Problems and solutions to cork oak (Quercus suber L.) regeneration: a review

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 16, Issue 1, Pages 10-22 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor3945-015

Published: Jan 09, 2023 - Copyright © 2023 SISEF

Review Papers

Abstract

This study aimed to review the requirements and difficulties of natural and artificial regeneration of cork oak (Quercus suber L.) in the Mediterranean Basin. Cork oak regeneration is achieved naturally by means of sexual or vegetative reproduction (by seeds or by sprouting), or artificially through direct seeding, or seedling planting. Both natural and artificial regeneration of cork oak frequently encounter numerous difficulties which limit the ecological conditions for cork oak regeneration, including acorn predation, slow growth, vegetative competition, browsing of seedlings, fires, pests and diseases, and summer drought. We reviewed the state of the art of these difficulties and summarize the potential solutions for each regeneration form.

Keywords

Natural Regeneration, Artificial Regeneration, Direct Seeding, Plantation, Stump Sprouts

Introduction

Cork oak (Quercus suber L.) has a key place among the forest species of the Mediterranean Basin due to its high environmental, socioeconomic, and landscape value. Its bark (cork) is a highly valuable natural resource used in many ways ([5]), and its fruits (acorns) are important in animal feed due to its biochemical and energetic properties ([12]). Cork oak forests also support recreational and tourism activities for both local people and tourists from abroad. Cork oak is among the most western sclerophyllous oak species of the Mediterranean Basin, covering large areas both on the southern (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia) and northern (Italy, France, Spain and Portugal) Mediterranean region. It covers a total area of about 2.123.000 hectares, 67% of which is in Europe and 33% in Africa ([5]). It is adapted to the Mediterranean climate with an annual mean temperature of 13-18 °C and annual minimum rainfall of 400 mm.

The existence of relic groves far from the current limits of the main geographic range of the species, either towards the North or the South, allowed Natividade ([90]) to assume that the range of cork oak was much wider than it is at present. For several decades, cork oak area has suffered a continuous decrease due to numerous factors, such as seed predation, summer drought - causing mortality that may reach up to 100% in open areas ([91]) -, seedling requirements at the time of their establishment ([125]), slow growth ([74]), vegetative competition ([32]), anthropogenic influences (grazing and intensive forest exploitation - [94]), wildfires ([29]), pests and diseases ([31]), and lack of management or mismanagement. Our goal is to summarize the different problems that affect the natural and artificial regeneration of cork oak, while proposing possible solutions that may help foresters and land-owners to reduce these problems.

Natural regeneration

Natural regeneration consists of two different reproductive forms: sexual regeneration by seeds, and vegetative regeneration by sprouts.

Natural regeneration by seeds

Seeds play an important role in the biology of populations through the natural replacement of individuals that die and the colonization of new areas ([80]). Cork oak may start producing acorns at the age of 15-20 years ([91]). Maturation of cork oak acorns takes place either in the autumn of the flowering year (annual acorns) or in the autumn of the next year (biennial acorns - [34], [38]). The production of acorns per tree is highly variable, depending on several factors such as age, tree’s condition (healthy or diseased) and climatic conditions ([138]). Moreover, acorn production is highly variable between years ([41]), and thus regeneration is only common during years of high yields (masting). Acorn fall takes place in the autumn (October-November, or even until January - [52]). In the absence of climate (drought) and edaphic constraints, as well as predators (rodent, wild boar, livestock, etc.), acorns germinate easily ([132] - see Fig. S1 in Supplementary material).

Seedling survival is highly variable, and it is known that it rapidly decreases with time. Studying natural regeneration from seeds, Messaoudène et al. ([82]) observed that seedlings may exhibit high density, but only during the first two years after establishment; thereafter density quickly decreases because of the mortality of young seedlings, in agreement with previous results of Hasnaoui ([51]) who reported that up to two-thirds of seedlings generally die after the first five years and almost all seedlings die after ten years. Allili ([6]) and Merouani et al. ([80]) also noted that seedlings of the current year were much more numerous than those from previous years and that no seedling was found after two years. Observations in the field point to the existence of a multitude of mortality factors, some of which may have cumulative effects ([94], [54]).

Effect of climatic and orographic factors on natural regeneration of cork oak

Influence of drought and summer heat

The germination rate of a healthy cork oak acorn may exceed 90% ([78]) and even reach 100% ([55]). Thus, once fallen on the ground, an acorn that has escaped predation is likely to germinate and produce a young plant. However, during their first summer, young cork oak plants exhibit high mortality rates up to 70% ([80]). Some studies report that the highest mortality rate during this season occurs during the month of August, apparently due to high temperatures ([95] - Fig. S2 in Supplementary material). Cork oak seedling survival and growth may be severely limited by summer water deficits ([100]), which may explain high seedling mortality associated to this season ([119]). Drought and the reduced amount of water contained in the superficial soil layers, makes it harder for roots to dig into deeper soil, often causing drying up during the first summer after emergence ([94]). The progressive desiccation of upper soil layers combined with the small depth reached by the root system are the main factors causing the weakening of cork oak seedlings ([94]). In addition to rainfall scarcity during the summer period, greater solar radiation loads can also contribute to damage the leaves.

Climate change

Climate change represents a threat to cork oak forest conservation. Studies point to three potential impacts on cork oak forests ([106], [37], [101], [135]). First, reduced water availability will result in reduction in growth, increased cork oak forest decline, and reduced cork production. Second, the drier and warmer environmental conditions associated with climate change may result in increased incidence of damage due to attacks by pests and diseases, including those that affect the production and quality of cork. Third, more frequent, intense, and larger fires may occur owing to the warmer and drier weather conditions. These impacts will have negative effects on cork oak forests. One of the main actions taken by the Life+Suber project has been to characterize climate change vulnerability of cork oak forests ([88]) as a first step towards defining and quantifying risk due to climate change. Vulnerability will, however, vary according to the type of impact, the geographical location of the forest, its management history, and current condition.

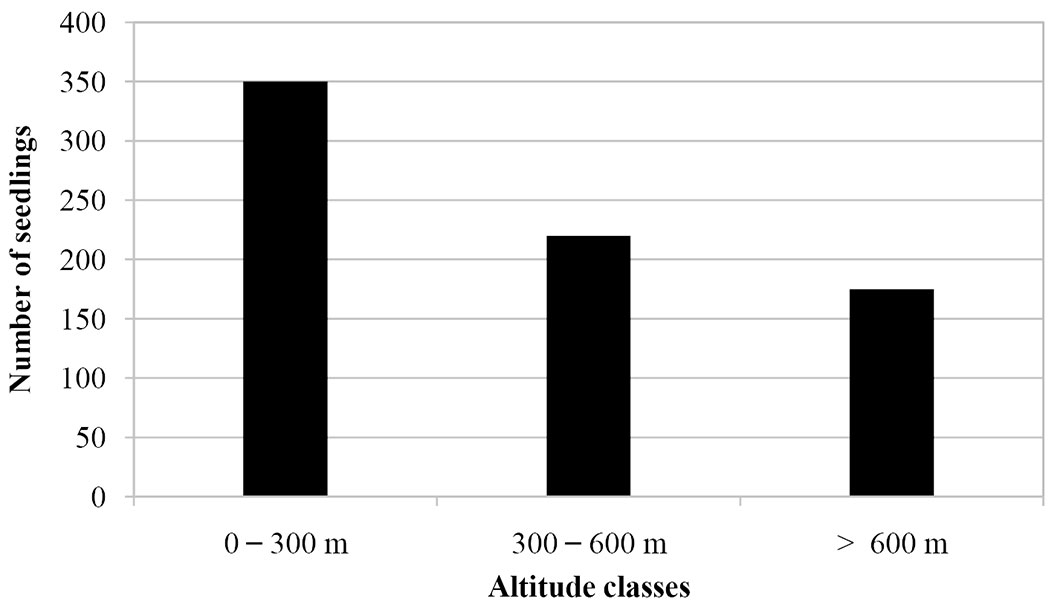

Influence of altitude

Several studies have focused on the effect of altitude on the recruitment of cork oak seedlings ([82], [95], [56]). In these studies, regeneration of cork oak seedlings was found to decrease with increasing altitude. Altitude acts on cork oak regeneration through its influence on the variation of humidity and temperature ([19]). Indeed, the higher the altitude, the higher the humidity. On the contrary, temperature decreases with increasing altitude. Cork oak is a thermophilic species ([56]), which may explain why its regeneration is mostly favored at lower altitudes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 - Effect of altitude on the distribution of natural cork oak seedlings (source: [56]).

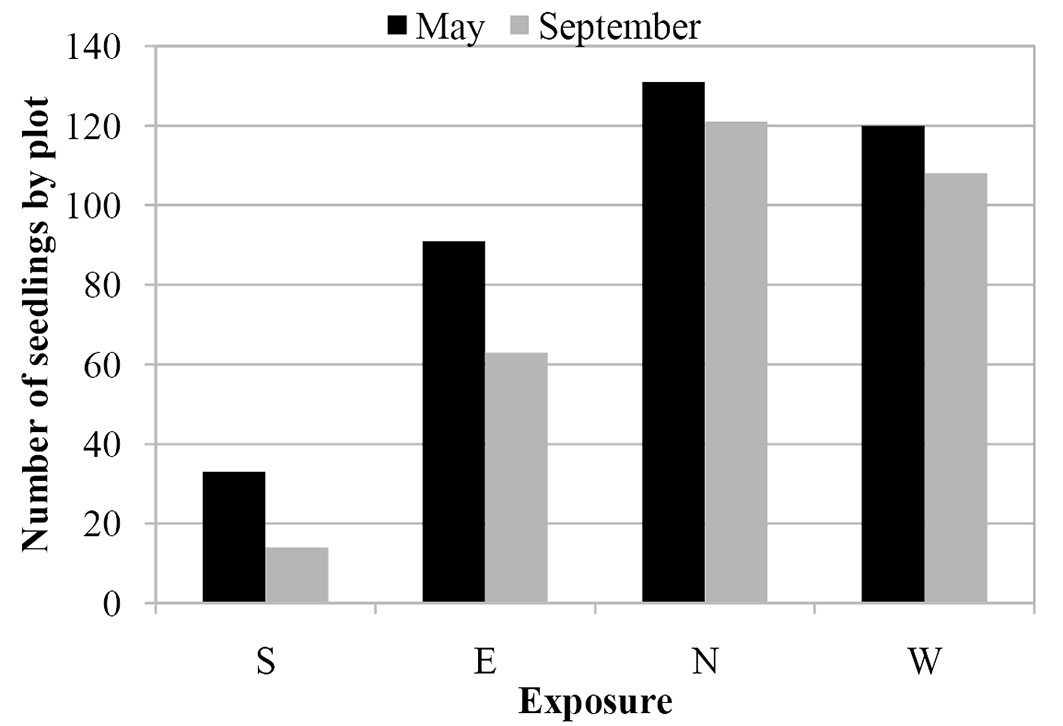

Influence of exposure

Exposure often plays a crucial role in the regeneration of cork oak. In southern exposures sunlight is stronger, light is more intense, air is drier, and both evaporation and transpiration are greater ([95]). Consequently, northern exposures are more conducive for cork oak regeneration than southern exposures ([95], [140] - Fig. 2). Khanfouci ([62]) reported that the prevailing North-West winds make northern and western exposures wetter and thereby more favorable for seedling recruitment. Exposure interacts with the local climate ([15]) to determine the distribution of natural cork oak seedlings ([95]).

Fig. 2 - Effect of exposure on the distribution of natural cork seedlings (source: [95]).

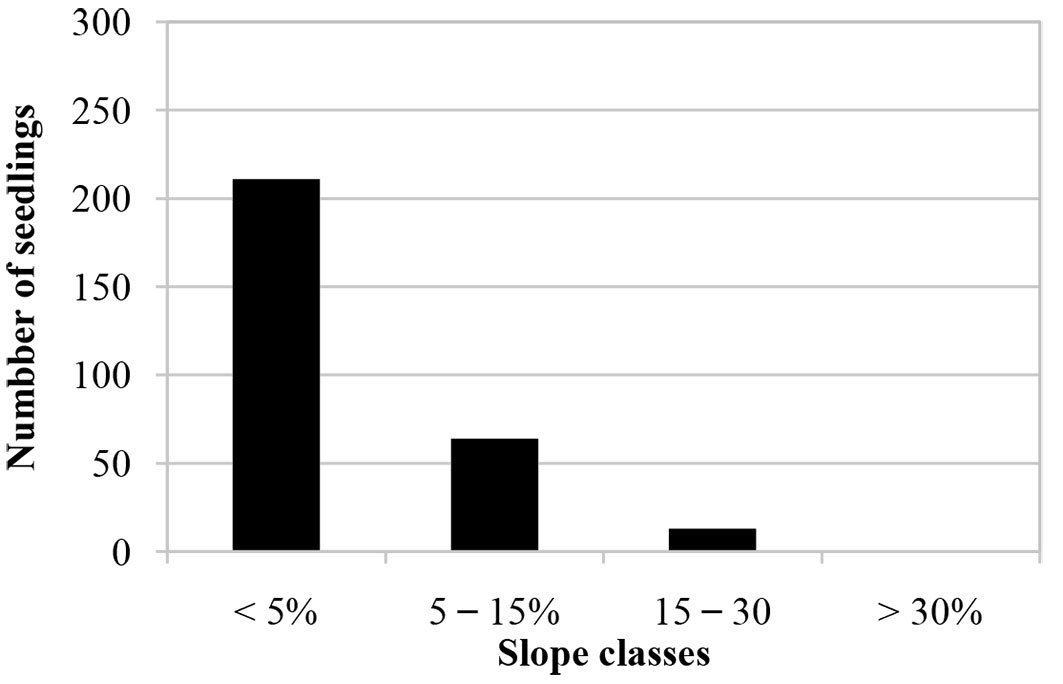

Influence of slope

Slope can also have a marked influence on the establishment and development of cork oak seedlings; usually, the lower the slope, the greater the regeneration ([95], [54]). Messaoudène et al. ([82]) noted a variation in seedlings density from 866.6 seedlings per 200 m² under a slope class of 6-9% to 336.6 seedlings per 200 m² under a slope class of 12-25%. Boussaidi et al. ([20]) also reported a decreasing number of seedlings with increasing slope, and a complete absence of cork oak seedlings in steeper slopes (>30%) (Fig. 3). According to Khanfouci ([62]), in flat areas, seedlings can develop a strong root system and are able to better resist to drought during the long dry period. Steep slopes are unfavorable for the establishment of acorns and even if they do germinate, it is difficult for them to survive because of the lack of water retention of the soil ([139]) and the lack of soil nutrients due to the effect of leaching by water runoff ([19]). In flat areas, soil is generally richer, deeper, and damper as it receives nutrients and alluvial inputs from upstream runoff ([19]). Such flat areas may receive, in addition to the acorns of their own mother trees, acorns transported by runoff ([51]). Thus, such areas are conducive to the establishment of seedlings ([95]).

Fig. 3 - Effect of slope on the distribution of natural cork oak seedlings (source: [20]).

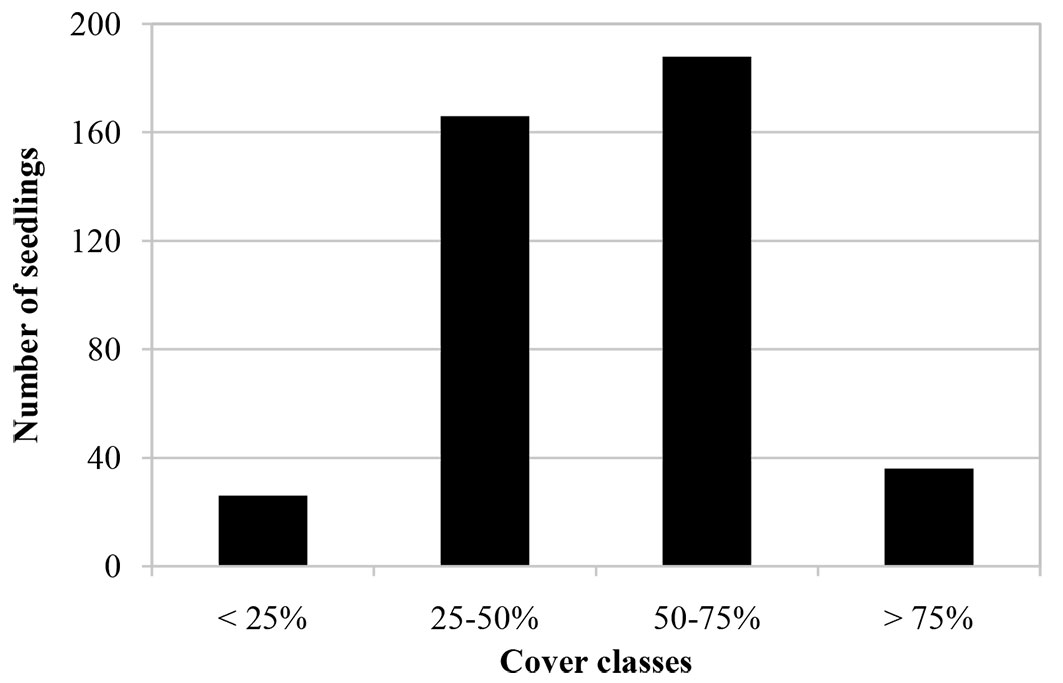

Effect of canopy cover of tree and shrub layers

The abundance of seedlings under adult cork oak trees depends on the canopy cover ([54], [20] - Fig. 4). With increasing tree cover and limitations for light, older saplings begin to exert strong competition for available light by obstructing solar radiation, thereby suppressing the growth of younger ones ([100]). Indeed, as previously reported by Messaoudène et al. ([82]) and more recently confirmed by Nsibi et al. ([95]), the number of seedlings of the current year is still much higher than those of previous years. Some authors ([82], [95]) have even reported a total absence of young cork oak seedlings under adult trees, when the canopy cover is over 75%. Cork oak is a light-demanding species especially during the seedling stage, thus, seedlings are not able to grow under the deep shade of mother trees with thick crowns ([95]). In addition, even if the seedling is successful in getting established under the canopy of an adult tree, it will grow slowly ([18]), because of the low amount of light ([57]). This highlights the unfavorable effect of dense stands on natural regeneration by seeds ([120]).

Fig. 4 - Effect of canopy cover on the distribution of natural cork oak seedlings (source: [20]).

On the other hand, under a low canopy cover, soil is subjected to the direct action of solar radiation leading to desiccation ([54]), particularly during the summer. Hence, high irradiation can amplify the negative effects of summer drought and thus the mortality risk due to other factors ([98]). Therefore, both a low and high density of cork oak adult trees may hinder seedling regeneration. Sander ([112]) confirmed that the highest survival rate was obtained under moderate canopy densities. Similarly, Nsibi et al. ([95]) observed that cork oak regeneration was favored under an intermediate cover between 50% and 75%.

The density of the shrub layer (high or low) is also a key factor that influences cork oak seedling regeneration. A high density of shrubs protects seedlings against predation ([51]) and especially against drought and summer heat by providing shading ([8]). However, high shrub density can prevent seed germination due to competition. Additionally, once germinated, seedlings do not grow well under high shrub density due to competition for light and water ([102]). According to Sander ([112]), 10% light at the ground level is insufficient for seedling survival and growth. This agrees with M’hirit ([69]) who reported that regeneration is intimately related to silvicultural factors such as cover density. By contrast, if the density of shrubs is low or shrubs are not present, germination rates are much higher, although seedling survival is nonetheless uncertain due to direct exposure to solar radiation during the summer. Mortality of cork oak seedlings varied from 78.3%-90.6% and 17.8%-33.8% in the absence and presence of shrubs, respectively ([51]).

Effect of seed predation

Seed predation is another commonly cited limiting factor for cork oak natural regeneration ([29], [8], [107]). Many agents are responsible of this predation. Livestock (e.g., cows, sheep, goats) consume large amounts of acorns below parent trees ([105]), particularly in open woodlands ([71], [100]), as dense forest ecosystems are not in general easy to be grazed by livestock. Other large wild ungulates, such as deer and wild boar, are also known to consume large amounts of acorns ([53], [27]). Various studies ([137], [45], [104]) have shown that rodents are also major predators of acorns. Vincent ([137]) reported that wild boars and rodents were responsible for 50% of the depredation of acorns. Other biotic agents like birds were identified also as potential predators affecting acorns. In autumn, jays collect healthy acorns from the tree crowns ([100]). A pair of jays may scatter and hoard several thousand acorns in a single season ([35]). Two additional birds that feed heavily on cork oak acorns are the woodpigeon (Columba palumbus) and the common crane (Grus grus), which overwinter in many Iberian and North African oak woodlands ([100]). Acorns also are a food source for insects. Small exit holes made by larvae of the acorn moth (Cydia spp., Lepidoptera) or the acorn weevil (Curculio spp., Coleoptera), are often found in acorns ([100], [121]). The proportion of acorns depredated by these insect larvae is highly variable, varying from 17% to 68% ([21]). Although many damaged acorns maintain their viability, they give rise to seedlings with reduced vigor and a lower probability to survive especially under drought stress ([100]).

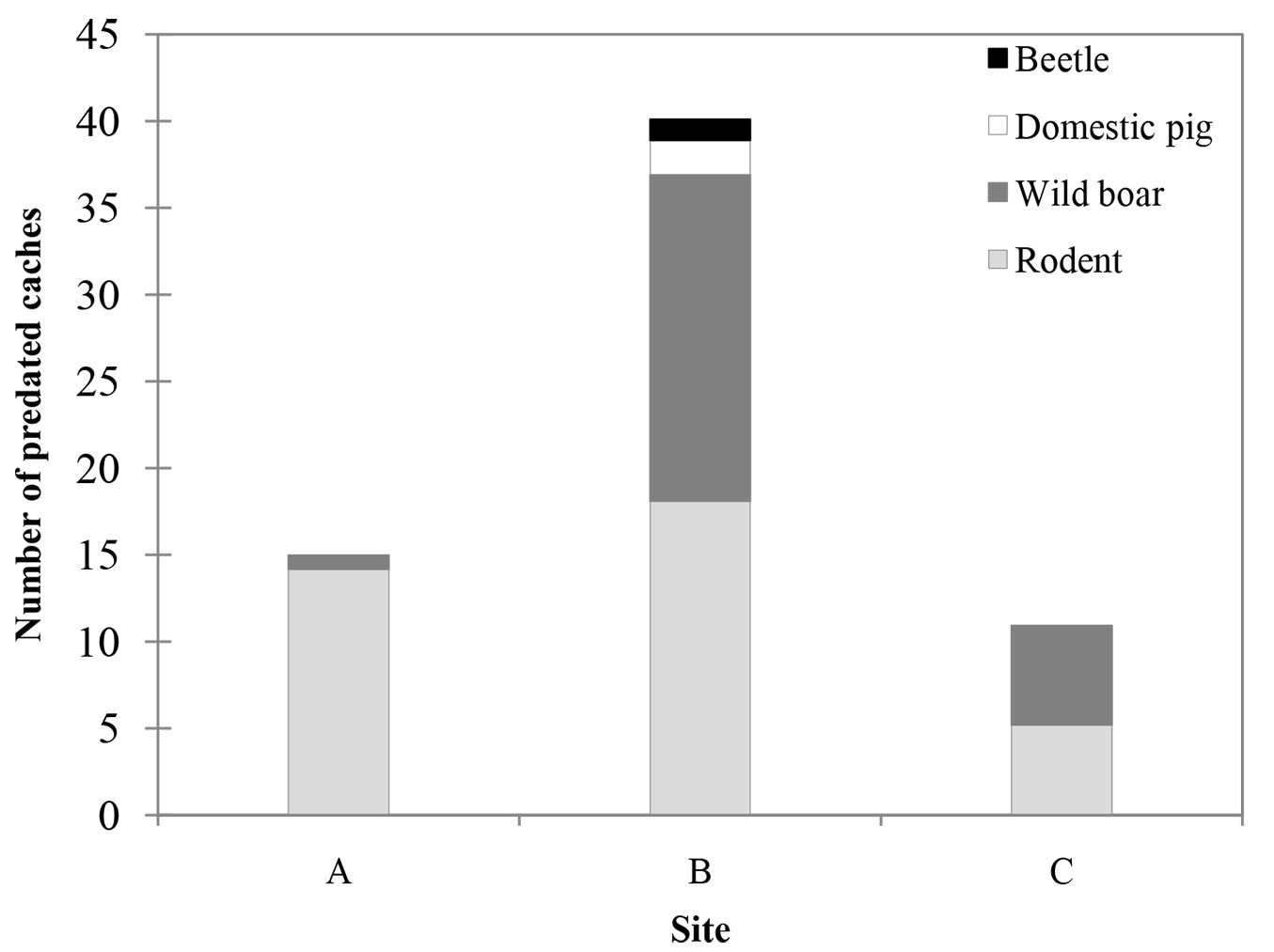

However, seed predation can be highly variable, depending on the presence and abundance of predators. For example, Arosa et al. ([8]) studied the effect of various predators on the consumption of cached acorns, concluding that predation of acorns by rodents and wild boar was higher than by domestic pigs and insects, but no other animals were considered (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 - Cache predation in three different sites according to predator type. The number of predated caches totals 300 per site (source: [8]).

Effect of fire

Fires are among the main threats to the decline of cork oak in the Mediterranean Basin ([28]). It is estimated that fires burn 700.000 to 1 million ha of Mediterranean forest each year, causing enormous ecological and economic damage ([128]). After fire, natural regeneration from seeds is much less common because in most cases acorns and flowers are destroyed by heat, and even when the crowns survive, trees will take at least 2 or 3 years to produce acorns again. In addition, seedlings may also face difficulties to establish and develop in a post-fire environment, which often present drastic changes in relation to pre-fire conditions ([29]).

FAO’s Fire management Voluntary Guidelines state that: “Fire prevention may be the most cost-effective and efficient mitigation programme an agency or community can implement” in order to preserve Mediterranean cork oak forests. Prevention should be focused on “sustainable forest management” to limit the risk of wildfires. Application of adequate forest management practices, including avoiding debarking injuries, soil erosion, and grazing pressure, enhances the resilience of cork oak forests and reduces the negative economic and ecological impacts of wildfires ([108]).

Natural regeneration by sprouting

Cork oak vegetative natural regeneration by sprouting usually occurs via basal, trunk or crown sprouts ([29]). Similar to most Mediterranean broadleaved species, cork oak has the capacity to resprout from basal buds after disturbances, when stems or crowns are severely damaged ([30]). Such severe disturbances in adult trees in the Mediterranean areas are mainly due to wildfires, while in young seedlings or saplings the causes can be more diverse, including for example herbivory. Cork oak regenerates easily from sprouts (Fig. S3 in Supplementary material), even into an advanced age. According to Franclet ([44]), cork oak can sprout until an age of 110 to 120 years under favorable conditions and 70 to 90 years elsewhere. Regeneration by sprouting requires, however, precautions to be taken when cutting mother trees; indeed, only relatively young trees should be cut ([51]). Cutting must also be made outside the period of vegetative activity to avoid stump mortality, and it is preferable that it is not systematic (a clear-cutting) but rather done in narrow strips, while keeping a light shrub layer in order to always have an adequate forest environment in terms of temperature, hygrometry, and luminosity ([51]). On the other hand, a clear-cutting can result in a reduction of genetic variability within the stand ([132]). There is very little information and literature about how to manage cork oak stump sprouts. For example, Varela ([132]) suggests that to maximize the effectiveness of this regeneration mode, wood clearance should be done when the sprouts are 5 years old and that only one or two stump sprouts should be kept (Fig. S4 in Supplementary material). Cardillo et al. ([26]) suggest that one to three of the most vigorous sprouts per stump could be retained depending on stump diameter. Early thinning is not recommended because sprout canopy helps to control excessive undesirable resprouting ([58]). Concerning herbivory by livestock or large wild ungulates, several authors suggested limiting the access of animals by fencing the area or installing individual protections to protect sprouts from browsing ([29], [108]). Sixteen years after coppicing treatments, a failure of the recovery process and cork oak survival were observed due the presence of continuous high load grazing ([118]) and the absence of protection. No stump sprouts exceeded 0.05 m in height as a result of browsing from grazing animals ([118]). Regeneration by rhizomes can also occur but is less common, particularly in adults. Regeneration by sprouting is clonal, and the individuals remain genetically identical to trees from which they are derived, which is important to be considered by managers. It has several advantages and less disadvantages, when compared to regeneration by seeds (Tab. 1).

Tab. 1 - Advantages and disadvantages of regeneration by sprouting and seeds (sources: [90], [29]).

| Pros & cons | Regeneration by sprouting | Regeneration by seeds |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | - Survival is usually higher - Growth is usually faster - Higher competitive advantage over coexisting woody plants - Well-developed root system - Better resistance to browsing and water stress - Reduction of time (i.e., 10-15 years) for production of cork compared to a tree coming from seed |

- Development of trees with higher longevity |

| Disadvantages | - Weak sprouts likely from trees with declining root systems | - Requires the existence of nearby adult trees with good masting - Seedlings usually require many years to establish and develop due to slow growth of the species - Low competition with neighboring vegetation- Acorn predation and browsing of seedlings - Sensitivity to drought, particularly during the first summers as seedlings are not yet well established - Regeneration, just after wildfires, is rare (acorns and flowers are usually destroyed) or slow because crowns require years to produce acorns again |

Artificial regeneration

Artificial regeneration is usually used either for afforestation (installation of a species on a land, prairie or heath), reforestation (reconstitution of a forest stand exploited or degraded), or as complement to natural regeneration. Afforestation of agricultural land is especially important from the point of view of soil use, the environment, and as a contributor to reducing the shortage of forestry products. Consequently, the European Communities has established aid schemes encouraging the renewal and expansion areas of forest species including cork oak, with investment in the latter reaching 1400 Euros per hectare. In artificial regeneration the plant material used comes almost entirely from seeds (direct seeding) or from seedlings (planting). In both cases, there is human intervention during the transfer and distribution of seeds or during planting. Thus, artificial regeneration is represented in two forms: regeneration by direct seeding or seedling planting.

Artificial regeneration by direct seeding

In order to produce high quality seedlings, managers should preferably select healthy acorns, not attacked by insects. Thus, it is recommended to collect acorns directly from tree branches and avoid collecting those fallen on the soil that usually suffer higher infection by insects ([55]).

Acorns should be sown as soon as possible after their collection ([111]). The highest germination rates are achieved when acorns are collected at the time they fall naturally (over 90% - [81]). Early seeding allows young plants to better cope with the summer heat. After collection, acorns are especially sensitive to drying and their ability to germinate can decrease rapidly with even small losses of moisture ([111]). For instance, a reduction of 10% in moisture content provoked a 50% drop in the germination of blue oak (Quercus douglasii - [111]). As acorns are sensitive to drying, and weather conditions when acorns drop can be hot and dry, acorns should be collected directly from tree branches ([71]). Once acorns fall to the ground, their quality declines quickly ([111]). Collected from trees, acorn ripeness can be predicted through color, which turns brown when ripe, or the ease of dislodging acorn from the cupule or cap. Fruits fall from October to January, but the first acorns to fall are often empty and parasitized ([52]). If acorns must be collected from the soil, it is desirable to choose mature, healthy, smooth and derived from the second fructification (November, December - [52]). Insect-infested acorns, germinated acorns with broken radicles, and dry acorns should be rejected. Some parasites, specially the larvae of weevils (Curculio) and moths (Cydia), may be present inside the acorn ([111]), but infested acorns can be eliminated by float-testing in water ([78]). In fact, infected acorns can also be collected and seeded on condition that they treated with insecticides. For example, the halofenozide RH-0345 used at high-dose (200 mg L-1) against Cydia spp. and Curculio spp. was found to be effective against these insects, resulting in higher germination rates compared to an untreated control ([1]).

Direct seeding allows cork oak seedlings to quickly develop a taproot, which can rapidly explore deeper layers of the soil. In addition, direct seeding avoids the transplanting shock of plants cultivated in the nursery, and the reduction of root development characteristic of containerized seedlings ([33]). Direct seeding requires, however, a large number of acorns, which depends on the highly variable annual acorn production (masting behavior). Conservation and storage of acorns are therefore necessary due to masting. Acorns should be stored at cool temperature, between -1 °C and -3 °C but not below -5 °C, and kept under controlled conditions, at 40%-45% humidity, in containers with adequate ventilation ([111]). When acorns are stored properly, they can maintain their germination capacity, at least, for up to 21 months ([14]).

In order to improve acorn emergence and accelerate the germination, it is recommended to immerse acorns in water with fungicide for 24 hours before seeding ([132]). However, the majority of regeneration problems by direct seeding is acorn predation. Sown acorns are easily spotted by different predators (rodents, cattle, wild boar, etc.) and therefore are readily destroyed ([19]). Torres ([126]), Cañellas et al. ([25]) and more recently Moreno et al. ([86]) suggested coating seeds with repellents to reduce rodent depredation. Covering seed lines with branches may also help to reduce acorns predation by rodents or some birds (e.g. crows - [141]). Sardin ([114]) and Leverkus et al. ([67]) recommended protecting individually the acorns with metal grills or “acorn shelter”, as well as seeding more than one acorn per hole. If neither physical protection nor repellents can be applied, two acorns can be sown at the same time, but at two different depths; if the first acorn is eaten, the second is likely to be spared as depredation decreases with increasing acorn planting depth ([124]). In general, acorns should be sown at 1 to 3 cm deep. However, it may be better to sow them even deeper if rodents are present because they could dig them up ([111]). Some authors ([36], [68]) reported that sowing in the spring pre-germinated acorns picked up on the soil at the end of the winter may appear as a solution against acorns predation. Other authors ([66]) reported that in environments undergoing high rodent predatory activity, early sowing of acorns during the seeding season (period of acorn-eaters satiation) is advised in order to maximize the success of tree regeneration. It is recommended to bury the acorn, not only to avoid predation, but also to prevent it from drying, thus facilitating germination. Indeed, it has been shown that a superficial seeding (not buried) yields very low success rate (less than 1% - [120]). When the area to regenerate by seeding is frequented by livestock or wild boar, this will constitute a danger both for the acorn and the future plant (the wild boar can pull off the young plant looking for the acorn). Fencing the sown plots, until the seedlings are well established, may be a solution. To facilitate better success of direct seeding, the germinative power of seeds should be quite high and the level of competition with the other species present should be low ([3]).

Traditional techniques for direct seeding are broadcasting, dibbling and drilling ([139]). However, drilling is the most recommended technique ([141]), in which 1-2 acorns are sown every 5 m along the furrow opened by the ripper, for a density of 1000 acorns ha-1 ([111]). Sowing more acorns in the furrows reduces the risk of failure due to seed predation, but entails culling before seedlings are 3-years old when all the acorns germinate ([111]). Nevertheless, high densities have the advantage of allowing the removal of weak or poorly shaped trees, increasing stand quality ([84]).

Germination of cork oak acorns is high and does not present a problem ([78]). It should be recalled, however, that the total elimination of shrubs in order to reduce competition is not recommended because young seedlings need to be partially shaded during their first years ([19]). Furthermore, shrub suppression increases soil erosion ([96]) and can negatively impact the regeneration of cork oak seedlings and saplings. Indeed, some authors ([9]) consider that the main limitations to the lack of cork oak regeneration rise from land management practices (e.g., shrub suppression), rather than environmental factors.

Artificial regeneration by planting

Seedling production

In addition to genetic quality, the plant production stage is key in producing high morpho-physiological quality seedlings capable of coping with transplant shock, establishing and growing in reforestation sites, and withstanding abiotic stress ([64]). Qualification standards for seedlings of cork oak vary among and even within countries (Tab. 2). In Morocco, for example, qualification standards for seedlings vary among regions depending on their ecological characteristics ([17]). For non-EU countries, qualification standards for seedlings are primarily based on morphological criteria (i.e., height and diameter).

Tab. 2 - Qualification standards for seedlings of cork oak species. Examples given for Tunisia, Morocco (region of Bab Azhar) and Spain (sources: [64], [4], [132]). (nd): not determined.

| Criteria | Parameter | Tunisia | Morocco | Spain | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Min | Max | Min | Max | ||

| Morphological criteria | Height (H, cm) | 28 | 40 | 20 | 50 | 23.81 | 66.77 |

| Root collar diameter (D, mm) | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3.10 | 4.61 | |

| Ratio (H/D) | <8 | <8 | nd | nd | nd | nd | |

| Dry weight of above-ground biomass (DWAB, g) | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.51 | 6.17 | |

| Dry weight of below-ground biomass (DWBB, g) | nd | nd | nd | nd | 4.90 | 7.92 | |

| Morphological indications | DWAB/DWBB | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.43 | 0.76 |

| Physiological criteria | N (%) | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.20 | 1.27 |

| P (%) | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.07 | 0.15 | |

| K (%) | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.41 | 0.45 | |

| Ca (%) | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.19 | 0.22 | |

| Mg (%) | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.35 | 0.64 | |

Cork oak plants can be produced either from seed (acorns) or vegetatively (cuttings - fragments of stems or roots -, grafting and micropropagation). The production of high-quality seedlings, however, requires that the culture conditions in the nursery or laboratory are carefully controlled. Consequently, seedling production in the nursery from acorns is the most commonly used technique. In addition, cork oak acorns exhibit high germination capacity when healthy and mature seeds are used ([78]). Seeds, which are the result of sexual reproduction, are the foremost source of genetic variability, thus allowing plant species to cope with unpredictable environmental conditions ([39]). However, one issue related to cork oak seedling production from seeds is the masting habit that characterizes this species. This problem can be overcome with proper storage of acorns. In non-mast years, both acorn production and genetic diversity are reduced. Consequently, reproductive material collected during these years should be avoided ([40]). Cork oak enumerates biotypes with annual and biennial acorn maturation, which may be considered as two ecological strategy types resulting from species adaptation to a Mediterranean climate. The annual biotope maintains the characteristics of the primitive type (slow type), with a reduction of the period of dormancy, adapted to areas with subhumid Mediterranean climates that have less contrast between seasons, whereas the biennial biotype is the response of the species to harsh climatic conditions; it is able to colonize those environments in which the annual biotope is unable to adapt ([38]). Corti ([34]) interpreted the phenomenon as an adaptive mechanism to the seasonality of the current climate compared to the uniformity of the geological period of species formation. It is important, however, to note that the same tree can bear annual and biennial fruit simultaneously, with varying ratios depending on the seasonal weather ([34]). Given the large variation observed for cork oak growth and survival in provenance trials ([133]), more attention should be paid to seed provenances. Thus, use of seed lots from locally adapted stands is advantageous from the standpoint of genetic conservation. Use of non-local reproductive material may possibly be acceptable, but on condition that the requirement of ecological similarities is fulfilled and there is no local material ([46]). The size of seedling containers is also important. A container volume of at least 400 cm3 is recommended ([134]).

Vegetative propagation is another important tool used to propagate clones of a particularly favorable genotype. This is an advantage when implementing multi-varietal forestry with high quality cork trees that have high resistance to aridity, or to conserve marginal populations and monumental trees. The first studies in cork oak, based on vegetative propagation, were cited by Natividade ([92]). Another study on cuttings was done in Morocco by Platteborze ([103]). More recently, the results of cork oak cuttings using stem ([87], [115] - Fig. S5a,b in Supplementary material) or root ([93] - Fig. S5c) fragments have shown that cork oak grows easily when cuttings are removed from young seedlings. Mtarji & Marien ([87]) reported that results are encouraging also with regard to rhizogenesis and the quality of neoformed roots. Actually, different key factors can influence the rooting of cuttings and the success rate of cuttings, including the age and physiological state of the mother tree, the cuttings collection period, the cuttings position on the mother tree, culture techniques, and the period when cuttings are done ([93], [115]). For instance, the rooting of cuttings decreases as the age of the mother tree increases ([93], [115]). On the other hand, rhizogenesis is more successful when stem fragments are taken close to the tree root system ([115]). In the Mediterranean region, the most favorable time for successful cuttings is before or just after budburst, usually February to April ([115]). This generally coincides with the spring season and with the period of active growth of new shoots.

Although the practice of grafting is a technique that dates back to antiquity and consists of combining multiple plants, its application in forestry is relatively recent ([116]). In cork oak, grafting from trees selected for their cork has been successful. The advantages of grafting are numerous: (i) it can buffer the effect unfavorable edaphic conditions both physically and physiologically thanks to the addition of the adapted root system of the rootstock and resistance to biotic and abiotic environmental stresses; (ii) by stimulating the organogenic ability of certain individuals considered inadequate for vegetative reproduction; for example, grafting of twigs coming from elderly trees on young and vigorous rootstocks favors rejuvenation; (iii) it can modify a cultivar or a variety to reach an intended objective ([116]). As a calcifuge species, grafting cork oak on other oak species that are indifferent to the chemical composition of the substrate can solve cork oak developmental problems on calcareous soils ([11]). Many conditions are, however, necessary for the success of grafting, the most important being the compatibility and affinity between the graft and the rootstock, the degree of contact between the generating zones, the condition of the graft and rootstock, and the grafting period ([116]).

In vitro culture or micropropagation is another method of vegetative propagation, consisting of the production of plants using different types of tissue fragments such as meristem, apex, axillary buds, nodes or internodes ([99], [59], [60]). Results are dependent on the composition of the growing media, which plays a main role in the process of organogenesis ([22]). Some growing media stimulate in vitro developmental processes, while others have little influence on budburst ([123], [109], [110], [49], [22]). Kbiach et al. ([59]) tested a variety of different macronutrient formulas, concluding that WPM ([70]) macroelements provided a good establishment media and propagation in vitro of cork oak from seedling stem nodes. The production of cork oak plants using vegetative propagation not only allows the production of plants with desired genetic characteristics, but also may solve the problem of cork oak masting habit.

Seedling planting

Owing to potential damage by rodents and other wildlife and the interventions required for direct seeding, many cork oak managers or owners often plant seedlings ([40]). However, successful cork oak plantations are hard to establish due to factors including slow growth, competition, animal damage ([32]), and water stress. Keys factors for successful initial establishment of seedlings of forest species in general and cork oak in particular include: planting on appropriate sites (cork oak is a calcifuge species and should not be planted on calcareous soils); obtaining good-quality seedlings; planting date; ensuring good pre-planting care of seedlings; using proper planting procedures ([61]); and the maintenance of plants during and after planting (e.g., irrigation of plants, management of competing vegetation, protection against herbivores).

Cork oak plantations are generally established with 10-12-month-old plants produced in nursery containers. However, the vigor and success rate of 6-month-old plants may be greater than that of one-year-old seedlings ([122]), reducing the production time of seedlings. Planting date may influence seedling performance ([111]), and late planting may consequently reduce chances for subsequent successful field growth. Optimal timing of planting extends from late fall ([111]) until early spring (March - [122]). Planting at this time allows seedlings to develop well-established root systems as the soil is still cool and moist ([111]). Planting after March can result in poor establishment ([122]), since soil generally becomes too dry. In general, fall is the preferred season for planting, when seedlings can benefit from subsequent rains that fix the soil around the roots and create conducive conditions for the root system ([24]).

Planting, especially when poorly done, triggers a physiological shock that must be minimized ([132]). Recently, a new planting technique has been tested for cork oak. Contrary to the classical method where the cork oak plant is buried up to the level of its root collar, in the new technique, the plant is buried up to a few centimeters above its root collar so that part of the leaves is also buried. However, it is not necessary to bury more than half of the aerial part of the plant ([134]). This “deep” planting (i) allows the plant to better take advantage of moisture deeper in the soil, (ii) isolates roots below the unfavorable conditions of drying, (iii) facilitates adventitious rooting on dormant, buried buds increasing the overall volume of the root system and improving the nutrition capabilities of the seedling ([134]). This planting technique has resulted in favorable growth results for cork oak seedlings and its implementation costs only a few additional pickaxe blows compared to classical planting, and is thus highly recommended ([134]). Initial density should be around 625 plants ha-1 ([83]), which corresponds to a spacing of 4 × 4 m. The disadvantage associated with wide spacing (5 × 6 m or 6 × 6 m) is that large poorly stocked areas may result if adjacent seedlings die ([111]). Irrigating young plants during the first year and sometimes during the second year, especially in low rainfall years, is the best solution to relieve water stress.

Generally speaking, artificial regeneration can increase genetic diversity ([63]). Adaptive forestry aims to facilitate the emergence of new genetic combinations and to facilitate the spread of the best-adapted genotypes, as well as to secure the conservation of genetic diversity to enable long-term selection ([65]). For regeneration and sustainable genetic variability, the following requirements for the use of reproductive material must be observed ([115], [40]): (i) varied and representative local material of the genetic pool; (ii) preference given for local material, which usually guarantees retention of the evolutionary and adaptive characteristics that have developed at a given site; non-local material may lead to serious failures at any stage of the long lifespan of cork oak; (iii) in the absence of local material or if there are signs of inbreeding, then restoration may rely on the introduction of material from external sources; material from localities sharing the site conditions with the regeneration site are preferred; (iv) at least 50 acorn bearing and unrelated mother trees, separated by at least 20 m, are required to maintain genetic variation at a satisfactory level within a population.

Maintenance of the plantation

Competing vegetation

One of the main causes of forest plantation failure, including for cork oak, is the absence or irregularity of maintaining vegetative competition ([129]). Competition acts to impair cork oak development through several mechanisms including water and minerals from the soil, light, and space. Controlling competing vegetation until seedling establishment (4 to 5 years) is a requirement to assure homogeneous growth of seedlings ([2]). When competing vegetation is not managed, it can severely reduce survival and/or plant growth ([89]). Methods commonly used to control competing vegetation are manual, mechanical, and chemical ([79]).

Weed control using mulching is used not only due to its effectiveness but also for its ability to provide conducive microclimatic conditions (increase of temperature and soil moisture) around mulched seedlings, while improving soil structural stability and nutrient availability ([130]). Such mulching may improve early survival and plant growth in forest plantations. Mulching benefits depend, however, on the amount of competing vegetation, genotype, site fertility ([48]), and nature of the mulch ([130]). Mulching is more beneficial on poor quality soils, under greater competing vegetation and in poor site conditions ([48]). To be effective, mulching should be applied around each plant, at a minimal surface area of 1 m² ([73]) after clearing the surrounding vegetation. Mulching can, however, be applied throughout the planting line to a width of 1 m. Mulching costs depend on the mulch type used ([79]). However, weed control using mulching is generally less costly compared to traditional techniques (manual, mechanical, chemical) due to the reduction of maintenance activities after plantation ([79]).

Despite positive results obtained with localized and walking tillage using mulching ([129]), this planting technique has been criticized for the use of synthetic products. The challenge is therefore to find a balance between the environmental impact of this technique and its efficiency. We particularly encourage the use of organic, biodegradable mulches over inorganic, synthetic ones because of their environmental friendliness ([131]). Over the last two decades, biodegradable mulches of wood, cork or agricultural fibers (linen, hemp, sisal, coconut) have gained popularity for being environmentally friendly and increasing in quality ([129]). Much more recent products, called “biodegradable plastics” or “bioplastics” are gradually appearing in the European market ([131]). They are made of materials of natural origin (polysaccharides, proteins, etc.) or derived from biotechnology (fermentation by bacteria); others are new polymers obtained by industrial synthesis ([43]). These long-lasting biodegradable mulches have similar or superior qualities to synthetic products in terms of biological efficiency on the survival and growth of trees ([131]).

Fighting animal damage

Animal damage constitutes another common obstacle for successful cork oak plantations. When herbivores are present and there is no protection, oak seedlings can be almost completely defoliated ([100]). Although they can resprout several times, overgrazing often leads to mortality ([100]). Even if they survive, browsed seedlings exhibit very slow growth ([73]). Protection of new plantations from animal damage may therefore be effective in improving seedling establishment ([85]). Protection should last until trees surpass the critical browsing height and animals are no longer a threat ([132] - (Fig. S6 in Supplementary material).

The difficulty of obtaining a satisfactory regeneration in the presence of uncontrolled herbivores ([50]) has forced farmers who practice silvopastoralism (association of trees and farming on the same parcel) or foresters who plant land frequented by a high density of herbivores to test various types of protection. Fighting against animal damage is traditionally done using fences or chemical products (oils, tar of bone, extracted from animals, odorants) acting as a repellent at the level of smell, taste or touch of animals ([10]). More recently, tree shelters have been designed to shield newly planted seedlings from animal damage. Tree shelters have proven particularly effective against animal damage ([77]), and are easy to install. However, their effectiveness depends on height, which is regulated in turn on the size of the animal threatening young plant. Thus, 1.2-m tall tree shelters are not very useful in protecting seedlings from goats and large animals (deer, cattle), while tree shelters of 1.8-m height ([73]) or more (2.1 and 2.5 m - [42]) are effective. Other shorter types of tree shelters of 60-70 cm are specifically designed for protection against rodents (rabbits, hares - [111]). The benefit offered by tree shelters is that they not only shield plants from a variety of animals, but also stimulate aboveground growth by increasing temperature, CO2 concentrations, and humidity ([127]). Many types of tree shelters are available for this purpose ([13], [97]). The use of vented tree shelters is advisable to avoid excessive temperatures, decrease transpiration rate, and keep CO2 concentrations near atmospheric values ([16]). Although their use is costly, in particular when used at large scale, these devices may allow livestock to graze after planting with less risk to the plants ([77]), benefits that are not provided by other techniques for controlling animal damage ([76]). In particular, fencing is cheaper but may be relatively ineffective ([77]) especially without frequent maintenance ([75]). Chemical substances used as repellents must be deposited in the plant, either before planting through soaking or by painting or spraying after planting. This type of protection is inexpensive, but only effective when the presence of herbivores is low ([7]). Moreover, it is not effective against browsing occurring during summer or by deer ([7]). Electric fence is a known tool for keeping farm animals enclosed while grazing ([72]) and has shown promising results regarding preventing wild boar from entering fields ([113]). However, the use of electric fences was not suitable with regard to, among other things, high building and maintenance costs ([136]).

Conclusion

With natural regeneration by seeds, cork oak acorn germination does not constitute an obstacle, assuming acorns are healthy. Several biotic and abiotic factors, however, including predation, competition, and drought may directly or indirectly inhibit seedling recruitment and cause failure of natural regeneration from seeds. In closed cork forests when shrubs are abundant, interventions from above (at the level of tree layer) and below (at the level of shrub layer) are required to promote seedling recruitment by reducing competition. In open cork oak forests, natural regeneration of cork oak from seeds is mainly hindered by livestock overgrazing ([23]). Fencing livestock for at least 15 years may help to overcome this hindrance.

Regeneration by stump sprouts can play a crucial role in safeguarding cork oak groves ([139]), as cork oaks sprout vigorously from stumps. This must, however, be done correctly (e.g., cutting of relatively young trees, outside the period of vegetative activity and only one to three of the most vigorous stump sprouts should be kept). On the other hand, it is necessary to exclude herbivores after the cutting for a period of five to ten years. When natural regeneration is inadequate to achieve the objectives (in terms of the desired tree density), reforestation by direct seeding or planting is an alternative.

Regarding artificial regeneration by direct seeding, managers should choose morphologically and physiologically ripe acorns, which generally exhibit high germinations rates (over 90%) if sown after they are harvested. Before sowing, acorns can be submerged in water and floating acorns discarded. Germination rates remain high if not held for over a month. Acorns can maintain their viability for longer when they are properly stored ([3]). Acorn size has a positive influence on germination rate and seedling growth ([78]). Thus, small acorns are usually discarded for seedling cultivation because they reduce plant quality ([117]). This, however, can potentially reduce genetic diversity of plantations. To overcome this problem, nursery fertilization may compensate for the low quality of small-acorn seedlings ([117]). To improve success of direct seeding, it is important to protect acorns (use of repellents, individual protection of acorns with metal grilles) as soon as they are sown.

Finally, cork oak may be artificially regenerated by planting. Plantations are a good option if they are done properly (high quality plant material, good soil preparation, plant maintenance (control of vegetative competition and browsing of plants by herbivorous animals), watering during the first year, sometimes in the second year if rainfall is scarce and badly distributed. If planting is done poorly, however, the project could be an expensive failure ([61]).

Direct seeding with acorns and planting of young seedlings each have advantages and disadvantages. Advantages of direct seeding include simplicity, low cost, ease of transportation to the field, production of more plants per hectare, allowing potential to select the most vigorous seedlings and minimize transplanting shock. Advantages of planting seedlings over direct seeding include avoiding acorn predation and lower initial planting density, which reduces the costs of subsequent silvicultural treatments such as thinning and necessitates fewer acorns for growing seedlings in the nursery compared to direct seeding the field. Comparison between direct seeding and seedling planting showed that both can be similarly effective when appropriate nursery cultivation conditions are adopted and seeds are shielded from predators ([47]).

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Walt Koenig (Hastings Reservation, UC Berkeley) for technical language editing. The authors also acknowledge the Faculty of Science of Bizerte (University of Carthage, Tunisia) and the Silvo-Pastoral Institute of Tabarka (University of Jendouba, Jendouba, Tunisia).

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Laboratoire des Ressources Sylvo-Pastorales de Tabarka, Tabarka (Tunisie)

Forest Dynamics and Management, INIA-CIFOR, Crtra Coruña, Km 7.5, 28040 Madrid (Spain)

Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, Purdue University, 715 West State Street, West Lafayette, IN 47907 (USA)

Centre for Applied Ecology/Research Network in Biodiversity and Evolutionary Biology - CEABN/InBIO, School of Agriculture, University of Lisbon - ISA, UL, Tapada da Ajuda 1349-017 Lisboa (Portugal)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Mechergui T, Pardos M, Boussaidi N, Jacobs DF, Catry FX (2023). Problems and solutions to cork oak (Quercus suber L.) regeneration: a review. iForest 16: 10-22. - doi: 10.3832/ifor3945-015

Academic Editor

Gianfranco Minotta

Paper history

Received: Aug 07, 2021

Accepted: Oct 24, 2022

First online: Jan 09, 2023

Publication Date: Feb 28, 2023

Publication Time: 2.57 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2023

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 37844

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 29157

Abstract Page Views: 5207

PDF Downloads: 2975

Citation/Reference Downloads: 18

XML Downloads: 487

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 1145

Overall contacts: 37844

Avg. contacts per week: 231.36

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2023): 7

Average cites per year: 2.33

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Methods for predicting Sitka spruce natural regeneration presence and density in the UK

vol. 12, pp. 279-288 (online: 23 May 2019)

Research Articles

Modelling natural regeneration of Oak in Saxony, Germany: identifying factors influencing the occurrence and density of regeneration

vol. 16, pp. 47-52 (online: 16 February 2023)

Research Articles

Short- and long-term natural regeneration after windthrow disturbances in Norway spruce forests in Bulgaria

vol. 11, pp. 675-684 (online: 23 October 2018)

Research Articles

Natural regeneration and species diversification after seed-tree method cutting in a maritime pine reforestation

vol. 15, pp. 500-508 (online: 14 December 2022)

Research Articles

Optimizing silviculture in mixed uneven-aged forests to increase the recruitment of browse-sensitive tree species without intervening in ungulate population

vol. 11, pp. 227-236 (online: 12 March 2018)

Research Articles

Long-term dynamics of stand structure and regeneration in high-stocked selection fir-beech forest stand: Croatian Dinarides case study

vol. 14, pp. 383-392 (online: 24 August 2021)

Research Articles

Shrub facilitation of Quercus ilex and Quercus pubescens regeneration in a wooded pasture in central Sardinia (Italy)

vol. 3, pp. 16-22 (online: 22 January 2010)

Research Articles

Oak sprouts grow better than seedlings under drought stress

vol. 9, pp. 529-535 (online: 17 March 2016)

Research Articles

Optimum light transmittance for seed germination and early seedling recruitment of Pinus koraiensis: implications for natural regeneration

vol. 8, pp. 853-859 (online: 22 May 2015)

Research Articles

The impact of seed predation and browsing on natural sessile oak regeneration under different light conditions in an over-aged coppice stand

vol. 9, pp. 569-576 (online: 04 April 2016)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword