Assessment of age bias in site index equations

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 9, Issue 3, Pages 402-408 (2016)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1548-008

Published: Jan 11, 2016 - Copyright © 2016 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

The most widely accepted method of evaluating site productivity is site index. In spite of some important restrictions it is still a useful concept in both forest research and management. One of the most important challenges when using site index is an age trend manifested by a negative correlation between site index and stand age. Age trend may result from the inappropriateness of site index models. In this paper we develop a new approach for assessing age bias in site index models. Field data collected from 311 sample plots established in Norway spruce stands in the Polish region of the Carpathians formed the basis of this study. In the proposed approach the appropriateness of site index models is assessed by analyzing the existence of age trends in residuals of geocentric site index prediction models. Using the developed approach we demonstrated that when significant correlations exist between residuals of site index prediction models and stand age, it likely indicates the existence of an age trend and thus the inappropriateness of site index model. To remedy this situation, we demonstrated that the observed age trend can be quantified and utilized in new, non-biased, site index models.

Keywords

Site Productivity, Age Trend, Climate Change, Height Growth, Site Index Model

Introduction

Site productivity is a quantitative estimate of the potential of a site to produce plant biomass ([38]). Forest site productivity remains a fundamental variable in forestry ([6]). Reliable estimates of potential site productivity are essential for sustainable forest management, as it is often a key criteria when considering site- and species-specific decisions concerning species composition, silvicultural treatments, determining allowable cut, rotation period and forecast of timber yield ([45], [33]). To be most useful for modeling and prediction, a measure of site quality must be quantitative, that is expressed by a number ([12]).

The most commonly used and widely accepted method of evaluating site productivity is site index ([38], [37]). In spite of the fact that in many cases site index is not always sufficient to characterize site productivity ([6]), it is still one of the most widely used indicators of wood production and is useful in both forest research and management ([39]). Therefore, the construction of site index models remains a fundamental task for site productivity differentiation ([38], [39], [37]).

One of the most important challenges in the site index concept is an age trend manifested by a negative correlation between site index and stand age, which has been frequently reported ([18], [40], [3], [30], [36], [49]). In most studies problems associated with age trend in site index resulted from changes in site conditions caused by non-static factors: nitrogen deposition, increasing CO2 concentration and climate change ([18], [21], [34], [19], [43], [30], [36], [6], [49]). Highly productive forests are usually managed under short rotation, and consequently older stands may be over-represented on infertile sites, since they require a longer time to reach a certain goal of wood production which also can cause an age trend in site index estimates ([47], [30], [49]).

In a study conducted in Sweden, Johansson ([23]) found significant variation in site index curves of forest stands due to mineral soil type and geographical location. Effect of genetic variability on the height development of trees and resulting age trends were also reported by Adams et al. ([1]). Genetic variability has been identified as the factor modifying the trajectory of site index curves by Buford & Burkhart ([11]), who found that the site index curves developed for different provenances differed in their parameters describing the asymptote for height growth. Climate, soil and genotype-by-environmental interactions can favor the adaptation of species to local ecological conditions, causing variable height patterns for the same species among ecoregions ([28], [4]). Significant differences in the pattern of tree heights can also occur for the same species, even within a given site index class ([27]). García ([20]) reported that three sources of height growth development variability can be identified: (a) between sites, (b) within sites, and (c) observation error. The differences between site index model trajectories with age may also result both from the method and data used in deriving site equations ([14], [15]).

In order to avoid age bias in site index prediction, Sharma et al. ([36]) included age as one of the predictor variables in site index prediction models for Norway spruce in Norway and obtained an increase in the proportion of explained variance. Including age as one of the variables reduces bias of site index prediction model; however, in such cases the problem with age trend in the site index model still remains unsolved. A different approach was used by Bøhler & Bernt-Håvar ([5]), which proposed a linear correction of site index models in order to take into account the inappropriacy of site index model for Norway spruce resulting from age trend in high altitude semi-natural old stands in Norway.

In summary, an accurate site index model should take into consideration age trends irrespectively of its source, and ignoring these potential biases will cause erroneous assessment of site productivity. Therefore, there is a need to have a practical procedure which allows managers to assess if particular site index models are sufficiently reliable for describing the site productivity of given tree species in areas of interest. In the case of a lack of adequate models, it follows there is a further need to develop more appropriate models by fitting base-age invariant dominant height equation. The decision as to whether existing site index models are sufficiently accurate or whether new site-specific site index models are required for local site conditions should be based on consistent and well developed criteria. However, in the forestry literature the aspect of adequacy of site index models which is very important both from the practical and scientific view point has rarely been analysed. In most cases authors suggested inappropriateness of site index models based on simple comparisons of site index curves obtained from stem analysis or permanent sample plots with site index models or tables. These comparisons assume that the collected tree or plot observations data effectively describes changes in stand height with age. However, the appropriateness of such assumptions is not valid in many cases and just because the measured and modeled height does not match, it does not mean the site index equation is bad.

In this paper we develop a new approach for the assessment of site index models. In the proposed approach the appropriateness of site index models is assessed by analyzing the existence of age trends in residuals developed using forest inventory data and environmental characteristics. According to the developed procedure, a significant correlation between residuals of site index prediction models and stand age indicates the existence of a bias resulting from an age trend and thus the inappropriateness of site index model. We used residual values of site index prediction models instead of a direct correlation of site index models with age in order to remove frequently observed effects of over-representation of older stands on infertile sites or other types of unequal distribution of sample plots in given ages on different environmental gradients. In cases where site index models have a demonstrated age trend we proposed a correction procedure which takes into consideration the age trend found during the validation process by incorporating it into the new site index model.

Material and methods

A case study area and sample design

Norway spruce stands in the Polish part of Western Carpathians (18o 48′ 50″ E and 19o 58′ 58″ E longitude, 49o 23′ 52″ N and 49o 41′ 3″ N latitude) formed the basis of this study. Field data were collected from 311 sample plots located in even-aged spruce stands aged 40-157 years. The stands were located between 540-1360 m a.s.l. Sample plots were located in a regular (1250×1250 m) grid and were circular ranging in size from 0.02-0.10 ha. The lowest number of trees per plot was 8 and the maximum 62, with an average of 27. Tree height and diameter at breast height were measured for all trees in the sample plots.

Top height of individual plots was calculated from the mean height of the 100 largest trees per hectare. The age of each plot was determined from at least six dominant trees by counting the number of rings on increment cores extracted using an increment borer at a height of between 20-30 cm above the ground surface, adding 3 years to reach the point of extraction. In general, the difference in age among individual trees in the sample plots was less than 3-5 years.

At each plot the characteristics of topography and the geological substratum were also assessed. Topography was described by the elevation above the sea level (E) measured with the use of an altimeter, the aspect (A) measured in degrees with a compass, the slope (S) and the landform category (Lc). Landform category was derived from a 10×10 m digital terrain model using a combination of topographic position indexes for the scale of 300 and 2000 meters. Geological substratum (Gs) was estimated for individual plots using the geological map in the scale of 1:50 000. For the modeling purpose, the aspect values were transformed as follows (eqn. 1):

where KB is the transformed value of aspect, varying from 0 to 2, A is the aspect expressed by azimuth (degrees), Amax is the assigned direction (azimuth) of maximum importance, the value Amax = 45° was assumed.

In the analysis the relationships between the site index and predictor variables were investigated using generalized additive models (GAM, [22] - eqn. 2).

where Y is the dependent variable, Xi are the predictor variables, G is the link function, f1, f2, …, fn are smoothing spline functions estimated from the data, β is a free term, and the errors ε are assumed to have constant variance and mean of 0.

GAM’s were selected as the tool for analysis because they are ranked as one of the most sufficient modeling techniques for the development of site index prediction models ([2]). The relationship between residuals of GAM models and age of the stands was analyzed using standard linear models.

The procedure of validation of site index models

The proposed method of validation and correction of site index models was applied to three site index models used in practice for Norway spruce in Poland.

(1) An anamorphic site index model for Norway spruce in Poland (SIB) developed by Bruchwald et al. ([9]) using the stem analysis data collected from 548 Norway spruce stands located at the lowland area of North-eastern and mountain area of southern Poland (eqn. 3):

where SIB denotes the site index with a base age of 100 years, H is the top height of the stand, and AT is an age-dependent function defined as (eqn. 4):

where T denotes the age of the stand in years.

(2) The site index model describing Lorey mean height growth trajectories from Schwappach ([35]) yield tables (SIS) developed with the use of base age specified method (eqn. 5):

where HL is the Lorey mean height at the age T.

(3) The site index model for Norway spruce in Polish Mountains (SIM) developed using the GADA method based on height growth trajectories obtained from stem analysis of 162 individual trees measured from 53 sample plots located in the Polish Carpathians ([41] - eqn. 6):

where H is the top height at the age T and R is defined as (eqn. 7):

The proposed validation procedure of the site index models described above is outlined as follows. Initially, each site index model was used for the calculation of site index values for all of the sample plots. Two approaches were then developed to assess the adequacy and validity of these site index estimates.

First, the relationship between the site index calculated on the basis of eqn. 3, eqn. 5 or eqn. 6 and the available environmental variables is modeled using the developed GAM. The result of this analysis is a site index prediction model describing the site index as a function of a number n of site characteristics Xn (eqn. 2). The adequacy of site index models to the local conditions is validated based on the relationship between the residuals from the model fitted in step 2, and stand age. The existence of a significant correlation between the residuals from the site index prediction model and stand age implies that there are systematic errors in the site index determination.

Secondly, we demonstrated an alternative approach using the age of the stands as one of the independent variables in the site index prediction model (SIPM). In this case the significance of “age” as an independent variable in SIPM demonstrates the inadequacy of site index model. As a result, the height of stands in base ages will be under- or overestimated. The “+” sign of the parameter connected with the variable “age” in SIPM model indicates that site index for young stands is underestimated and overestimated for older stands. In the opposite case a “-” implies overestimation of site index for young and overestimation for old stands.

Procedure of temporary adjusting of site index model to local site conditions by incorporating age trend

Assuming that a site index model is proven invalid, we proposed a simple procedure to adjust the model to the local growth conditions. Using the regression model describing the relationship between residuals of the site index prediction model and the stand age, it is possible to determine the error in the predicted site index as a function of stand age. The relationship between the residuals of the site index prediction model and the stand age can be described both using a simple linear regression model (eqn. 8):

where δSIPM is the error of site index prediction model, β0 is the model parameter, T denotes the stand age and ε the random residual error of the equation.

The site index of the stand at a given age is then corrected by subtracting the correction factor calculated as the difference between the calculated SI and the error described by eqn. 9, which subsequently removes the age trend from site index model (eqn. 9):

where SIcor denotes the corrected value of site index, SI denotes the value of the site index calculated on the basis of the validated model, and δSIPM denotes the error of the site index prediction model calculated from eqn. 8.

The above procedure allows systematic errors from inadequate models due to age trend to be minimized. It should be noted, however, that the eliminated systematic errors are also free from the influence of unbalanced distribution of sample plots across different site conditions. Using the proposed approach, it is also possible to adjust invalid site index models using a correction factor Icor, defined as (eqn. 10):

where SIE denotes the observed (existing) value of site index, and (eqn. 11):

where HT is the height of the stand at specified age T, and HBA is the height of the stand in a base age.

Corrected value of the stand height trajectory (Hcor) in a certain age is calculated by its multiplication by the correction factor (Icor) according to the following equation (eqn. 12):

Results

Validation of Bruchwald’s site index model (SIB)

Tab. 1 - Site index prediction models describing the relationship between site indexes calculated using the assessed site index models used for Norway spruce in Poland (SIB, SIS and SIM) and selected predictor variables developed using generalized additive models techniques.

| Dependent variable - site index model (model source) |

Predictor variables |

Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|

| SIB ([9]) | elevation above sea level (E), product of slope and aspect (S×KB), landform category (Lc), geological substratum (Gs) |

71.8 |

| SIB ([9]) | elevation above sea level (E), product of slope and aspect (S×KB), landform category (Lc), geological substratum (Gs), stand age (T) |

81.6 |

| SIS ([35]) | elevation above sea level (E), product of slope and aspect (S×KB), landform category (Lc), geological substratum (Gs) |

80.4 |

| SIS ([35]) | elevation above sea level (E), product of slope and aspect (S×KB), landform category (Lc), geological substratum (Gs), stand age (T) |

81.6 |

| SIM ([41]) | elevation above sea level (E), product of slope and aspect (S×KB), landform category (Lc), geological substratum (Gs) |

81.2 |

| SIM ([41]) | elevation above sea level (E), product of slope and aspect (S×KB), landform category (Lc), geological substratum (Gs), stand age (T) |

81.5 |

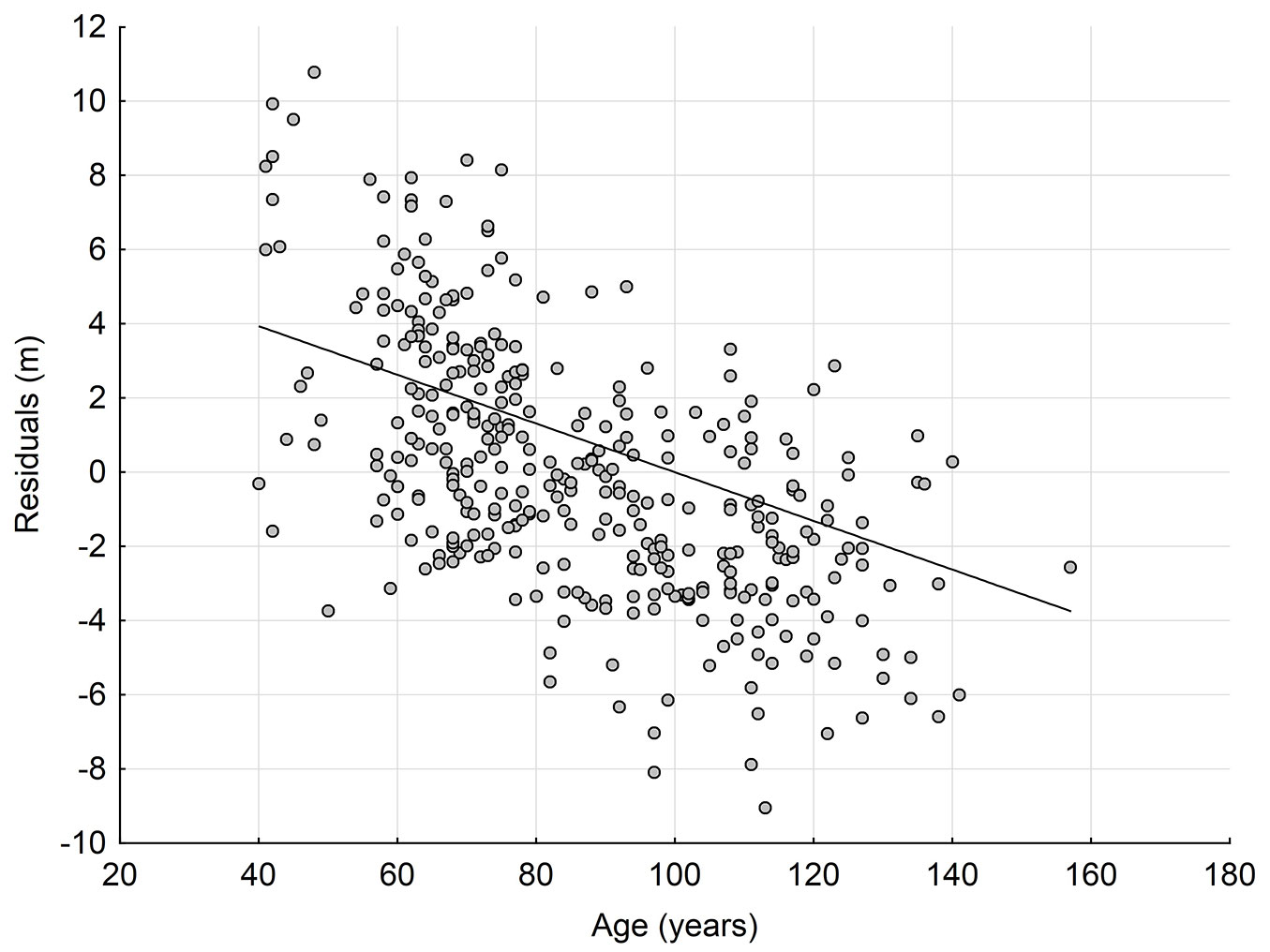

Fig. 1 - Relationship between residual values (obs-pred) of the site index prediction model based on validated site index model SIB ([9]) and the age of stands.

Tab. 2 - Characteristics of the models describing the relationship between residuals of site index prediction models and the age of stands (eqn. 7).

| Site index model |

Value of parameter |

R 2 | p-level |

|---|---|---|---|

| SI B | -0.06551 | 0.34 | <0.00001 |

| SI S | -0.01116 | 0.17 | 0.00029 |

| SI M | 0.00212 | 0.01 | 0.89331 |

First, a local site index GAM model describing SIB as a function of site characteristics was developed. It was found that the site index calculated using the Bruchwald et al. ([9]) model was significantly correlated with site characteristics including altitude, product of slope and elevation (S × KB), geological layer and landform category (Tab. 1), and explains 71.8% of the variability of site index (SIB). Residuals from this site index prediction model were significantly correlated with the stand age (T), which explain over 34% of the variability (Fig. 1, Tab. 2). This relationship was described by linear regression model (eqn. 13):

where δSIB denotes the error of site index estimation using the site index prediction model, and T the age of the stand.

Using the second approach that included “age” into site index prediction model, the proportion of explained variance significantly increased to 81.6% (Tab. 2).

Applying our approach, the observed significant correlation between residuals of the site index prediction model and the stand age, as well as the significance of the age variable in the SIPM age trend, implied an age trend bias and indicated the inadequacy of the SIB model under local site conditions. This inadequacy results in systematic errors in site index estimation.

Validation of site index model by Schwappach (SIS)

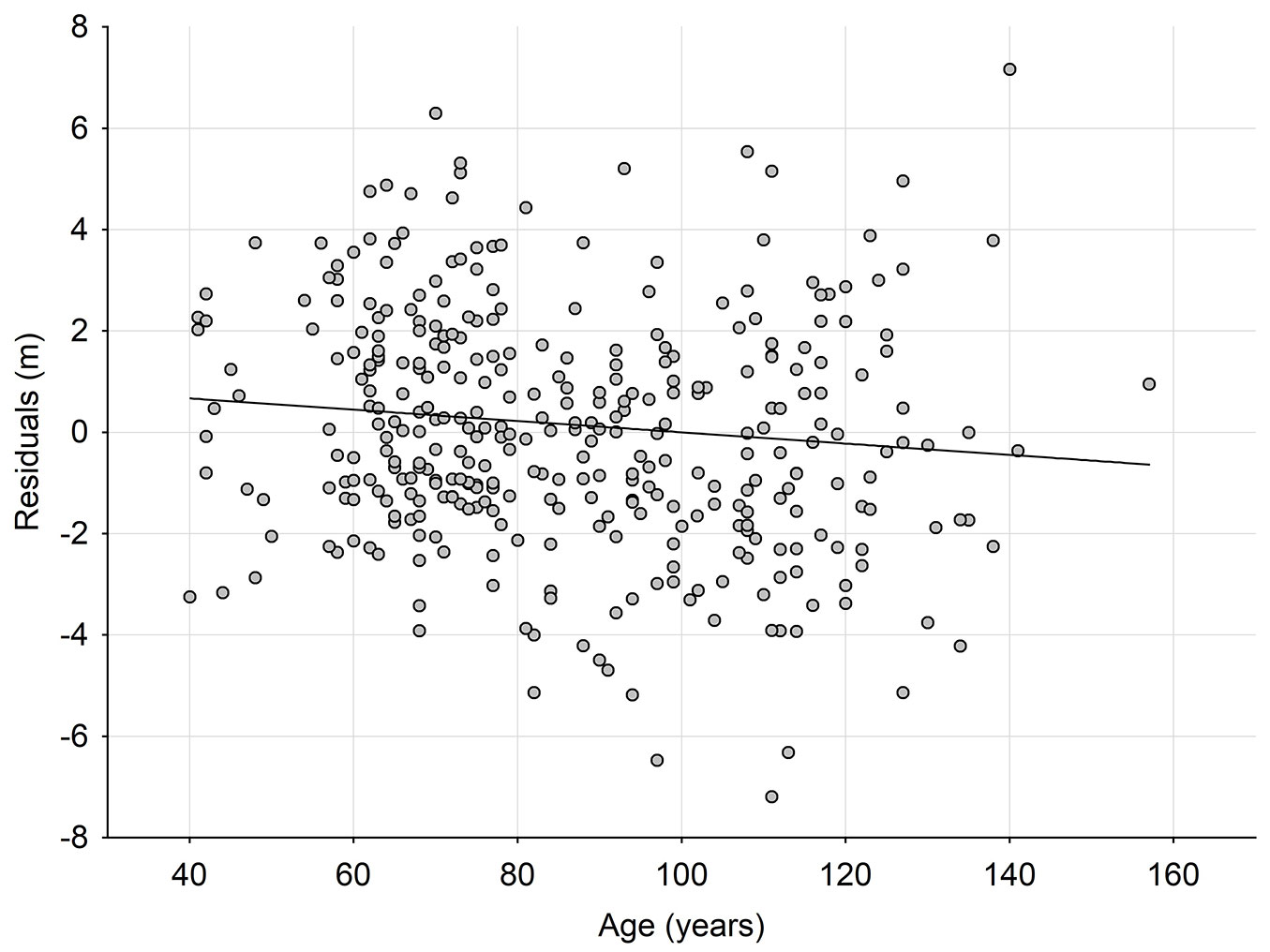

Site indexes SIS were calculated using the site index model by Schwappach ([35]) and used as dependent variables in a GAM site index prediction model. In this case, the variance explained by the model (80.4% - Tab. 1) is substantially higher than the variance of the site index prediction model developed using SIB as the dependent variable. By including the variable “age” in this site index prediction model, the variance only slightly increases to 81.6%. Also, stand age was a significant variable when added to the SIMP equation. However, residuals of the site index prediction model are weakly correlated with the stand age (T) explaining only about 17% the total variation (Fig. 2, Tab. 2).

Fig. 2 - Relationship between residual values (obs-pred) of site index prediction model developed for site indexes calculated on the basis of Schwappach ([35]) site index model SIS and age of the stands.

Validation of the site index model for Norway spruce Polish ountains (SIM)

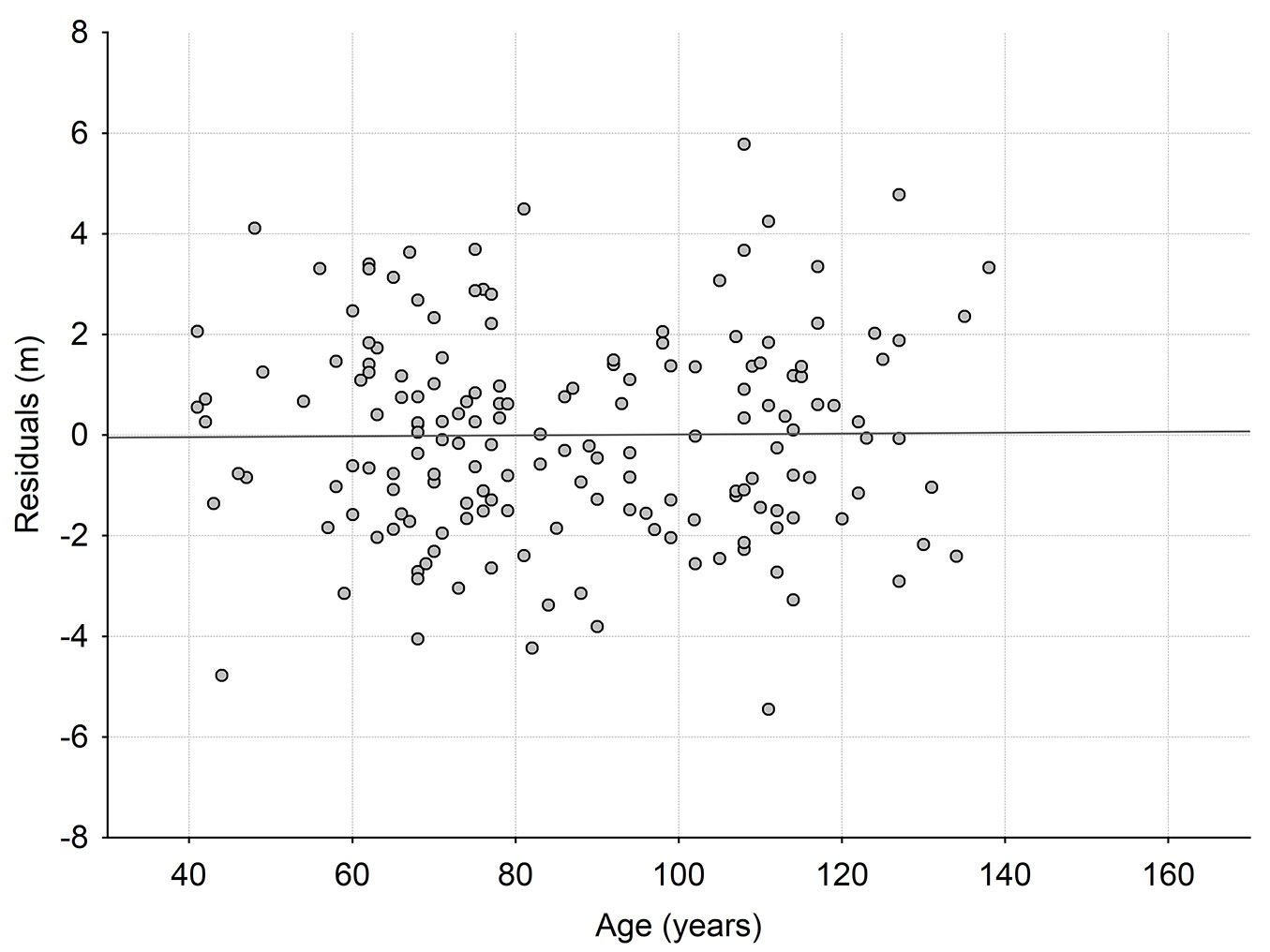

Lastly, the site index prediction GAM model for SIM (eqn. 5) as function of environmental factors was fitted (Tab. 1). Again, the validation of the SIM model was based on the analysis of the relationship between residuals of the site index prediction GAM model (Tab. 1) and stand age. In this case, no significant correlation was detected between the residuals of site index prediction model developed with the use of SIM and stand age (Fig. 3, Tab. 2).

Fig. 3 - Relationship between residual values (obs-pred) of site index prediction model based on local site index model SIM for Polish mountains ([41]) and stand ages.

Considering stand age in site index prediction model with SIM as the independent variable also showed no increase in the explained variance. As a result, in this case, there was no systematic error in site index estimation related to age of the stands (Fig. 3, Tab. 2), thus the site index is stable along the stand age.

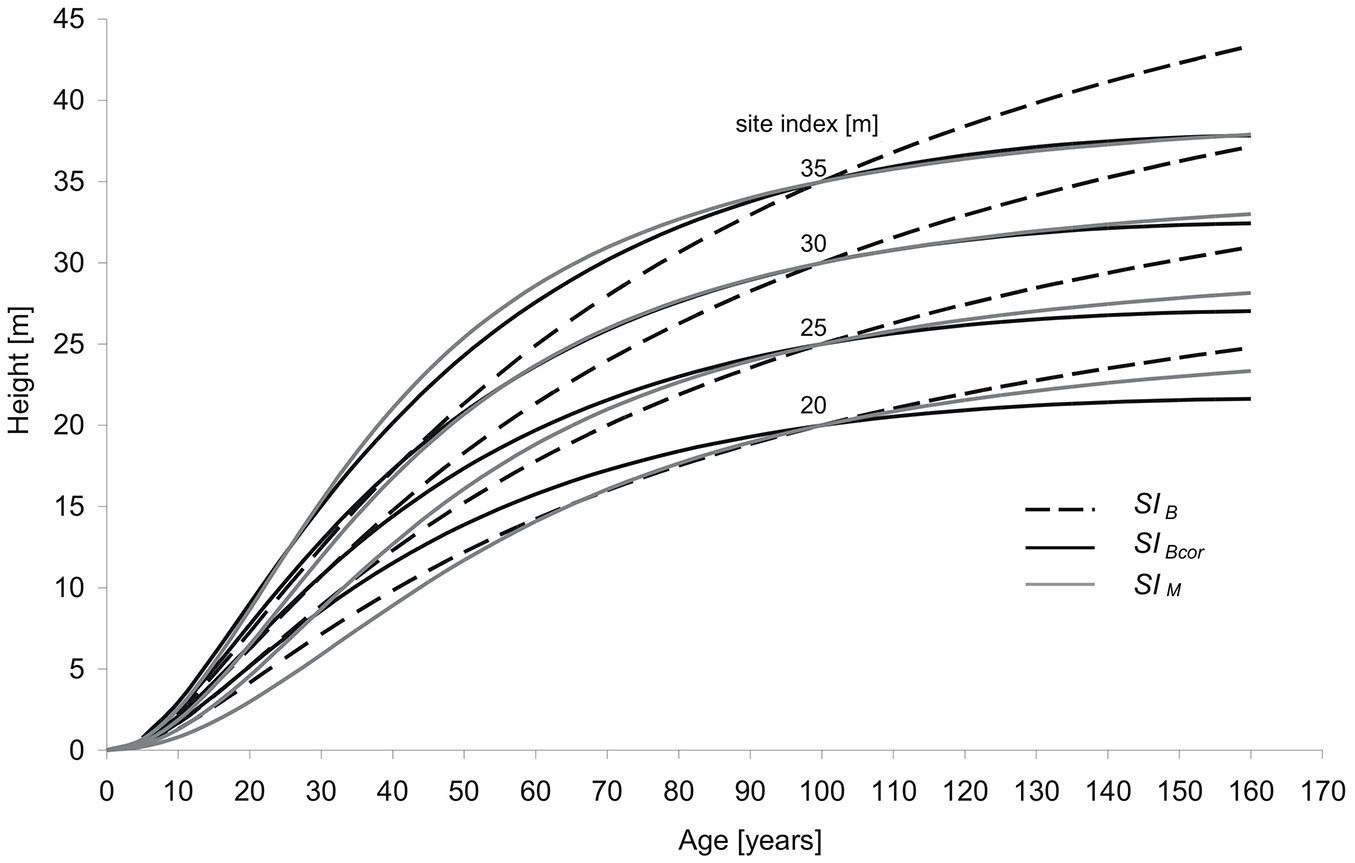

The example of temporary correction of SIB model to local conditions

The results of the analysis indicated a strong age trend in site index resulting from the use of the SIB model in local conditions. Therefore, the proposed correction procedure equation describing the dependence of expressed residuals of SIPM on stand age was used to adjust the height development patterns of the SIB model. Examples of the correction are graphically presented for individual SI curves 20m, 25m, 30m, 35m in Fig. 4. In general, in the case of medium and good sites showing a site index over 25m, there is close similarity between the corrected SIB and the local SIM site index models (Fig. 4). Only the least productive stands had large differences (Fig. 4).

Height increment analysis indicates that, in the case of SI model developed for local conditions of Polish mountains for stands up to 45 years old, the height growth rate is higher than that assumed in the model SIB, whereas for stands over 50 years the height growth rate is lower than expected by the validated model. Especially, large differences in site index curves are observed for the oldest stands (> 100 years - Fig. 4). The above mentioned differences are the reason of the overestimation of site index for younger stands and underestimation of site index for stands in ages older than base age (100 years).

Discussion

Inappropriateness of site index models manifested by age trend has been widely observed ([44], [46], [5], [42]). The existence of correlations between site index and stand age have been frequently reported and most often an age trend has been interpreted as driven by changes in site conditions ([18], [24], [8], [30], [49]). However, other important sources of site index model inappropriateness are reported, such as local differences in top height trajectories resulting from specific site conditions ([23]), genetic variability ([11], [1]) and inappropriate data, model or methods used in development of site index model ([14], [15], [20]).

Site index estimated on the basis of stand height and age is only an approximation of an unobservable site variable, which express the site conditions for given tree species. As a consequence of the aforementioned definition, it can be assumed that:

- Environmental drivers and the associated plant physiological response remain constant over the life of the stand, without changes in genetic structure, forest management practices or any other modifying growth factors. Given the same site conditions, site index values calculated for young stands should be equal to site index of older stands. Therefore, in such cases the site index curves describing change in height with age for young and old stands should be similar.

- In the case of deteriorated or improved site conditions (such as those caused by improved climatic conditions, CO2 fertilization or nitrogen deposition, genetic improvement, change in forest management practices or other factors influencing growth rate), younger stands may grow faster and therefore trajectories describing change in stand height with age for younger stands are different from those for older stands ([30], [49]). As the consequence of the change in site productivity over time, models describing change in stand height with age are not explicitly linked to site index. In such cases site index models should take into account time trend in site productivity in order to obtain comparable site indexes for sites characterized with comparable site productivity, irrespectively of the age of stand growing in a given location. Otherwise, the use of site index is restricted only to stands in a specific age range.

The proposed procedure assumes that the residuals from the SIPM describing the site index as the function of site properties should not be correlated with stand age. Site index prediction models were used in this case because direct correlation between the site index and stand age may also result from the irregularity in localization of stands of varying ages on different site conditions, which is commonly observed ([30]). It is particularly likely in mountainous areas, where stands at the highest altitudes under poorer site conditions are frequently older than stands at lower altitudes in richer sites. This irregularity results from the unequal accessibility to stands located at different altitudes and possibly from differences in the rotation age.

Most authors agree that observed age trend in site index estimates are the result of changing site conditions ([30], [32], [31], [48], [49]). However, in this paper more localized site index models developed for the Carpathians did not revealed correlations with the age of stands. Likely, this is caused by the local model built using data from trees growing under environmental changes. Moreover, a large component of the stem data used to develop the site index model comes from relatively young (60-70 years old) stands ([41]). Thus, most trees were grown under the ameliorating effect of nitrogen deposition, increased temperature and CO2 concentration, and this may result in marked changes of site conditions as compared with the early 1950s ([49]). Likewise, in lowland Scots pine stands in southern Poland ([42]), site indexes calculated using site index models developed for Poland ([10]) and Schwappach’s ([35]) yield tables indicated strong correlation between site index and the age of stands. However, after the use of site index model developed for local site conditions, substantial overestimation of site indexes for young stands disappeared ([42]).

Strong correlation between site index and age of stands was apparent only in the case of site index model SIB. We assume that the most probable cause of this is that this model was developed for the whole population of Norway spruce in Poland, including both for mountain and lowland sites. It could be expected that in mountain areas trees in young stands initially grow relatively faster than in older stands. Therefore, the use of site index models appropriate for lower elevations applied to high mountain forests may result in an age trend. Comparably different growth trajectories for high- and low-elevation stands were observed between subalpine fir, Engelmann spruce, lodgepole pine and black spruce in British Columbia ([25], [13], [29]). Evidence of different growth in mountain Norway spruce stands was also observed in Norway by Bøhler & Bernt-Håvar ([5]).

The most problematic issue with the proposed validation procedure is the difficult separation of the effect of change in site conditions from the effect of using inappropriate site index models on observed age trends in site indexes. However, regardless of the source of the site index age trends, the correlation between residuals of site index prediction models and the age of stands indicates inappropriate site index predictions, which makes the proposed approach useful in both cases. Moreover, both in the case of changing site productivity and inappropriate site index model, the usefulness of site index predictions is questionable.

Climate-based site index models may also represent an improved alternative, which take into account changes in site parameters such as temperature, precipitation, drought length, etc. ([7], [26]). However, both traditional site index models describing site index as the function of stand age and height, and site index models including climatic parameters as additional independent variables in the case of changing site conditions, gives the assessment of the site index dependent on the age of the stand.

Most of the recently published papers on forest productivity demonstrate the high probability of further changes in site conditions around the world ([16], [17], [3], [30]). Therefore, one of the most important aspect for forest management is to attain a reliable evaluation of site index models appropriateness and its correction to local growth conditions.

Conclusions

Age trends may result from inappropriateness of site index models, often driven by: (a) local differences in top height trajectories resulting from specific site conditions, forest management practice or genetic variability; (b) inappropriate model or methods used in the development of the site index model; and (c) changes in site conditions. Relationship between the residuals of site index prediction models describing site index as a function of environmental factors and age of the stands may be used for the validation and correction of site index models in forest inventory. The existence of a correlation between residuals of site index prediction models and the age of stands implies the occurrence of systematic errors in site index determination. Such model inadequacy results in the under-/overestimation of the height of the stand in base ages. The regression model describing the relationship between the residuals of site index prediction model and the age of the stand may be used to detect the age trend in site index model, and to make it more suitable to local site conditions.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Polish National Science Center, Grant NN-309-066939. JS acknowledges the support by the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, BC, Canada) and the University of Agriculture in Krakow (Poland).

References

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Wojciech Ochal

Department of Biometry and Forest Productivity, Faculty of Forestry, University of Agriculture in Krakow, Al. 29-listopada 46, 31-425 Krakow (Poland)

Integrated Remote Sensing Studio, Department of Forest Resources Management, Faculty of Forestry, University of British Columbia, 2424 Main Mall, BC V6T 1Z4, Vancouver (Canada)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Socha J, Coops NC, Ochal W (2016). Assessment of age bias in site index equations. iForest 9: 402-408. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1548-008

Academic Editor

Agostino Ferrara

Paper history

Received: Dec 30, 2014

Accepted: Dec 10, 2015

First online: Jan 11, 2016

Publication Date: Jun 01, 2016

Publication Time: 1.07 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2016

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 50534

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 42015

Abstract Page Views: 3262

PDF Downloads: 3942

Citation/Reference Downloads: 24

XML Downloads: 1291

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 3704

Overall contacts: 50534

Avg. contacts per week: 95.50

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2016): 19

Average cites per year: 1.90

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Potential impacts of regional climate change on site productivity of Larix olgensis plantations in northeast China

vol. 8, pp. 642-651 (online: 02 March 2015)

Research Articles

Relationship between environmental parameters and Pinus sylvestris L. site index in forest plantations in northern Spain acidic plateau

vol. 9, pp. 394-401 (online: 16 January 2016)

Research Articles

Site quality assessment of degraded Quercus frainetto stands in central Greece

vol. 8, pp. 53-58 (online: 12 May 2014)

Research Articles

Soil and forest productivity: a case study from Stone pine (Pinus pinea L.) stands in Calabria (southern Italy)

vol. 4, pp. 25-30 (online: 27 January 2011)

Research Articles

Seedling quality and short-term field performance of three Amazonian forest species as affected by site conditions

vol. 17, pp. 80-89 (online: 21 March 2024)

Research Articles

Scots pine’s capacity to adapt to climate change in hemi-boreal forests in relation to dominating tree increment and site condition

vol. 14, pp. 473-482 (online: 18 October 2021)

Research Articles

Developing a stand-based growth and yield model for Thuya (Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast) in Tunisia

vol. 9, pp. 79-88 (online: 23 June 2015)

Research Articles

Impact of climate change on radial growth of Siberian spruce and Scots pine in North-western Russia

vol. 1, pp. 13-21 (online: 28 February 2008)

Research Articles

Model-based assessment of ecological adaptations of three forest tree species growing in Italy and impact on carbon and water balance at national scale under current and future climate scenarios

vol. 5, pp. 235-246 (online: 24 October 2012)

Research Articles

The effect of the calculation method, plot size, and stand density on the accuracy of top height estimation in Norway spruce stands

vol. 10, pp. 498-505 (online: 12 April 2017)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword