The impacts of a wildfire on hunting demand: a case study of a Mediterranean ecosystem

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 8, Issue 1, Pages 95-100 (2015)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor0799-007

Published: May 12, 2014 - Copyright © 2015 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

The present study attempted to estimate the socioeconomic impacts on hunting demand caused by a 2006 wildfire on a typical Mediterranean ecosystem in Greece (Kassandra peninsula). A questionnaire administered to a sample of local hunters was used to test the hypothesis that the wildfire and the consequent hunting ban, which was used by the Greek Forest Service as a measure for wildlife protection, posed a significant impact on the demand of hunters for hunting licenses and hunting trips. Using questionnaires as a source of information it was assessed what these impacts meant for the economy, either on local, or national scale, by estimating the income elasticity of demand for hunting licenses in the area of Kassandra and the expenses for hunting excursions before and after wildfire. It was observed that hunters attempted to preserve their activity despite the excessive hunting restrictions. Implications for hunting management and policy decision making were examined.

Keywords

Elasticity of Demand, Hunters, Hunting Management, Wildfires, Greece

Introduction

An increasing interest in the socio-economic aspects related to wildfires is attested by Cortner et al. ([10]), Brunson & Tanaka ([9]) and reviewed by Stokowski ([46]). According to Moreira et al. ([31]) “socio- economic drivers have favored land cover changes contributing to increase fire hazard in the last decades”. The widespread abandonment of traditional land uses during the 20th century has led to the growth of extensive forests, woodlands and scrubs vegetation prone to wildfires, especially in the Mediterranean regions ([4]), contributing also to significant economic losses for the agricultural and livestock production ([29]).

Wildfires are considered as a major disturbance factor to Mediterranean ecosystems, affecting both biodiversity and human activities on forest land ([47]), impacting forest structure and landscape ([19]), causing changes in the taxonomic composition of insect communities ([25]), increasing or reducing populations of some bird and mammal species ([37], [39]), and provoking major impacts on soil gastropods ([8]). Quinn ([36]) discusses the direct and indirect impacts of wildfire to the wildlife. Barlow & Peres ([2]) found a decline in the fruit production and the abundance of species due to wildfires in a central Amazonian forest. On the other hand, Keith & Surrendi ([21]) found more snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) in burned areas one year after a wildfire. Similarly, an increase in lagomorphs populations after wild or prescribed fires has been reported ([37], [1]). Moreira et al. ([30]) suggest that in Mediterranean ecosystems wildfires can positively affect bird populations, or have little impact on winter visitors like woodcock.

Wildfires also influence human outdoor activities, such as hunting ([50]), which represents an important socioeconomic practice in the Mediterranean area ([28], [43], [44], [45]). About 2.5 million hunters live in areas affected by wildfires in the Mediterranean Europe ([13]). Although in Mediterranean ecosystems hunting is reckoned as an important activity, little information exists in the scientific literature on the impact of wildfires on hunting. In general, researches in recreational economics have focused on the effects of wildfires on the recreation demand ([11], [12], [5]), in particular hiking and biking ([23], [17], [18]).

In Greece hunting has a strong recreational character, and is usually practiced at a local level. However, post-wildfires hunting bans (2-5 years) issued by the Forest Service for wildlife protection may push hunters to move up to 300-500 km in order to find game species ([33], [34]). In Spain, post-wildfires hunting bans last from one to ten years according to Spanish law ([50]).

The goal of the present study is to estimate the impacts of a large wildfire occurred in 2006 in the Kassandra peninsula (north-western Greece) on local hunting activities. Our hypothesis was that hunting activity was negatively affected by the hunting ban issued after the aforementioned wildfire. We investigated the impact of the hunting ban on hunting demand using a socio-economical approach by comparing the following parameters before and after the wildfire: (a) the outdoor activities of hunters in the area; (b) the reduction of hunting licenses after the wildfire; (c) the number of hunting excursions; and (d) the traveling distance of hunters.

Methods

Study area

The study was carried out on the Kassandra peninsula of Chalkidiki’s Prefecture, Macedonia (Greece). Kassandra is a touristic and densely populated peninsula and numerous villages or small towns were threatened by the wildfire of August 2006. Total area is 374 km2 and the wildlife refuges where hunting is prohibited cover an area of 57.1 km2.

The study area was a typical Mediterranean landscape with Aleppo pine forests (Pinus halepensis), maquis and cultivated areas (mainly with cereals, legumes and olive groves - [48]). The area was affected by a wildfire on August 21st, 2006, just one day after the opening of the hunting period (Aug 20 - Feb 28). The wildfire burnt an area of 68.7 km2 in the center of the peninsula. Hunting was banned initially on the whole peninsula, then it was restricted to the burned area on Nov 25th, 2006. From the season 2008-2009, the ban was removed and hunting was allowed on the burnt area again.

The main quarry species in the area were hare (Lepus europaeus) and migratory birds: woodcock (Scolopax rusticola), quail (Coturnix coturnix), turtle dove (Streptopelia turtur), woodpigeon (Columba palumbus) and thrushes (Turdus spp.). The hunting period for the hare lasts from September 15 to January 10. Hunting system is “res publica”, i.e., the game become property of the hunter upon payment of an annual license. Furthermore, hunting in the area is allowed to visitors from other hunting clubs with a suitable license (regional or general).

Data collection

Data were collected through structured interviews conducted by telephone on October 2008. This survey methodology is commonly applied in socio-economic researches with the aim of examining citizens’ behavior ([26], [35], [40], [38]).

Licensed hunters of the Kassandra region were in total 512 on October 2008. Only local hunters were interviewed, since they constitute the majority in the region (few non-local hunters usually visit the area). A sample of 56 persons (10.94% of the total) was drawn from the alphabetic catalog of licensed hunters for the period 2008-2009, as provided by the Hunting Club of the Kassandra region. After choosing randomly the first hunter, every fifth person was called next ([14]). If the hunter was not available, the previous or the next one (alternately) in the catalog was called. To avoid biases, consanguinity relations were avoided (e.g., father-son). Similarly to previous researches ([45]), the response rate was 100%.

After a preliminary exploration of the collected data, eleven questionnaires were discarded as respondents were used to practice hunting out of the study area. This resulted in a total of 45 valid questionnaires, a number similar to that reported for analogous studies in the scientific literature ([41], [51]). Variables used for the statistical analysis are reported in Tab. 1.

Tab. 1 - List of variables used in the survey.

| Variable | Type | Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | Scale | - |

| Activities before wildfire | Nominal, multiple response | (i) Hunting; (ii) Training of hunting dogs; (iii) Plant collection; (iv) Outdoor training, walking; (v) Picnic; (vi) Others; (vii) Nothing |

| Activities after wildfire | Nominal, multiple response | (i) Hunting; (ii) Training of hunting dogs; (iii) Plant collection; (iv) Outdoor training, walking; (v) Picnic; (vi) Others; (vii) Nothing |

| Quarry species | Nominal, multiple response | (i) Hare; (ii) Wild boar; (iii) Birds with pointer dogs; (iv) Arboreal birds; (v) Waterfowl birds |

| Hunting license (HL) 2005-2006 | Nominal | (i) No HL; (ii) Local; (iii) Regional; (iv) General |

| Hunting license (HL) 2006-2007 | Nominal | (i) No HL; (ii) Local; (iii) Regional; (iv) General |

| Hunting license (HL) 2007-2008 | Nominal | (i) No HL; (ii) Local; (iii) Regional; (iv) General |

| Hunting license (HL) 2008-2009 | Nominal | (i) No HL; (ii) Local; (iii) Regional; (iv) General |

| Excursions (days/week) 2005-2006 | Scale | - |

| Excursions (days/week) 2006-2007 | Scale | - |

| Excursions (days/week) 2007-2008 | Scale | - |

| Travelling distance 2005-2006 (km/excursion) | Scale | - |

| Travelling distance 2006-2007 (km/excursion) | Scale | - |

| Travelling distance 2007-2008 (km/excursion) | Scale | - |

| Type of vehicle | Nominal | (i) Automobile; (ii) Pickup/Van/Light Truck (PVLT) |

| Reason for not issuing a hunting license after the forest wildfire |

Nominal | (i) Because of the forest wildfire; (ii) Other reasons; (iii) Not an adult yet |

| Distance from burnt area | Nominal | (i) Closer; (ii) Farther |

| Direction of residency (with regard to the burnt area) |

Nominal | (i) North; (ii) South; (iii) Sidelong |

Statistical analysis

Data were initially explored by means of descriptive statistics ([6]) in order to obtain some basic information about the sample. Departure from normal distribution of scale variables was verified by the non-parametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (α = 0.05). Multiple response analysis ([20]) was used for the analysis of the multiple response variables (see Tab. 1), while for the analysis of hunters’ activities before and after the wildfire, McNemar’s test for paired nominal dichotomous data ([15]) was applied.

Hunters’ behavior before and after the wildfire with regard of their license type was examined through the Marginal Homogeneity test, which is recommended for detecting response changes in categorical variables due to experimental interventions in before-and-after designs ([32]). Furthermore, a two-factor mixed factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measurements was applied ([15]), followed by the post-hoc Bonferroni’s comparison test, in order to reveal possible differences in the number of hunting excursions and in the overall traveling distance before and after the wildfire. Although a non-parametric analysis is more suitable in the case of small sample size, no analogous non-parametric method does exist for the parametric ANOVA mentioned above. Thus, data were prior checked for homogeneity of covariance by the Mauchly’s sphericity test: when such assumption was violated, the Greenhouse- Geisser correction was applied ([15]). All the statistical analyses were performed using the software package IBM SPSS® v.19.0 ([32]) with α = 0.05.

Economic analysis

The economic impact of the wildfire on hunting activities was assessed in two ways. Firstly, according to other environmental economical studies ([7], [24]), the income elasticity of demand for hunting licenses was estimated ([49], [27]) in order to test whether other reasons different from the wildfire (e.g., possible hunters’ income decreases) may have contributed to a possible post-fire decrease in the hunting demand.

Secondly, hunters’ expenditures before the wildfire and for the two subsequent years were compared. As most respondents were local hunters, we expected that the main costs influenced by the post-fire hunting ban were attributable to transportation ([43]), therefore only the vehicle operating costs were considered. Vehicles were divided in two large categories (1: Automobiles; 2: Pickup/Van/Light Trucks - Tab. 2) and their operating costs (in 2007 eurocents km-1) for fuel consumption, maintenance/repairs, tires and depreciation were calculated. Moreover, since the length of the hunting period is different depending on the game species (15 weeks for hares, 25 weeks for birds), the comparison was carried out independently on the following two categories: (i) exclusive hare hunters; (ii) other hunters (including those hunting on hare and other species). The above cost-analysis approach is fairly common in the recreational economics literature ([22]).

Tab. 2 - Vehicle operating costs (2007 eurocents km-1 per vehicle). Source: adapted from Barnes & Langworthy ([3]).

| Cost category | Automobile | % of total cost |

Pickup/Van/ Light Truck |

% of total cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel | 5.21 | 47.1 | 7.9 | 60.3 |

| Maintenace/Repairs | 1.9 | 17.2 | 1.59 | 12.1 |

| Tires | 0.5 | 4.5 | 0.45 | 3.4 |

| Depreciation | 3.44 | 31.1 | 3.17 | 24.2 |

| Total | 10.42 | - | 13.74 | - |

Results and Discussion

Mean age of respondents was 51.7 years (standard deviation = 15.5, min = 21, max = 79, median = 49), with no significant departure from normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov 2-tailed test: D = 0.102, p = 0.69). The most preferred quarry species were hare (64.4%), followed by birds, mainly woodcock (42.2 %) and arboreal birds (15.6 %).

Results of the survey carried out in this study are reported in Tab. 3. A significant difference in hunting activity within the burnt area before and after the wildfire was detected (McNemar test for paired nominal data: p<0.05). Indeed, only 6.1% of the respondents went on with hunting after the wildfire of August 2006, while 55% just gave up. Most of the other outdoor activities showed a consistent though non-significant reduction, and some completely disappeared in the post-fire period (e.g., picnicking). Hasanagas et al. ([16]) showed that most human activities on the burnt area were restored two years after the wildfire.

Tab. 3 - Outdoor activities of the respondents in the burnt area before and after wildfire (in %). (a): refers to the beginning of 2008-2009 period, when hunting was permitted in burnt area. (*): p<0.05; (ns): not significant.

| Outdoor Activities | Wildfire | McNemar test p-value |

Observed MH statistic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before (%) |

After (%) |

2005-06 vs. 2006-07 |

2005-06 vs. 2006-07 |

2005-06 vs. 2006-07 |

||

| Hunting | 44.4 | 24.4 (a) | 0.022* | - | - | - |

| Training of hunting dogs | 17.8 | 11.1 | 0.453ns | - | - | - |

| Plant collection | 8.9 | 2.2 | 0.25 ns | - | - | - |

| Outdoor training, walking | 15.6 | 8.9 | 0.25 ns | - | - | - |

| Picnic | 4.4 | 0 | 0.5 ns | - | - | - |

| Other | 4.4 | 4.4 | 1 ns | - | - | - |

| Nothing | 48.9 | 64.4 | 0.065ns | - | - | - |

| Hunting licenses | - | - | - | 13.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 |

| - | - | - | 0.827ns | 0.739ns | 0.739ns | |

Hunting licenses

The mean number of hunting licenses in three hunting periods before the wildfire was 543, and decreased to 470, 495 and 523 for the 2006-2007, 2007-2008 and 2008-2009 hunting seasons, respectively. No statistically significant differences were found between the hunting periods analyzed after the marginal homogeneity (MH) test (Tab. 3). Some 13.6% of the respondents did not renew their hunting license for the 2006-2007 hunting season, and 11.1% acknowledged it as due to the hunting ban. On the other hand, the percentage of respondents with a new hunting license issued for the first time after the wildfire was 4.5%. The fairly low reduction of the number of licenses in the burnt area may be partly explained by the fact that the wildfire occurred one day after the opening of the hunting period, when many respondents had already renewed their license.

Hunting excursions

The total number of excursions before wildfire was estimated at 20 675 per hunting period; after wildfire it decreased to 6 590 for the 2006-2007 hunting season and to 16 697 for the 2007-2008 season. Such reduction was due by: (i) the decrease of the number of hunters; (ii) the shortening of the 2006-2007 hunting period; and (iii) the decrease of the number of excursions per week. Significant differences within-subjects in the variable “excursions per week” were detected after Greenhouse-Geisser test (F[1.7, 59.9] = 4.97, p = 0.014). The interaction between the variable “mean number of excursions” and the factor “direction of residency” was also significant (Greenhouse-Geisser: F[3.4, 59.9] = 3.05, p = 0.03). Significant differences in the mean number of excursions were detected between the 2005-2006 and 2007-2008 hunting periods (mean difference = 0.9, p = 0.007) after Bonferroni tests. Unexpectedly, such difference was not significant for the first period after wildfire (2005-2006 vs. 2006-2007, p = 0.135). This might be due to the shortened hunting period in 2006-2007; thus apparently hunters took more excursions per week to compensate the shortened duration.

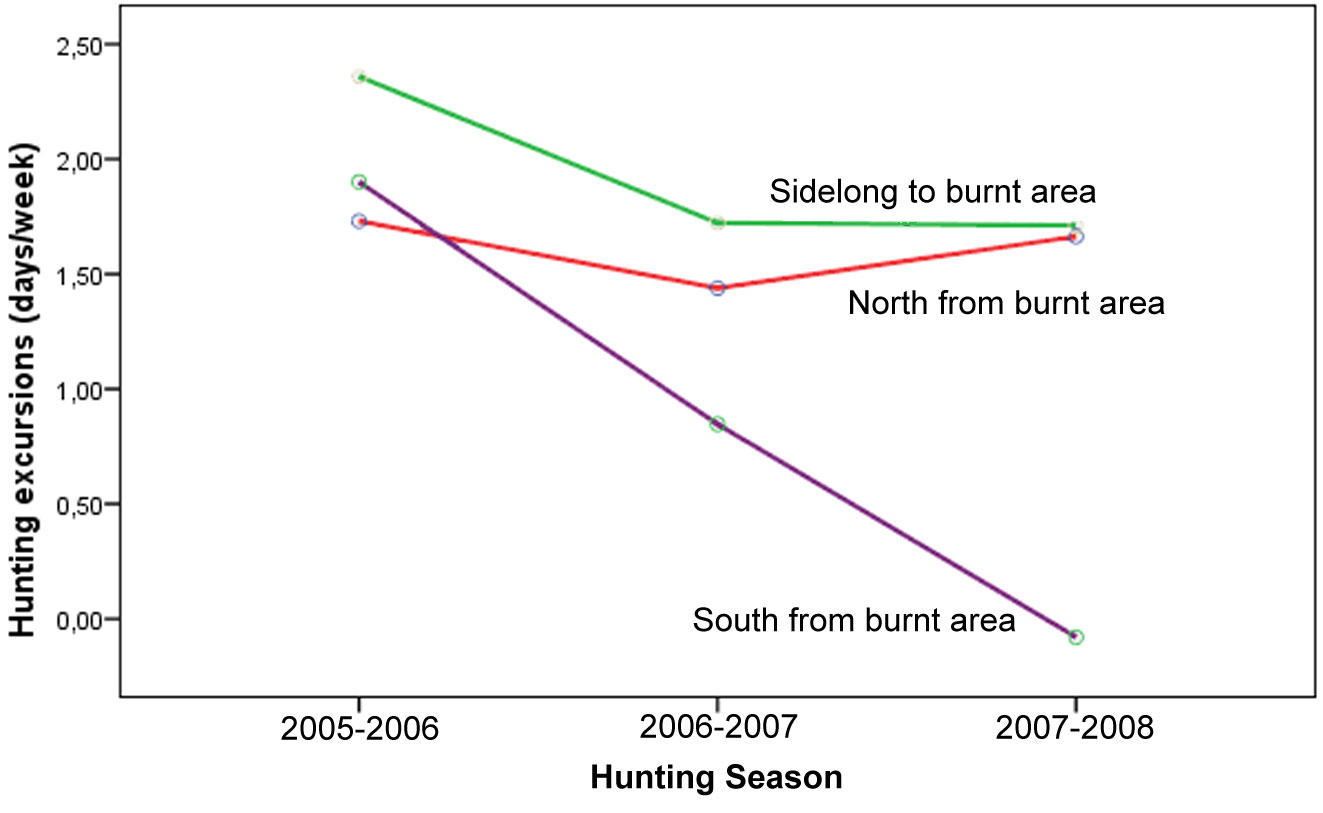

The analysis of the interactions among the variables analyzed revealed a significant interaction between the number of excursions and the location (direction) of residency for respondents living south from the burnt area (F = 5.98, p = 0.004 - Fig. 1), likely due to the longer distance from suitable hunting areas.

Fig. 1 - Trend of mean hunting excursions per hunter before and after the wildfire (2006) with regard to the direction of residency from the burnt area.

Travelling distance

The application of the ANOVA to the dependent variable “travelling distance” (TD) did not reveal any significant differences, neither within subjects nor between distance and direction from the burnt area (Mauhly’s W = 0.87, p = 0.18; Fdistance [2, 52] = 0.068, p = 0.93). However, an increase in the traveling distances after the wildfire was observed (TD2005-2006 = 25.4 ± 35.5 km; TD2006-2007 = 40.5 ± 76.8 km; TD2007-2008 = 32.0 ± 49.8 km).

Analysis of income elasticity

Tab. 4 summarizes the main characteristics of the hunting activity for hare and other hunters before the wildfire and in the two subsequent years. From 2005 to 2006 the decrease of hunting licenses was equal to 13.5 %. Considering the Gross Domestic Product per capita for the same period in Greece (17 400 € in 2005, 18 700 € in 2006, and 19 900 € in 2007), the income elasticity of demand (IED) for hunting licenses was calculated. It was reasonably assumed here that hunters (200 000 people, about 2% of the total) are a representative sample of the total Greek population, and that local GDP does not differ from the national one (no GDP data were available for local administrations).

Tab. 4 - Main characteristics of the hunting activity before and after the occurrence of the wildfire in the studied area. (a): Mean average of hunting licenses of the last three years before the wildfire. (HH): hare hunters; (OH): other hunters.

| Year | Number of hunters (licenses) |

Traveling distance (km excursion-1 per hunter) |

Excursions week-1 per hunter |

Hunting period (weeks) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | HH | OH | HH | OH | HH | OH | HH | OH | |

| before wildfire(a) | 543 | 217 | 326 | 44.25 | 28.05 | 1.97 | 1.75 | 15 | 25 |

| 2006-2007 (after wildfire) |

470 | 188 | 282 | 87.75 | 15.25 | 1.78 | 1.25 | 6 | 13 |

| 2007-2008 (after wildfire) |

495 | 198 | 307 | 76.25 | 25.34 | 2.03 | 1.39 | 15 | 25 |

In 2005 and 2006 the IED is below zero for all the categories of hunters (IED05-06→06-07 = -1.8). This means that, contrary to the expectations, the number of hunting licenses issued in the year after the wildfire was lower even though the respondents’ income was higher. Such evidence suggests the hypothesis that the reduction of hunting licenses issued for the burnt area in 2006 was only due the wildfire.

Analysis of car expenses

Tab. 5 shows the total traveling distances of the two categories of hunters with the two class of vehicles considered for the three hunting periods analyzed. Some 81.2% of hare hunters of Kassandra used pick up/van/ light trucks and 18.8% used automobiles, while for the category “other hunters” such percentages were 79.2% and 20.8%, respectively.

Tab. 5 - Total traveling distances in km. (PVLT): Pickup/Van/Light Truck; (A): automobile.

| Year | Total | Hare hunters | Other hunters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVLT | A | PVLT | A | ||

| before wildfire | 683 809 | 230 402 | 53 344 | 316 850 | 83 213 |

| 2006-07 (after wildfire) |

246 069 | 143 064 | 33 123 | 55 347 | 14 535 |

| 2007-08 (after wildfire) |

730 051 | 373 291 | 86 427 | 214 104 | 56 229 |

A reduction in the total expenditures (-35 %) was also observed for the first hunting period after the wildfire (Tab. 6) and this is thought to be related to the hunting ban. However, in the second year after the wildfire a large increase in total expenditures (+90.23 %) was observed, which appears to be due to the greater traveling distances as compared with the previous year. The increase of expenditures was lower for hare hunters than for other hunters, as hare hunters are used to hunt closer to their home places ([43], [33]).

Tab. 6 - Total vehicle operating costs per hunter type and per vehicle type (in €). (PVLT): Pickup/Van/Light Truck; (A): automobile.

| Cost category | 2005-2006 (before fire) | 2006-2007 (after fire) | 2007-2008 (after fire) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hare hunters | Other hunters | Hare hunters | Other hunters | Hare hunters | Other hunters | |||||||

| PVLT | A | PVLT | A | PVLT | A | PVLT | A | PVLT | A | PVLT | A | |

| Fuel | 18201.77 | 2779.24 | 2503.12 | 4335.40 | 11302.10 | 1725.73 | 4372.45 | 757.31 | 29490.04 | 4502.85 | 16914.22 | 2929.55 |

| Maintenace/ Repairs | 4377.64 | 848.18 | 602.02 | 1323.09 | 2718.23 | 526.66 | 1051.60 | 231.12 | 7092.54 | 1374.19 | 4067.98 | 894.05 |

| Tires | 1152.01 | 240.05 | 158.43 | 374.46 | 715.32 | 149.06 | 276.74 | 65.41 | 1866.46 | 388.92 | 1070.52 | 253.03 |

| Depreciation | 7925.83 | 1691.02 | 1089.96 | 2637.86 | 4921.42 | 1050.01 | 1903.95 | 460.78 | 12841.23 | 2739.74 | 7365.18 | 1782.47 |

| Totals | 31657.25 | 5558.48 | 4353.52 | 8670.81 | 19657.08 | 3451.45 | 7604.74 | 1514.62 | 51290.28 | 9005.71 | 29417.90 | 5859.10 |

| 37215.73 | 13024.33 | 23108.53 | 9119.36 | 60295.99 | 35277.00 | |||||||

| 50240.06 | 32227.89 | 95572.99 | ||||||||||

Conclusions

All outdoor activities in the Kassandra peninsula showed a reduction after the large wildfire occurred in the August 2006 ([5]); however, hunting was found the only activity to be significantly reduced. After the wildfire, a hunting ban was initially issued over the whole Kassandra’s peninsula, then it was limited to the actual burnt area for the subsequent two years. Nonetheless, one year after the wildfire the hare population was higher in burnt area than in nearby non-burnt areas and vegetation regeneration was adequate to provide cover and food to game species ([42]).

The aformentioned hunting restrictions in the studied area had several important socioeconomic consequences. First, a reduction of the number of licenses at the local hunting club was recorded (13.5% and 8.8% for the first and second hunting periods, respectively), even though hunters’ income increased in the same period. The second consequence was the reduction of hunting excursions, especially for hunters living south of burnt area for whom it was difficult to travel out of the banned areas. The third consequence for local hunters was the increase in the traveling distance, mainly in the second hunting period after the wildfire, leading to a strong increase in the vehicle operating costs in the same period (+90.23%). As a result, the lack of hunting areas available in the Kassandra peninsula for the period studied had several impacts like: (i) a higher hunting pressure in allowed areas close to the area interested by the ban; (ii) higher carbon emissions related to the increased distance traveled by hunters ([33]); (iii) relevant economic losses for hunters and local economy. As for the latter point, we calculated that the hunting ban for the period 2007-2008 (one year after wildfire) implied approximately 45 332 € of additional expenses for hunters, mainly due to the operating costs of vehicles. As an alternative, such money could have been recovered (at least in part) through a special license issued for hunting in the burnt areas, and used as a financial support of post-fire management of forest ecosystems and wildlife conservation, such as habitat improvements with proper plantings and wildlife warding.

Our results highlights the lack of integrated managing strategies for areas affected by wildfires in Mediterranean ecosystems. Indeed, the assessments of impacts of wildfires and their consequences (including hunting bans) on local economy should be conducted using an integrated environmental and socio-economic approach and supported by multidisciplinary experts, advisory information and monitoring.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the hunters of Kassandra’s Hunting Club and Apostolos Kastoris for his assistance in the data collection.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Laboratory of Forest Economics, Faculty of Forestry and Natural Environment, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GR-54124 Thessaloniki (Greece)

Research Division, Hunting Federation of Macedonia and Thrace, Ethnikis Antistaseos 173-175, GR-55134 Thessaloniki (Greece)

Laboratory of Wildlife, Department of Forestry and Management of Natural Environment, Technological Educational Institute of Thessaly, Mavromichali str., GR-43100 Karditsa (Greece)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Papaspyropoulos KG, Sokos CK, Birtsas PK (2015). The impacts of a wildfire on hunting demand: a case study of a Mediterranean ecosystem. iForest 8: 95-100. - doi: 10.3832/ifor0799-007

Academic Editor

Francesco Ripullone

Paper history

Received: Sep 25, 2012

Accepted: Oct 28, 2013

First online: May 12, 2014

Publication Date: Feb 02, 2015

Publication Time: 6.53 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2015

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 51633

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 43368

Abstract Page Views: 2924

PDF Downloads: 3967

Citation/Reference Downloads: 23

XML Downloads: 1351

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 4309

Overall contacts: 51633

Avg. contacts per week: 83.88

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

(No citations were found up to date. Please come back later)

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Perspectives of the forest workers in Greece

vol. 3, pp. 118-123 (online: 27 September 2010)

Research Articles

Assessing the performance of MODIS and VIIRS active fire products in the monitoring of wildfires: a case study in Turkey

vol. 15, pp. 85-94 (online: 19 March 2022)

Research Articles

Fire occurrence zoning from local to global scale in the European Mediterranean basin: implications for multi-scale fire management and policy

vol. 9, pp. 195-204 (online: 12 November 2015)

Research Articles

Post-fire recovery of Abies cephalonica forest communities: the case of Mt Parnitha National Park, Attica, Greece

vol. 11, pp. 757-764 (online: 15 November 2018)

Research Articles

First results on early post-fire succession in an Abies cephalonica forest (Parnitha National Park, Greece)

vol. 5, pp. 6-12 (online: 06 February 2012)

Research Articles

Indicators for the assessment and certification of cork oak management sustainability in Italy

vol. 11, pp. 668-674 (online: 04 October 2018)

Review Papers

Payment for forest environmental services: a meta-analysis of successful elements

vol. 6, pp. 141-149 (online: 08 April 2013)

Research Articles

Payments for forest environmental services: organisational models and related experiences in Italy

vol. 2, pp. 133-139 (online: 30 July 2009)

Research Articles

Impact of management practices on habitat use by birds in exotic tree plantations in northeastern Argentina

vol. 19, pp. 38-44 (online: 06 February 2026)

Research Articles

Drought effects on the floristic differentiation of Greek fir forests in the mountains of central Greece

vol. 8, pp. 786-797 (online: 08 April 2015)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword