Natural spread of Verticillium wilt as effective constraint on Ailanthus altissima invasion

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 18, Issue 6, Pages 391-398 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor4843-018

Published: Dec 22, 2025 - Copyright © 2025 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle (tree-of-heaven) is a widespread tree classified as an invasive alien species in the European Union. Recently, severe wilt decay from Verticillium spp. infections in A. altissima trees has been reported in both Europe and the USA. In Italy, the disease was first observed in Trentino-South Tyrol in 2017. Since then, the progression of infection foci has been monitored, and the pathogens involved have been isolated and characterized at the molecular level. Between 2017 and 2022, the number of disease foci increased to 171, affecting entire valleys in this mountainous region. The foci appear unaffected by environmental conditions and impact trees in urban, peri-urban, and wooded areas. Attacks targeted both individual trees and clusters of various size. Dead plants were detected in 138 foci, and in some cases, complete disappearance of A. altissima was reported. Infected or dead seedlings/saplings were also observed in 97 foci. Verticillium dahliae was isolated from 103 foci and confirmed through real-time PCR assays using the VertBT primer. No wilting symptoms were observed in other tree species near the affected A. altissima individuals. Inoculation tests on A. altissima seedlings confirmed the pathogenicity of the isolates, while vine and apple seedlings showed no effects. The natural spread of V. dahliae foci proved very effective, showing few limitations in controlling A. altissima. Therefore, reporting and monitoring the natural spread of wilt could represent a preliminary response to the EU’s request to combat the invasion of A. altissima.

Keywords

Tree-of-Heaven, Decline, Invasive Species, Natural and Biological Control, Landscape Ecology

Introduction

Native to China and commonly known as the Tree-of-Heaven, Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle has been introduced in over 50 countries across all continents, except Antarctica, and is invasive in Italy and 22 other countries ([14], [38]). A. altissima was introduced in France in the 18th century as an ornamental and shade tree ([9], [36]), and has since been spread to other parts of central and southern Europe. In Italy, A. altissima was introduced to the Botanical Garden of Padua in 1760. It was later used for silk production and railroad construction, subsequently spreading throughout the country ([3]). In the Trentino-Alto Adige region , it began to spread spontaneously starting in 1856 ([23]).

A. altissima is now recognized as an invasive species and has been reported to adversely impact native plant communities in Italy ([17]). It is the most common non-native plant species in urban areas ([14]). Further impacts of A. altissima invasion include alterations to soil and litter fauna caused by root suckers, which disrupt soil community dynamics and ecosystem functioning ([25]). Moreover, A. altissima presents additional problematic traits in urban environments, including allergenic pollen, caustic leaves, and an unpleasant odor from its male flowers ([36]).

A. altissima is challenging to control once it has established ([37]). These trees produce a large number of seeds that have a high germination rate and can be dispersed over long distances, mainly by wind ([16]). Additionally, they can propagate through lateral roots and can regenerate from root suckers after being cut down ([26]). Associated with its versatile reproductive strategies, A. altissima exhibits allelopathic effects due to toxic root exudates that may inhibit the growth of other plants, contributing to its aggressiveness and persistence in the environment ([8]). These adaptive traits promote successful colonization and competitive exclusion of native species, ultimately making A. altissima one of the most invasive species. In 2019, the species was included on the Union list of Invasive Alien Species (IAS) of Union concern, thereby subjecting it to monitoring and control across all EU member states ([15]).

Despite its high tolerance for adverse environmental conditions, A. altissima is vulnerable to biotic agents. In recent decades, diseased or dead plants have been observed exhibiting symptoms of wilt decay, including wilting leaves, premature defoliation, terminal dieback, yellow vascular discoloration, and mortality ([27]). Representatives of the genus Verticillium have been reported as the primary pathogen causing extensive mortality of A. altissima in many countries. Verticillium nonalfalfae Inderb. previously identified as V. albo-atrum Reinke & Berthold ([10]) and V. dahliae Kleb. were isolated in the USA ([35]), Austria ([21]), and Spain ([24]). Only V. dahliae was isolated in Hungary ([12]) and in Northern Italy ([19]). Similarly, Pisuttu et al. ([28]) isolated only V. dahliae, which causes wilt of A. altissima in Tuscany, Central Italy. More recently, V. dahliae was reported in naturally declining stands in Slovakia ([33]).

The emergence of Verticillium-based diseases presents a new opportunity to control the spread of A. altissima, paving the way to potential biological control methods. In this context, the pathogen V. nonalfalfae is regarded as more aggressive than V. dahliae ([27]). It has been suggested as a promising biological control method ([13]) to help mitigate the impact of A. altissima on native plant communities. In fact, V. nonalfalfae is the active ingredient in an approved mycoherbicide (Ailantex®) in Austria ([6]) and in other European countries.

However, the natural spread of the disease underscores the need for targeted investigations to understand its actual impact and potential as a control method for this invasive tree. In this study, we present the results of a six-year monitoring effort on the progression of A. altissima wilt disease in the Trentino-South Tyrol regions (Northern Italy). The study has three main goals: (i) to assess the spread and frequency of wilting and the associated decline of A. altissima in this alpine region; (ii) to examine any potential correlation between environmental variables and A. altissima decline; (iii) to identify the Verticillium species involved in the disease foci development and evaluate their pathogenicity.

Material and methods

Field surveys

The surveys were conducted in Trentino-South Tyrol (13.607 km2), located in the southern part of the Eastern Alps. The presence of A. altissima has been reported since the 19th century, with trees now primarily recorded in the valley bottoms and some areas between forests on the slopes. A detailed map A. altissima distribution has not yet been produced due to its irregular and patchy occurrence, typically found in small groups of plants or as individual trees. However, botanical records of the species’ presence were available and mapped ([31]), serving as the basis for locating existing stands.

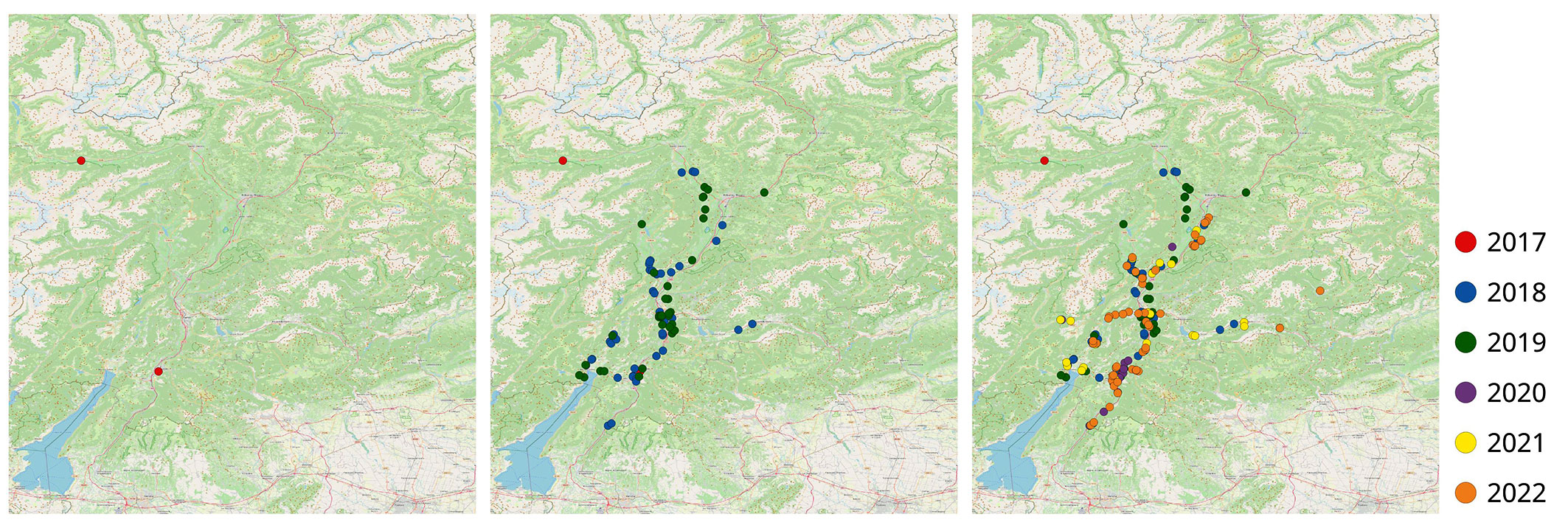

Most A. altissima plots were easily visible along roads, rivers, and railroads in the valley bottoms, making continuous monitoring of the decline easier (Fig. 1). Staff from the Forest and Fauna Service of the Autonomous Province of Trento and the Department of Forestry of the Province of Bolzano provided valuable and detailed information to locate A. altissima nuclei and affected trees in woods and landscapes.

Fig. 1 - Maps of sampled sites in Trentino-Alto Adige in 2017 (left), 2019 (middle) and 2022 (right). Infected sites detected each year were identified with different colors (© OpenStreetMap contributor).

The presence of the disease was evaluated through continuous monitoring during the vegetative periods (June-November) from 2017 to 2022. For each infected site, the following data were collected: general site characteristics, altitude, aspect, slope (%), substrate (calcareous/siliceous), soil depth (superficial, deep), position (ridge, slope, valley bottom), and type of A. altissima stand (pure or mixed; single tree, small group - 2 to 10 trees -, or large group - more than 10 trees).

Disease presence was assessed by examining the entire crown for dead or suffering leaves and branches. It was also confirmed by checking for characteristic orange to brown discoloration of the first wood tissues under the bark on the stem or branches. The impact of the disease was recorded as (i) a single tree affected, (ii) a small group (two to 10 infected trees), or (iii) more than 10 trees infected. The presence and number of dead trees were also recorded.

Regeneration of A. altissima was recorded at each site, along with observations of disease-related damage on symptomatic or dead individuals. Other tree species within a 30-meter range from the foci were also assessed for any symptoms of stress. In addition, potential disturbance factors, such as wildfires, trampling, damage caused by game or livestock, anthropogenic disturbance, and rockfalls, were considered and excluded. The plots were localized with a high-precision GPS device, and all data were directly recorded using a digital field mapping app, SMASH Smart Mobile App for the Surveyor’s Happiness (⇒ https://www.geopaparazzi.org/ - available for both Android and iOS platforms), which allows users to create customized survey forms. A dedicated form was developed explicitly for this study.

Infected plots located approximately 100 meters apart were considered as separate sites. In each plot, a sample of bark or branches was collected from a single symptomatic plant for molecular analysis. In 14 plots, no samples were collected because the plants were not accessible.

An exploratory data analysis (EDA) was conducted to identify patterns and characterize the geographic distribution of disease foci. The data was first prepared for analysis by identifying and separating categorical variables for targeted examination. Key descriptive statistics were computed, and several comprehensive visual summaries were generated using a combination of plots and charts. These visualizations provided an overview of the data and were instrumental in revealing patterns, anomalies, and potential areas of interest for further investigation.

Correlations between disease foci and environmental factors, such as altitude, aspect, slope, bedrock type (calcareous/siliceous), soil depth (superficial/deep), and topographic position (ridge, slope, valley bottom), were examined. The analyses were conducted separately for continuous and categorical variables.

Regarding continuous variables, since altitude and slope were not normally distributed, the non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation test was applied to verify any associations between each environmental variable and the presence of the following symptoms: leaves wilting (A), wood discoloration (B), and dead plant (C). Each symptom category was binarized (1 = present, 0 = absent), and correlations were tested separately for each category.

For categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test was preferred over the Chi-square test, due to the low expected frequencies, to ensure valid statistical inference. To further assess the strength of these associations, we calculated Cramér’s V coefficient, which measures the effect size of the relationship between two factorial variables using the “rcompanion” package ([20]). All analyses were performed in R ([32]).

Fungal isolation

Wood samples from 30 symptomatic plants were cut into 5-cm-long pieces and surface-sterilized by dipping them into a 2% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) solution for 60 seconds, followed by rinsing in sterile distilled water for 30 seconds. After removing the bark, samples were examined for noticeable tissue discolorations, and fragments were excised from these zones and placed onto Petri dishes containing Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA, Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) amended with 0.40 mg L-1 Chloramphenicol (Sigma-Aldrich). Five fragments were placed on each plate, and two plates were prepared for each sample. Segments of 30 symptomatic stems or branches were also put in a moist chamber (4-5 pieces in Petri dishes with a diameter of 90 mm, containing moistened filter-paper). Petri dishes were sealed with Parafilm® “M” (Pechiney Plastic Packaging, Menasha, WI, USA) and incubated at 21 °C in the dark for 14 days. Resulting isolates morphologically resembling Verticillium spp. were subcultured and incubated under the same conditions.

Pathogenicity test

Four isolates of V. dahliae (numbers 2, 8, 11, 23 - see Tab. S1 in Supplementary material) obtained from affected adult trees in 4 different areas and verified by molecular tools were used in the pathogenicity test following the method described in Scala et al. ([34]). One-to two-year-old seedlings of A. altissima were collected in the field and transplanted into pots with standard nursery substrate. For each isolate, mycelial plugs were cut from the edges of seven-day-old cultures and placed into 4-mm-diameter circular wounds in the seedlings, with the mycelial surface facing the cambium. Inoculated holes were sealed with Parafilm to avoid contamination or desiccation. Six A. altissima seedlings were inoculated for each isolate, while six seedlings were used as controls. Two of the strains (number 2 and 11) were inoculated on 4-year-old plants of vine (Pinot Nero extav115, grafted on Kober 5 Bb) and apple (Fujion grafted on M9), with six replicates, using the method described above.

Seedlings and plants were placed in a climate-controlled chamber at 24 °C and were regularly irrigated. Inoculation was carried out in July 2019 and checked weekly for five months. The results of inoculation were assessed by examining for the presence of orange-brown tissue beneath the bark and wilted foliage. From inoculated subjects, re-isolation was performed, and the resulting cultures were morphologically identified as V. dahliae.

DNA extraction from fungal mycelium and plant tissue

Fungal mycelium was scraped with a sterile scalpel blade from the cultures obtained on PDA plates. The mycelium was homogenized using a Mixer Mill MM 300 (Retsch GmbH, Germany) in 2 mL reaction tubes, each containing a 3 mm tungsten carbide bead (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and 180 µL Lysis Buffer T1 provided with the NucleoSpin™ Plant II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), which was used to extract the total nucleic acid according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For DNA extraction of wood segments, 1 g of the same samples used for fungal isolation was lyophilized for 24 hours, ground in sterile stainless-steel jars using a mixer-mill disruptor (MM 400, Retsch, Germany) at 25 Hz for 45 seconds. Then, 50 mg of the fine powder obtained were used for DNA extraction following the protocol described above. The concentration of DNA from fungal mycelia and plant tissue was measured using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) with the High Sensitivity DNA Assay Kit, and the samples were stored at -20 °C until further analysis.

PCR amplification and sequencing

For molecular identification of the fungal strains, the ITS region and 5.8S gene of the rDNA were amplified by PCR using primer pairs ITS1-F ([7]) and ITS4 ([39]). The 25 µL PCR reaction mixture included 12.5 µL of GoTaq™ Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 9.5 µL of water supplied with the GoTaq, 0.4 µM of each primer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 1 µL of DNA. Negative (sterile water) and positive controls (V. dahliae strain Vd_BZ1, Accession no. MH607412 - [19]) were included in all PCR runs. Cycling was carried out in a Biometra 96 Professional thermocycler (Biometra, Gottingen, Germany) with an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 30 seconds, and elongation at 72 °C for 45 seconds, with a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR fragments were analyzed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis in 1× Tris-boric acid-EDTA buffer (TBE), stained with SYBR Safe® (Life Technologies, Milan, Italy), and visualized under UV light. The GeneRuler® DNA ladder mix (Thermo Scientific) was used as a size standard. PCR products were sent to the Sequencing Platform of Fondazione Edmund Mach for sequencing. The obtained DNA sequences were analyzed using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) against reference ITS sequences in GenBank.

Real-time PCR detection

To detect V. dahliae in plant tissue, Real-time PCR was performed using the primer pair VertBtF/VertBt-R, derived from the β-tubulin gene sequence ([2]). Amplification was performed in a 20 μL final reaction volume containing 3 μL DNA template, 10 nM each primer, 10 μL SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG (Thermo-Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), and sterile nuclease-free water to reach the appropriate volume. DNA from V. dahliae Vd_BZ1 was used as a positive amplification control at a constant concentration (0.5 ng µL-1) in each run. Nuclease-free water served as the negative control. Two replicates were run for each plant DNA sample, positive and negative. Amplifications were performed in a LightCycler® (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 seconds and 63 °C for 35 seconds. Fluorescence was measured once per cycle at the end of the extension step, and Cq values were automatically determined by the device. For each sample, the average Cq, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation were determined. Samples with a mean quantification cycle (Cq) value lower than 30 and a melting curve peak similar to the positive control were considered V. dahliae positive. The entire experiment was carried out twice independently.

Results

Field surveys

After the first two foci observed in 2017 ([19]), a progressive increase in the number of affected stands was recorded: 44 in 2018, 34 in 2019, 13 in 2020, 24 in 2021, and 54 in 2022, resulting in a total of 171 affected sites (Tab. S1 in Supplementary material). Although the low number of detected sites in 2020 was likely due to reduced surveying during the pandemic, a clear increase and significant epidemic spread of the disease were observed in the central valley of the region (Fig. 1).

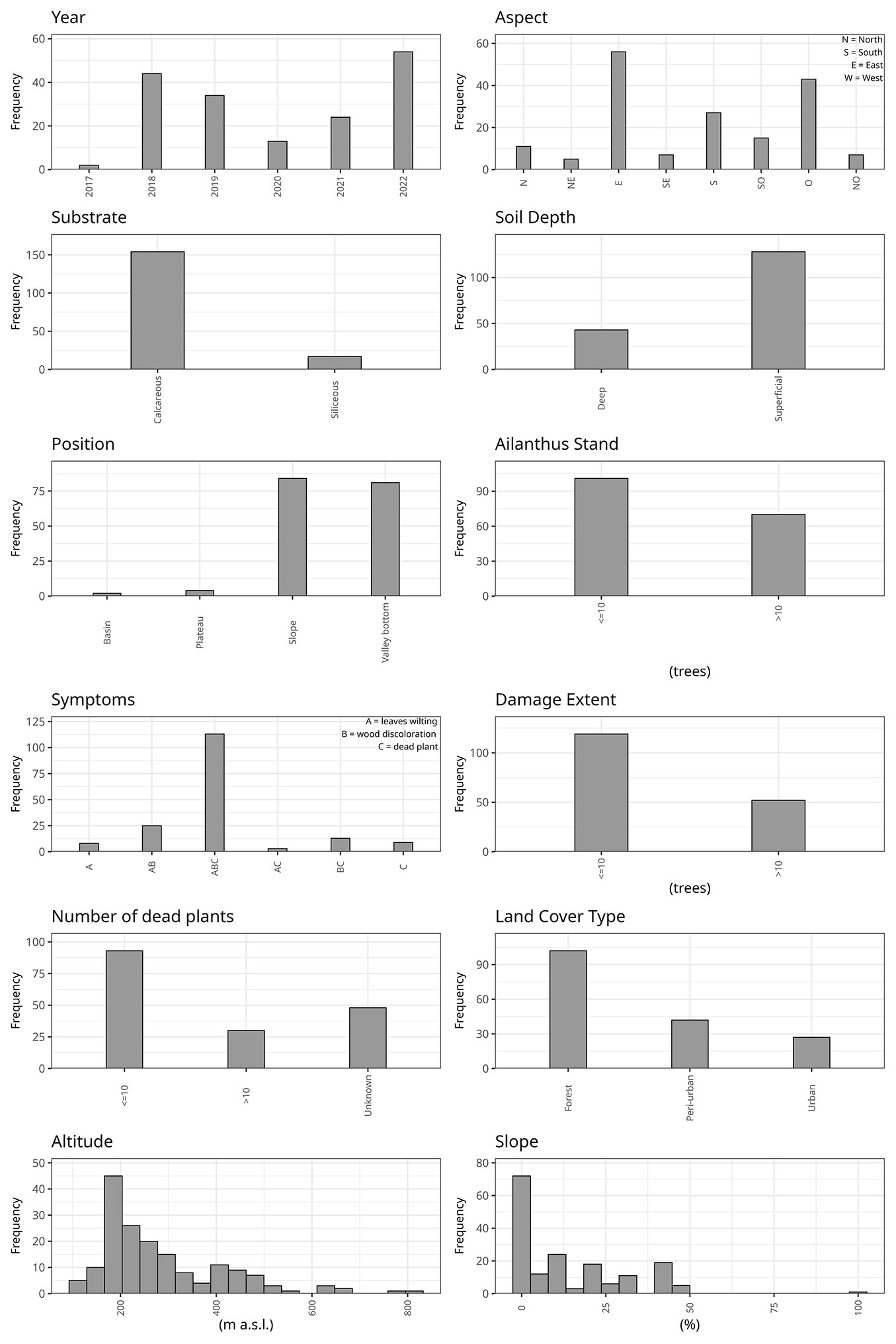

The infection spread was particularly evident along the main roads, where symptomatic or dead trees became increasingly visible from year to year. The disease was observed in trees growing at altitudes ranging from 99 to 803 m a.s.l., mainly on plains or moderate slopes. However, two foci were recorded on trees colonizing vertical cliffs above roads (no. 110 and no. 130 in Tab. S1). All aspects were affected by the presence of declining trees, with a slight prevalence on the east and west slopes, reflecting the presence of A. altissima along the central valley slopes. A higher percentage (90%) of foci occurred on calcareous soil, consistent with the dominant pedological features of the valleys. Almost half of the foci were found on slopes, while the remainder were located at the valley bottoms. The disease was observed in woodland in 102 cases (60%), mainly on trees at forest edges, but in a few cases also on groups of trees growing in the forested areas (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 - Site characteristics and damage incidence of Ailanthus altissima wilt foci. Each panel corresponds to one variable: Year, Aspect, Substrate, Soil Depth, Position, Ailanthus stand, Symptoms, Damage extent, Number of dead plants, Land cover type, Slope, and Altitude. Symptoms were classified into three disease categories: A (leaves wilting), B (wood discoloration), and C (dead plant). Combinations (e.g., AB, ABC) denote co-occurrence of symptoms. The damage extent represents the degree of visible damage assessed in the field (0-3 scale).

Forty-two foci (24%) were detected on trees growing in peri-urban areas, mainly along roads. The remaining 27 foci (16%) were in parks, private gardens, or along urban streets; in a few cases, the disease affected A. altissima colonizing abandoned areas within urban environments. None of the recorded characteristics of the foci were statistically significant in explaining their distribution.

In 119 foci (70%), the disease affected single trees or small groups of fewer than 10 plants, whereas in the remaining 52 foci (30%), more than 10 plants were affected. Dead plants were detected in 138 foci: 1 to 10 dead plants were counted in 108 foci, while in 30 foci, the dead plants were > 10, reaching up to 20 or more in a few cases. Natural regeneration of A. altissima was observed in 146 foci, with suffering or dead plants occurring in 97 of them (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 - A dead group of Ailanthus altissima. Note the spread of the disease in the regeneration (red arrow).

Other species besides A. altissima were present in 95 foci; no symptoms were detected on these trees, which appeared healthy. Robinia pseudoacacia was the most common species associated with A. altissima, occurring in 63 foci, confirming the role of both non-native species in forming secondary woods. Among the other recorded species, Acer spp. was reported in only three sites without any symptoms. Remarkably, some of the foci were located at the edge of vineyards or apple orchards, but these cultivated plants showed normal development and no symptoms of Verticillium wilt.

The decline starts with wilted leaves appearing in the upper crown (Fig. 4); even when still green, they appear collapsed and quickly die, falling and leaving a defoliated branch. The crown shows wide hollows, although new, smaller, and incomplete foliage may occasionally develop. Dead branches and crown dieback are clear indicators revealing distressed trees from afar. Under the bark of the stem and branches, there is the characteristic discoloration of the first layers of wood, which appear completely or partially orange-brown (Fig. 5). Dead branches and stems are quickly colonized by other parasites such as Schizophyllum commune Fr., Armillaria spp., and Peroneutypa scoparia (Schwein.) Carmarán & A.I.Romero. Suffering trees generally die within a few months and, in some cases, death is rapid. However, a few cases of declining trees that survived for several years were also observed. The spread of the disease was evident both in the enlargement of the infection area affecting nearby healthy trees and the increasing emergence of new diseased locations in adjacent A. altissima stands.

Fig. 5 - The characteristic decoloration (red circle) due to Verticillium colonization of superficial wood tissues. The arrow indicates the presence of Armillaria spp. mycelium, colonizing the dead tissues.

Exploratory data analysis did not reveal any significant correlations between diseases foci and the environmental factors examined (altitude; aspect; slope; substrate - calcareous/siliceous; soil type - superficial, deep; position - ridge, slope, valley bottom), and the kind of A. altissima stand (Tab. 1). The statistical analyses identified only a few weak and isolated associations, such as a minor negative correlation between altitude and specific symptom categories, and a moderate association between exposure and one symptom type (Tab. 2). However, most variables showed no significant correlations. Given the weakness of these associations and the context of the study, no definitive conclusions can be drawn.

Tab. 1 - Results of Spearman’s rank correlation between individual symptom categories (A: leaves wilting; B: wood discoloration; C: dead plant) and two quantitative environmental variables (altitude and slope). Binary variables were created for each symptom (1 = presence; 0 = absence).

| Symptom | Variable | Spearman ρ | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Altitude | 0.109 | 0.1575 |

| Slope | 0.055 | 0.4751 | |

| B | Altitude | -0.182 | 0.0174 |

| Slope | 0.022 | 0.7799 | |

| C | Altitude | -0.159 | 0.0380 |

| Slope | 0.004 | 0.9588 |

Tab. 2 - Results of Fisher’s exact test for the association between each symptom category (A: leaves wilting; B: wood discoloration; C: dead plant) and selected categorical environmental variables. For each pair, the p-value is reported. Where the association is statistically significant (p < 0.05), the corresponding Cramér’s V value, measuring the strength of association, is also shown.

| Symptom | Variable | p-value | Cramers’ V |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | aspect | 0.2143 | - |

| soil | 0.5900 | - | |

| substrate | 0.6966 | - | |

| position | 0.8371 | - | |

| land cover type | 0.4673 | - | |

| A. altissima stand | 0.0530 | - | |

| B | aspect | 0.1830 | - |

| soil | 0.5900 | - | |

| substrate | 0.4252 | - | |

| position | 0.6977 | - | |

| land cover type | 0.1842 | - | |

| A. altissima stand | 0.6349 | - | |

| C | aspect | 0.0065 | 0.3 |

| soil | 0.8291 | - | |

| substrate | 0.3472 | - | |

| position | 0.5940 | - | |

| land cover type | 0.3037 | - | |

| A. altissima stand | 0.2487 | - |

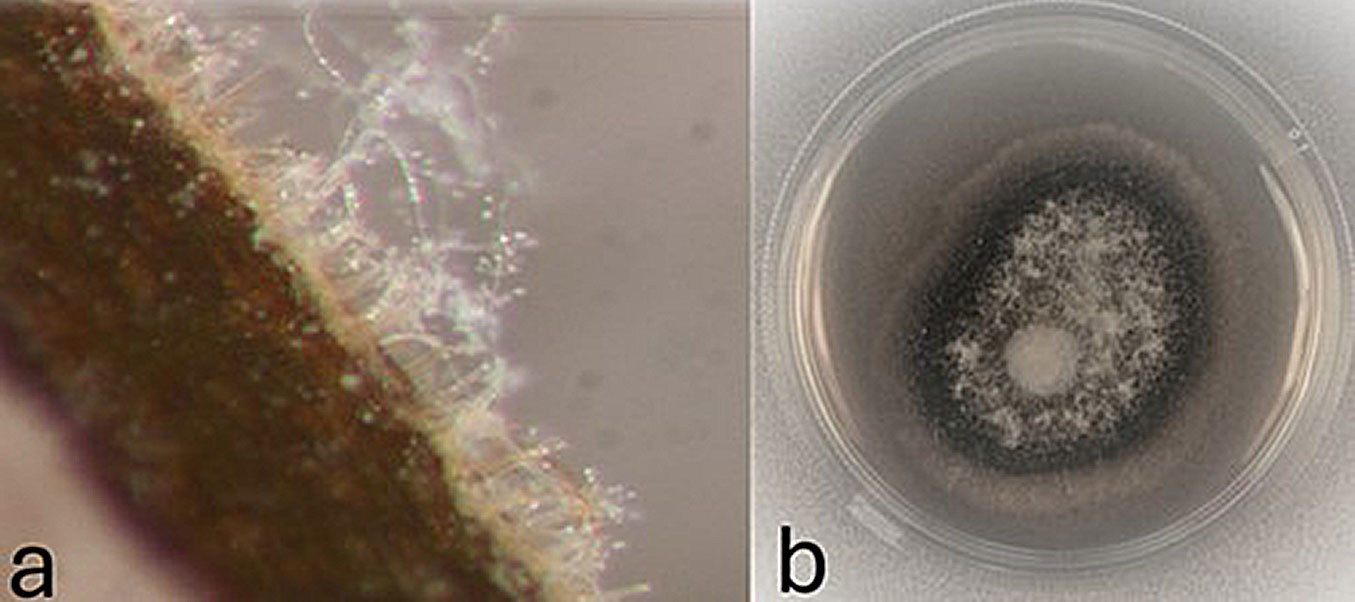

Detection of V. dahliae in plant tissue

V. dahliae was detected in 103 sampled plants (65.6%) using different methods (Tab. S1 in Supplementary material). Among them, seven isolates were obtained by culturing on agar medium and 12 others from moist chambers (Fig. 6). Isolates were identified as V. dahliae based on morphology, i.e., production of brown-pigmented microsclerotia, characteristic conidiophores, and conidia dimensions (mean ± standard deviation = 5.09 ± 0.9 × 3.9 ± 0.7 μm). Morphological identifications were confirmed by sequencing analysis of the mycelial DNA using the primer pair ITS1F-ITS4. The BLAST analysis of the ITS sequences showed 100% identity to the V. dahliae ITS sequences ON193840.1 and MN325001.1 in GenBank. Two sequences obtained in monitored sites were previously deposited in GenBank (accession no. MH607412-13 - [19]).

Fig. 6 - Mycelium and conidiophores of Verticillium dahliae grown on the surface of Ailanthus altissima wood in a moist chamber observed under stereomicroscopy (a) and fungal culture in Potato Dextrose Agar medium (b).

The SYBR® Green-based assay using the VertBt primer set amplified the plant DNA tested (Tab. S1), with cycle threshold (Ct) values ranging from 19.79 to 35. Among these, 101 out of the 155 tested plant DNA (65.1%) were considered positive for V. dahliae with Ct values < 30 and the melt derivative curves showing melt temperatures of approximately 85 °C (Fig. S1 in Supplementary material). Moreover, using gel electrophoresis, the PCR product yielded a unique DNA fragment of approximately 115 bps from the DNA extracts, whereas no amplicon was observed in the negative control. Results obtained with this primer set were consistent across replicates in both experiments.

The real-time PCR method showed a greater sensitivity in detecting V. dahliae (65.1%) than the microbiological methods (31.6%). The culture plating and moist chamber results (Fig. 6) corroborated the real-time PCR results, except for four samples in which the fungus was isolated, but qPCR did not detect it.

Pathogenicity test

Clear symptoms of disease were observed in inoculated A. altissima seedlings a few weeks after inoculation. Wilting leaves appeared after 20 days in three plants. At the end of the observation period (five months), one seedling was already dead with evidence of colonization of the under-bark tissues. Orange-brown discoloration was observed in 13 inoculated seedlings, with two cases showing the complete colonization of the stem (Fig. S2 in Supplementary material). Six of these seedlings also exhibited leaf wilting. All the tested Verticillium strains showed the same pattern of behavior. The other treated seedlings (10) remained asymptomatic, as did all the controls.

Isolation from the orange-brown tissues allowed the recovery of Verticillium colonies from all symptomatic plants. Morphological and DNA analysis confirmed that V. dahliae was the causal agent. Inoculations on apple and vine showed no symptoms during the observation period: no colonization of the stem tissues was observed near the inoculation wounds, and no foliage symptoms appeared. All the inoculation wounds were partially or totally healed after 4 or 5 months.

Discussion

The surveys conducted between 2017 and 2022 confirmed the natural spread of Verticillium dahliae on A. altissima throughout the range of this invasive species in the provinces of Bolzano and Trento (Northern Italy). The spread of V. dahliae is still ongoing, with about 40 new foci of the disease observed in additional general surveys conducted in 2023 and 2024 (G. Maresi, personal communication). These foci follow the same pattern as those studied, indicating the presence of the disease in some lateral valleys where it was not detected during the monitoring period.

V. dahliae can infect and kill both regeneration and mature trees, and it is also able to affect and destroy A. altissima regeneration in woods, urban areas, and degraded ecosystems such as along railways, roads, and walkways. Our results showed no significant environmental features influencing the widespread nature of the disease. It appears unaffected by slight differences in altitude, slope, and aspect, and is not influenced by the scattered distribution of A. altissima or the presence of other species. Moreover, the presence of foci in valleys with different mean temperatures and rainfall patterns seems to exclude the role of these climatic factors in the aftermath of wilting. The appearance of disease foci within isolated groups of A. altissima in natural woods, mainly Orno-ostrietum stands (see Tab. S1 in Supplementary material), suggests a great ability of the pathogen to reach target trees even across a discontinuous range. At the same time, its presence in some lateral valleys shows its capacity to overcome the physical barriers characteristic of the mountainous areas of the two investigated provinces. The disease progression confirms observations in other regions, such as the USA ([4]), and suggests that V. dahliae can spread over long distances. Moreover, the emergence of new foci indicates that the pathogen inoculum has remained continuously present over the years.

The pattern of progression among the affected foci calls for more detailed investigation. Transmission of the disease within foci through root anastomosis could play a fundamental role, as demonstrated by Dubach et al. ([6]). Still, it cannot explain the emergence of foci far away from the detected ones or the infection of trees growing on cliffs. Other dispersal factors may be considered, such as wildlife transporting infected soil, insects feeding on or sucking from affected plants, or wind dispersal of contaminated plant debris. Although less likely, some human activities may also contribute to the dispersal of contaminated soil and plant parts. Moreover, V. dahliae can produce resting structures that can persist in the soil for many years ([11]). Various animals can also transport these resting structures via their hooves, as well as cars, tractors, and shoe soles. The disease proved effective in killing the affected plants within a few months or a few years. The pathogen destroyed 12 diseased plots, and apparently neither A. altissima resprouting nor regeneration restored the stands. The disease’s severity is also confirmed by the high number of foci with dead plants (124). It is noteworthy that symptomatic trees are not able to produce massive flowers and seeds, thus reducing dissemination that strongly influences the spread of this invasive species ([37]). However, in a few cases, symptomatic trees survived throughout the monitoring period, suggesting possible tolerance or resistance within the natural population of A. altissima. Pisuttu et al. ([29]) have emphasized the high susceptibility and mortality associated with V. dahliae infections in several Italian A. altissima populations. Nonetheless, our field observations suggest the presence of possible resistant (or tolerant) A. altissima individuals. This needs further research either by investigating the plant-pathogen interaction or a potential effect of some environmental factors, such as temperature. It is well known that V. dahliae appears well adapted to typical Mediterranean climates; however, in the context of climate change, higher temperatures and extreme events could affect its survival or infectivity. Moreover, there remains a limited understanding of the genetic variability of A. altissima populations and their susceptibility to different genotypes of Verticillium spp. According to Díaz-Rueda et al. ([5]), various physiological, cellular, and molecular mechanisms of resistance have been proposed in V. dahliae resistant genotypes. Therefore, elucidating whether a molecular mechanism underlies the resistance or tolerance of A. altissima to Verticillium wilt should be considered a primary objective.

Our findings confirmed the rapid colonization of declining or dead tissues by various fungal species. In particular, the rapid spread of Armillaria spp. is noteworthy, as it can increase plant mortality and create stability issues in dead trees, especially along roads or in urban areas. Therefore, it is crucial to promptly remove dead trees when potential hazards are present.

The real-time PCR-based assay using the VertBT primer set showed higher sensitivity in detecting V. dahliae in different woody hosts such as maple and ash ([1]). Likewise, our results demonstrate that this method could be used to screen for the presence of this fungus in A. altissima. However, failure to detect the fungus in many samples could be due to experimental factors, such as difficulty extracting DNA from woody tissue, which can yield low levels of plant DNA and, consequently, lower concentrations of V. dahliae genomic DNA. Moreover, woody tissue often contains high concentrations of compounds that may inhibit real-time PCR reactions. These aspects should be considered to improve the sensitivity of V. dahliae detection in woody tissue using the VertBT primer set.

Despite the broad host range of V. dahliae, no symptoms have been observed on nearby trees in any of the disease foci. The pathogenicity tests confirm that the obtained isolates of V. dahliae are specifically harmful to A. altissima, corroborating previous observations reported in the literature ([22], [29]). Research on the pathogenicity of V. dahliae in different plant species (Acer platanoides, Castanea sativa, Quercus rubra, Sorbus aucuparia, and Ulmus glabra) has shown encouraging results ([18]). However, it is essential to maintain continuous field observations and perform controlled inoculations to further verify the host specificity of V. dahliae, given the significant risk it poses to many other woody hosts and agricultural crops. Moreover, the persistence of the fungus in the soil could pose an additional challenge for future vegetation, thus requiring further investigations.

The natural spread of the foci of A. altissima wilt has been impressive in the investigated region. Indeed, the disease was first observed in Italy in 2017 ([19]), but is now present in Veneto and Emilia-Romagna (G. Maresi, personal communication) and has recently been confirmed in Tuscany ([28]). In a few years, the disease has spread across northern and central Italy, becoming a significant constraint on A. altissima dispersal at all sites.

In the above context, reporting the presence and monitoring the natural spread of wilt could be a response by the Public Administration to the EU’s request to address the invasion of A. altissima. Moreover, the spread of the disease could be exacerbated by the use of selected Verticillium spp. strains as mycoherbicides ([6], [30]), which are effective though hazardous methods for introducing the pathogen into unaffected areas. However, further confirmation of the absence of collateral damage in the affected ecosystem is essential and requires specific investigation.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Karen Wells for her review of the English language in the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author Contributions

CMOL, MCF, DA, and GM contributed to the study conception and design. All the authors contributed to material preparation, data collection, and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by CMOL. GM and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Online | Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Fondazione Edmund Mach, Research and Innovation Centre, San Michele all’Adige, TN (Italy)

Daniele Andreis 0000-0002-4898-8076

Giorgio Maresi 0000-0001-6806-6135

Fondazione Edmund Mach, Technology Transfer Center, Via E. Mach 1, 38010 San Michele all’Adige, TN (Italy)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Oliveira Longa CM, Ferretti MC, Andreis D, Maresi G (2025). Natural spread of Verticillium wilt as effective constraint on Ailanthus altissima invasion. iForest 18: 391-398. - doi: 10.3832/ifor4843-018

Academic Editor

Pierluigi Paris

Paper history

Received: Mar 01, 2025

Accepted: Nov 25, 2025

First online: Dec 22, 2025

Publication Date: Dec 31, 2025

Publication Time: 0.90 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2025

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 771

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 194

Abstract Page Views: 323

PDF Downloads: 234

Citation/Reference Downloads: 1

XML Downloads: 19

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 49

Overall contacts: 771

Avg. contacts per week: 110.14

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

(No citations were found up to date. Please come back later)

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Verticillium wilt of Ailanthus altissima in Italy caused by V. dahliae: new outbreaks from Tuscany

vol. 13, pp. 238-245 (online: 19 June 2020)

Research Articles

Are Mediterranean forest ecosystems under the threat of invasive species Solanum elaeagnifolium?

vol. 14, pp. 236-241 (online: 10 May 2021)

Research Articles

Essential environmental variables to include in a stratified sampling design for a national-level invasive alien tree survey

vol. 12, pp. 418-426 (online: 01 September 2019)

Research Articles

Assessing escapes from short rotation plantations of the invasive tree species Robinia pseudoacacia L. in Mediterranean ecosystems: a study in central Italy

vol. 9, pp. 822-828 (online: 25 May 2016)

Research Articles

Scale dependency of the effects of landscape structure and stand age on species richness and aboveground biomass of tropical dry forests

vol. 16, pp. 234-242 (online: 23 August 2023)

Technical Notes

Stem-injection of herbicide for control of Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle: a practical source of power for drilling holes in stems

vol. 6, pp. 123-126 (online: 05 March 2013)

Research Articles

Fungal community of necrotic and healthy galls in chestnut trees colonized by Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae)

vol. 12, pp. 411-417 (online: 13 August 2019)

Research Articles

Seven Ulmus minor clones tolerant to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi registered as forest reproductive material in Spain

vol. 8, pp. 172-180 (online: 13 August 2014)

Research Articles

Exploring patterns, drivers and structure of plant community composition in alien Robinia pseudoacacia secondary woodlands

vol. 11, pp. 586-593 (online: 25 September 2018)

Research Articles

Emerging pests and diseases threaten Eucalyptus camaldulensis plantations in Sardinia, Italy

vol. 9, pp. 883-891 (online: 29 June 2016)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword