Combined effects of short-day treatment and fall fertilization on growth, nutrient status, and spring bud break of Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 10, Issue 1, Pages 242-249 (2017)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor2178-009

Published: Feb 11, 2017 - Copyright © 2017 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Although effects of short-day treatment and fall fertilization on seedling development have been studied independently, their combined influences are not well elucidated. We explored growth, nutrient concentration, and spring bud break of Chinese pine (Pinus tabulaeformis Carr.) seedlings exposed to two photoperiod treatments (short-day consisting of 3 weeks of 18-hr nights in late summer and ambient day length) and three rates of fall N fertilization (0, 12 and 24 mg N per seedling). Seedlings were assessed before fall fertilization and at the end of the growing season. Bud break timing was evaluated the following spring. Increased foliar P concentration concurrent with reduced root P and K concentration occurred in short-day treated seedlings at the conclusion of photoperiod treatment. By the end of the growing season, short-day treatment resulted in greater N and P concentration in the stems, and P concentration in the foliage. It also induced smaller foliage and stem dry mass in both stages. Fall fertilization consistently enhanced tissue N concentration, but interaction effects with short-day treatment were generally non-significant. Short-day treatment curtailed shoot growth, induced terminal bud set, and hastened spring bud break (by only one day) for this mid-latitude seed source (41° N). Thus, short-day treatment or fall fertilization each promoted an increased nutrient concentration, while having only a minor effect on spring bud break.

Keywords

Photoperiod, Autumn Fertilization, Nutrient Loading, Bud Break

Introduction

Artificial shortening of photoperiod by short-day treatment in late summer is a common practice in forest nurseries to promote growth cessation and increase cold hardiness ([23]). During the naturally long days of summer at high latitudes, where termination of photoperiodic lighting may not be sufficient to trigger terminal bud set and initiate the hardening phase, short-day treatment has been a routine nursery procedure for years ([23]). Moreover, the popularity of short-day treatment is associated with late-summer and early-autumn planting at these higher latitudes, where seedlings are shipped for planting to facilitate new root development in the warm summer soil ([12]). During this period, seedlings may be in a state of quiescence (vs. rest) and are vulnerable to injury from lifting, transport, and planting ([28]). Thus, short-day treatment prior to late summer- and early autumn-planting is encouraged to promote seedling dormancy and facilitate handling ([28], [24]).

When actively growing seedlings are exposed to short-day treatment, they gradually undergo a transition to bud set, frost and drought hardening, and the dormancy phase ([23]). Cessation of shoot growth, reduced plant dry mass and a subsequent shift in allocation to root production have been observed in short-day treated seedlings ([3], [5], [10]). This stoppage of growth due to short-day treatment provides the opportunity to enrich seedling nutrient concentration ([39]). Nutrient status is a crucial determinant of seedling quality and is consequently monitored to evaluate nursery practices ([34] and references therein). To the best of our knowledge, short-day studies have predominantly dealt with frost hardiness, seedling size, root growth potential, needle primordia, and sugar concentration ([11], [28], [29], [38], [31]). Therefore, simultaneously studying seedling nutrient status could help to improve our understand of how short-day treatment affects seedling quality.

Fall fertilization, also referred to as autumn or late-season fertilization, can promote accumulation of nutrient reserves in seedlings ([41]) and has long been considered a beneficial nursery cultural practice ([43], [44]). The effect of fall fertilization on seedling functional attributes, especially nutrient reserves, is dependent on nitrogen (N) source ([41]), rate ([15], [1]), timing ([33]), application method ([4]), and nutrient status prior to fall fertilization ([27]). If short-day treated seedlings were kept in the nursery and fertilized during fall instead of being shipped to the field for summer planting, than this may further alter their morphological and physiological attributes. So far the combined effects of short-day treatment and fall fertilization on seedling quality remain unknown despite the adoption of both these treatments in many nurseries ([4], [30], [49]).

The speed of spring bud break is considered an indicator of seedling dormancy and vigor ([25]). Late-spring frosts that coincide with the sensitive phases of spring bud break may cause damage and therefore spring bud break has been studied intensively ([23]). However, it is unknown whether short-day treatment and fall fertilization combined accelerate spring bud break, although they have been proven to do so individually ([2], [9]).

Relative to consistent use at high latitudes (> 45° N), short-day treatment is sometimes implemented by growers in mid-latitudes ([23]), where night length is relatively long and does not vary as much between summer and winter ([20]). However, studies conducted in mid-latitudes (30°-45° N) have proven that short-day treatments effectively altered seedling size and root growth capacity of transplants ([16], [20]). These findings indicate that short-day cultural practices can also manipulate the quality of mid-latitude tree species.

Chinese pine (Pinus tabulaeformis Carr.) is a mid-latitude evergreen coniferous species and is the most widely distributed conifer in northern China (31° 00′ - 43° 33′ N, 103° 20′ - 124° 45′ E), with a range of average temperature from -19 to 5 °C in January and from 13 to 25 °C in July ([46]). Studies show that Chinese pine can be vulnerable to spring frost damage during bud break ([47], [48]). This implies that early spring bud break could increase this risk, and it is important to assess the impact of nursery practice on spring bud break. In the present paper, Chinese pine container seedlings were exposed to short-day treatment and then supplemental fertilization during hardening. We aimed to: (1) examine whether there would be differences in nutrient status between natural day and short-day treated seedlings at the termination of photoperiod treatment; (2) explore the effect of combined short-day treatment and fall fertilization on seedling size and nutrient status at the end of the growing season; (3) investigate whether combining short-day treatment and fall fertilization would accelerate spring bud break.

Materials and methods

Seedling material

On 15 April 2013 (week 1), seeds from a regional seed orchard (National Seed Orchard for Chinese Pine, Qigou Forest Farm, 41° 00′ N and 118° 27′ E, 526 m a.s.l.) were sown into hard plastic cells (SC10 Super, cell volume 164 ml, cell depth 21 cm - Ray Leach “Cone-tainers”TM, Stuewe & Sons, Inc., Oregon, USA) filled with a 3:1 (v:v) mix of peat:perlite medium. Ninety-eight cells were incorporated into a tray (Ray Leach “Cone-tainers”TM RL98, Ray Leach “Cone-tainers”TM, Stuewe & Sons, Inc., Oregon, USA - 30 trays and 2940 seedlings in total). The trays were then placed on raised benches of a polyethylene-covered, ventilated greenhouse under natural photoperiod greenhouse at the Chinese Academy of Forestry Sciences in Beijing (40° 40′ N, 116° 14′ E). From 29 April to 15 July (weeks 3-14), each seedling was fertilized weekly, resulting in a total of 12 applications. N was supplied as NH4NO3 (Shanghai Research Institute of Chemical Industry); phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) were supplied as KH2PO4 (Guangdong Guanghua Sci-Tech Co., Ltd. China); and chelated micronutrients as disodium ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA, Xilong Chemical Co., China) and diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA, Jinke Fine Chemical Institute, Tianjin). Accumulated supplementary fertilizers were 80 mg N, 26 mg P, 33 mg K, 3 mg EDTA, and 0.9 mg DTPA seedling-1. P, K, EDTA and DTPA were evenly split into 12 equal amounts and applied weekly. N was delivered following exponential functions ([13] as modified by [40]) according to eqn. 1:

where r (0.357) was the relative addition rate required to increase Ns (initial N content in seed) to final N content (NT + NS), and NT (80 mg) was the desired amount to be added over the number of fertilizer applications (t = 12). Ns was determined to be 1.12 mg seed-1 from five replicates each comprising 15 seeds at sowing. The quantity of N to be applied on a specific week (Nt) between 29 April and 15 July was calculated using eqn. 2:

where Nt-1 is the cumulative amount of N added up to and including the previous application.

Each week the desired amounts of N, in addition to P, K, EDTA, and DTPA, were dissolved in water to ensure that 20 ml of solution, applied manually to each seedling, delivered the target amount of nutrients. Seedlings were rinsed after each application to avoid foliar fertilizer burn. Seedlings were watered to field capacity, approximately twice each week (State Forestry Administration 2013). From sowing (15 April) to the conclusion of fertilization (15 July), ambient temperature in the greenhouse averaged 25/18 °C (day/night) as measured at 15-min intervals with a JL-18 Series thermometer (Huayan Instrument and Equipment Co., Shanghai, China). Natural night length in the greenhouse was 10 h 42 min on 15 April and 9 h 17 min on 15 July, calculated from geometric sunset to geometric sunrise.

Photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization

Short-day treatment was initiated on 22 July (week 15), when seedling height and root collar diameter (RCD) were 9.4 ± 0.28 cm and 1.80 ± 0.04 mm, respectively (means ± SE, n = 50). Half of the actively growing seedlings (15 trays, 1470 seedlings) were covered under a blackout frame made of iron tubes, in which short-day treatment was provided by extending the night length to 18 h (from 2 pm to 8 am, reported for mid-latitude tree species - [20]) using a blackout curtain. On 11 August (week 17), the frame was removed after seedlings had received the 3-week short-day treatment. The remaining seedlings (15 trays, 1470 seedlings) continued to be exposed to natural day length. During the 3-week treatment period, all seedlings were irrigated as above, with fertilizer withheld to hasten bud set. For the natural day treated seedlings, bud set (the formation of bud scales at the apical shoot meristem) began on 28 July, with all seedlings not achieving bud set until 31 August. All the short-day treated seedlings had set terminal buds on 8 August (18 days from the initiation of short-day treatment). Fifteen trays from each photoperiod treatment were randomly allocated to the three fall fertilization treatments of 0, 12 and 24 mg N per seedling (henceforth referred to as 0F, 12F, and 24F) between 2 September and 7 October (weeks 21-26). The 30 trays were arranged in a completely randomized design with five trays each of six combinations of 2 photoperiod treatment × 3 fall fertilization in a complete 2 × 3 factorial design. Except for N, each seedling received the same amounts of P, K and chelated micronutrients, evenly split, for a total of six applications between 2 September and 7 October. Cumulative supplementary P, K, EDTA and DTPA were 13, 16.5, 1.5 and 0.45 mg, respectively.

At the conclusion of fall fertilization, seedlings were moved outdoors from the greenhouse to hasten hardening. On 22 November, seedlings were placed under white plastic sheeting and stored outdoor for the winter. Environmental parameters during various phases of seedling culture are shown in Tab. 1.

Tab. 1 - Environmental parameters in the greenhouse for the culture of Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings.

| Date | Weeks after sowing |

Nursery practice |

Natural night length |

Ambient temperature (°C, day/night) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 22-Aug 11 | 15-17 | SD treatment | 9 h 45 min | 27/24 |

| Aug 12-Sep 1 | 18-20 | - | 10 h 31 min | 25/22 |

| Sep 2-Oct 7 | 21-26 | Fall fertilization | 11 h 42 min | 23/19 |

| Oct 7-Nov 24 | 26-32 | Outdoor storage | 13 h 26 min | 8/6 |

Measurements

Prior to fall fertilization (1 September; week 20), five seedlings were randomly sampled from each tray (75 seedlings per photoperiod treatment; 150 seedlings in total) to evaluate growth response to photoperiod. After roots were gently washed free of growing medium, seedlings were measured for height and RCD. Seedlings were then separated into needles, stems, and roots and oven-dried at 65 °C for 48 h to determine dry mass. Then, within each tray, each tissue fraction of the five seedlings was subsequently combined to a composite sample, ground, sieved through a 0.25 mm screen, and wet-digested using the H2SO4-H2O2 method. A standard Kjeldahl digestion with water distillation was used to measure total N by a distillation unit (UDK-152®, VelpScientifica, USA). Phosphorus concentration was determined with a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Agilent 8453®, Germany) and K concentration was determined with atomic emission spectrophotometry (VARIN AA 220®, Elemental Spectroscopy, USA).

On 18 November (week 32), five seedlings from each tray (each photoperiod/fertilization combination replicate) were measured for height, RCD, dry mass, and the concentration of total N, P, and K. Nutrient uptake and morphological growth were defined as the difference observed prior to fall fertilization and after fall fertilization (at the end of the growing season). For morphological attributes, mean values from the same tray were used despite individual seedling being measured.

Bud break test

On 8 March 2014, six seedlings from each photoperiod/fertilization combination and replication (180 seedlings in total) were transplanted into sand-filled plastic pots (2.6 L, 30 cm depth) in the greenhouse under natural photoperiod. Heating resulted in ambient temperatures averaging 22/20°C (day/night). Soil moisture was kept optimal by irrigating pots with tap water every second day.

Spring bud break was assessed daily. Based on nine categories defined in the study on Picea abies (L.) Karst. seedlings ([8]), bud status of Chinese pine seedlings was divided into four categories: 1 = dormant buds; 2 = buds swollen, bud scales still covering the new needles; 3 = bud scales diverging, no elongation of needles; 4 = needles elongating and spreading. Chinese pine seedlings that reached stage 3 were defined as having broken bud. To calculate the number of days to spring bud break, logistic regressions were developed to predict the proportion of seedlings that had reached spring bud break with number of forcing days as the independent variable. Separate regressions were estimated for each combination of photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization based on trays (replicates), and days to 50% and 95% spring bud break were obtained by interpolation.

Statistical analysis

We performed two statistical analyses using SPSS® ver. 16.0 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Prior to fall fertilization (1 September), a t-test was used to evaluate effects of photoperiod treatment on morphological and nutritional attributes. A two-way ANOVA was used to analyze effects of photoperiod treatment, fall fertilization, and their interactions on morphological growth and nutrient uptake prior to fall fertilization through the end of the growing season (from 1 September to 18 November), nutrient concentration at the end of growing season (18 November), and the mean number of days to 50 % and 95 % spring bud break for a 2 × 3 factorial, completely randomized design. Separation of means for morphological and nutritional responses were ranked according to Duncan’s test at α = 0.05. The “Explore” function of SPSS was used to examine data prior to the t-test and ANOVA to ensure normality and variance homogeneity requirements and no transformations were necessary. Nutrient concentration and frequencies in spring bud break were arc-sine transformed to normalize data.

Results

Morphological and nutritional attributes after photoperiod treatment

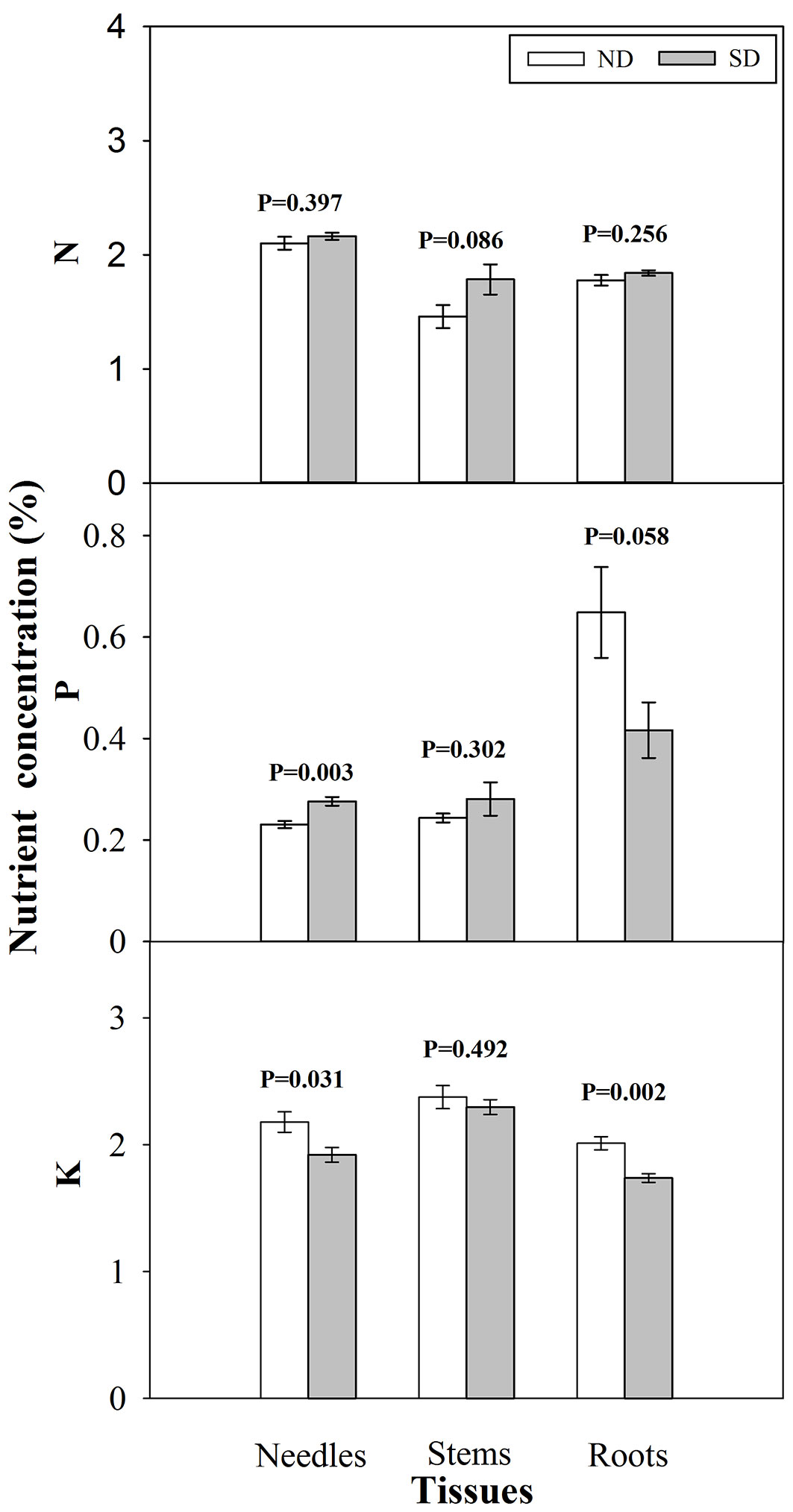

Seedlings exposed to short-day treatment showed significant reductions in height, RCD, and dry mass of needles and stems at the end of photoperiod treatment compared with those grown under natural day length (Tab. 2). There was no significant difference, however, in root dry mass between short-day and natural day treated seedlings, resulting in an increased root/ shoot ratio for short-day treated seedlings (Tab. 2). Short-day treatment enhanced P concentration in needles (Fig. 1) and a significant decline in K concentration in needles and roots.

Tab. 2 - Morphological characteristics (mean ± SE, n=75) and t-test P values of Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings under photoperiod manipulation (PT) of natural day length (ND) and short-day treatment (SD) after photoperiod treatment.

| PT | Height (cm) |

RCD (mm) |

Dry mass (g) | Root/Shoot | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needles | Stems | Roots | ||||

| ND | 12.6 ± 0.8 | 1.96 ± 0.06 | 0.421 ± 0.034 | 0.124 ± 0.011 | 0.113 ± 0.011 | 0.21 ± 0.01 |

| SD | 10.1 ± 0.5 | 1.79 ± 0.05 | 0.315 ± 0.023 | 0.0904 ± 0.008 | 0.0966 ± 0.008 | 0.24 ± 0.01 |

| P value | 0.007 | 0.027 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.216 | 0.025 |

Fig. 1 - Nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) concentration (mean ± SE, n=15) in tissues of Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings under photoperiod treatment (PT) of natural day length (ND) and short-day treatment (SD) after photoperiod treatment. P values are from a t-test with α = 0.05.

Morphological and nutritional changes during hardening

The interaction of photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization did not significantly affect growth increments in height (p = 0.813), RCD (p = 0.498), and tissue dry mass (p = 0.078-0.767) from the initiation of fall fertilization to the end of the growing season. For main effects, both photoperiod treatment (p = 0.002) and fall fertilization (p = 0.020) led to significant differences in height growth increment. Height growth increments in natural day and short-day treatment were 0.1 and 0.9 cm, respectively, during the period. Height growth increments were 0.2, 0.3, and 1.0 cm for 0F, 12F, and 24F, respectively. Height growth increment of 24F was greater than 0F and 12F, although there was no difference between 0F and 12F. Average RCD growth increment was 0.62 mm and did not differ by photoperiod treatment or fall fertilization (p = 0.125-0.980). Accumulated dry mass in needles, stems, and roots were 0.173, 0.106, and 0.341 g, respectively; and dry mass of these tissues increased during hardening by 47 %, 99 %, and 325 %, respectively, though these parameters were not influenced by photoperiod treatment or fall fertilization.

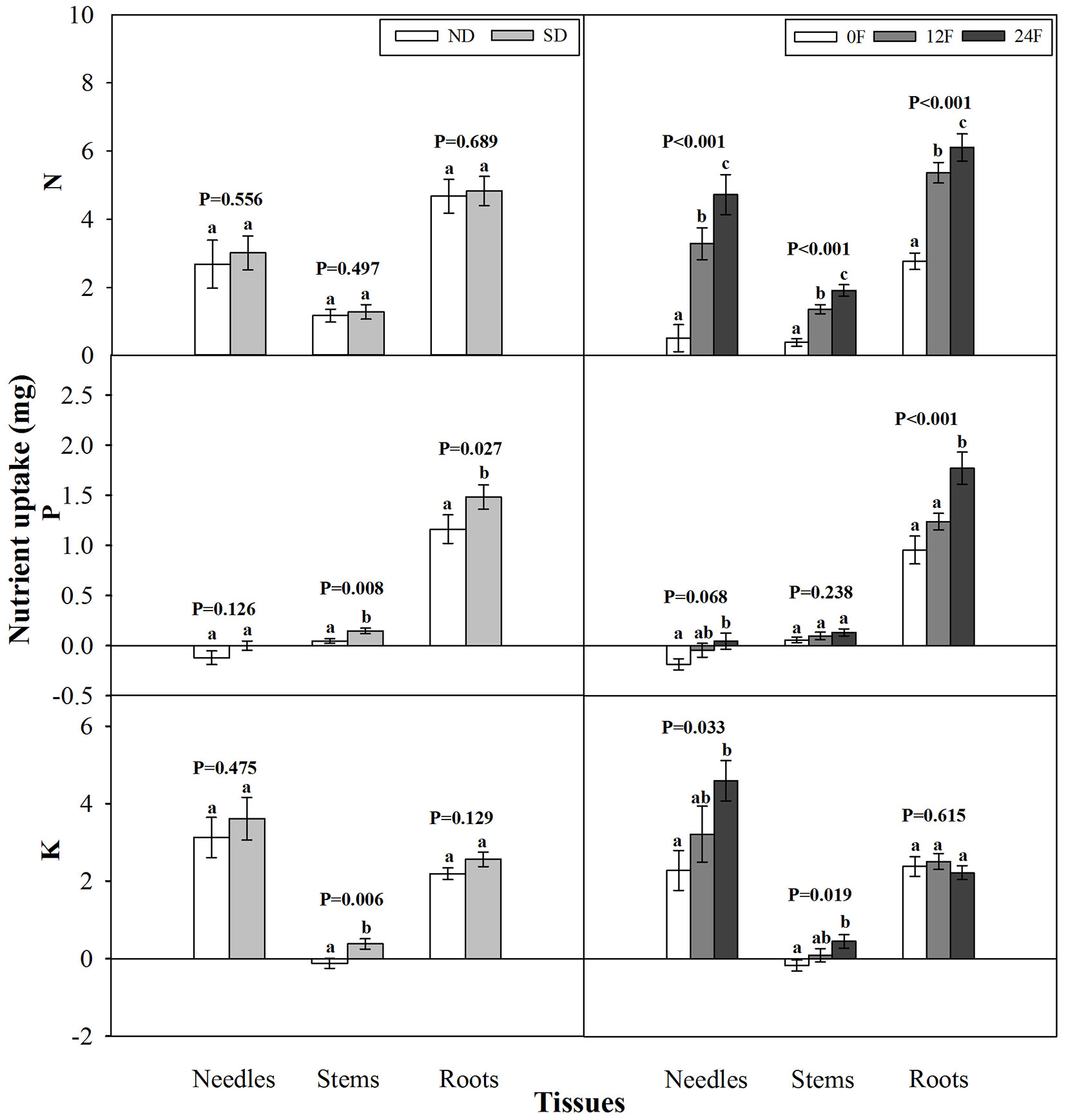

Photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization did not interact significantly to affect tissue nutrient uptake from the initiation of fall fertilization to the end of the growing season (p = 0.147-0.704). Short-day treatment did not enhance N uptake in any tissues compared with the natural day length but did significantly increase P uptake in stems and roots, as well as stem K uptake (Fig. 2). Tissue N uptake consistently increased with increasing fall-applied N rates. Although all seedlings received the same amounts of P and K fertilizers during fall, seedlings with fall-applied N exhibited increased uptake in P and K compared to those without fall-applied N, particularly for P in needles and roots, and K in needles and stems.

Fig. 2 - Nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) content (mean ± SE) increments prior to fall fertilization through the end of the growing season in tissues of Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings treated by photoperiod treatment (ND: natural day length; SD: short-day; n=15; left) and nursery fall fertilization (0F, 12F, 24F: 0, 12, and 24 mg N/seedlings, respectively; n=10; right). Different letters above the bars within tissues indicate statistically significant differences according to Duncan’s test at the 5% level. P values from the ANOVA for main effects of photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization were provided due to lack of significant interactions.

Morphological and nutritional attributes at the end of the growing season

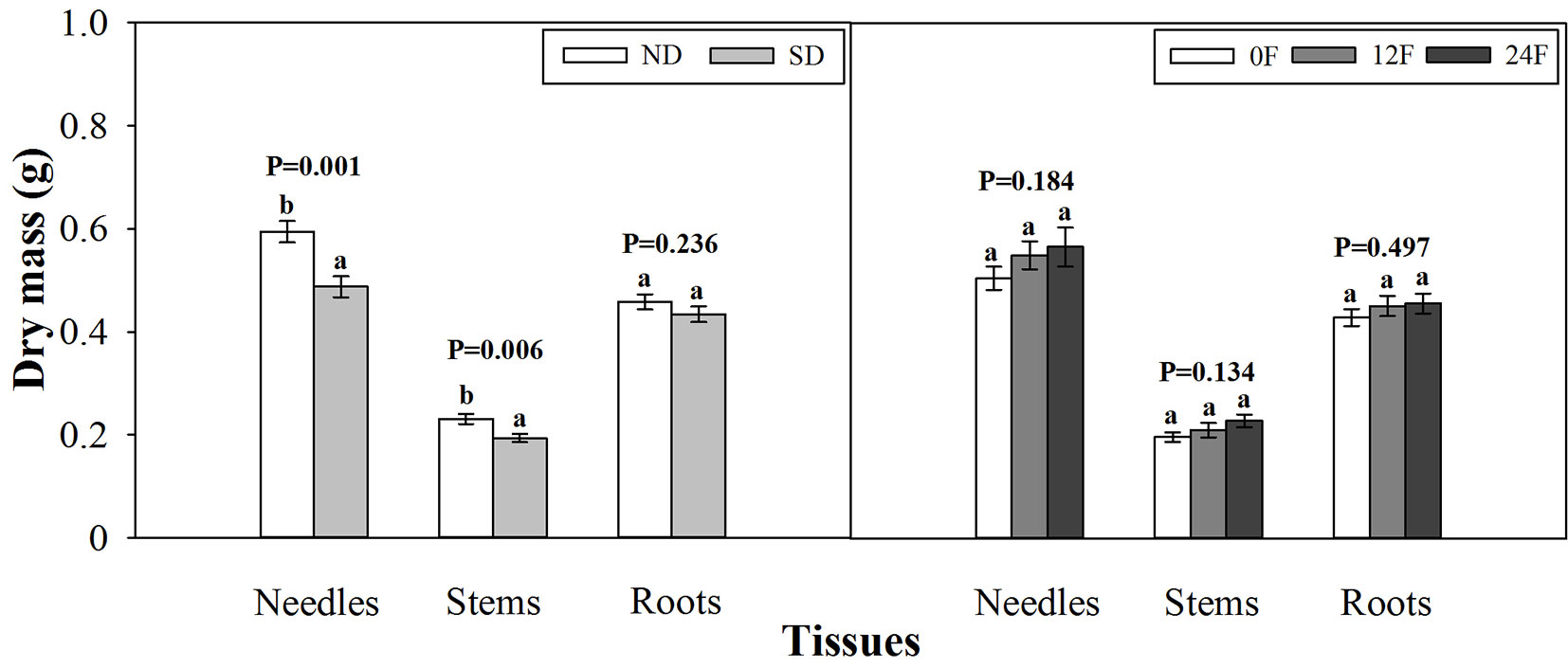

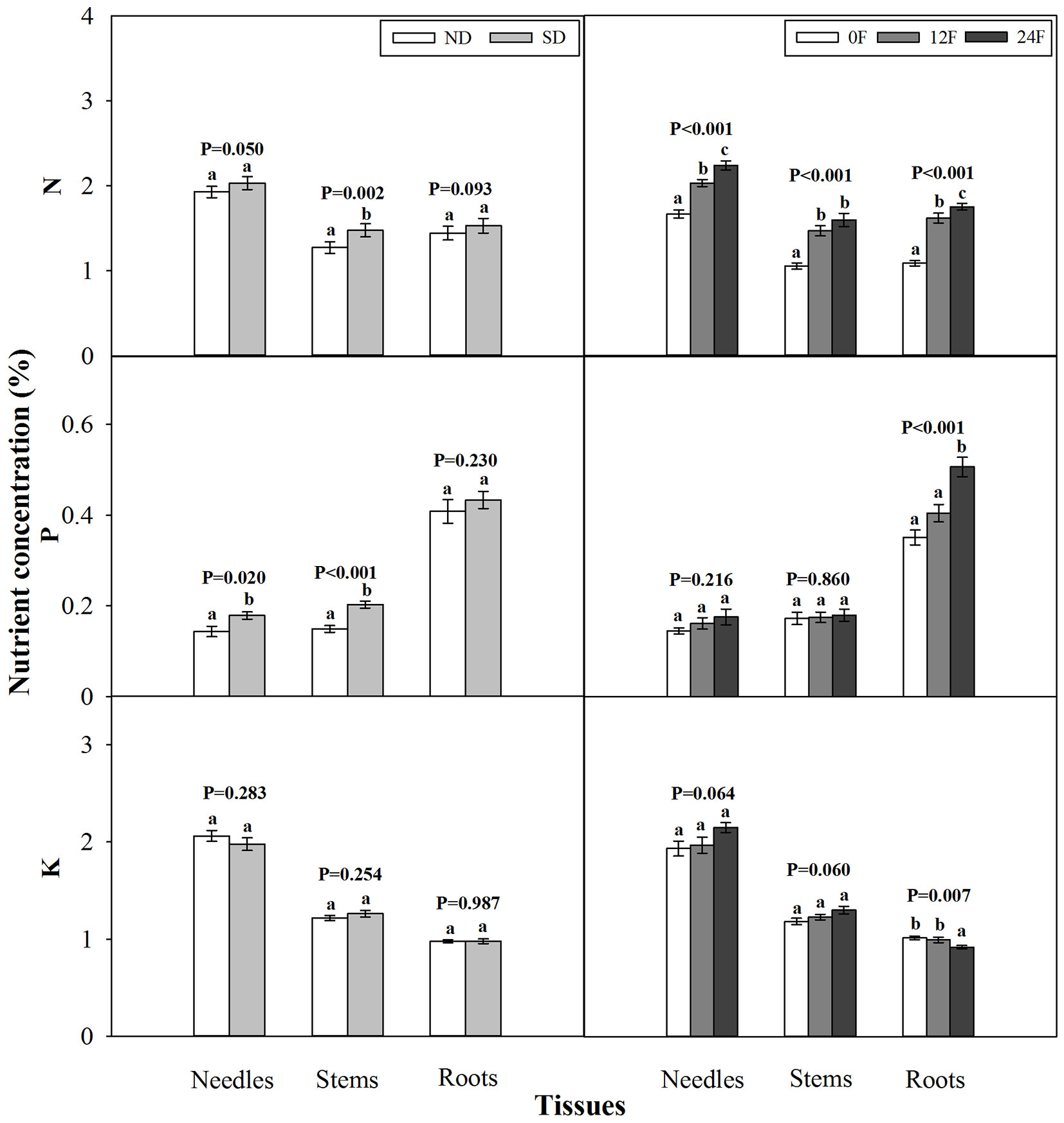

At the end of the growing season, photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization did not interact significantly to affect tissue dry mass (p = 0.080 - 0.739) or nutrient concentration (p = 0.071 - 0.847). Short-day treated seedlings had less dry mass in needles and stems, while fall fertilization rates, applied across the trial, did not affect seedling dry mass (Fig. 3). Dry mass and nutrient concentration in roots was not influenced by photoperiod treatment (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Short-day treated seedlings exhibited greater N concentrations in stems, and P concentrations in needles and stems (Fig. 4). Tissue N concentration consistently increased with increasing rates of applied N. Although all seedlings received the same amounts of P and K fertilizers (39 mg P and 49.5 mg K per seedling), the highest N rate benefited root P concentration but adversely affected root K concentration.

Fig. 3 - Tissue dry mass of Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings in relation to photoperiod treatment (ND: natural day length; SD: short-day; n=15; left) and nursery fall fertilization (0F, 12F, 24F: 0, 12, and 24 mg N/seedlings, respectively; n=10; right) at the end of the growing season. Different letters above the bars within tissues indicate statistically significant differences according to Duncan’s test at the 5 % level. P values from the ANOVA for main effects of photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization were provided due to lack of significant interactions.

Fig. 4 - Total nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) concentration (mean ± SE) in tissues of Pinus tabulaeformis container seedling in relation to photoperiod treatment (ND: natural day length; SD: short-day; n=15; left) and nursery fall fertilization (0F, 12F, 24F: 0, 12, and 24 mg N/seedlings, respectively; n=10; right) at the end of the growing season. Different letters above the bars within tissues indicate statistically significant differences according to Duncan’s test at the 5% level. P values from the ANOVA for main effects of photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization were provided due to lack of significant interactions.

Spring bud break

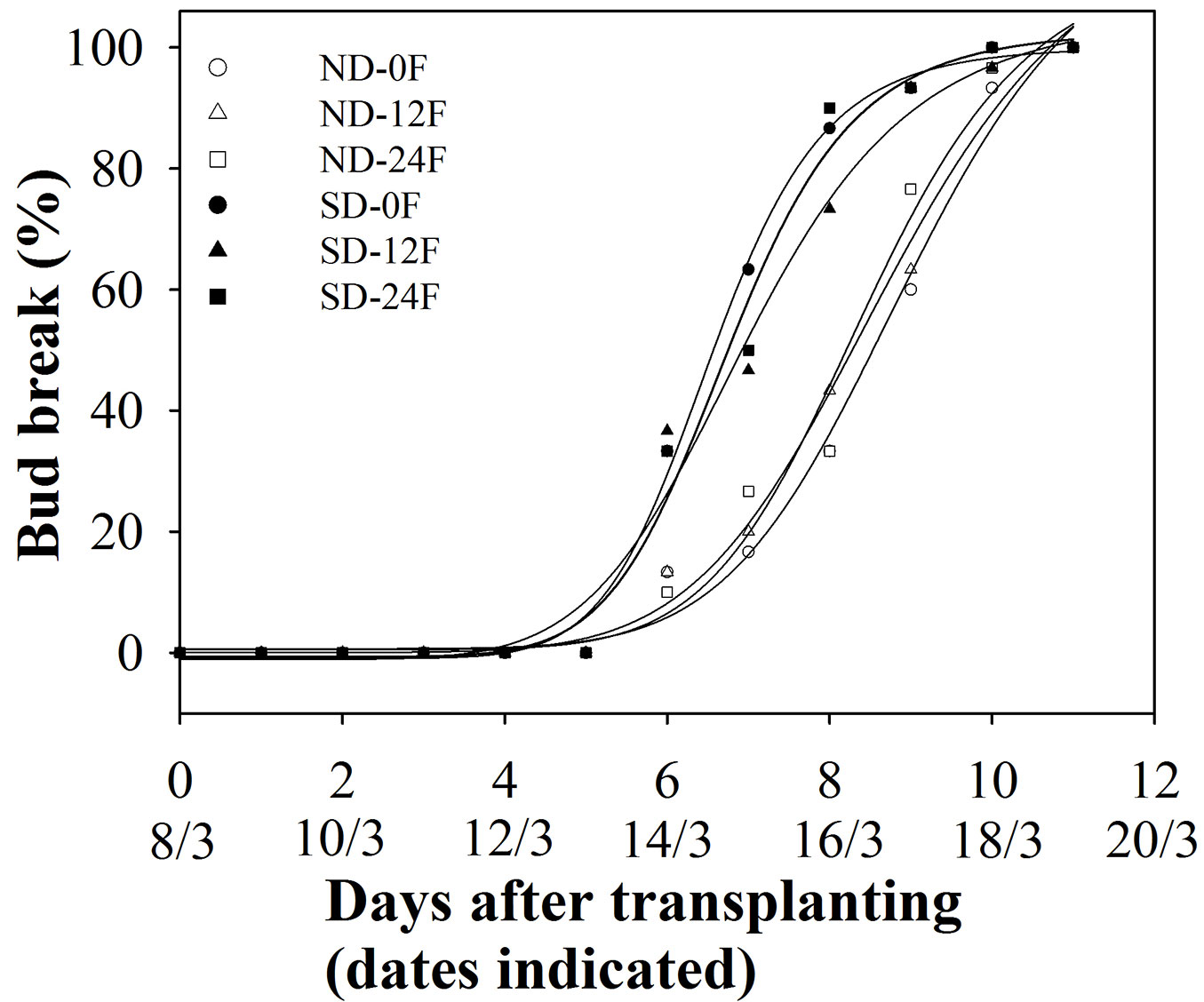

Seedlings treated with short-day treatment had a slightly earlier spring bud break (Tab. 3, Fig. 5) with numbers of days to reach 50 % and 95 % bud break being 1.5 days and 1.1 days earlier, respectively, than seedlings that were grown under natural day length. Fall fertilization and its interaction with short-day treatment did not affect spring bud break (Tab. 3, Fig. 5).

Tab. 3 - Numbers of days to 50% and 95% bud break in relation to photoperiod treatment (ND: natural day length; SD: short-day) and fall fertilization (0F, 12F, 24F: 0, 12, and 24 mg N/seedlings, respectively) when Chinese pine seedlings were transplanted into sand-filled pots and cultivated in a heating-controlled greenhouse in the following spring.

| Group | Treatment | 50% of bud break (days) |

95% of bud break (days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoperiod treatment (PT) |

ND | 8.3 | 10.2 |

| SD | 6.8 | 9.1 | |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.019 | |

| Fall fertilization (FF) |

0F | 7.6 | 9.7 |

| 12F | 7.6 | 9.8 | |

| 24F | 7.5 | 9.5 | |

| P value | 0.894 | 0.784 | |

| PT×FF | P value | 0.701 | 0.561 |

Fig. 5 - Accumulated bud break frequency (n=30) of Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings in relation to the combination of photoperiod treatment (ND: natural day length; SD: short-day) and fall fertilization (0F, 12F, 24F: 0, 12, and 24 mg N/seedlings, respectively). Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings were recorded as bud break when bud scales had diverged but needles had not elongated.

Discussion

Effect of photoperiod treatment on nutrient status

Reduced shoot dry mass in short-day treated seedlings has been observed in other studies ([3], [5], [10]). Additionally, short-day treatment affected Chinese pine seedling nutrient status, promoting an increase in needle P concentration but a decrease in needle and root K concentration. In contrast, short-day treatment had little influence on foliar nutrient concentration of Picea abies seedlings ([8]). Previous studies have shown that field performance is related to P concentration ([35]) and tissue K concentration ([1]). Thus, differentiated nutrient concentration among tissues for short-day treated seedlings may affect field performance of summer-planted seedlings. This warrants future study.

Combined effects of photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization on seedling status

During hardening, plants continue to assimilate and allocate carbon despite cessation of shoot growth ([32]). This was confirmed by the increased tissue dry mass (47%-325%) of Chinese pine seedlings from the end of photoperiod treatment to the end of the growing season in our study. Substantial growth in dry mass caused decreased tissue nutrient concentration of Chinese pine seedlings at the end of the growing season, which was attributed to nutrient dilution ([36], [32], [4]). Interestingly, we found that greater nutrient concentration of natural day treated seedlings at the end of photoperiod treatment vanished at the end of the growing season. Stem N and P concentration even increased for short-day treated seedlings relative to natural day treated seedlings at the end of the growing season. This response demonstrated that seedling developmental phases should be considered when assessing nutrient concentration changes due to shortening photoperiod. At the end of the growing season, short-day treated seedlings generally exhibited increased shoot nutrient concentration (stem N, P in needles and stems) and reduced shoot dry mass (needles and stems), indicating that the effect of short-day treatment on seedlings was tissue-specific.

Needle N concentration (1.7%) from 80 mg N per seedling treatment (0F) fell within the general recommended foliar N range 1.4%-2.2% ([22]). Increased needle N concentration by additional N fertilization during hardening was observed in Chinese pine as well as other coniferous tree seedlings ([36], [14], [18]). Chinese pine foliage N concentration (2.0% and 2.2%) resulting from fall fertilization fell into adequate level according to the criteria (≥2.0%) by Daniels & Simpson ([6]) but did not indicate luxury consumption based on the definition (>2.5%) by Dumroese ([7]). Simultaneously, enhanced stem and root N concentration was found in fall fertilized seedlings of Chinese pine and other Pinus spp. ([36], [14], [15]).

The greatest fall-applied N (24F) favored P concentration but decreased K concentration in roots, although all seedlings received the same amounts of P and K fertilizers during fall. Previous studies also showed that supplemental N during fall enhanced P concentration in roots of Pinus elliottii var. elliottii (Engelm.) ([14]) even though P and K fertilizers were not added. Conversely, tissue P and K concentration was not affected by fall applied N fertilizer in Pinus taeda L. ([36]).

Relation of photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization to spring bud break

Short-day treatment resulted in a slight advancement of spring bud break, in accordance with most studies ([3], [19], [9]), but in contrast to Fløistad’s study ([8]) that indicated that no significant differences between short-day and natural day treated seedlings. The difference in number of days to 50 % spring bud break between short-day and natural day seedlings was less than two days for Chinese pine in our study, far less than that reported for Picea abies seedlings (4-6 days - [9]), even though both species were transplanted into controlled environments. These results may be linked to differences in latitudes between species seed sources. Number of days to 50 % spring bud break in our Chinese pine (6.8-8.3 days) was much less than in Picea abies (18.1-23.1 days - [8], [9]). The ratio of accelerated days to total spring bud break days in natural day conditions (i.e., relatively accelerated days of spring bud break) should therefore be considered to compare spring bud break among tree species. Earlier spring bud break can result in satisfactory field performance ([9]), but late-spring frost that coincides with the sensitive phase of spring bud break and shoot elongation is of concern, especially at high latitudes ([24]). Under natural conditions, relatively low and diurnally fluctuating temperature might have delayed bud break further than was observed in our study. Thus, spring bud break should be monitored under natural conditions in future research in order to ensure operational and biological relevance for Chinese pine.

In contrast to other studies ([2], [41]), superior nutrient storage by fall fertilization failed to accelerate spring bud break in the present study. This might be attributed to the relatively quick spring bud break (11 days after transplanting) of Chinese pine and the role of fall fertilization might not be observable in such a short period of time.

Photoperiod treatment and fall fertilization effects on height growth increment

At the end of photoperiod treatment, short-day treatment decreased height of Chinese pine, as also demonstrated in Picea abies, and Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii (Mirb.) Franco ([29], [16], [9]). In our study, when seedlings were further reared in the nursery after short-day treatment and re-exposed to natural night length, short-day treated seedlings had greater height growth increment (0.9 cm) relative to natural day (0.1 cm). The fact that a second flush did not appear indicated that these differences in height growth increment might be attributed to larger expansion of the terminal bud (i.e., apical meristematic activity - [37]) or to greater intercalary growth of the internodes (i.e., intercalary meristematic activity - [45]) for short-day treated seedlings. Thus, measuring both terminal bud length and shoot length (from ground line to the base of the terminal bud) is recommended in future research to clarify the relation between height growth increment and short-day treatment. By the end of growing season, however, height growth increment was minor relative to total height (natural day 12.7 cm, short-day 11.0 cm).

We observed that fall fertilization did not lead to a second bud flush; avoiding autumn bud flush is preferred for nursery management ([10]). Simultaneously, greater height growth increment was detected at the high N rate, similar to findings with Pinus resinosa Ait. ([15]) and Larix olgensis ([26]), but in contrast to Pinus elliottii var. elliottii and Pinus taeda in which heights were not affected by fall fertilization ([36], [14], [42]). Islam et al. ([15]) seedlings demonstrated that fall fertilization of Pinus resinosa resulted in a swollen terminal bud (i.e., 9 mm vs. 18 mm for non-fertilized and fertilized seedlings, respectively).

Caveats and imitations

Similar to other studies of photoperiod manipulation and fall fertilization, we did not examine treatment effects on seedling non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) accumulation. This has potential to affect seedling field survival and stress resistance ([21], [44]). Future studies should be designed to examine effects of these nursery cultural treatments alone and in combination as a means to optimize loading of both nutrients and NSC in seedlings, especially when targeted for harsh outplanting sites ([17], [44]). Finally, implementation of short-day treatments in the nursery has potential to affect environmental variables beyond photoperiod, which may create experimental confounding. For example, the blackout curtains used in our study might raise day/ night temperatures relative to natural day length. While logistically difficult to control, these effects should be monitored and minimized whenever possible to ensure impartial evaluation of treatment effects.

Conclusions

Similar to findings in other forest tree species, a three-week short-day treatment initiated in late July effectively ceased shoot growth, induced bud set, and reduced shoot dry mass of Chinese pine. At the end of photoperiod treatment, short-day treatment increased foliar P concentration but decreased foliar and root K concentration. Conversely, enhanced stem N and P concentration, and foliage P concentration consistently occurred in short-day treated seedlings at the end of the growing season. Variable responses indicated that effects of short-day treatment on nutrient concentration might be linked to seedling developmental phases. Fall applied N was a useful tool for enhancing Chinese pine tissue N and root P concentration, but the combination of short-day treatment and fall fertilization did not yield interact to effect nutrient storage dynamics. Short-day treatment rather than fall fertilization advanced spring bud break, though this effect was of little biological significance. Our results suggest that short-day treated seedlings, characterized by relatively low shoot:root yet high shoot N and P concentration, would be advantageous for outplanting on drought-prone sites.

Acknowledgements

The study was jointly funded by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation Program (Contract No. 6132023), National Natural Science Fund (Contract No. 31670638), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Contract No. TD 2011-8). Special thanks to Dr. Steve C. Grossnickle for editing English language and providing technical assistance. We gratefully acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments of the manuscript.

References

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Guolei Li

Beijing Laboratory of Urban and Rural Ecological Environment; Key Laboratory for Silviculture and Conservation, Ministry of Education, Beijing Forestry University, 35 East Qinghua Road, Haidian District, Beijing 100083 (China)

Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907-2061 (USA).

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Pan J, Jacobs DF, Li G (2017). Combined effects of short-day treatment and fall fertilization on growth, nutrient status, and spring bud break of Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings. iForest 10: 242-249. - doi: 10.3832/ifor2178-009

Academic Editor

Claudia Cocozza

Paper history

Received: Jul 25, 2016

Accepted: Dec 20, 2016

First online: Feb 11, 2017

Publication Date: Feb 28, 2017

Publication Time: 1.77 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2017

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 48580

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 40687

Abstract Page Views: 2878

PDF Downloads: 3598

Citation/Reference Downloads: 38

XML Downloads: 1379

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 3306

Overall contacts: 48580

Avg. contacts per week: 102.86

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2017): 4

Average cites per year: 0.44

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Combined pre-hardening and fall fertilization facilitates N storage and field performance of Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings

vol. 9, pp. 483-489 (online: 07 January 2016)

Research Articles

Links between phenology and ecophysiology in a European beech forest

vol. 8, pp. 438-447 (online: 15 December 2014)

Research Articles

Nursery fertilization affected field performance and nutrient resorption of Populus tomentosa Carr. ploidy levels

vol. 15, pp. 16-23 (online: 24 January 2022)

Research Articles

Effects of nitrogen loading under low and high phosphorus conditions on above- and below-ground growth of hybrid larch F1 seedlings

vol. 11, pp. 32-40 (online: 09 January 2018)

Research Articles

Soil nutrient status, nutrient return and retranslocation in poplar species and clones in northern Iran

vol. 6, pp. 336-341 (online: 29 August 2013)

Technical Reports

Nursery practices increase seedling performance on nutrient-poor soils in Swietenia humilis

vol. 8, pp. 552-557 (online: 09 December 2014)

Research Articles

Nutrient uptake, allocation and biochemical changes in two Chinese fir cuttings under heterogeneous phosphorus supply

vol. 11, pp. 411-417 (online: 05 June 2018)

Research Articles

Substrates and nutrient addition rates affect morphology and physiology of Pinus leiophylla seedlings in the nursery stage

vol. 10, pp. 115-120 (online: 02 October 2016)

Research Articles

Response of artificially defoliated Betula pendula seedlings to additional soil nutrient supply

vol. 10, pp. 281-287 (online: 13 December 2016)

Research Articles

Local neighborhood competition following an extraordinary snow break event: implications for tree-individual growth

vol. 7, pp. 19-24 (online: 14 October 2013)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword