Life cycle assessment of tannin extraction from spruce bark

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 10, Issue 5, Pages 807-814 (2017)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor2342-010

Published: Sep 25, 2017 - Copyright © 2017 SISEF

Research Articles

Collection/Special Issue: COST action FP1407

Understanding wood modification through an integrated scientific and environmental impact approach

Guest Editors: Giacomo Goli, Andreja Kutnar, Dennis Jones, Dick Sandberg

Abstract

Tannins have shown antifungal effects and have been considered a potential natural compound for wood preservation. Extracts produced from softwood bark contain both tannins and non-tannin compounds, which may reduce the effectiveness of tannin used as a wood preservative. The purpose of this research is to study the environmental impact of hot water extraction, identify the hot spots within the tannin cradle-to-gate life cycle and give suggestions to optimize its environmental profile. Different extraction and post-extraction scenarios of tannin production are compared using the life-cycle assessment method. Experiments were designed to study the tannin yield under different extraction scenarios; the post-extraction scenario analysis was based on literature review. The results show that the extract drying process is the primary contributor to the environmental impact of tannin production. Both preliminary cold water extraction and ultrafiltration after extraction are beneficial as they have fewer non-tannin compounds in the final products; however, preliminary cold water extraction had a considerably lower environmental performance. Successive extractions using fresh water at each cycle increased the total tannin yield, but increased the environmental burden. Using only evaporation to obtain a desired tannin concentration is not environmentally efficient. This paper provides a quantified environmental analysis for the development of tannin-treated wood products and discusses the different tannin extraction scenarios from an environmental point of view.

Keywords

LCA, Tannin, Spruce Bark, Hot Water Extraction, Evaporation, Spray Drying, Ultrafiltration, Preservative

Introduction

Preservation of wood using antifungal agents usually results in increased environmental impact ([38]) due to the preservatives or the preservation technology, and absolute impact quantities should always be related to a resultant improvement in the service life of the treated wood products. Life-cycle assessment (LCA) is an internationally standardized method ([12]) to quantify the environmental impact throughout the life cycle of the wood product. LCA also can be used to compare products with similar intended uses or to show possible improvement in the environmental performance of new products or processes.

To some extent, recent wood preservation research focused on the exploration of bio-based chemicals, e.g., condensed tannin ([31], [32], [29]) or stilbenes ([17]), with presumably lower environmental burden than traditional wood preservatives, e.g., copper or borate preservatives. The use of tannin was developed primarily in the leather and wood adhesives industries ([21]), where they are commercialized. Similar developments are foreseen for utilization of phenolic wood residue in biocomposites manufacture ([36]).

Tannins are a versatile group of polymeric phenolic compounds resulting from the plant’s secondary metabolism. In trees, tannins provide protection from herbivore, insect, fungi and bacteria attacks ([19], [1]). This protective function causes diminished efficiency for the enzymatic attack of fungi, bacteria and the digestive system of larger animals ([10]). Tannins are divided into two main classes: condensed tannins, which are oligomers made of flavanol units; and hydrolysable tannins, which are polygalloyl esters of glucose. While hydrolysable tannins are mainly extracted from chestnuts, myrabolans and oak heartwood, the current industrial sources of condensed tannins are mostly limited to mimosa bark (Acacia mearnsii De Wild.) and the quebracho heartwood (Schinopsis balansae Engl. - [21]). The bark of European softwood species is also considered to be a suitable source of condensed tannins ([4]).

The advantages of extracting tannins from bark are obvious: abundancy and availability of bark, possibility of simple hot-water extraction processes without chemicals ([15]) and the commercial value of extraction residue (bark) for bioenergy or as an organic fertilizer ([8]). Turner & Ibáñez ([34]) have shown that pressurized hot water extraction (PHWE) is an environmentally benign and promising extraction method in pilot-scale operations. However, the process of drying extracts removes some of its environmental advantages ([24]).

The use of condensed tannins extracted from European softwood is currently a niche market and product solution. One obvious drawback is the high amount of co-extracted non-tannin compounds, particularly carbohydrates (e.g., monosaccharides, oligosaccharides and pectin - [4]). As reported by Anttila et al. ([1]), the impurity of the extracts may act in opposition to the tannins’ efficiency against fungal growth, providing easily accessible mono- and oligomeric sugars for fungi and thus enabling their growth on treated material. In addition, a significant volume of carbohydrates can increase the viscosity of tannin solutions, which decrease the penetration efficacy of the wood cells ([21], [31], [33]).

Bianchi et al. ([5]) have proposed a way to increase the tannin concentration in softwood bark extracts relative to other compounds by inserting a cold-water extraction step before the hot water extractions. They found that phenolic monomers, mono- and oligosaccharides can be almost completely removed during the cold-water extraction. Although a fraction of the extractable condensed tannins is lost in the preliminary cold water extraction, the extracts from the following hot water step show a higher concentration of tannins than those obtained through a single-step, hot water extraction. Another way to purify tannins is to apply different membrane filtration methods commonly used to separate desirable compounds from a compounds mixture with a low energy requirement ([18]). In fact, Pinto et al. ([20]) reported that ultrafiltration can increase the concentration of tannins in the extracts of Tasmanian bluegum bark (Eucalyptus globulus Labill.) by about 20 to 30 per cent. This is partly because monosaccharides and other monomers, as well as smaller sized molecules, can pass through the membranes.

This paper aims to compare the environmental impact of alternative extractions and post-extraction tannin processes from the Norway spruce (Picea abies Karst.) bark using results from both laboratory and pilot-scale experiments and related previous research. It analyses two approaches to reducing the amount of co-extracts: (a) the introduction of a preliminary cold water step in the extraction process ([5]); and (b) the use of membrane filtration for separation of the tannin from the non-tannin compounds ([18]). The information provided can help optimize the industrial production procedures and forecast their environmental performance.

Tannin extraction

Tannin extraction methodpilot scale

The pilot-scale model was based on the PHWE process for the recovery of tannins from Norway spruce bark. The PHWE batch system used is similar to the system described by Plaza & Turner ([22]). The setup includes a pump, an extraction vessel, a heating oven and a collection vial. According to Plaza & Turner ([22]), the commercial PHWE system uses a multi-step process to extract chemicals from the same bark batch multiple times with fresh water. After each extraction, the extracts were collected in a vial to undergo evaporation and spray drying.

Tannin extraction experimentslaboratory scale

Laboratory-scale extraction from spruce bark was carried out to gather information about the extraction yields at different temperatures and process sequences. The experiments were done using bark removed from spruce logs of about 40 cm diameter at breast height, felled one week before the bark collection and then left exposed to natural weathering. The collected bark flakes, containing all layers of bark and trace amounts of woody tissue, were milled to a fine-powder (< 50 µm) with a vibrating disk mill (Herzog HSM 100H, Osnabruck, Germany). All ground bark samples were kept in the dark and in deep-freeze (-20 °C) until extraction.

The extractions were performed using an accelerated solvent extraction system (the ASE200 Dionex®, Sunnyvale CA, USA). Each extraction was then dried to a fine powder using a freeze dryer (Christ Alpha 1-4 LSC, Osterode, Germany). The dry extracts were analysed following the Folin-Ciocalteu method ([35]) to determine the total phenolic compounds content. The calibration was performed using highly purified quebracho tannins (FINTAN QP, Silvateam S.p.A., Italy). The phenolic concentration was then expressed as milligrams of purified quebracho tannin equivalents to milligrams of dry extracts. We assumed that the phenolic compound measured by the Folin-Ciocalteu method primarily corresponds to tannins, as reported by Bianchi et al. ([4]) and used the expression “tannin yield” for the total phenolic compounds later in the paper.

Two separate extraction sequences were conducted. Sequence 1 simulates the extraction process with only hot water. Approximately 2 g of milled bark powder was mixed with 1 g diatomaceous earth (diatomite) and loaded into a 22 ml ASE extraction cell. About 18 ml of tap water was added then heated to 90 °C within five minutes. After 20 minutes at constant temperature and pressure (10 MPa), the extract was flushed into the collection vessel. The process was repeated four times on the same bark sample, and extracts were collected in parallel vessels after each process. Sequence 2 was designed to study the extraction process with a preliminary step of cold-water extraction. The bark, prepared following the same procedure as Sequence 1, was initially extracted for 25 minutes with cold water (approximately 10 °C) and 10 MPa. The extraction then was continued using the same procedure as Sequence 1. Both Sequence 1 and Sequence 2 were repeated twice.

LCA methodology

Aim and scope definition

The aims of this assessment were: (1) to quantify the key environmental impact of pilot-scale dried tannin production to be used as raw material for environmentally friendly wood preserving agents; (2) to identify critical process stage(s) contributing to environmental load; and (3) to compare the impact of different extraction and post extraction process scenarios during the cradle-to-gate life cycle of bark extract ready to be applied as a preservative.

Standards, software and database

This LCA follows the guidance of ISO-14040 ([12]), ISO-14044 ([13]) and EN-15804 ([7]). LCA modelling, impact assessment and sensitivity tests were conducted with the SimaPro 8.0 software ([23]). If not otherwise specified, ecoinvent v3.0 ([39]) database was used for standard datasets.

Description of the system

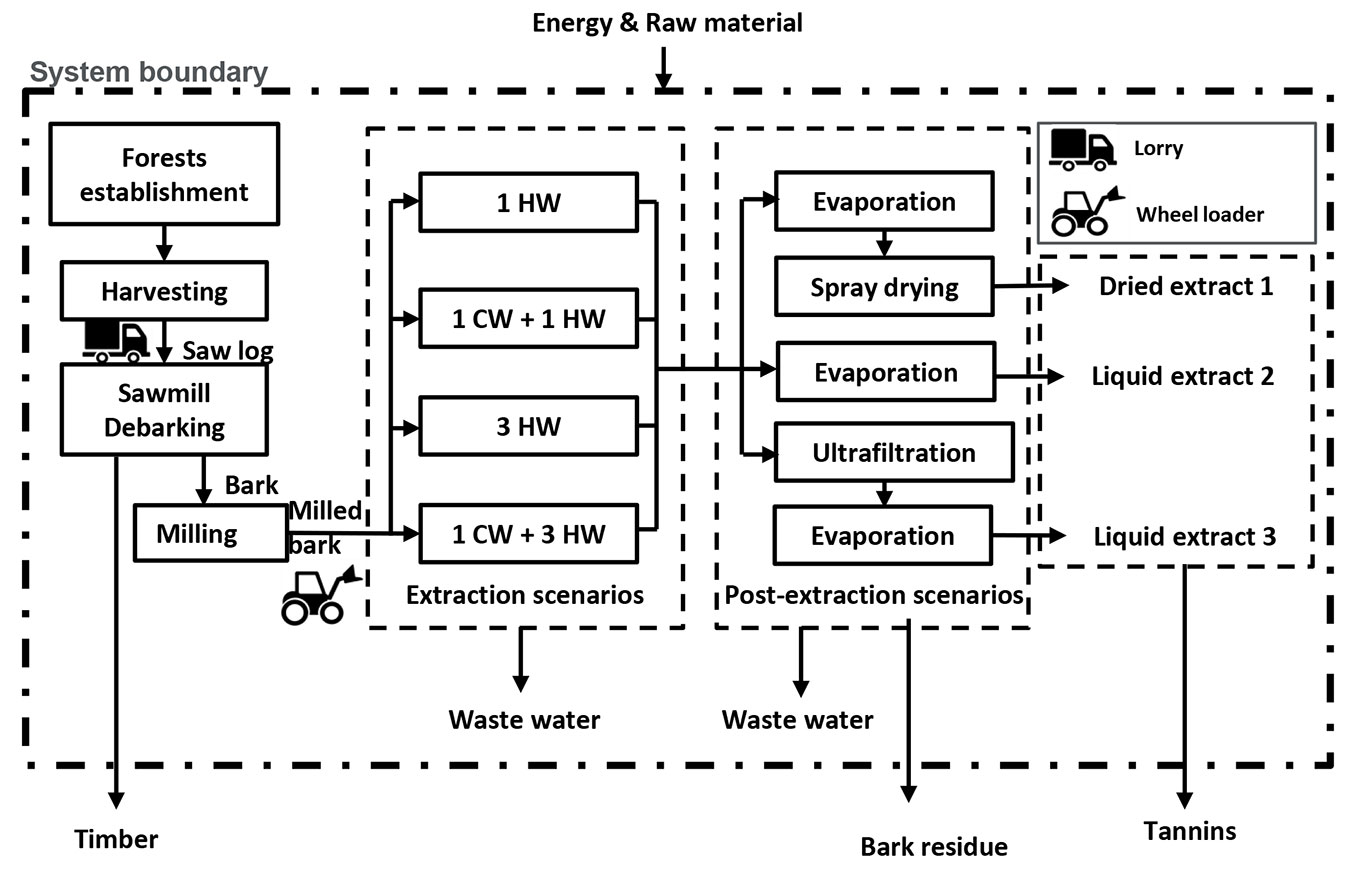

The system under study is described in Fig. 1. The following production stages were considered within the system boundaries: forest establishment and maintenance; spruce log harvesting and transportation to the saw mill; and debarking, bark milling, bark extraction and post extraction treatment. Harvested logs were transported by lorry (> 32 metric ton) from forest to sawmill. The bark extraction producer was assumed to be located next to a sawmill, and to use a wheel loader to carry out short internal transport of bark (5 minutes transportation time). The environmental impact of the bark and the bark residue after extraction are not within the system boundary.

Fig. 1 - System boundary for the tannin production. Detailed flow chart of the simulated tannin production unit operations from cradle to gate (CW: cold water extraction; HW: hot water extraction). The dash dot line describes the system boundary.

Allocation of environmental impact between by-products can be critical in LCA. The bark appears twice as a by-product in this system. The first allocation occurs after debarking at sawmill. Based on its economic allocation factor provided by Frühwald et al. ([9]), 1.2% of the environmental loads of the roundwood and debarking are attributed to bark chips. The second appearance occurs after the post extraction, when extracts have been produced and bark residue has left the system boundary as a by-product. The environmental impact between the bark residue and the extract flows were allocated according to the economic values of bark as an energy source and tannin as a product (see below).

Scenarios

The environmental impact of extract production was analysed based on combining one step of hot water extraction with evaporation and spray drying. To simulate possible industrial tannin productions, we have defined four extraction (E1, E2, E3, E4) and three post-extraction (P1, P2, P3) scenarios. Extraction scenarios refer to designed experiments, and the resulting solutions are treated after extraction, according to P1, P2 or P3 scenarios as listed in Tab. 1 and drawn in Fig. 1.

Tab. 1 - Tannin extraction (E) and post extraction (P) scenarios (30% is weight percentage (w/w) of all compound in extracts solution; 5% is weight percentage (w/w) of tannin in extracts solutions).

| Scenarios | Compound | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction | E1(1HW) | One step of hot-water extraction |

| E2 (1CW+1HW) | One step of cold-water extraction and one step of hot water extraction | |

| E3 (3HW) | Three steps of hot water extraction | |

| E4 (1CW+3HW) | One step of cold-water extraction and three steps of hot water extraction | |

| Post extraction | P1 | Extractives → evaporation to 30% → spray drying → dried extract1 |

| P2 | Extractives → evaporation to 5% → liquid extract 2 | |

| P3 | Extractives → ultrafiltration → evaporation to 5 % → liquid extract 3 |

P1 scenario

This scenario follows the method used in mimosa tannin production, a commercialized tannin production ([25]). The resulting liquid extracts after extraction are concentrated first by evaporator to 30% (w/w), and then by spray drying into the solid phase.

P2 scenario

This scenario is based on the idea that environmental and economic benefits might be obtained if the extract is concentrated just to the level that is assumed to be optimal in tannin content as a preservative. Thus, energy consumption, because of excess drying in P1, is avoided for preservative use since tannin needs to be mixed with water and other agents. Based on a previous study by Liibert et al. ([16]) and some unpublished results by other authors, we assume that a tannin concentration of 5% (w/w) is close to optimal.

P3 scenario

This scenario simulates the use of ultrafiltration equipment in industry to separate tannins from lower molecular weight compounds with lower energy requirements and greater efficiency ([18]). In the P3 scenario, the extract volume reduces during ultrafiltration by a factor of 1.76, as described by Pinto et al. ([20]), and the concentrate is further evaporated to the required tannin concentration level.

Functional Unit

The functional unit (FU) is 1 kg tannin yield after post extraction treatment. The equivalent masses of dried extracts used in P1 scenario were: 2.045 kg, 1.684 kg, 2.041 kg and 1.792 kg, corresponding to E1 to E4 scenarios. The equivalent mass of liquid extracts is 20 kg with the same tannin concentration (5%) for both P2 and P3, achieved by removing different amount of water in different E scenarios.

Inventory

Data source

Tannin yield through the PHWE process with different extraction method configurations were predicted using results from laboratory experiments. Ecoinvent v3.0 ([39]) was used as a main secondary data source, and other missing data were collected from literature and laboratory data (Tab. 2). The expected energetic value of bark residue and the market price of tannin were used for the allocations. Ecoinvent v3.0 suggests that 0.46 kg of bark is needed to produce 1 kWh of electricity, indicating an energy value of 2.17 kWh kg-1. As heat and electricity generation are frequently combined in Finland (i.e., CHP-technology), we use the energy price in heat production from forest chips in Finland 0.021 € kWh-1 ([28]) as a reference price, giving an estimated energy value of 0.046 € kg-1 for the bark residue. The market price of tannins is 1-2 € kg-1, according to the Technical Research Centre of Finland ([30]). Thus, 1.5 € kg-1 was considered to be a feasible value of the dried extract.

Tab. 2 - Collected data of energy consumption for each unit operation included to the model.

Data quality

To manage the ecoinvent’s global context and match the conditions of Finland geographically and temporally, all the electricity data were modified using the Finnish electricity grid mix according to the national statistics ([27]), in which the major contributors are nuclear energy (27.1%), net imports (21.5%), hydro power (15.9%) wood fuels (12.6%), hard coal (8.9%), natural gas (6.5%) and peat (3.8%).

Assumptions

The forest establishment and Norway spruce harvesting schemes are assumed to be like Sweden’s, since the forest management system and technology used in both countries are very similar ([3]). The average distance between forests and sawmills in Finland is 94 km, according to Karjalainen & Asikainen ([14]). In this study, it is assumed that extraction yield and extract composition on a pilot-scale matches the laboratory results under the same process conditions. To reduce the difference between ASE and PHWE, the amount of water used in ASE is adjusted to simulate PHWE extraction. ASE uses additional water to flush the bark after extraction. Thus, the actual water consumption in PHWE is less than in ASE extraction, which has been considered in the calculations. However, lack of a bark flushing might result in a lower recovery of extractives for PHWE than for ASE extraction. For the P3 scenario, the volume of the extract water solution after ultrafiltration is assumed to decrease by a factor of 1.76 ([20]). The efficiency of ultrafiltration process can vary, mainly depending on the membrane type and transmembrane pressure. According to Pinto et al. ([20]), as much as 93% of the extracted condensed tannins can be recovered. For simplicity, we assume that no tannins are lost after ultrafiltration, yielding a somewhat over-positive but recoverable estimate of the process performance. All equipment is calculated based on the assumption that it can produce 20.000 kg per year, throughout a 60-year service life. The equipment includes three boilers, two pumps, evaporators, spray dryers, an ultrafiltration facility, and storage tanks.

Impact categories

The impact assessment is based primarily on the CML-IA baseline method developed by the Center of Environmental Science of Leiden University ([6]). This method is widely used in Europe and covers all the indicators concerned in the EN-15804 ([7]), the European standard for Environmental Product Declarations for construction products. The seven impact categories are: Abiotic Depletion Potential Elements (ADPE); Abiotic Depletion Potential Fossil (ADPF); Global Warming Potential (GWP); Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP); Photochemical Ozone Creation Potential (POCP); Acidification Potential (AP); and Eutrophication (EP). In addition, the Cumulative Energy Demand (CED) is used to quantify all the used resources that have energy value (including fossil, nuclear, solar, geothermal, wind, hydropower and biomass) in tannin production.

Results

Tannin extraction experiments

The results of the laboratory-scale extractions are presented in Tab. 3 and Tab. 4. The figures are averages of the two independent experiments. The dried extract and tannin yields were measured for each step of the experiment. The cumulative dried extract yield and cumulative tannin yield were calculated by totaling the values of the previous steps. The cumulative tannin concentration of dried extracts was calculated by dividing the cumulative tannin yield by the cumulative dried extracts yield. The cold-water extraction step was not considered in the cumulative yields.

Tab. 3 - Dried extracts and tannin yield results from two laboratory extraction sequences; sequence 1 with four successive hot water extractions (steps 1-4) and sequence 2 with preliminary cold water extraction (step 0). The table presents the average results of two repetitions. (T): temperature; (d.b.): dry bark; (d.e.): dried extracts.

| Sequence | Step | T (°C) | d.e. yield in step (g kg-1 d.b.) |

Cumulative d.e. yield (g kg-1 d.b.) |

Tannin yield in step (g kg-1 d.b.) |

Cumulative tannin yield (g kg-1 d.b.) |

Cumulative tannin concentration (% d.e.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 90 | 78.5 | 78.5 | 38.4 | 38.4 | 48.9 |

| 2 | 90 | 18.7 | 97.2 | 9.5 | 47.9 | 49.3 | |

| 3 | 90 | 5.1 | 102.3 | 2.2 | 50.1 | 49.0 | |

| 4 | 90 | 4.1 | 106.4 | 1.5 | 51.6 | 48.5 | |

| 2 | 0 | 25 | 30.8 | - | 12.6 | - | - |

| 1 | 90 | 44.3 | 44.3 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 59.4 | |

| 2 | 90 | 14.5 | 58.8 | 7.5 | 33.8 | 57.8 | |

| 3 | 90 | 9.6 | 68.4 | 4.3 | 38.1 | 55.8 | |

| 4 | 90 | 7.5 | 75.9 | 3.1 | 41.2 | 54.3 |

Tab. 4 - Removed amount of water in different extraction (E1, E2, E3, E4) and post extraction (P1, P2, P3) scenarios.

| Post extraction scenario |

Extraction scenario |

Ultrafiltration (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | E1 | - |

| E2 | - | |

| E3 | - | |

| E4 | - | |

| P2 | E1 | - |

| E2 | - | |

| E3 | - | |

| E4 | - | |

| P3 | E1 | 68.52 |

| E2 | 103.79 | |

| E3 | 156.53 | |

| E4 | 210.56 |

Because the 4th step of extraction only produced 4.1 g extracts per kg of bark in Sequence 1 and 7.5 g per kg of bark in Sequence 2, only the first three steps were further considered. The results show the impact of adding one step of cold water extraction and of repeating the extractions on the obtained tannin concentration. Preliminary cold water extraction (E2 and E4) resulted in higher cumulative tannin concentration but lower yields (<34 g kg-1 dry bark) due to tannin loss in cold water. Repeated extractions (E3 and E4) resulted in higher cumulative dried extracts yields (≥24 g kg-1 dry bark) and higher cumulative tannin yields (≥12 g kg-1 dry bark) compared to single-step hot water extraction (E1 and E2). However, only minor variations in the tannin concentration were observed between one-step and three-step extractions (E2 and E4).

LCA inventory results of extraction and post-extraction

The amount of water to be removed after each post extraction scenario (Tab. 4) and the energy consumption for the FU were calculated based on the cumulative tannin concentration in dried extracts (Tab. 3) and on the defined scenarios (Tab. 1). Waste water does not include the water contained in bark residue. The inventories of extraction and post-extraction scenarios are presented in Tab. 5. Repeated extractions resulted in lower tannin concentrations, thus the energy consumption per FU was about 20 kWh higher after 3 hot water extractions. Because the total yield of tannin is lower after cold water extraction, more energy is consumed for the FU in E2 and E4 compared to E1 and E3.

Tab. 5 - Inventories for the FU (P1 P2 P3 scenarios). (*): Recovered energy is to present the possible benefit of burning bark residual in sawmill, as additional information, as it is not included in the system boundary. The values were calculated based on fresh bark heat capacity value.

| Kind | FU | Step | Unit | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Milled bark (dry) | kg | 26.1 | 38.0 | 19.9 | 26.2 | |

| Water | kg | 220.7 | 530.4 | 406.5 | 685.3 | ||

| Hot water extraction | kWh | 22.8 | 34.4 | 41.9 | 56.61 | ||

| P1 scenario | Evaporation | kWh | 211.1 | 326.3 | 494.4 | 669.5 | |

| Spray drying | kWh | 7.6 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 6.7 | ||

| P2 scenario | Evaporation | kWh | 192.8 | 306.3 | 476.1 | 650.0 | |

| P3 scenario | Ultrafiltration | kWh | 0.41 | 0.62 | 0.94 | 1.26 | |

| Evaporation | kWh | 97.5 | 162.0 | 258.5 | 357.3 | ||

| Output | Co-product (dry bark residue) | kg | 25.1 | 37.0 | 18.9 | 25.2 | |

| Tannin | FU | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Waste water (P1) | m3 | 0.16 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.62 | ||

| Waste water (P2) | m3 | 0.14 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.60 | ||

| Waste water (P3) | m3 | 0.14 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.60 | ||

| Recovered energy* | kWh | -43.0 | -63.6 | -30.4 | -42.3 | ||

Life cycle impact assessment

The environmental impacts and resource use to produce the FU are shown in Tab. 6. The reported impact categories are those required by EN-15804 ([7]). The non-renewable cumulative energy demand (CEDNR) is approximately double that of the renewable demand (CEDR). Also abiotic depletion potential of fossil energy (ADPF) is considerable lower than CEDNR. This is due to the Finnish electricity mix (see above), where the main electricity source is nuclear power and only 28.5% of the electricity comes from renewable sources. ADPF impact assigns mostly to coal (45.5%) and natural gas (37.9%) having a low share in the electricity mix. GWP consist almost solely on carbon dioxide emissions (90%). Emissions to ground (63.4% of AP is sulfur oxide) and water (73.5% of EP is phosphate) are related to the energy use for evaporation.

Tab. 6 - Life cycle impact assessment results of the FU, P1, E1 scenario.

| Kind | Impact category | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impact | Abiotic Depletion Potential Elements (ADPE) | kg Sbeq | 1.27E-05 |

| Abiotic Depletion Potential Fossil (ADPF) | MJeq | 4.55E+02 | |

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | kg CO2eq | 4.11E+01 | |

| Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP) | kg CFC-11eq | 4.22E-06 | |

| Photochemical Ozone Creation Potential (POCP) | kg C2H4 eq | 6.89E-03 | |

| Acidification Potential (AP) | kg SO2 eq | 1.20E-01 | |

| Eutrophication (EP) | kg PO4-3eq | 5.22E-02 | |

| Resource use | Cumulative Energy Demand, Non-renewable (CEDNR) | MJeq | 1.29E+03 |

| Cumulative Energy Demand , Renewable (CEDR) | MJeq | 6.81E+02 |

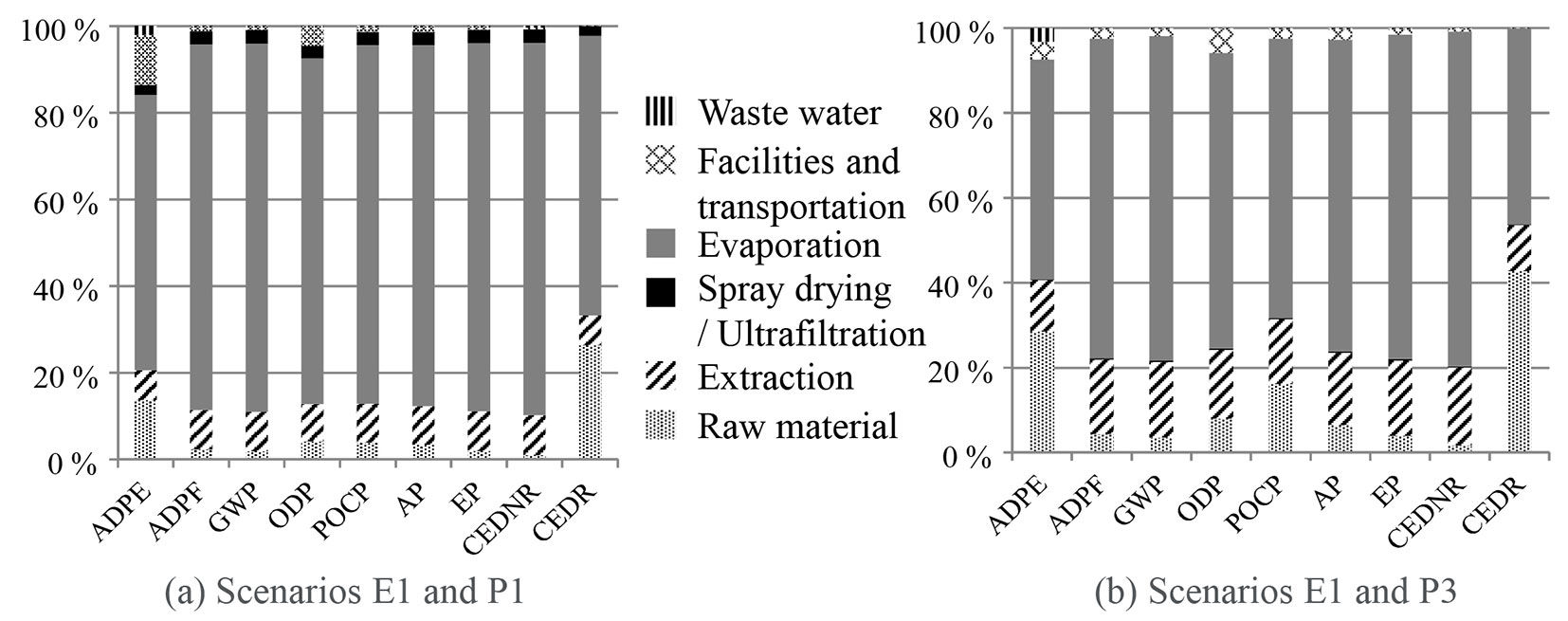

High energy intensity of evaporation and extraction is indicated as their relative high contributions in each impact category (Fig. 2). Raw material extraction (bark and water) contributes to the renewable energy demand due to the gross calorific value of sawed logs with bark based on solar energy (8772 MJ m-3, ecoinvent v3.0 database). Its possible use as a system process energy is not discussed here due to the multiple alternative uses of this process residue.

Fig. 2 - Contribution of process stages on impact and resource categories. Figure 2a scenario P1 and E1, Figure 2b scenarios E1 and P3. Abbreviations: (ADPE): Abiotic Depletion Potential Elements (kg Sb eq); (ADPF): Abiotic Depletion Potential Fossil (MJ); (GWP): Global Warming Potential (kg CO2 eq); (ODP): Ozone Depletion Potential (kg CFC-11 eq); (POCP): Photochemical Ozone Creation Potential (kg C2H4 eq); (AP): Acidification Potential (kg SO2 eq); (EP): Eutrophication (kg PO4-3 eq) ); (CEDNR): Cumulative Energy Demand (MJeq), Non-renewable; (CEDR): Cumulative Energy Demand Renewable (MJeq). Raw material includes bark extraction and water; Facilities includes PWHE, evaporator and spray dryer).

Scenario comparisons

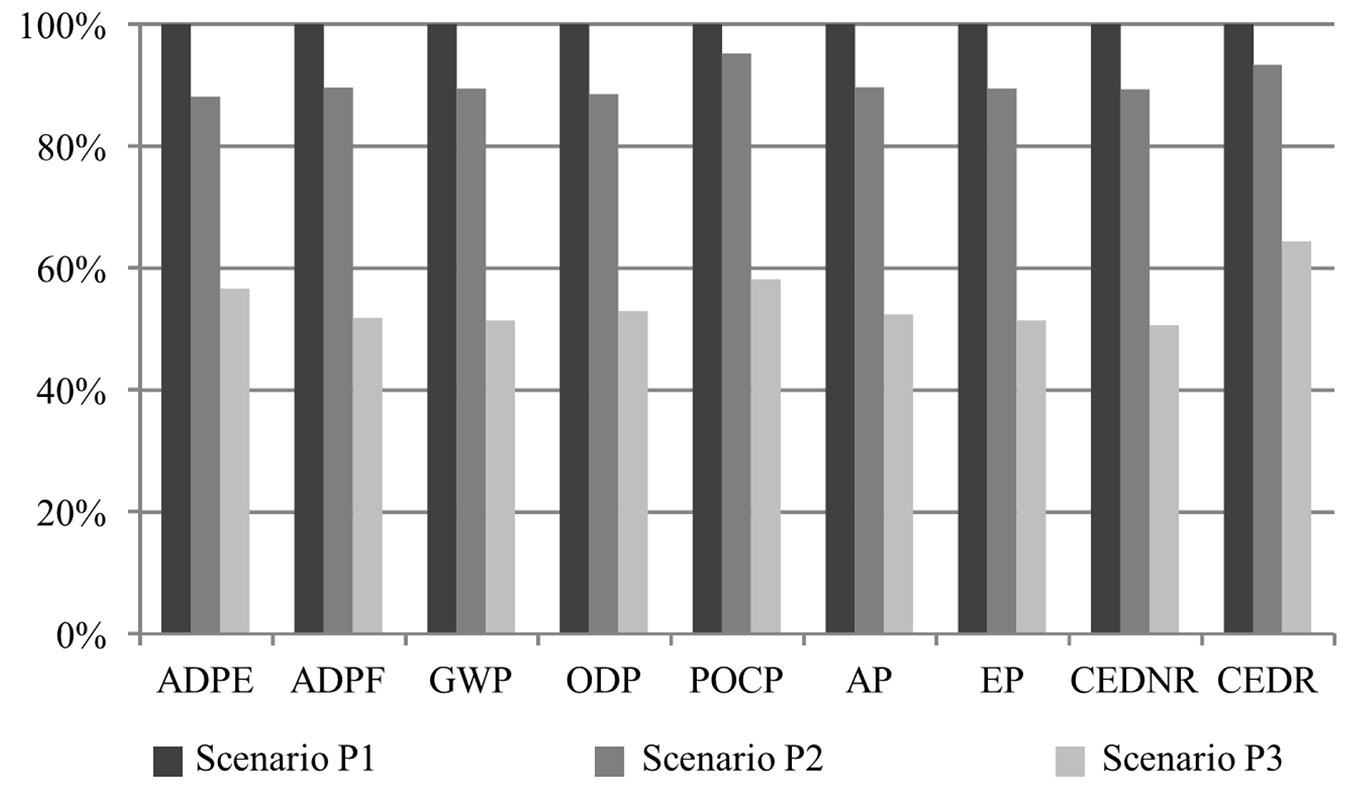

The environmental impact of the proposed extract post-treatments (P scenarios) was compared first. While evaporation made the largest contribution to the impact in P1, Fig. 3 provides quantified support for an optimization of the process. The results indicate that both alternative scenarios (P2 and P3) perform better in all impact categories. The P2 scenario has slightly less impact compared to P1 because most of the water contained in the extracts should still be evaporated, keeping the energy intensity high. If the tannin-containing extracts can replace water in the preservative solution, the environmental gains are moderate. In real-life cases, the difference might be even smaller as one should also account for a lower environmental burden from transportation of the dried extracts (P1) relative to liquid extracts (P2).

Fig. 3 - Environmental impacts for the production of one functional unit. Comparison of post extraction scenarios P1, P2 and P3 after hot water extraction (E1). (ADPE): Abiotic Depletion Potential Elements (kg Sb eq); (ADPF): Abiotic Depletion Potential Fossil (MJ); (GWP): Global Warming Potential (kg CO2 eq); (ODP): Ozone Depletion Potential (kg CFC-11 eq); (POCP): Photochemical Ozone Creation Potential (kg C2H4 eq); (AP): Acidification Potential (kg SO2 eq); (EP): Eutrophication (kg PO4-3 eq); (CEDNR): Cumulative Energy Demand (MJeq), non-renewable; (CEDR): Cumulative Energy Demand Renewable (MJeq).

The P3 scenario has roughly half of the impact of P1. The extract volume reduces remarkably, and the energy needed for ultrafiltration is low ([2]). In addition, analysis of the relative contribution of the environmental stages (Fig. 2, right panel) indicates that the percentage of evaporation decreases compared to the P1 scenario, e.g., the relative contribution of GWP is reduced from 86% to 77%. In addition, ultrafiltration can promote the enrichment of tannins in products, according to Pinto et al. ([20]), which might increase the effectiveness of the extract as an antifungal agent. However, there might be some tannin loss after ultrafiltration, which would lead to a yields reduction. According to the Fig. 3, P3 scenario might loss its environmental advantage if more than half of tannin is lost after the ultrafiltration process.

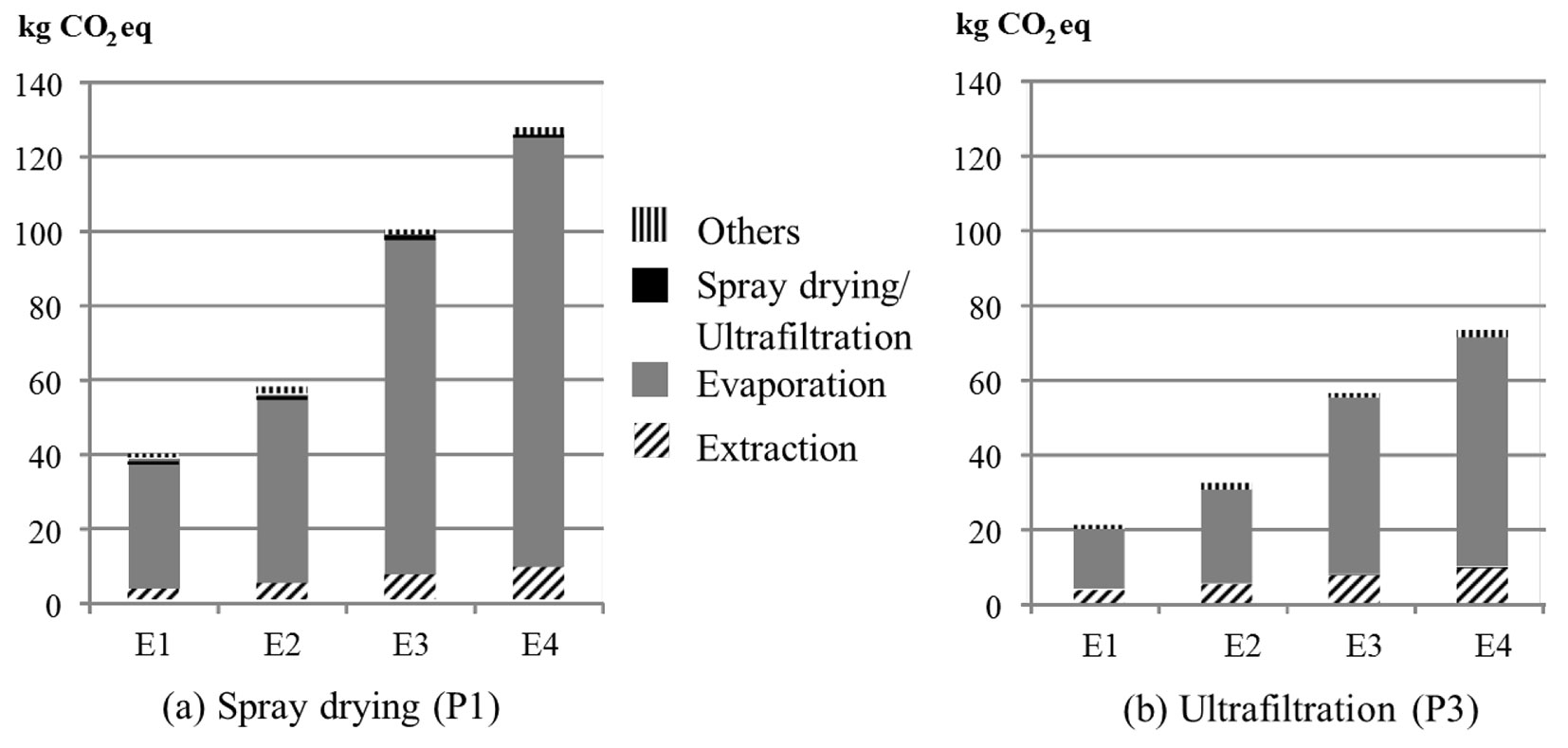

The GWP of dried extracts production through the four proposed extraction scenarios are compared in Fig. 4. The E1 scenario has the lowest impact, followed by scenarios E2, E3 and E4. The post extraction scenarios (P1, left panel and P3, right panel) do not change the order of extraction scenarios, but has a considerable impact on the total GWP of the FU. Both repeated extractions and preliminary cold water extractions cannot improve the environmental performance of the production of the FU. Even if a higher tannin concentration in dried extracts (P1), achieved by preliminary cold water extraction, means that less bark is needed for the FU, the total tannin loss still causes higher environmental burdens. Repeating the extractions requires continuously adding fresh water, which means that a greater amount of water and a higher amount of energy will be consumed.

Fig. 4 - Comparison of (a) spray drying (P1) and (b) ultrafiltration (P3). Global warming potential of producing 1 FU. Other stages represent the aggregated stages of raw material, facilities, transportation and waste water treatment.

Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity test was carried out by examining the results if a change of 10% input was simulated. The results are sensitive to the electricity mix (7.3% to 9.8% in all categories for a 10% input change) because electricity will influence the stages of evaporation, hot water extraction, spray drying and ultrafiltration. The evaporation stage is the largest contributor to the environmental profile in the production of the FU. The results are not sensitive (less than 1% for a 10% input change) to the other upstream processes, including bark chips preparation, internal transportation and facilities preparation, as well as downstream processes (including waste water treatment). The evaporation stage has clearly the most influence on the modelled profile. And a 10% of increase would lead to a 6.4% to 8.5% increase in the results. Therefore, more accurate results can be attained if more practical data can be acquired from industry.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the environmental impact of hot water extraction of tannins from spruce bark and to illustrate how the LCA tool can be used to support this kind of process under development. The extraction experiments and the literature based inventories should both be considered preliminary, since scaling up the processes has not been thoroughly assessed. The main limitation of this study is that tannin yields at a pilot-scale plant might be different from the laboratory experiment (e.g., different temperatures, bark and storage times). Therefore, more data from extraction plants should be collected in the future.

However, the evidence found on the critical importance of evaporation as a post-extraction treatment and the resulting low environmental performance of multi-extraction processes is rather evident in the batch extraction case. The key to improve environmental performance appears to be a lower amount of water use for the extraction process. Stather ([26]) described another tannin extraction method using a group of flow-through tanks, which is the most common process in current industrial practice. This method might be more efficient since, instead of using fresh water to extract from the same batch of bark, the system allows extract solutions to continuously flow through other tanks to perform the extraction. It would be worthwhile to study the environmental performance of flow-through methods.

Ultrafiltration also appeared to be a promising post-extraction technology from an environmental point of view. It not only reduces the extract volume but also filters away some of the undesired, smaller-sized molecules like monosaccharides and other monomers, thus improving the quality of the extract for use as a preservative. It should be also noticed that tannin retention after ultrafiltration process contributes significantly to the result. Therefore, it is crucial to select the proper membrane type and the processing conditions. Because the related literature on ultrafiltration is more focused on the phenolic compound concentration than on sugars, further studies on compounds (molar mass and their chemical characterization) in permeate and rejected fractions is needed.

High energy intensity of evaporation rests partly on the selected system boundary. In this study, we assumed that the bark is taken from the sawmill and returned after extraction to its original use as energy for kiln drying. Alternatively, we could have assumed that the bark residue is used as an energy source for the extraction. If the bark residue is incinerated and the generated energy is used within the system, the global warming potential would be approximately 65% of the one found here. However, if no excess bark is available at the mill, fossil fuels are likely used, at least partly cancelling the gain in extraction. Even if this might be more realistic, the selected system boundaries serve the process development better.

Conclusions

This study establishes a cradle-to-gate environmental analysis of a tannins pilot-scale extraction from Norway spruce bark through PHWE. The focus is to compare different extractions and post-extraction scenarios. The evaporation process is the largest contributor to all environmental impacts and resource use categories. The use of ultrafiltration can halve the environmental burdens if all tannins are recovered. Although tannin yields are higher, preliminary cold water extraction and multiple extractions have a higher environmental impact for 1 kg of tannin than a single hot water extraction. Preliminary cold water extraction and ultrafiltration might be beneficial processes in terms of obtaining less non-tannin compounds, including sugars, which might be used in metabolizing the fungi in dried extracts.

The utilization of spruce bark tannins as an antifungal agent is still in development. Some other issues than tannin purity are also arising, e.g., the solubility of tannin in water which makes it hard to bind it to wood tissues. It is also disputable to what extent tannin-based preservatives can increase the service life of wood products. However, this paper offers a novel platform for future studies on tannin extraction methodologies and applications for wood impregnation so that if more data become available, more solid LCA results can be provided. This would allow an accurate study of the entire value-chain of tannin-impregnated wood.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge COST Action FP1407 and STSM- 33649 for support.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Petri Kilpeläinen

Tarmo Räty

Natural Resources Institute Finland - Luke, Helsinki (Finland)

Christelle Ganne-Chédeville

Bern University of Applied Sciences, Institute for Materials and Wood Technology, Biel (Switzerland)

Antti Haapala

University of Eastern Finland, School of Forestry, PO Box 111, 80101 Joensuu (Finland)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Ding T, Bianchi S, Ganne-Chédeville C, Kilpeläinen P, Haapala A, Räty T (2017). Life cycle assessment of tannin extraction from spruce bark. iForest 10: 807-814. - doi: 10.3832/ifor2342-010

Academic Editor

Giacomo Goli

Paper history

Received: Jan 02, 2017

Accepted: Jun 13, 2017

First online: Sep 25, 2017

Publication Date: Oct 31, 2017

Publication Time: 3.47 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2017

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 56490

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 43583

Abstract Page Views: 5522

PDF Downloads: 6099

Citation/Reference Downloads: 37

XML Downloads: 1249

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 3059

Overall contacts: 56490

Avg. contacts per week: 129.27

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2017): 31

Average cites per year: 3.44

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Hygroscopicity of the bark of selected forest tree species

vol. 10, pp. 220-226 (online: 06 November 2016)

Research Articles

Comparison of extractive chemical signatures among branch, knot and bark wood fractions from forestry and agroforestry walnut trees (Juglans regia × J. nigra) by NIR spectroscopy and LC-MS analyses

vol. 15, pp. 56-62 (online: 08 February 2022)

Research Articles

Tree growth, wood and bark water content of 28 Amazonian tree species in response to variations in rainfall and wood density

vol. 9, pp. 445-451 (online: 16 January 2016)

Research Articles

Pilot-scale drying of southern pine (Pinus spp.) lumber in a heated tube dryer

vol. 18, pp. 10-15 (online: 02 February 2025)

Research Articles

Assessment of timber extraction distance and skid road network in steep karst terrain

vol. 10, pp. 886-894 (online: 06 November 2017)

Research Articles

Effect of stand density on longitudinal variation of wood and bark growth in fast-growing Eucalyptus plantations

vol. 12, pp. 527-532 (online: 12 December 2019)

Research Articles

Compositions of compounds extracted from thermo-treated wood using solvents of different polarities

vol. 10, pp. 824-828 (online: 25 September 2017)

Research Articles

Modifying harvesting time as a tool to reduce nutrient export by timber extraction: a case study in planted teak (Tectona grandis L.f.) forests in Costa Rica

vol. 9, pp. 729-735 (online: 03 June 2016)

Research Articles

Deploying an early-stage Cyber-Physical System for the implementation of Forestry 4.0 in a New Zealand timber harvesting context

vol. 17, pp. 353-359 (online: 13 November 2024)

Research Articles

Fuel consumption comparison of two forwarders in lowland forests of pedunculate oak

vol. 12, pp. 125-131 (online: 11 February 2019)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword