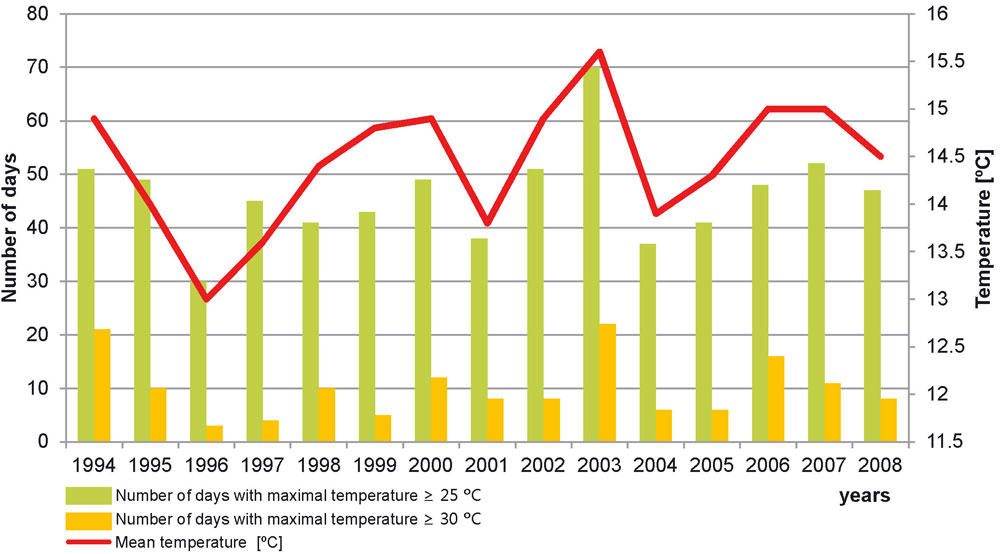

Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 summarize the trends of factors which substantially influence ambient O3 levels. Emission of O3 precursors from Czech anthropogenic sources between 1990 and 2008 decreased by 52 % for NOx, by 63 % for non-methane VOCs, by 65 % for CO, and by 42 % for CH4. For the period under consideration, i.e., 1994-2008, the emission of NOx decreased by 30 %, non-methane VOCs by 47 %, CO by 58 %, and CH4 by 23 %. Though somewhat hidden in a seasonal mean, the air temperature variability was fairly high. In 2003, for example, the temperature in the CR was 4 °C and 3.6 °C above the average in July and August, respectively.

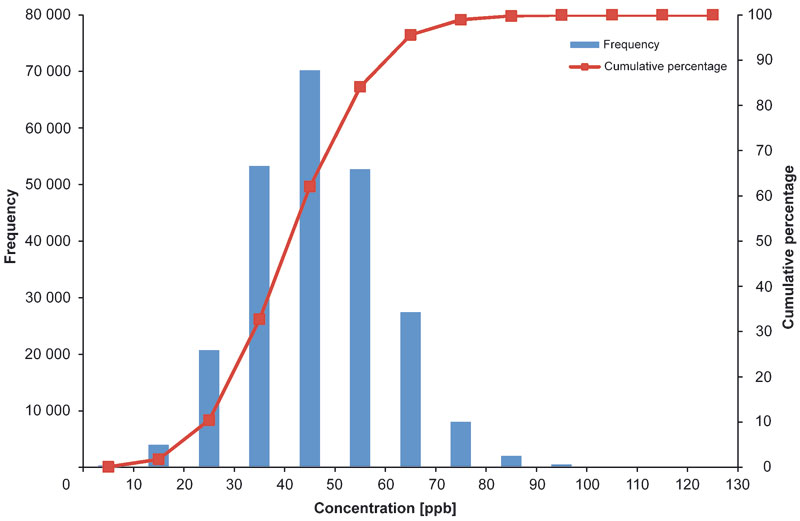

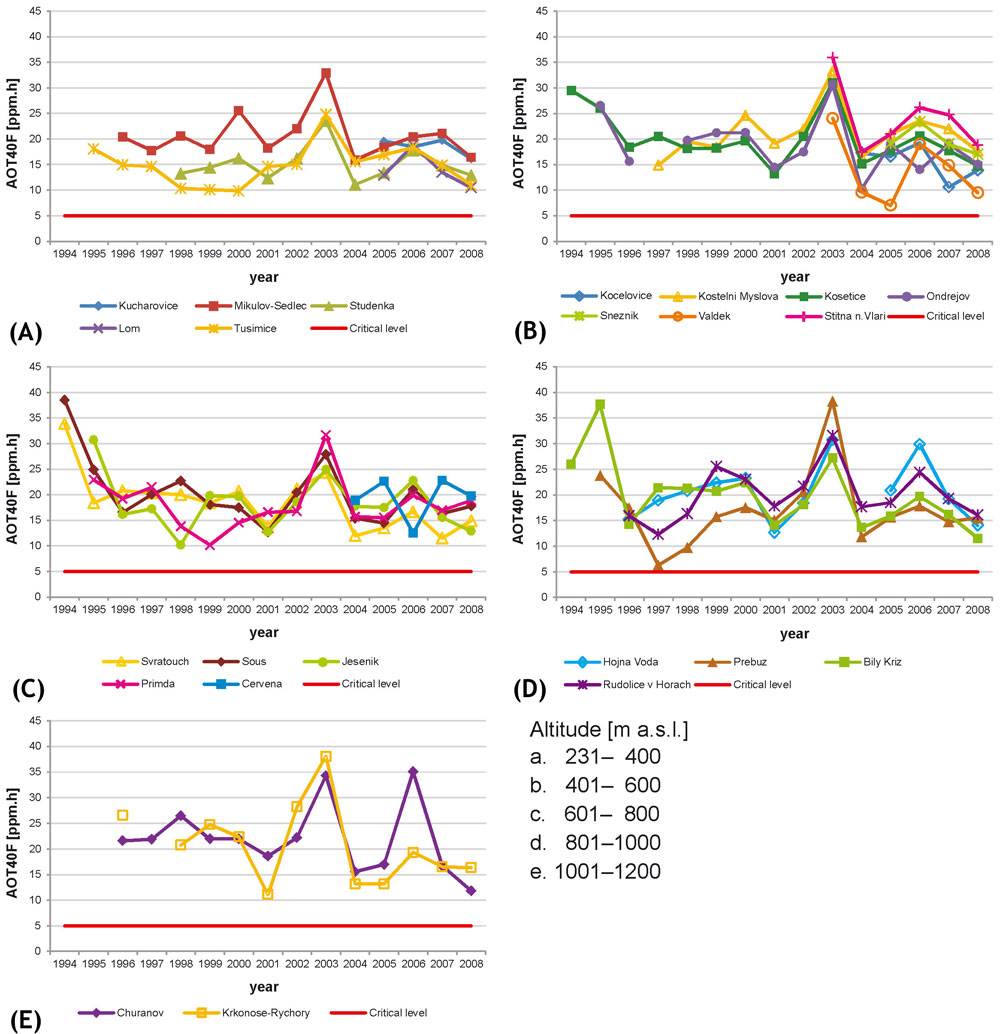

The distribution of 1-h mean O3 concentrations at selected rural sites (indicated as 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 12, 16, 23 - see Tab. 1) in the CR for the period under consideration is summarized by a histogram showing that about 70 % of 1-h mean O3 concentrations were above 40 ppb (Fig. 4). The AOT40 Forest trends for different altitudinal layers are presented in Fig. 5. The AOT40 values for Czech rural sites clearly show that the year-to-year variability was considerable. The critical level of 5 ppm·h ([54]) was exceeded every year at all Czech rural sites. In years with abundant O3, the critical level was exceeded 5-7.5 times (2003). The highest AOT40 values were recorded at the Sous site (39 ppm·h in 1994), Prebuz and Krkonose-Rychory sites (38 ppm·h in 1994), and Bily Kriz (37.7 ppm·h in 1995) in the North. Apart from these mountain sites, fairly high AOT40 was recorded also in lower altitude at the Mikulov site (34 ppm·h in 2003).

Fig. 4 - Histogram of 1-h mean O3 concentrations at selected rural sites (indicated as 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 12, 16, 23) in the CR, 1994-2008.

Fig. 5 - AOT40 at rural sites in the CR, 1994-2008, at several altitudinal layers. Current critical level is 5 ppmh AOT40Forest as set by UN/ECE ([54]).

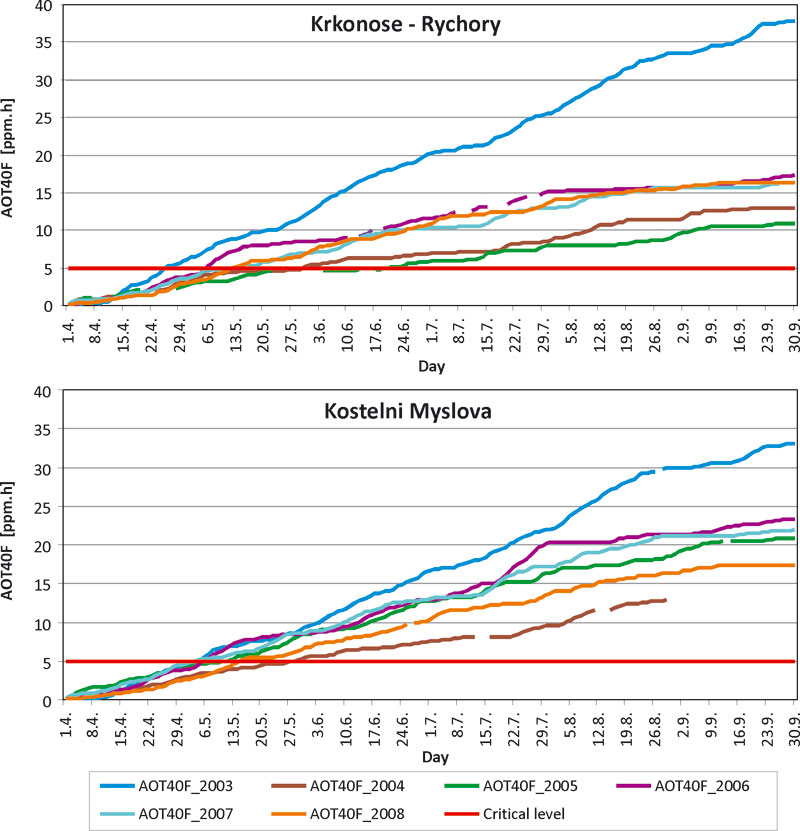

The annual trend of AOT40 differed depending on the meteorological conditions. The critical level of 5 ppm·h was usually reached in the beginning of the growing season (Tab. 4), with few exceptions. As an example, we present the accumulation of AOT40 over the growing seasons 2003-2008 at two sites: a mountain site (3. Krkonose-Rychory) and a rural site situated at a medium altitude (15. Kostelni Myslova - Fig. 6). Rapid AOT40 rise was recorded in 2003, when the critical level of 5 ppm·h at the Krkonose-Rychory site was reached as early as before the end of April and at the Kostelni Myslova site in the beginning of May. Nevertheless, even in the years with meteorological situations not conducive to O3 formation, the critical level of 5 ppm·h was usually reached during May.

Tab. 4 - Average day of the year (DOY) when the critical level of 5 ppmh was exceeded in the 1994-2008 growing seasons at selected rural sites.

| Year | Site ID | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 23 | Average | |

| 1994 | - | - | 5.5 | - | - | - | 16.5 | - | 10.5 |

| 1995 | - | - | 23.4 | - | 12.5 | 6.5 | 24.5 | - | 8.5 |

| 1996 | 21.4 | 17.4 | - | 27.4 | 21.4 | 26.4 | 2.5 | 28.4 | 26.4 |

| 1997 | 12.5 | 12.6. | 14.5 | 29.5 | 17.5 | 15.5 | 16.5 | 19.5 | 18.5 |

| 1998 | 10.5 | 25.5 | 9.5 | - | 8.5 | 21.6 | 12.5 | 10.5 | 20.5 |

| 1999 | 30.4 | 22.5 | 8.5 | 18.5 | 17.5 | 13.5 | 19.5 | 28.5 | 15.5 |

| 2000 | 7.5 | 30.4 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 5.5 |

| 2001 | 20.5 | 14.5 | 24.5 | 23.5 | 25.5 | 25.5 | 9.6 | 23.5 | 27.5 |

| 2002 | 9.5 | 7.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 12.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 21.5 | 14.5 |

| 2003 | 29.4 | 26.4 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 5.5 |

| 2004 | 26.5 | 31.5 | 27.5 | 31.5 | 1.6 | 13.5 | 7.6 | 30.5 | 28.5 |

| 2005 | 12.5 | - | 8.5 | 16.5 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 16.5 | 17.5 | 9.5 |

| 2006 | 18.4. | 6.5 | 8.5 | 12.5 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 8.5 |

| 2007 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 19.5 | 5.5 | 13.5 | 5.5 | 11.5 | 13.5 | 10.5 |

| 2008 | 17.5 | 13.5 | 3.6 | 21.5 | 14.5 | 16.5 | 25.5 | 30.5 | 22.5 |

| Average | 8.5 | 13.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 11.5 | 13.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 13.5 |

Fig. 6 - Annual trend of AOT40 at Krkonoše-Rýchory (1001 m a.s.l.) and Kostelní Myslová (569 m a.s.l.), 2003-2008 growing seasons.

Fig. 7 shows the spatial distribution of AOT40 in 2003 when the exceedances of 5 ppm·h were the highest ever recorded. The critical level was exceeded more than 6 times over one third of the Czech forested area. The highest values were recorded over the border mountains - the Krkonose, the western part of the Krusne hory Mts., the Cesky les, the Sumava, and also inland over the Czech-Moravian Upplands (Ceskomoravska Vysocina) and the Brdy. Fig. 8 shows the spatial distribution of AOT40 in 2006 which belonged to the years abundant in O3 (though lower as compared to the extreme year of 2003) as a consequence of a very warm and dry summer in Central Europe. In contrast to 2003, the relative share of forested area with AOT40 above 30 ppm·h was < 3 %. The highest values were recorded in the South, in the Sumava and Novohradske hory Mts. Fig. 9 shows the year 2007 with even lower O3 levels. Still, 78 % of the Czech forested area experienced an exceedance of the critical level by a factor of 3-4.

Discussion

The crucial factors for ambient O3 concentrations are emission of precursors and prevailing meteorological conditions. Solar intensity is of particular importance. Hot sunny calm weather leads to high O3 concentrations. High temperature, high solar intensity, low wind speed, low atmospheric humidity and absence of precipitation are factors generally considered as favorable for photochemical O3 formation ([47]). While anthropogenic O3 precursor emissions in Europe have decreased ([14]), the air temperature tends to increase. Observational evidence from all continents shows that many natural systems are being affected by regional climate changes, particularly temperature increases ([30]). For CR, Tolasz et al. ([52]) reported a statistically significant temperature increase for the period 1961-2000: annual average temperature increases by 0.028 ºC year-1 (R2 = 0.195) and growing season average temperature increases by 0.025 ºC year-1 (R2 = 0.151). A similar trend is still observable and we can summarize that the average temperature in the CR increases by 0.3 ºC per decade in the last 50 years (⇒ http://www.chmi.cz/).

Ambient O3 is a regional phenomenon and for its formation the emissions from broader regions are of importance. According to European Environmental Agency (EEA), emissions of the main ambient O3 precursor pollutants have decreased significantly across the EEA region between 1990 and 2009 as follows: NOx by 44 %, non-methane VOCs by 55 %, CO by 62 % and CH4 by 27 % ([15]). These estimates correspond with the trend in the CR, though the O3 precursor emission decrease in the CR was even more pronounced as compared to the EEA region. Though the uncertainties associated with estimated emissions are relatively high, accounting for about 50 % for VOCs and CH4 and 30 % for NOx ([8]), the progress in reducing emissions is obvious. We have to keep in mind, however, that O3 formation changes under differing NOx and VOC regimes ([47]), and tropospheric ozone-forming potential differs for individual precursor gases ([8]).

There is a discrepancy between the substantial cuts in O3 precursor emissions and observed non-decreasing annual average O3 concentrations in Europe. Reasons include increasing inter-continental transport of O3 and its precursors in the northern hemisphere, climate change, biogenic non-methane VOC emission, which are difficult to quantify, and natural fires ([15]).

An inherent property of AOT40 as a cumulative index is that it is very sensitive to the quality of input data. For calculating AOT40Forest, O3 concentrations were measured in real time, thoroughly checked and considered as highly variable; the calculated index, however, is not robust ([50]) and is likely to be burdened by high uncertainty. Consideration of the spatial scale is a crucial issue for air pollution mapping, as stressed by Diem ([11]). A spatial resolution of 1 x 1 km, as used in our mapping, is detailed enough, provides consistent results, and is considered appropriate for a country-scale mapping ([20]). The relative uncertainty of the AOT40Forest maps analyzed by cross-validation and expressed by the root mean square error (RMSE) was about 20 % as shown earlier by Hunová et al. ([26]) in a comparison of 11 different interpolation approaches for ambient O3 mapping. The relative uncertainty of AOT40Forest maps is worse when compared to maps of seasonal mean O3 concentrations, but it is still acceptable.

A similar approach for O3 phytotoxic potential assessment based on O3 concentrations measured in real time and interpolation of calculated AOT40Forest values was used for United Kingdom by Coyle et al. ([7]), and for EU by Horálek et al. ([22], [23]). Different interpolation techniques were used in these studies, but approach and scale were similar. For Italy, where monitoring network does not adequately cover all the territory, De Marco ([10]) applied an integrated assessment model (RAINS-Italy) for developing a map of AOT40Forest.

The highest O3 concentrations in Europe are observed in the Mediterranean countries ([15]). Nevertheless, O3 concentrations measured throughout central Europe ([40]) including the CR are also very high. The AOT40Forest values that we calculated for some Czech sites are comparable to values reported for Italy ([44]).

Our analysis of real-time O3 data recorded during 1994-2008 within the framework of the Czech national ambient air quality monitoring network shows that O3 exposure over the Czech forested areas still remains fairly high and varies considerably in time and space. We assume that in the Czech rural regions, where average hourly O3 concentrations during the growing season are generally significantly higher than 40 ppb ([25], [27]) and, in particular, under optimal nutrient regime and water availability, the AOT40 exposure index provides a reasonable estimation of the risk areas. This assumption would not apply for the year 2003, an extreme year regarding meteorology ([37]), when the high O3 concentrations were coupled with extreme drought affecting stomatal conductance.

As stressed earlier by many authors, it is necessary to observe plant effects to give biological significance and meaning to O3 standards ([38]). Visible ozone injury is assessed regularly at selected plots within the forest condition monitoring in the CR by Forestry and Game Management Research Institute ([3]). Despite the high O3 levels measured over the CR, no serious damage to vegetation attributable to O3 has been reported so far. In a case study carried out in the Jizerske hory Mts. in 2006 and 2007 at five sites situated in the altitudes 900-1000 m a.s.l., the leaves of 22 plant species were assessed for ozone-like visible symptoms according to UN/ECE ([54]). Though injury was found, the extent of visible symptoms was much less than assumed considering the recorded O3 exposure ([39]). Moreover, after verification of symptoms by the Ozone Validation Centre for Central Europe ([21]), visible injury was confirmed as O3-induced on the leaves of only two species, Fagus sylvatica and Rubus idaeus ([28]). This is in agreement with earlier reports from many other authors (e.g., [17], [40], [56], [2], [5]), that the O3 exposure is rather inconsistent with observed ozone injury. Moreover, the assumption that higher ambient O3 exposure results in higher contents of malondialdehyde (MDA) as a product of lipid peroxidation in Picea abies needles was not supported by a study in real forest stands of three Czech mountain areas - the Krkonose, Krusne hory and Jizerske hory Mts. in 1994-2006 ([29]). In contrast, Srámek et al. ([51]) indicated an impact of O3 on beech (Fagus sylvatica) as assessed by the quality and quantity of epicuticular waxes and content of MDA. Furthermore, Zapletal et al. ([57]) reported that ambient O3 reduces net ecosystem production in a Norway spruce (Picea abies) stand in the CR, though spruce as most of the conifers is considered as a relatively ozone-tolerant species ([54]). Thus, so-far reported impacts of O3 on vegetation in the CR are equivocal and further effort is needed to clarify the issue and translate O3 exposure to biological impacts on CR forests.

Conclusions

Our analysis of real-time ambient O3 measurements at Czech rural sites recorded over the last 15 years shows that O3 exposure over the Czech forested areas still remains fairly high and varies considerably in time and space. All sites consistently exceeded the critical level of 5 ppm·h AOT40Forest since 1994, with peak values reaching 38-39 ppm·h at few sites in different years. Existing studies on ambient O3 biological effects on Czech forests are equivocal and more effort is needed to explore the O3 impacts. Regarding environmental protection the effort should be focused on the most sensitive forest species.

Acknowledgments

The results of this paper were presented at the COST Action FP0903 conference “Ozone, climate change and forests” held in Prague in June 2011. CHMI provided the ozone data used for the analysis. We are grateful to LfULG and IMGW for providing the data from German and Polish sites. We thank our colleague Linton Corbet, who revised the English for style and commented the final version of the manuscript. The authors highly appreciate detailed comments of an anonymous reviewer on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

M Schreiberová

Czech Hydrometeorological Institute, Na Šabatce 17, 143 06 Prague 4 - Komorany (Czech Republic)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Hunová I, Schreiberová M (2012). Ambient ozone phytotoxic potential over the Czech forests as assessed by AOT40. iForest 5: 153-162. - doi: 10.3832/ifor0617-005

Academic Editor

Elena Paoletti

Paper history

Received: Nov 29, 2011

Accepted: May 11, 2012

First online: Jun 25, 2012

Publication Date: Jun 29, 2012

Publication Time: 1.50 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2012

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 57323

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 47469

Abstract Page Views: 3839

PDF Downloads: 4188

Citation/Reference Downloads: 28

XML Downloads: 1799

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 5008

Overall contacts: 57323

Avg. contacts per week: 80.12

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2012): 20

Average cites per year: 1.43

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

A comparison between stomatal ozone uptake and AOT40 of deciduous trees in Japan

vol. 4, pp. 128-135 (online: 01 June 2011)

Research Articles

Effects of abiotic stress on gene transcription in European beech: ozone affects ethylene biosynthesis in saplings of Fagus sylvatica L.

vol. 2, pp. 114-118 (online: 10 June 2009)

Research Articles

Changes in the proteome of juvenile European beech following three years exposure to free-air elevated ozone

vol. 4, pp. 69-76 (online: 05 April 2011)

Research Articles

Soil drench of ethylenediurea (EDU) protects sensitive trees from ozone injury

vol. 4, pp. 66-68 (online: 05 April 2011)

Research Articles

Ozone fumigation effects on the morphology and biomass of Norway spruce (Picea abies L.) saplings

vol. 2, pp. 15-18 (online: 21 January 2009)

Research Articles

Prediction of ozone effects on net ecosystem production of Norway spruce forest

vol. 11, pp. 743-750 (online: 15 November 2018)

Short Communications

Ozone flux modelling for risk assessment: status and research needs

vol. 2, pp. 34-37 (online: 21 January 2009)

Review Papers

Monitoring the effects of air pollution on forest condition in Europe: is crown defoliation an adequate indicator?

vol. 3, pp. 86-88 (online: 15 July 2010)

Technical Reports

Air pollution regulations in Turkey and harmonization with the EU legislation

vol. 4, pp. 181-185 (online: 11 August 2011)

Research Articles

Long-term monitoring of air pollution effects on selected forest ecosystems in the Bucegi-Piatra Craiului and Retezat Mountains, southern Carpathians (Romania)

vol. 4, pp. 49-60 (online: 05 April 2011)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords