The potential of the marula tree, Sclerocarya birrea, (A. Rich.) Horchst subspecies litterfall in enhancing soil fertility and carbon storage in drylands

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 18, Issue 6, Pages 366-374 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor4478-018

Published: Dec 07, 2025 - Copyright © 2025 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

The potential of Sclerocarya birrea subspecies as native trees to improve agricultural productivity and combat global warming through carbon storage has not been fully explored, despite their extensive distribution across global drylands. The objective of this study was to determine the potential of litterfall from Sclerocarya birrea subspecies to improve soil organic carbon (OC) and fertility, and carbon storage in drylands. Leaf and fruit litterfall samples, comprising 18 samples for each subspecies, from nine trees of subspecies birrea, caffra, and multifoliata were collected in Tanzania. Soil samples were collected under and away from the canopies of the selected trees. The soil pH and the concentrations of organic carbon (OC) and nutrients (total Nitrogen - TN, P, K, Ca, Mg, Na, Cu, Zn, Fe, Mn, S) in the soil, fruit, and leaf litterfall were determined using standard laboratory methods of analysis. The results showed that leaf OC in S. birrea subspecies ranged from 41.16% to 43.49%, and TN from 1.01% to 1.19%. The C:N ratio ranged from 34.58% to 41.66% in leaf, and from 52.73% to 75.12% in fruit litterfall. Phosphorus was significantly higher in fruit (0.17-0.20%) than in leaf (0.02-0.04%) for all subspecies. Ca and Mg were higher in leaf litterfall (0.54-0.89% Ca and 0.19-0.27% Mg), than in fruit litterfall (0.08-0.11% Ca and 0.10% Mg). Cu, Fe, and Mn concentrations were significantly higher in fruit, ranging from 11.71 to 31.42 mg kg-1, 214.13 to 400.59 mg kg-1, and 31.42 to 54.77 mg kg-1, respectively, than in leaf with 3.32 to 4.39 mg kg-1, 64.10 to 107.70 mg kg-1, and 16.08 to 18.97 mg kg-1, respectively. Contrastingly, Zn in leaf ranged from 412.97 in multifoliata to 499.78 mg kg-1 in caffra, which was 33 to 46 times higher than in fruit litterfall. Soils under the canopies of subsp. birrea, caffra, and multifoliata had significantly higher OC and K, Na, and S (p < 0.05), and numerically higher concentrations of most nutrients than soils away from the canopies. We concluded that leaf and fruit litterfall of the Sclerocarya birrea subspecies can improve soil fertility and carbon storage in drylands if managed properly.

Keywords

Climate Change, C:N Ratio, Carbon Sequestration, Food Security, Agroforestry, Litterfall Quality, Soil Amendment

Introduction

Innovative agroforestry systems to conserve native trees, improve crop yields, and achieve food security are critical for climate change resilience in African dryland farming systems. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) harbors approximately 13.9 million km2 of drylands that support the livelihoods of more than 425 million people ([6]). About 70 percent of the SSA dryland is used for agriculture, of which 66 percent is for cereal production ([6]). However, the nexus of food insecurity, extreme poverty, and environmental degradation, coupled with low use of inorganic fertilizers, is the most challenging in the drylands of African countries ([18]). Agricultural soils in drylands are characterized by low fertility due to low nitrogen and phosphorus levels, low water-holding capacity, low organic matter content ([47]), and highly variable soil fertility ([38]). Thus, there is a need to find ways to improve soil fertility through agroforestry nutrient cycling using appropriate native tree species to complement fertilizer applications and simultaneously improve land productivity and sustain crop production.

Native trees are acknowledged as an important component of sustainable agriculture ([41]). Native trees have the potential to increase agricultural production by recycling nutrients through litterfall, producing more annual litterfall with higher nutritional quality than exotic species ([49]). Native trees also support ecosystem connectivity, biodiversity conservation, and carbon sequestration ([45]).

Marula tree, Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich.) Horchst, is a drought-tolerant and multipurpose fruit tree indigenous to Africa ([15]). The tree is widely distributed in African drylands and has been introduced outside its native range, including the Negev Desert in Israel ([15], [37]). The species has also been introduced in botanical gardens in the USA, India, Oman, and Australia ([15]), and in China for experimental trials as a commercial crop ([22]). S. birrea has three distinct subspecies, namely, S. birrea subsp. birrea, S. birrea subsp. caffra, and S. birrea subsp. multifoliata ([15]), and all are found in Tanzania ([15], [34]). S. birrea is rarely planted by farmers; instead, it is retained in agricultural fields ([18]). The tree can be integrated into dryland agroforestry systems to maintain soil fertility and support human nutrition, health, and income security ([18]).

Sclerocarya birrea was named “arido-active” tree species due to its ability to continue metabolic activity, including sprouting leaves, during the dry season before rain onset ([44]). Moreover, S. birrea is a keystone tree species that supports a wide range of domestic and wild animal species, including elephants ([13]). In arid and semi-arid savannas where trees are scattered, birds and animals normally seek shelter and food under tree canopies, and consequently act as agents for importing nutrients ([50]). Inorganic N, microbial biomass-C, and nitrogen mineralization of soils under S. birrea canopies were investigated by Diallo et al. ([10]), who showed that concentrations of inorganic N and soil microbial biomass-C were generally higher under the canopies. However, the study was limited to the species level, with no disaggregation of subspecies potential and no information on the potential cycling of other nutrients. Disaggregation of subspecies’ litter nutrient and carbon concentrations is important because the subspecies occur in different ecological regions in Tanzania ([34]) and worldwide ([33]). Thus, their potential to enhance soil fertility and carbon storage will likely vary.

Global drylands have the potential to store about 30% of the world’s carbon stock ([16]). Our previous work estimated suitable areas for S. birrea subspecies as between 3.751.057 km2 and 24.632.452 km2 of Earth’s surface ([33]). Additionally, S. birrea is known for its long lifespan, as evidenced by the subspecies caffra, which has lived for over 200 years ([15]). However, research on the potential of S. birrea subspecies’ litterfall to improve soil organic carbon, fertility, and carbon storage in drylands remains limited. Thus, there is a need to understand S. birrea potential for agroforestry in drylands.

This study was conducted to (i) determine organic carbon and total nitrogen concentration in Sclerocarya birrea subspecies leaf and fruit litterfall, (ii) compare nutrient (macro- and micro-nutrients) concentration variations among S. birrea subspecies litterfall types, and (iii) determine the potential of S. birrea subspecies leaf and fruit litterfall in enhancing soil fertility and carbon storage in drylands of Tanzania. The study’s findings will enhance our understanding of the potential of Sclerocarya birrea subspecies litterfall to improve soil fertility and combat global warming by storing carbon in drylands.

Materials and methods

Description of study areas

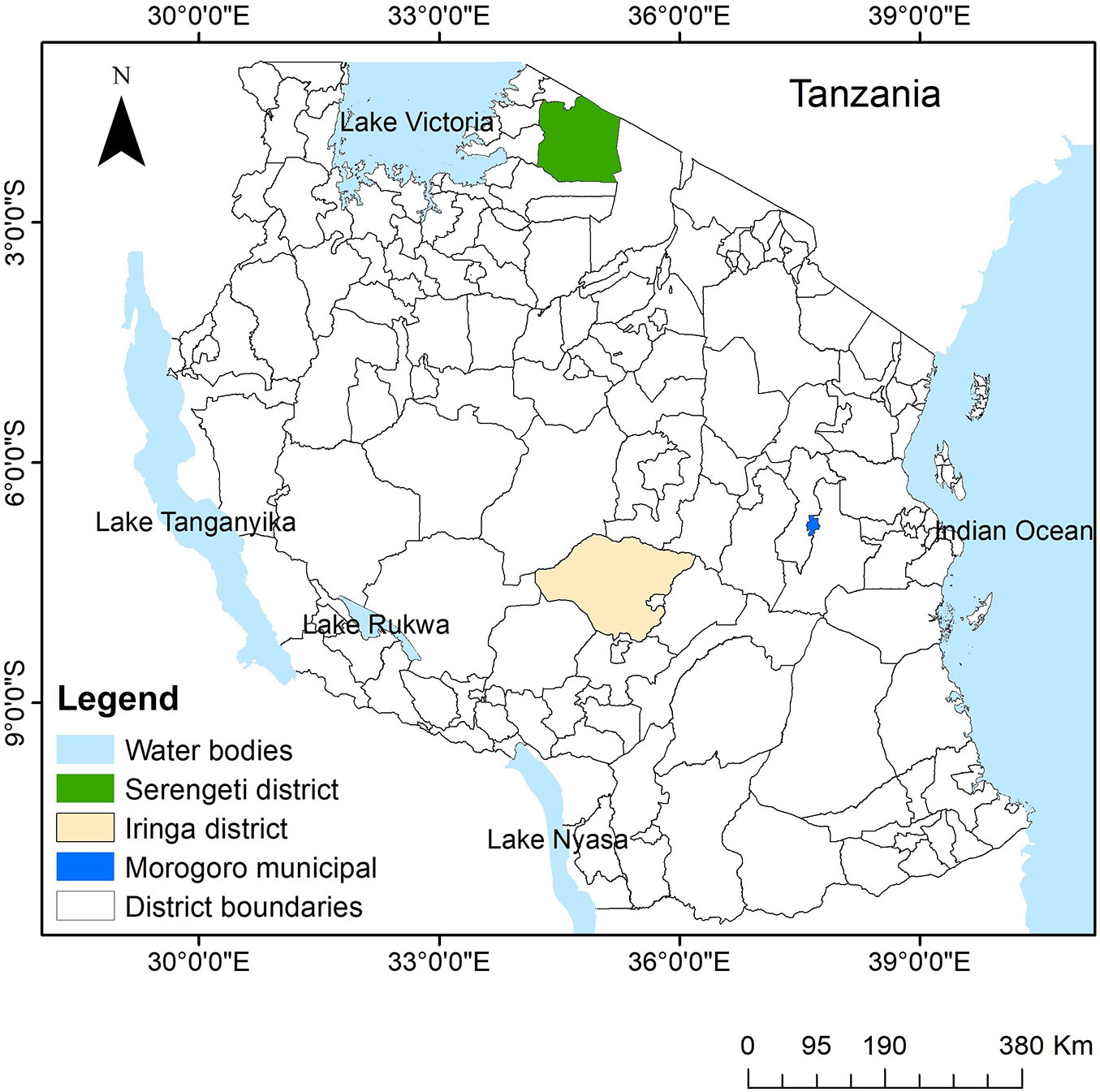

The study was conducted in three districts in Tanzania: (i) the Serengeti district in Mara region; (ii) the Iringa district in Iringa region; and (iii) the Morogoro municipal in Morogoro region (Fig. 1). The salient features and the locations of trees where leaf and fruit litterfall samples were collected are detailed in Tab. S1 (Supplementary material).

Fig. 1 - Map showing the locations of the Serengeti district, Morogoro municipal, and Iringa district, where leaf and fruit litterfall samples of Sclerocarya birrea subsp. birrea, S. birrea subsp. caffra, and S. birrea subsp. multifoliata were collected, respectively.

In the Serengeti district, litterfall was collected in Bonchugu village, located between 01° 30′ S and 02° 40′ S and 34° 15′ E and 35° 30′ E, at altitudes ranging from 1000 to 2300 m a.s.l. The Serengeti district shows a bimodal distribution of rainfall during the year: short rains from October to December and long rains from March to May. The total rainfall in the district ranges from 900 to 1000 mm per year. Temperatures in the Serengeti district range from 15 °C in April to 29 °C in July. The district harbors the Sclerocarya birrea subspecies birrea. The major soil types in the Serengeti district are Ferralic Cambisols and Eutric Planosols (Western Serengeti), Luvic Phaeozems (North-eastern Serengeti), and Luvic Phaeozems, Mollic Solonetzs, and Luvic Chernozems (East Serengeti - [26]).

S. birrea subsp. caffra leaf and fruit litterfall samples were collected in Kiegea village, Morogoro municipal. Morogoro municipal lies between longitudes 37° 34′ 52″ E and 37° 45′ 25″ E and between latitudes 06° 38′ 56″ S and 06° 55′ 8″ S ([12]). The annual rainfall ranges from 600 mm in the lowlands to 1200 mm in the highland plateau. Morogoro receives short, unreliable rainfall between September and December, while long rains occur from February/March to April/May. The mean monthly temperature ranges from 17.48 °C in the mountains to 31.31 °C in river valleys, with an average temperature of 25 °C. The soil of Morogoro municipality originates from a Precambrian basement complex called the Usagaran unit, with high-grade metamorphic rocks including amphibolite, gneiss, and granulites, and a Neogene formation, known for its thick layer of red soil, heavy black clay “mbuga” soil, and alluvium ([31]).

In the Iringa district, leaf and fruit litterfall of S. birrea subsp. multifoliata were collected close to Maliganza village. The Iringa district lies between latitudes 07° 00′ and 08° 30′ S and longitudes 34° 00′ and 37° 00′ E, at an altitude of 800 to 1800 m a.s.l. The rainfall in the district has a unimodal distribution of 600-1000 mm annually, falling from November/December to April/May, and a mean temperature of 15-20 °C. In this district, soils in the lowlands zone are dominated by red/brown loam, which are moderately fertile; the midlands zone is characterized by intermediate clay soils, which are moderately drained and leached; while the highlands zone is characterized by red/yellow, well-drained, and highly weathered and leached clay soils ([48]).

Litterfall and soil sampling

Leaf and fruit litterfall samples were collected from nine randomly selected female trees for each S. birrea subspecies in each study site (Tab. S1 in Supplementary material). Leaf litterfall samples were collected using four traps (60 × 60 cm nets with 2 mm of mesh size) set in the four cardinal directions under the trees’ canopies, which were placed 2 m above the ground. Leaf litterfall samples were collected from March to April for the subspecies birrea in Bonchugu village in Serengeti district, May to June for the subspecies multifoliata in Malinzanga village in Iringa district, and from May to July for the subspecies caffra in Kiegea village, Morogoro Municipal. The leaf litterfall samples from four traps per tree were thoroughly mixed, and a composite sample weighing at least 2 kg was collected and packed in zipped plastic bags.

Fruit samples were collected under the S. birrea subspecies canopies in a 2 × 2 m plot with a tree trunk in the middle. The fruit samples of subsp. birrea were collected in Bonchugu village in March 2020, subspecies caffra and multifoliata were collected in Kiegea and Malinzanga villages, respectively, both in April 2020. Fruit litterfall samples averaging 5 kg were collected from the traps and packed into clean woven polypropylene bags. Overall, a total of 54 fruit and leaf samples, 18 samples (9 fruits and 9 leaves) for each subspecies, were collected from 27 sampled trees of S. birrea subspecies in Tanzania.

Soil samples were collected under each sampled tree, including leaf and fruit samples. Soil samples were collected following a four-compass cardinal direction and composited to constitute one sample per tree. Soil samples were collected at 0-20 cm depth, under (about 1 m from the tree trunk) and away (about 40 m away from the canopy margin) from the tree canopy. Soil samples from each tree were thoroughly mixed, and composite samples weighing at least 0.5 kg were taken and packed in zipped plastic bags. The litterfall (leaf and fruit litterfall) and soil samples were transported and air-dried in a dust-free screen house at the Soil Science laboratory, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania.

Leaf and fruit litterfall, and soil samples preparation

Once at the screen house, the seeds were removed from the fruit samples. The leaf litterfall samples were sorted and sieved in a 5-mm sieve to remove unwanted materials. The leaf and fruit litterfall samples were separately oven-dried to a constant weight at 70 °C, and then weighed. Soil samples were air-dried in a screen house. Separately, leaves and fruit samples were ground to a fine powder using a plant grinder for chemical analyses. The soil samples were ground in a mortar on a clean, hard surface and passed through a 2-mm sieve for chemical analyses.

Laboratory analyses

Leaf and fruit litterfall samples were analyzed for Total Nitrogen (TN), organic carbon (OC), Phosphorus (P), Sulphur (S), Potassium (K), Calcium (Ca), Magnesium (Mg), and Sodium (Na), as well as for micronutrients (Copper - Cu, Iron - Fe, Zinc - Zn, Manganese - Mn) as follows. The TN was determined by using the micro-Kjeldahl digestion method in concentrated sulfuric acid and mixed catalysts, followed by distillation with 40% NaOH and titration with acid ([5]). The OC was determined by using the Walkley and Black dichromate method ([36]). The leaf and fruit litterfall samples were separately digested using the wet digestion method in a microwave digester (Multiwave Pro® 24HVT80, Anton Paar, Australia), and the digests were used to quantify total P, K, Na, Ca, Mg, Zn, Cu, Fe, and Mn. The Na and K concentrations in the digest were determined using a flame photometer ([1]). Total P was determined by UV Spectroscopy after blue color development with ammonium molybdate, as described by Murphy & Riley ([35]). Sulphur concentration was determined by the turbidity method with BaCl2 ([32]) and quantified using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (BioMate™ 6 model, Thermo Fisher, USA). The concentrations of Cu, Zn, Fe, Mg, and Mn were determined by an atomic absorption spectrometer (iCE3300, AA System model, UK - [23]).

Soil samples were subjected to the following analyses. Soil pH was measured with a pH meter at a 1:2.5 soil:water ratio ([30]). Available P was extracted by the Bray-1 method as described by Bray & Kurtz ([4]) followed by blue color development using ammonium molybdate and quantified by using UV Visible Spectrophotometer method ([35]). TN was determined by the micro-Kjeldahl method ([5]), and OC was assessed by the Walkley-Black dichromate method ([36]). Exchangeable bases (Ca, Mg, K, Na) in soil samples were extracted using 1 N ammonium acetate (NH4OAc) leaching solution, buffered at pH 7.0 ([46]), and quantified by AAS for Ca and Mg, flame photometer for K and Na, and CEC by distillation-titration method after displacement of NH4+ of NH4OAc saturation with KCl ([39]). Monocalcium phosphate [Ca(H2PO4)2] solution was used to extract S ([7]), while Zn, Cu, Fe, and Mn were extracted using diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA - [23]) and quantified by AAS.

Statistical analysis

Nutrient concentrations in soils, and Sclerocarya birrea subspecies leaf and fruit litterfall concentration data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA - α = 0.05) to determine the differences in nutrient concentrations between litterfall types (leaves vs. fruits) in each subspecies. When significant differences were found, means were separated by the Least Significant Difference (LSD) at p ≤0.05. To determine the effect of litterfall on soil fertility, an independent-samples t-test was used to assess differences in soil fertility between soils under and away from the canopies of the three S. birrea subspecies. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software v. 9.4 ([43]).

Results

Organic carbon and total nitrogen concentration in the leaf and fruit litterfall

The results showed that the concentration of OC did not differ significantly between leaf and fruit litterfall, ranging from 41.16 ± 0.71% to 43.49 ± 0.61% in leaf litterfall and 42.82 ± 2.02% to 49.57 ± 5.23% in fruit litterfall (Tab. 1); whereas the TN differed significantly between leaf and fruit litterfall (p = 0.0001 to 0.0279 - Tab. 1). TN was higher in the leaf litterfall (1.01 ± 0.01% to 1.19 ± 0.06%) than in the fruit litterfall (0.57 ± 0.07% to 0.94 ± 0.07% - Fig. 2). The leaf litter TN in S. birrea subsp. birrea was 1.19 ± 0.06%, in the caffra subspecies was 1.01 ± 0.01% and in the multifoliata subspecies was 1.14 ± 0.04%. The TN in fruits was 0.94 ± 0.07%, 0.57 ± 0.07%, and 0.79 ± 0.05% for birrea, caffra, and multifoliata subspecies, respectively (Tab. 1). The C:N ratios in the leaf litterfall ranged from 34.58% to 41.66%, and in fruit litterfall ranged from 52.73% to 75.12% (Tab. 1).

Tab. 1 - The organic carbon and total nitrogen content and their ratios in leaf and fruit litterfall of Sclerocarya birrea subspecies in Tanzania. Mean and p-values from analysis of variance (ANOVA) are reported. (df): degree of freedom. Significant (p<0.05) effects are indicated by different letters.

| Litterfall type |

Subsp. birrea | Subsp. caffra | Subsp. multifoliata | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC | TN | C: N | OC | TN | C: N | OC | TN | C: N | |

| Leaf | 41.16 ± 0.71 a | 1.19 ± 0.06 a | 34.58 | 42.08 ± 0.89 a | 1.01 ± 0.01 a | 41.66 | 43.49 ± 0.61 a | 1.14 ± 0.04 a | 38.14 |

| Fruit | 49.57 ± 5.23 a | 0.94 ± 0.07 b | 52.73 | 42.82 ± 2.02 a | 0.57 ± 0.07 b | 75.12 | 44.87 ± 3.37 a | 0.79 ± 0.05 b | 56.79 |

| p-value (df=1) | 0.1309 | 0.0279 | - | 0.7425 | <.0001 | - | 0.6936 | <.0001 | - |

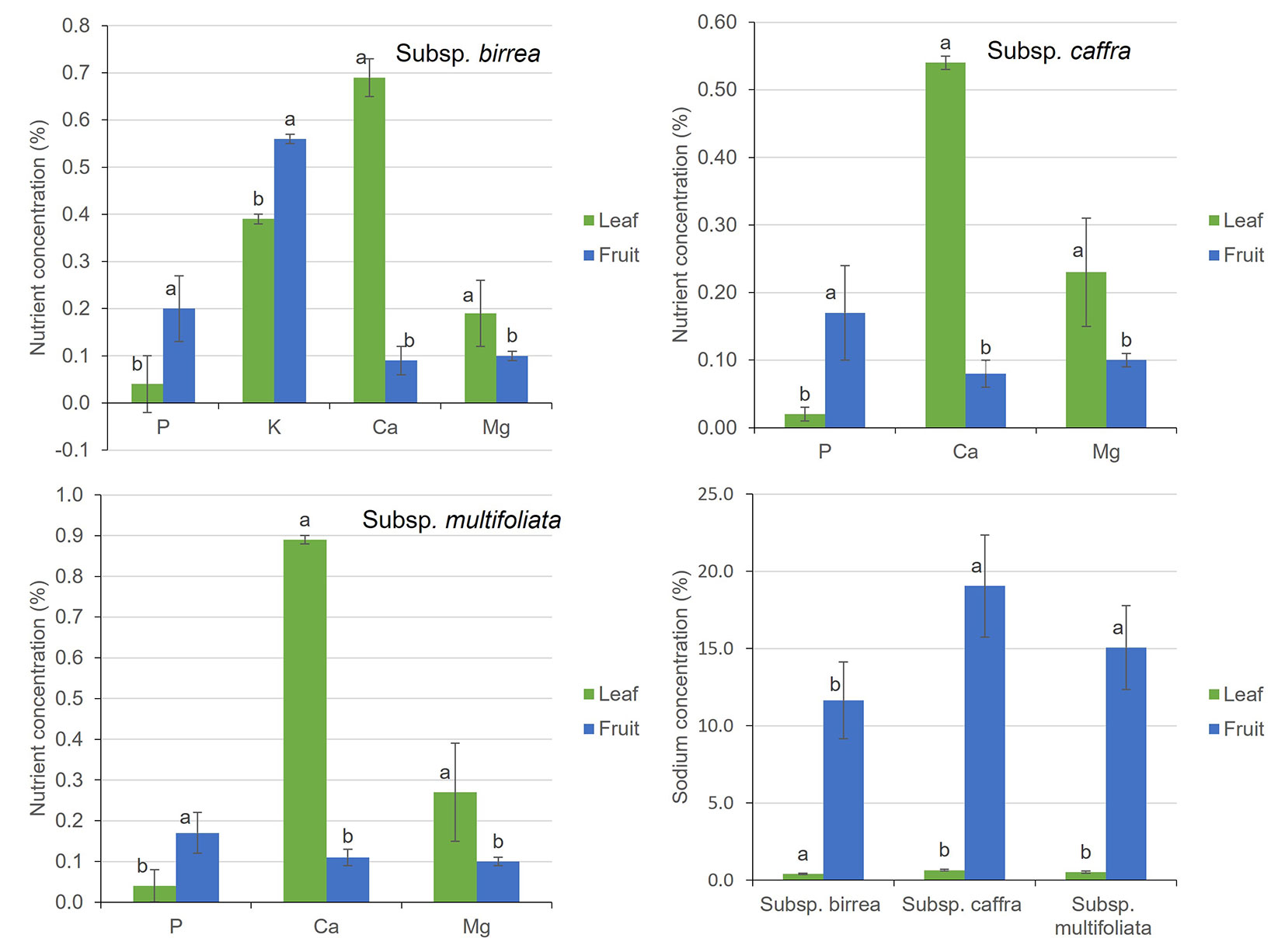

Fig. 2 - Mean concentration of macronutrients and sodium in the leaf and fruit litterfall of Sclerocarya birrea subspecies. Vertical bars show standard errors of the mean (n = 9). Bars within subspecies and nutrients with different letters are significantly different (α = 0.05).

Nutrient concentration in the leaf and fruit litterfall

Macro- and secondary nutrients

We found significant differences in P, Ca, Mg, and Na concentration between leaf and fruit littefall across all subspecies (Tab. 2). K concentration in leaf and fruit litterfall differed in subsp. birrea only (Tab. 2). Additionally, P was significantly higher in the fruit litterfall (0.17%-0.20%) than in leaf litterfall (0.02%-0.04%) for all subspecies (Fig. 2). In subsp. birrea, K was higher in fruit (0.56 ± 0.03%) than in leaves (0.39 ± 0.04%) (Fig. 2). Leaf and fruit S concentrations did not differ significantly across subspecies (Tab. 2). Concentration of Na also followed the same trend, with a higher concentration in fruit litterfall (11.65%-19%) than in leaf (0.41%-0.65%) for all subspecies (Fig. 2). Concentrations of Ca and Mg were higher in leaf litterfall, ranging from 0.54 ± 0.08% to 0.89 ± 0.12% Ca and 0.19 ± 0.01% to 0.27 ± 0.03% Mg, than in fruit litterfall, which ranged from 0.08 ± 0.01% to 0.11 ± 0.01% Ca and 0.10 ± 0.01% Mg (Fig. 2).

Tab. 2 - Summary of analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare macronutrients and sodium concentration in leaf and fruit litterfall of three Sclerocarya birrea subspecies in Tanzania. p-values from ANOVA are reported. (df): degree of freedom.

| Source of variation |

df | Subspecies | TN | P | K | S | Ca | Mg | Na |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litterfall type (leaf & fruit) |

1 | birrea | 0.0279 | <0.0001 | 0.0143 | 0.3129 | <0.0001 | 0.0007 | 0.0003 |

| 1 | caffra | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.4266 | 0.1944 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 1 | multifoliata | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.8421 | 0.3895 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

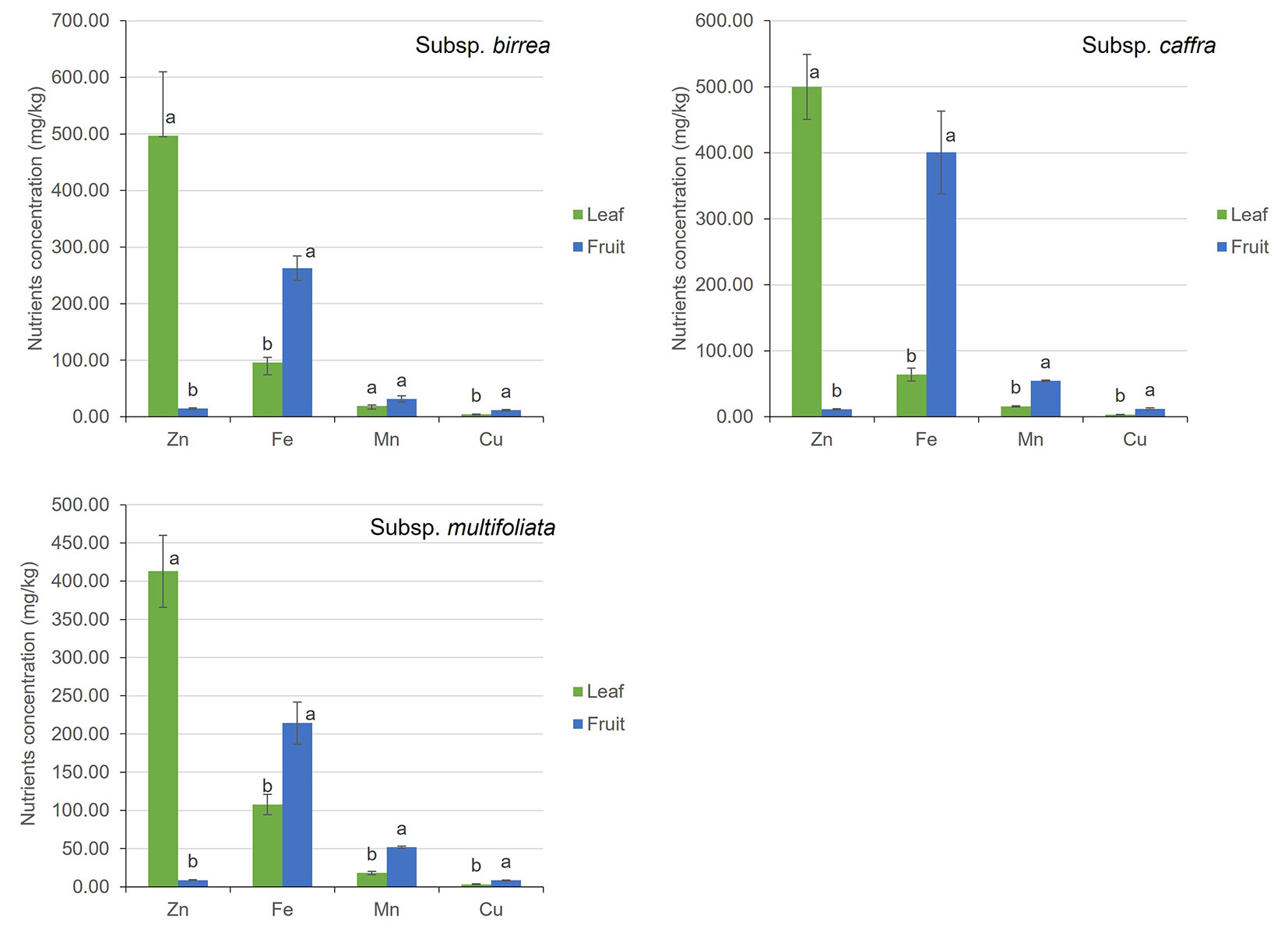

Micronutrients

Significant differences in Cu, Zn, Fe, and Mn concentration were recorded between leaf and fruit litterfall in all subspecies (Tab. 3). The concentrations of Cu, Fe and Mn were significantly higher in fruit (11.71 ± 1.05, 262.72 ± 21.67 and 31.42 ± 5.49 mg kg-1 for birrea, respectively; 12.32 ± 1.22, 400.59 ± 62.65 and 54.77 ± 0.93 mg kg-1 for caffra; and 8.35 ± 0.44, 214.13 ± 27.69 and 51.90 ± 1.36 mg kg-1 for multifoliata) than in leaf (4.39 ± 0.64, 95.87 ± 8.90 and 18.97 ± 2.18 mg kg-1 for birrea, respectively; 3.41 ± 0.39, 64.10 ± 9.90 and 16.08 ± 0.89 mg kg-1 for caffra; and 3.32 ± 0.54, 107.70 ± 13.28 and 18.04 ± 2.28 mg kg-1 for multifoliata) litterfall (Fig. 3). However, the concentration of Zn was 33 to 46 times higher in leaf (ranging from 412.97 ± 47.27 mg kg-1 in multifoliata to 499.78 ± 49.04 mg kg-1 in caffra) than in fruit litterfall (Fig. 3).

Tab. 3 - Summary of analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare micronutrient concentrations in the litterfall of three Sclerocarya birrea subspecies in Tanzania. p-values from ANOVA are reported. (df): degree of freedom.

| Source of variation |

df | Subspecies | Cu | Zn | Fe | Mn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litterfall type (leaf & fruit) |

1 | birrea | <0.0001 | 0.0006 | <0.0001 | 0.0515 |

| 1 | caffra | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 1 | multifoliata | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0032 | <0.0001 |

Fig. 3 - Mean concentration of micronutrients in the leaf and fruit litterfall of Sclerocarya birrea subspecies. Vertical bars show standard errors of the mean (n = 9). Bars within subspecies and nutrients with different letters significantly differ at α = 0.05.

Contribution of litterfall in enhancing soil fertility in drylands of Tanzania

We found that only the OC and K concentrations in soil under the tree canopy were significantly (p < 0.05) higher (0.77 ± 0.25% and 0.40 ± 0.15 cmolc kg-1) than in soil away from the canopy for subsp. birrea (0.46 ± 0.10% and 0.22 ± 0.07 cmolc kg-1, respectively - Tab. 4). However, the soil OC was low in all the soils (<2.5%) as per Landon ([21]). The soil pH, Cu, Zn, Mn, Fe, CEC, TN, Ca, Mg, Na, extractable P, and available S did not differ between soil under and away from the canopy of subsp. birrea (Tab. 4). For subsp. caffra, soil pH, Cu, Zn, Mn, Fe, CEC, TN, OC, Ca, Mg, Na, K, and extractable P did not significantly differ from those away from the canopies (Tab. 4).

Tab. 4 - Mean values (± standard error, n = 9) of selected soil properties under and away from the canopies of Sclerocarya birrea subspecies in Tanzania. (*): p < 0.05; (**): p < 0.01.

| Soil properties |

Subsp. birrea | Subsp. caffra | Subsp. multifoliata | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under canopy |

Away from canopy |

Pr > |t| | Under canopy |

Away from canopy |

Pr > |t| | Under canopy |

Away from canopy |

Pr > |t| | |

| pH (in H2O) | 6.37 ± 0.27 | 6.16 ± 0.28 | 0.1189 | 6.59 ± 0.25 | 6.57 ± 0.23 | 0.9014 | 6.65 ± 0.60 | 6.50 ± 0.65 | 0.6265 |

| Cu (mg kg-1) | 0.46 ± 0.20 | 0.44 ± 0.22 | 0.8279 | 0.95 ± 0.65 | 1.14 ± 0.61 | 0.5446 | 2.51 ± 3.66 | 0.95 ± 0.39 | 0.2375 |

| Zn (mg kg-1) | 0.92 ± 0.31 | 0.78 ± 0.49 | 0.5119 | 0.77 ± 0.28 | 0.99 ± 0.62 | 0.3626 | 0.47 ± 0.34 | 0.43 ± 0.37 | 0.8169 |

| Mn (mg kg-1) | 43.85 ± 7.76 | 39.94 ± 15.94 | 0.5178 | 36.35 ± 17.70 | 33.99 ± 13.11 | 0.7521 | 13.55 ± 4.10 | 13.52 ± 4.34 | 0.9882 |

| Fe (mg kg-1) | 40.49 ± 17.34 | 67.43 ± 44.20 | 0.1081 | 19.36 ± 11.31 | 22.10 ± 13.44 | 0.6459 | 17.88 ± 15.55 | 23.84 ± 21.91 | 0.5154 |

| S (mg kg-1) | 26.08 ± 32.76 | 15.21 ± 10.5 | 0.3573 | 1.70 ± 0.10 | 1.57 ± 0.08 | 0.0108* | 67.85 ± 18.13 | 91.51 ± 54.25 | 0.2436 |

| CEC (cmolc kg-1) | 5.07 ± 0.96 | 4.36 ± 0.36 | 0.0655 | 3.55 ± 0.34 | 3.77 ± 0.33 | 0.1855 | 3.75 ± 1.56 | 3.23 ± 1.47 | 0.4764 |

| TN (%) | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.05 | 0.1515 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.0616 | 0.08 ± 0.05 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.6296 |

| OC (%) | 0.77 ± 0.25 | 0.46 ± 0.10 | 0.0066** | 1.21 ± 0.25 | 1.04 ± 0.31 | 0.2155 | 0.86 ± 0.37 | 0.67 ± 0.33 | 0.2605 |

| Avail. P (mg kg-1) | 5.44 ± 4.20 | 6.67 ± 9.38 | 0.7244 | 9.70 ± 15.00 | 3.99 ± 3.23 | 0.2935 | 8.38 ± 5.45 | 8.19 ± 8.97 | 0.9572 |

| Ca (cmolc kg-1) | 2.89 ± 0.49 | 2.71 ± 0.38 | 0.3980 | 1.29 ± 0.33 | 1.19 ± 0.33 | 0.5455 | 1.57 ± 0.97 | 1.18 ± 0.63 | 0.3286 |

| Mg (cmolc kg-1) | 1.07 ± 0.73 | 0.75 ± 0.40 | 0.2825 | 1.57 ± 0.46 | 1.47 ± 0.46 | 0.6492 | 0.90 ± 0.45 | 0.89 ± 0.31 | 0.9668 |

| Na (cmolc kg-1) | 0.20 ± 0.08 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 0.1519 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.7408 | 0.29 ± 0.12 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.0472* |

| K (cmolc kg-1) | 0.40 ± 0.15 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 0.0068** | 1.02 ± 0.54 | 0.64 ± 0.38 | 0.1079 | 0.30 ± 0.13 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.0516 |

Available S was significantly (p<0.05) higher in the soils under canopies (1.70 ± 0.10 mg kg-1) than those away from the canopies (1.57 ± 0.08 mg kg-1) for subsp. caffra only (Tab. 4). The soil in Kiegea village, Morogoro municipal, where the subspecies caffra is found, had very low available S (< critical value of 9 mg S kg-1), but S was sufficient in Bonchugu village, Serengeti district, and Malinzanga village, Iringa district, where subspecies birrea and multifoliata, are found, respectively, as per Huda et al. ([17]) and Landon ([21]). For subsp. multifoliata, the concentration of Na in soils under the canopy was significantly (p<0.05) higher (0.29 ± 0.12 cmolc kg-1) than that away from the canopy (0.19 ± 0.06 cmolc kg-1 - Tab. 4). However, all soils had deficient soil exchangeable K (< 0.41 to 1.2 cmolc kg-1), except soils under the canopy of the subsp. caffra in Kiegea village as per Landon ([21]). There were no significant differences in soil pH, Cu, Zn, Mn, Fe, CEC, TN, OC, Ca, Mg, and P in soils under and away from the canopies of the subsp. multifoliata (p <0.05 - Tab. 4). Generally, all soils studied had low Zn (< 1.0 mg kg-1), low P (< 15 mg kg-1), and low exchangeable Ca (< 5.1 to 10.0 cmolc kg-1 - [21]).

Discussion

This study provides a quantitative assessment of the potential of the litterfall of Sclerocarya birrea subspecies to enhance soil fertility in agroforestry systems. Notable differences in leaf and fruit litterfall may be related to the roles of the respective nutrients in plant growth. Higher concentrations of Cu, Fe, Mn, P, and Na in fruit litterfall than in leaf litterfall of subspecies (Tab. 2, Fig. 2, Fig. 3) are due to the deposition of these nutrients in reproductive parts of the plants, i.e., fruit growth and seed development ([19]). These results also show that when fruits are harvested, Cu, Fe, Mn, and P may not be recycled in agroforestry systems and may need to be supplemented from other sources. Lack of significant difference in OC and S in leaf and fruit litterfall indicates that both leaf and fruit litter have comparable potential addition of OC and S in the soil. The results in Tab. 1show that litterfall can potentially supply about 411.6 and 495.7 kg OC from the accumulation of 1 ton of leaf and fruit, respectively.

The higher concentrations of Zn, TN, Ca, and Mg in leaf litterfall than in fruit litterfall across all subspecies are related to the significant role of these nutrients in leaf physiological functions in photosynthesis. Zinc plays a vital role in the catalytic reaction of the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, which occurs in chloroplasts and the cytoplasm, thereby enhancing photosynthesis and biomass production by increasing CO2 absorption per unit leaf area ([27]). Calcium and Mg are positively correlated to photosynthesis ([29]), which mostly occurs in leaves. Based on the N, P, and K concentration in Fig. 2, one ton of leaf litterfall can supply approximately 10 to 12 kg N, 0.2 to 0.4 kg P, and 3.9 to 6.4 kg K, while fruit litterfall can supply 5.7 to 9.4 kg N, 1.7 to 2.0 kg P, and 6.4 kg K. The amount of N, P, and K supplied through litterfall is lower than the recommended rates for crop production. Therefore, high levels of litterfall are needed to meet crop production macronutrient requirements. Leaf and fruit litter can supply substantial amounts of OC in the soil.

Soil fertility status under and away from the canopy reflects litterfall nutrient and OC concentrations. Significant higher soil exchangeable K and OC under the canopy of the subspecies birrea, S under the subspecies caffra, and Na under the subspecies multifoliata (Tab. 4), can be linked to the contribution of litterfall to enhance these aspects of soil fertility. The results are consistent with the highest OC, K, and S for specific subspecies. These findings are in line with the existing consensus that trees improve soil nutrient status and that agroforestry, in general, replenishes soil fertility ([14]). Soil Cu, Zn, Mn, S, CEC, TN, Ca, Mg, and Na were higher (though not significantly different) under the canopies of subsp. birrea as compared to that away from canopies. The significantly higher OC (0.77%) and K (0.40 cmolc kg-1) under the canopy than away from the canopy OC (0.46%) and K (0.22 cmolc kg-1) of subspecies birrea in Bonchungu, Serengeti (Tab. 4) may be linked to litter residue management. Similarly, soil OC was reported to be higher under the canopy of Prosopis juliflora and Acacia nilotica in rangeland and agroforestry systems ([42]). Another study reported higher soil K concentrations under the canopies of Acacia albida and Kigelia africana than away from the canopies ([11]).

Generally, the soil pH and concentration of Mn, S, TN, OC, Ca, Mg, and K were higher (by 0.3%, 7%, 8%, 22%, 14%, 59%, 8%, and 37%, respectively) under the canopies of subsp. caffra than away from them, and this is probably due to litterfall accumulation. On the contrary, higher Zn, Mn, Fe, Na (by 20%, 29%, 14%, 6%, and 8%, respectively) in soils away from the canopies of this subspecies than in soils under the canopies indicates the possibility of greater absorption of these nutrients by trees than replenishment through litterfall. Only soil S concentration under the canopies of subsp. caffra differed significantly from that outside the canopies (Tab. 4), consistent with Pérez-Suárez et al. ([40]). The higher S under the canopy (1.70 mg kg-1) than away from the canopy (1.57 mg kg-1) can be linked to the addition of S from litterfall in highly S-deficient soil.

For S. birrea subsp. multifoliata, the soil pH, Cu, Zn, Mn, CEC, OC, P, Ca, Mg, Na, and K were 2%, 62%, 9%, 0.2%, 14%, 22%, 2%, 25, 1%, 35% and 37% higher under the canopies compared to those away from canopies. However, the concentration of soil Fe, S, and TN was 33%, 35%, and 12% higher in soils away from tree canopies than that under the canopies. Na was the only soil nutrient that significantly differed from that away from the canopies (Tab. 4). Similarly, Comole et al. ([8]) reported higher soil Na under the canopy of Prosopis velutina than that away from the canopies.

Soils under the canopies of all Sclerocarya birrea subspecies had higher OC, Mn, K, Ca, and Mg concentrations than those in open fields (Tab. 4). This could be due to the increased litterfall from trees and a higher biological activity, including litterfall decomposition ([2]). Differences in nutrient concentration under the canopies among the subspecies can be related to differences in the soils where the subspecies studied were found. Higher nutrient concentrations under tree canopies may also be attributed to factors such as high concentrations of bird droppings, animal excrement, and urine, which can contribute to high soil nutrient concentrations over time ([50]). This is because trees in drylands are often scattered, and provide shelter and food for birds and animals. The breakdown and mineralization of plant residues probably contributed to higher carbon and nutrient contents in the soils under the canopies of all S. birrea subspecies.

Sclerocarya birrea is a dryland tree species that inhabits soils with low fertility and receives little rainfall ([15]). Additionally, the subsp. multifoliata is more dominant in drier areas, followed by the subspecies birrea and caffra ([15], [33], [34]). Plants adapted to dry and infertile soil exhibit slow growth rates, long leaf longevity, low nutrient concentrations, and high concentrations of secondary chemical compounds such as lignin, which tend to immobilize nutrients in green tissues and increase the C:N ratio, thereby affecting nutrient cycling ([9]). As a result, plants at nutrient-limited sites produce small amounts of low-quality litterfall, which decomposes slowly and adds limited nutrients to the soils ([51]). Additionally, the leaves and fruits of S. birrea subspecies are used as fodder by both wild and domestic animals ([15]), which may be attributed to slight differences in nutrient concentrations in soils under and away from the canopies.

The leaf and fruit litterfall of S. birrea subspecies had high C:N ratios (Tab. 1), which suggests that organic carbon and nutrients are immobilized at initial stages of decomposition and will slowly be released to become available for use by crops. However, fruit and leaf litterfall of the subsp. birrea had high TN and lower C:N ratios compared to subspecies multifoliata and caffra (Tab. 1). The low C:N ratio of S. birrea subsp. birrea compared to that of subspecies caffra and multifoliata, suggests that the litterfall of the subspecies birrea can decompose in a short time and release nutrients into the soil for crop uptake ([24], [49]). Litterfall N is the primary nutrient that determines the decomposition of litterfall during the early stages of the litterfall decomposition process. In contrast, lignin is the major litterfall component that influences its decomposition at later stages ([25]). This suggests that S. birrea subspecies are among the dryland trees with the potential to improve soil fertility and boost agricultural productivity in drylands if adopted for agroforestry and their litterfall is used to amend soil fertility. However, more information is needed on their potential effects on dryland crops before promoting and adopting them in agroforestry.

Enhancing C storage in drylands with high C:N ratio litterfall through agroforestry is critical for increasing C sequestration in agricultural soils with relatively low soil vegetation cover. Our results show that the C:N ratios are higher in S. birrea subspecies fruit than leaf litterfall (Tab. 1). The findings of this study concur with McGroddy et al. ([28]) and Dent et al. ([9]), who reported that the C:N ratios in forest litterfall range from 35:1 to 88:1. Microbial decomposers such as bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes, which have lower C:N ratios than most litterfall types, mainly decompose litterfall ([24]). In general, the ideal litter C:N ratio for microbial activity is 20-30 ([24]). Mineralization is expected when the litter C:N ratio is less than 20:1 during litter decomposition, and immobilization is likely when the ratio exceeds 30:1 ([24]). Therefore, higher C:N ratios in the litterfall of all S. birrea subspecies imply that most nutrients are immobilized and decomposition is slow, allowing them to store carbon in their biomass for long time. The degree of C storage may vary among S. birrea subspecies due to slight differences in C:N ratio, as subspecies birrea had a relatively low C:N ratio, but still fall within C:N >1:30 (Tab. 1). Thus, S. birrea subspecies are potential candidate trees for use in drylands restoration to counteract global warming through carbon storage in drylands.

Early stages of plants’ litterfall decomposition are often governed by the availability of limiting elements, such as litter N and C:N ratios, and late stages of litterfall decomposition have been linked to the elements needed to decompose recalcitrant secondary compounds, such as lignin, that accumulate in the remaining litterfall ([3]). The other main predictors of litterfall decomposition rate, in addition to N and C:N ratios, are P and C:P, lignin and lignin/N, and cellulose ([20]). Thus, there is a need for further research to explore litterfall production and its decomposition rate. Moreover, further studies are needed to determine secondary chemical compounds in leaf and fruit litterfall and in other litterfall types, such as twigs and branches, as well as to improve our understanding of litterfall decomposition rate for Sclerocarya birrea subspecies, releasing nutrients for crop use and storing C. Twigs and branches of trees/plants normally contain proportionally higher lignin concentrations hence, higher lignin/N ratios than leaves and fruits ([49]). Thus, the high C:N ratios in the leaf and fruit litterfall of S. birrea subspecies (C:N > 30) suggest that these trees can immobilize carbon for a considerable period, making them suitable for mitigating global warming by storing carbon in their biomass. Furthermore, research to study total carbon stored in the biomass of the Sclerocarya birrea subspecies is recommended to better understand their contribution and potential to combat global warming.

Conclusions

The leaf and fruit litterfall of the Sclerocarya birrea subspecies has the potential to improve soil fertility and store carbon in dryland soils, though their potential varies across subspecies. The fruit litterfall generally had higher organic carbon and nutrient concentrations than leaf litterfall. As the fruits have economic potential, it will be necessary to supplement nutrients and apply organic carbon amendments. Soil pH and CEC under the canopy of Sclerocarya birrea subspecies and in open fields were generally similar, both being slightly acidic and exhibiting very low CEC values. Soils under the canopies were generally enriched with most nutrients compared to those in open fields, except for Fe.

Leaf and fruit litterfall of Sclerocarya birrea subspecies has the potential to enhance soil fertility but requires supplementation with other nutrient sources, as it showed high C:N ratio. This suggests that litterfall cannot be easily decomposed and mineralized, and that nutrients are immobilized and not readily available for crop uptake due to slow decomposition. From a climate change mitigation perspective, higher C:N ratios imply that Sclerocarya birrea subspecies can store carbon in their biomass for a long time, thus are potential tree species for combating global warming.

Author’s Contributions

Munna AH: conceived the study, methodology, data curation and analysis, interpretation of results, writing the first draft, reviewing and editing of the manuscript, and project administration; Amuri NA: methodology, software, data curation and analysis, validation, and interpretation of results; reviewing and editing of the manuscript; Hieronimo P: reviewing and editing of the manuscript and Woiso DA: reviewing and editing of the manuscript. All authors endorsed the publication of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mr. Joseph Mwita Chacha, Mr. Richard Msigala, and Mr. Yohana of Bonchugu village, Malinzanga, and Kiegea village in Serengeti district, Iringa district, and Morogoro municipality, respectively, and Mr. Ernest William Dyanka for their support during field data collection. Also, we thank Mr. Yahya Abeid for assisting in the identification of subspecies during field surveys. This study received no external funding.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Supplementary Material

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Nyambilila A Amuri 0000-0003-3092-3458

Department of Soil and Geological Sciences, Sokoine University of Agriculture, P.O. Box 3008, Chuo Kikuu, Morogoro (Tanzania)

Department of Biosciences, Sokoine University of Agriculture, P.O. Box 3038, Chuo Kikuu, Morogoro (Tanzania)

Department of Agricultural Engineering, Sokoine University of Agriculture, P.O. Box 3003, Chuo Kikuu, Morogoro (Tanzania)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Munna AH, Amuri NA, Woiso DA, Hieronimo P (2025). The potential of the marula tree, Sclerocarya birrea, (A. Rich.) Horchst subspecies litterfall in enhancing soil fertility and carbon storage in drylands. iForest 18: 366-374. - doi: 10.3832/ifor4478-018

Academic Editor

Emilia Allevato

Paper history

Received: Sep 28, 2023

Accepted: Jun 05, 2025

First online: Dec 07, 2025

Publication Date: Dec 31, 2025

Publication Time: 6.17 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2025

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 885

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 213

Abstract Page Views: 361

PDF Downloads: 276

Citation/Reference Downloads: 1

XML Downloads: 34

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 57

Overall contacts: 885

Avg. contacts per week: 108.68

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

(No citations were found up to date. Please come back later)

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Assessing food sustainable intensification potential of agroforestry using a carbon balance method

vol. 12, pp. 85-91 (online: 24 January 2019)

Research Articles

Assessing the relative role of climate on litterfall in Mediterranean cork oak forests

vol. 11, pp. 786-793 (online: 14 December 2018)

Research Articles

Future land use and food security scenarios for the Guyuan district of remote western China

vol. 7, pp. 372-384 (online: 19 May 2014)

Research Articles

Soil C:N stoichiometry controls carbon sink partitioning between above-ground tree biomass and soil organic matter in high fertility forests

vol. 8, pp. 195-206 (online: 26 August 2014)

Editorials

Change is in the air: future challenges for applied forest research

vol. 2, pp. 56-58 (online: 18 March 2009)

Research Articles

Effects of tree species, stand age and land-use change on soil carbon and nitrogen stock rates in northwestern Turkey

vol. 9, pp. 165-170 (online: 18 June 2015)

Research Articles

Potential relationships of selected abiotic variables, chemical elements and stand characteristics with soil organic carbon in spruce and beech stands

vol. 14, pp. 320-328 (online: 09 July 2021)

Research Articles

Roadside vegetation: estimation and potential for carbon sequestration

vol. 3, pp. 124-129 (online: 27 September 2010)

Research Articles

Dynamics of soil organic carbon (SOC) content in stands of Norway spruce (Picea abies) in central Europe

vol. 11, pp. 734-742 (online: 06 November 2018)

Research Articles

Forest management with carbon scenarios in the central region of Mexico

vol. 14, pp. 413-420 (online: 15 September 2021)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword