Naturally regenerated English oak (Quercus robur L.) stands on abandoned agricultural lands in Rilate valley (Piedmont Region, NW Italy)

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 4, Issue 1, Pages 31-37 (2011)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor0560-004

Published: Jan 27, 2011 - Copyright © 2011 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

The present study was carried out in 14 sites located in Rilate valley, a hilly area in the south-east Piedmont (NW Italy) within the Monferrato district. Sites were selected where naturally regenerated forest communities are developing on abandoned crop lands. Altitude ranges from 190 to 240 m a.s.l., while the abandonment period varied from 1 to 50 years at the time of the surveys (year 2007). The presence of younger stands (i.e., stands with age < 12 yrs) demonstrates a rapid invasion of abandoned farmlands by forest communities dominated by English oak mixed with other hardwoods, such as wild cherry and common elm. Observations conducted in older stands (i.e., stands with age ranging between 20 and 50 yrs) confirm the ability of English oak to generate well structured woodlands in the study area. In these environmental conditions previous cropping and exposure seem to play a significant influence on stand characteristics. Other noble hardwoods, such as wild cherry and common elm, are frequently associated with the oak. These stands showed a mean annual increment varying from 4 to 6 m3 ha-1 year-1 at the age of 45-50 yrs. At the present, black locust is only sporadic in the uppermost canopy layer and generally confined in the understory. The rapid colonization by Q. robur is favoured by the presence of adult oak trees in the field edges, providing abundant acorns efficiently dispersed by small rodents and birds. Oak stands observed in this study are worthy of notice in the light of the current decline of many adult oak communities in northern Italy, as well as for their potential to produce lumber and veneer logs. Therefore, these stands should be preserved avoiding coppicing or other irrational cuts. Further studies would be needed to analyze the contribution of soil characteristics to the colonization processes.

Keywords

Quercus robur, Abandoned croplands, Oak stands, Piedmont, Rilate valley

Introduction

Over the centuries the acreage of Italian forests was markedly reduced to make room for crops, and forest vegetation was gradually confined in less favourable sites. Since the early decades of the XX century, many croplands were abandoned especially in mountainous and hilly areas, allowing secondary succession to take place and forest vegetation establishment ([15]). These processes generally involve the indigenous pioneer species. A typical case already studied by several authors in Italy are the broadleaf stands dominated by sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) and European ash (Fraxinus excelsior), colonizing abandoned croplands and grazing areas along the Alps ([7], [16], [8], [6], [18]). So far, less studied are the English oak (Quercus robur) stands developing on former croplands in the south-east of Piedmont (NW Italy), where a progressive abandonment of agricultural lands took place since the middle of the last century, particularly in the hilly areas. This phenomenon is important in relation to the widespread decline occurring in many adult oak communities in northern Italy ([17], [21], [1]) that also affects natural regeneration ([19]). In many cases, the development of oak stands is also disturbed by invasive woody species such as black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) that is naturalized and widespread in plane and hilly areas of the northern Italy and can exert a strong competition with oaks and other indigenous hardwoods. The present study aims to describe and analyze English oak stands naturally regenerated on abandoned croplands in a hilly area located in the south-east of the Piedmont Region.

Materials and methods

The study area

The research was conducted in the Rilate valley (44°58’ N, 8°08’ E) in the province of Asti (Monferrato district). The valley encompasses a vast area of approximately 106 km2 that extends from the outskirts of the city of Asti to the neighbouring municipalities. The valley line is rather large and easily cultivable and it is surrounded by several hills with altitudes ranging from 140 to 300 m a.s.l., where farming is now strongly declining. The average annual rainfall is about 700 mm with two equinoctial peaks. The average annual temperature is 12.6 °C and the mean January and July temperatures are 1.5 and 23.1 °C, respectively. Soils are mainly Entisols ([11]) derived from sediment deposits attributable to the group of Astiane sands; they are deep, with low developed horizons along the profile. Soil reaction varies from alkaline to sub-alkaline and texture from loam to silty loam.

Field sampling and data processing

A total of 14 sites where forest communities are establishing on former agricultural lands were selected within the study area (Tab. 1). Altitude ranges from 190 to 240 m a.s.l. and the timespan since abandonment varied from 1 to 50 years at the time of the surveys (year 2007). The previous crop was mainly vineyard or poplar and hazel plantations. The abandonment was frequently preceded by a period of time during which cultivation practices have been progressively reduced. The year of complete abandonment of farming activities has been deduced through interviews with owners or with other local residents.

Tab. 1 - Sites considered in the study.

| Site ID |

Latitude / Longitude |

Site name | Altitude (m a.s.l.) |

Exposure | Average slope (%) |

Previous crop |

Years from abandonment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44°57’58“N 08°08’04” E |

Mombarone | 230 | SW | 40 | Hazel plantation | 1 |

| 2 | 44°58’07“N 08°08’06” E |

Mombarone | 230 | SE | 40 | Vineyard | 2 |

| 3 | 44°57’55“N 08°08’02” E |

Mombarone | 210 | SW | 35 | Hazel plantation | 5 |

| 4 | 44°57’55"N 08°08’02" E |

Mombarone | 200 | SW | 25 | Hazel plantation | 5 |

| 5 | 44°57’58“N 08°08’01” E |

Mombarone | 220 | SW | 20 | Poplar plantation | 9 |

| 6 | 44°57’02“N 08°09’52” E |

Moncarantino Salice Verde | 250 | SW | 20 | Poplar plantation | 10 |

| 7 | 44°58’13“N 08°07’48” E |

Mombarone | 220 | NW | 25 | Poplar plantation | 12 |

| 8 | 44°57’50“N 08°08’01” E |

Mombarone | 190 | SW | 30 | Vineyard | 20 |

| 9 | 44°57’01“N 08°09’52” E |

Moncarantino Salice Verde | 220 | SW | 45 | Poplar plantation | 25 |

| 10 | 44°58’28“N 08°08’10” E |

Mombarone Casegrotta | 230 | SE | 30 | Vineyard | 35 |

| 11 | 44°57’57“N 08°07’56” E |

Mombarone | 210 | W | 35 | vineyard | 40 |

| 12 | 44°57’03“N 08°09’50” E |

Moncarantino Salice Verde | 240 | SW | 30 | Vineyard | 45 |

| 13 | 44°56’49“N 08°07’04” E |

Serravalle Sanna | 190 | SE | 15 | Vineyard | 45 |

| 14 | 44°56’40“N 08°07’04” E |

Bricco Carlevaro | 240 | S | 25 | Vineyard | 50 |

In stands aged 12 years or less, 8 plots of 2 x 2 m2 (site 1) or 7 plots of 4 x 4 m2 (sites 2 to 7) in size were delimited on the ground surface along a transect positioned in the middle of the stand in order to minimize the side effect. Inside the plots the height (h) and the species of all woody plantlets with h > 10 cm were recorded.

In each stand older than 12 years (sites 8 to 14) a plot of 50 x 20 m2 in size was delimited, with the longest side placed along the contour lines; it was always positioned in the middle of the stand to minimize side effects. For all trees with diameter at breast height (dbh) ≥ 7.5 cm falling within the plots, the following parameters were recorded:

- species;

- dbh;

- total height;

- height at the insertion of the crown;

- diameter of the crown measured along two orthogonal directions;

- Cartesian co-ordinates.

Within a sub-plot of 4 x 20 m2 in size placed along the central portion of the main plots, saplings with dbh < 7.5 cm and seedlings with height ≥ 10 cm and < 130 cm were counted separately for the different species.

For each stand older than 12 years the Square Mean Diameter (SMD), the diameter distribution, the height curve, as well as the total basal area and the standing volume were calculated. The latter was determined using the volume tables of the Italian National Forest Inventory ([3]). All parameters were reported per hectar after the plot size correction for slope. These stands were also graphically represented through the Stand Visualization System (SVS) software ([13]).

Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed for the younger (age ≤ 12 yr.) and older (age > 12 yr.) stands separately, using the software SPSS 16.0 for Windows®. The following variables were included in the analyses:

- stands with age ≤ 12 yr: altitude (m.a.s.l.), slope (%), years from abandonment; plant density (n ha-1); mean height (cm); percentage of oak plantlets (%); percentage of cherry plantlets (%); percentage of elm plantlets (%); percentage of hazel plantlets (%); percentage of plantlets belonging to the “other species” (%);

- stands with age > 12 yr: altitude (m.a.s.l.); slope (%); years from abandonment; plant density (n ha-1); SMD (cm); percentage of oak plantlets (%); percentage of cherry plantlets (%); percentage of black locust plantlets (%); percentage of plantlets belonging to the “other species” (%); basal area (m2 ha-1); standing volume (m3 ha-1); sapling and seedling density (n ha-1).

Results and discussion

Tab. 2 shows the results of surveys carried out in stands with youngest age among those considered. The total number of individuals per hectare was very variable, with a maximum of about 13 400 (site 3) and a minimum of about 3 750 (site 6). In all cases oak is the most frequent species, with a maximum of 92.1 and 88. 9% of all individuals surveyed in site 1 and 2, respectively. Only in site 5 oak seedlings are less than 50% of the total amount. Other species frequent in many of the examined stands are wild cherry (Prunus avium), common elm (Ulmus campestris), hazel (Corylus avellana) and hawthorn (Crataegus spp.). In these early stages of colonization black locust plantlets are infrequent. The mean height reached by oak seedlings is often less than in other species, but generally it increases regularly with timespan since complete land abandonment. In stand 5 both oak and cherry showed a particularly fast growth, probably due to the specific site conditions.

Tab. 2 - Plant density (n ha-1) and mean height (H) ± standard deviation in sites with age of abandonment ≤ 12 yrs.

| Site ID |

Species | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English oak | Wild cherry | Common elm | Hazel | Other species | Total | |||||||

| n ha-1 | H (cm) |

n ha-1 | H (cm) |

n ha-1 | H (cm) |

n ha-1 | H (cm) |

n ha-1 | H (cm) |

n ha-1 | H (cm) |

|

| 1 | 10154 | 19.7 ± 7.9 | 580 | 35.5 ±10.6 | - | - | 290 | 21.0 ± 5.7 | - | - | 11024 | 20.3 ± 8.5 |

| 2 | 4062 | 58.6 ± 42.1 | - | - | 508 | 30.6 ± 21.0 | - | - | - | - | 4570 | 55.0 ± 41.2 |

| 3 | 7247 | 75.1 ± 67.1 | 758 | 131.5 ± 80.6 | 2107 | 113.2 ± 49.8 | 2107 | 109.8 ± 57.6 | 1180 | 56.9 ± 78.5 | 13399 | 78.1 ± 68.6 |

| 4 | 5978 | 85.3 ± 54.4 | - | - | 780 | 129.8 ± 61.4 | 3639 | 61.4 ± 53.3 | 1040 | 150.8 ± 76.1 | 11437 | 87.1 ± 62.1 |

| 5 | 4750 | 190.2 ± 105.9 | 4214 | 181.2 ± 88.3 | 536 | 38.3 ± 16.9 | 1839 | 145.8 ± 68.7 | 1149 | 170.5 ± 87.8 | 12488 | 172.4 ± 95.6 |

| 6 | 2605 | 102.8 ± 93.5 | 460 | 76.3 ± 139.5 | 77 | 25.5 ± 3.5 | - | - | 613 | 228.9 ±135.4 | 3755 | 131.1 ± 116.9 |

| 7 | 3866 | 104.8 ± 85.8 | 1061 | 144.4 ± 62.3 | 152 | 100.0 ± 84.9 | 758 | 125.5 ± 62.3 | 152 | 108.5 ± 82.7 | 5989 | 114.4 ± 70.8 |

The results show a very rapid colonization of abandoned fields by forest vegetation and a strong pioneering attitude of English oak in the early stage of the secondary succession. A rapid colonization of former cropland by oak was observed in the eastern Netherlands by Smit & Olff ([20]) who noted that this process is linked to the availability of seed in neighbouring areas. In the present study the establishment of forest vegetation probably has already started during the period of reduced cultural activities before the complete abandonment. It is favoured by the adult oak specimens traditionally left by the farmers at the field edges, as well as the dispersal of acorns carried out by animals such as wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus) and Eurasian jay (Garrulus glandarius) which are considered very active in seed predation and dispersal in many European oak stands ([12], [5]). The abandonment of agricultural practices can also increase populations of small mammals ([9], [4]). Among the other native hardwoods, wild cherry and common elm show the greatest pioneering attitudes in the considered sites. The diffusion of wild cherry can be favoured by the root-sprouting ability typical of this species. On the contrary, black locust exhibits a low invasive potential in the early stages of stand development, possibly due to the low frequency of this species in the adjacent fields and the rapid soil covering by other woody species.

Tab. 3, Tab. 4 and Tab. 5 summarize the results of surveys conducted in stands older than 12 years. Also in these stands English oak was the dominant species in terms of relative abundance (Tab. 3), as well as basal area and standing volume (Tab. 4). In stands with age equal or higher then 40 years, i.e., sites 11, 12, 13 and 14, the calculated volume of oak trees was 121.11, 236.84, 264.66 and 203.51 m3 ha-1, respectively (Tab. 4), corresponding to a percentage of total stand volume varying from 80.6 to 98.8%. Among the other tree species, the most frequent are wild cherry and common elm. Black locust is fairly frequent only in plot 8, where it reaches a volume of 28.08 m3 ha-1, while it is sporadic or absent in all other stands.

Tab. 3 - Plant density (n ha-1) and Square Mean Diameter (SMD) in sites with age of abandonment > 12 yrs.

| Site ID |

Species | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English oak | Wild cherry | Common elm | Black locust | Other species | Total | |||||||

| n ha-1 | SMD (cm) | n ha-1 | SMD (cm) | n ha-1 | SMD (cm) | n ha-1 | SMD (cm) | n ha-1 | SMD (cm) | n ha-1 | SMD (cm) | |

| 8 | 699 | 12.6 | - | - | 201 | 12.4 | 220 | 13.0 | 96 | 12.8 | 1216 | 12.6 |

| 9 | 629 | 15.9 | 9 | 10.0 | 36 | 14.4 | - | - | - | - | 674 | 15.8 |

| 10 | 393 | 16.4 | 29 | 10.0 | 306 | 11.8 | 48 | 11.2 | 57 | 22.1 | 833 | 15.5 |

| 11 | 528 | 17.2 | 245 | 14.4 | 113 | 11.7 | - | - | 28 | 10.0 | 914 | 15.5 |

| 12 | 623 | 22.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 77 | 9.4 | 700 | 21.0 |

| 13 | 781 | 20.1 | - | - | 30 | 10.0 | - | - | 10 | 10.0 | 821 | 19.8 |

| 14 | 524 | 22.6 | 29 | 11.9 | 10 | 10.0 | 10 | 25.0 | - | - | 573 | 22.1 |

Tab. 4 - Basal area (G, in m2 ha-1) and standing volume (V, in m3 ha-1) in sites with age of abandonment > 12 yrs.

| Site ID |

Species | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English oak | Wild cherry | Common elm | Black locust | Other species | Total | |||||||

| G | V | G | V | G | V | G | V | G | V | G | V | |

| 8 | 8.68 | 54.84 | - | - | 2.42 | 13.85 | 2.9 | 28.08 | 1.23 | 10.92 | 15.22 | 107.69 |

| 9 | 12.52 | 95.29 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.59 | 3.2 | - | - | - | - | 13.18 | 98.89 |

| 10 | 8.25 | 74.39 | 0.23 | 2.51 | 3.36 | 21.49 | 0.47 | 2.97 | 2.20 | 23.57 | 14.51 | 124.94 |

| 11 | 12.32 | 121.11 | 3.97 | 23.48 | 1.21 | 4.95 | - | - | 0.22 | 0.62 | 17.72 | 150.16 |

| 12 | 23.61 | 236.84 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.53 | 5.24 | 24.14 | 242.08 |

| 13 | 24.83 | 264.66 | - | - | 0.23 | 1.67 | - | - | 0.08 | 1.62 | 25.14 | 267.96 |

| 14 | 20.98 | 203.51 | 0.33 | 1.65 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.48 | 3.50 | - | - | 21.85 | 208.88 |

Tab. 5 - Density of saplings (n ha-1) with dbh less than 7.5 cm and seedlings with height ≥ 10 cm and <130 cm in sites with age of abandonment > 12 yr.

| Site ID |

Species | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English oak | Wild cherry | Common elm | Black locust |

Hazel | European hackberry | Sweet chestnut | Hedge maple | Other species |

Total | |

| 8 | 2385 | 192 | 2739 | 220 | 10 | 527 | - | - | 336 | 6409 |

| 9 | 118 | 53 | 64 | 18 | - | - | 27 | - | - | 280 |

| 10 | 27325 | 4646 | 4377 | 10 | 1245 | 193 | - | - | 1101 | 38897 |

| 11 | 1123 | 2680 | 6154 | - | - | 142 | - | - | 1567 | 11665 |

| 12 | 402 | 2212 | - | 1580 | - | - | 891 | - | - | 5085 |

| 13 | 22092 | 2265 | 2195 | 346 | 22270 | - | 148 | 1038 | 10 | 50364 |

| 14 | 552 | 6583 | 356 | 2007 | - | - | 396 | - | - | 9894 |

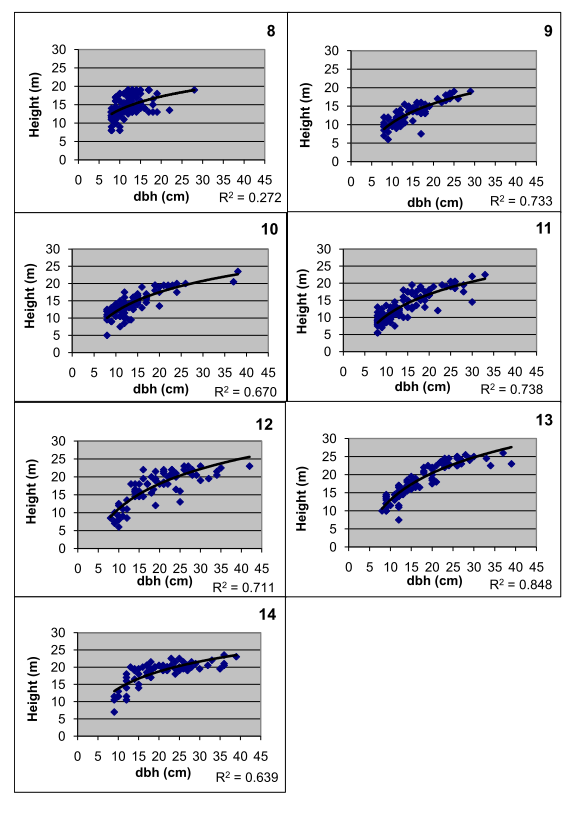

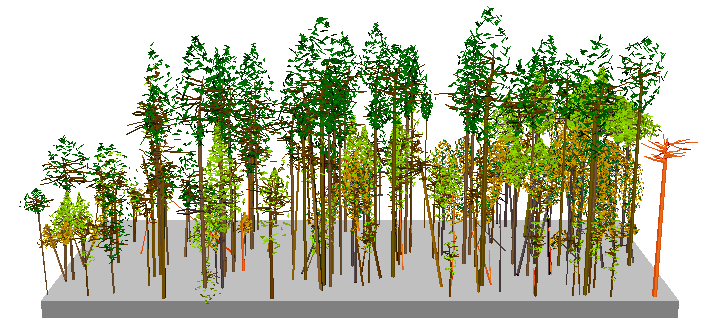

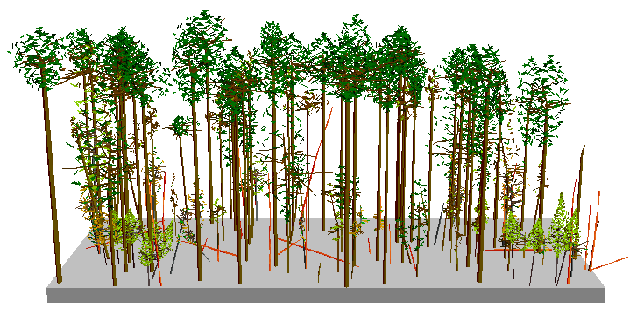

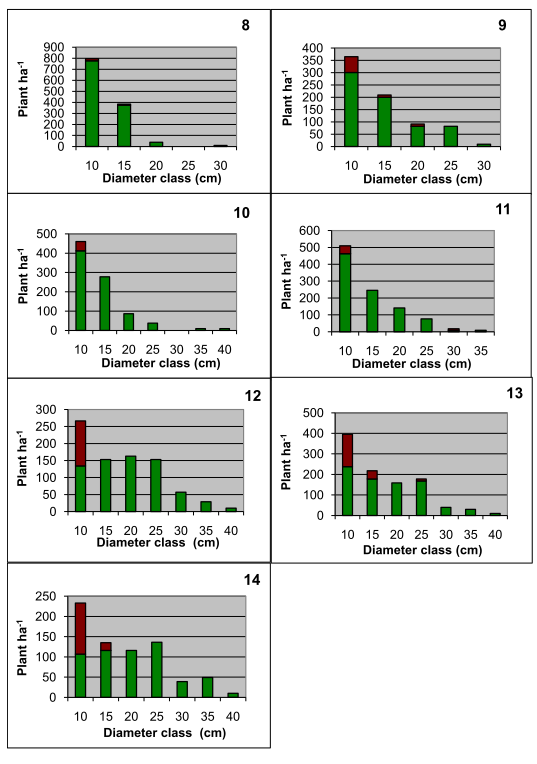

Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 illustrate, respectively, diameter distributions and height curves calculated for site 8 to 14. In stands 8 to 11 diameter distribution tends to the typical reverse J-curve of uneven-aged forests, while in the older stands 12 to 14 this distribution tends to the bell curve typical of even-aged forests. These data suggest an increase in the stand structural homogeneity along with the age of the community, probably due to the slowing of regeneration processes subsequent to soil covering by tree crowns. Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 report the perspective view realized with the SVS software for stands 11 and 12, respectively, and representative of the vertical structures occurring in the examined self-regenerated oak stands after the establishment phase. Stand 11 (Fig. 3) exhibits a stratified vertical structure with oak crowns in the uppermost canopy layer and the other hardwoods (wild cherry and common elm) in the lower layer, while stand 12 (Fig. 4) exhibits an almost uniform structure as expected from the pattern of the diameter distribution (Fig. 1).

Fig. 3 - Perspective view relative to stand 11 realized with SVS software. Dark green crowns represent English oak trees and light green crowns cherry, elm and “other species” trees; brick-red stems represent dead trees.

Fig. 4 - Perspective view relative to stand 12 realized with SVS software. Dark green crowns represent English oak trees and light green crowns trees belonging to “other species”; brick-red stems represent dead trees.

Fig. 1 - Diameter distribution in stands 8 to 14. Green and brown colours indicate alive and dead plants, respectively.

Regarding saplings with dbh less than 7.5 cm and seedlings with height ≥ 10 cm and < 130 cm, the most frequent species were oak, wild cherry, common elm and black locust (see Tab. 5). The relative abundance of these species was widely different in the various plots. It is interesting to note that other indigenous woody species such as European hackberry (Celtis australis) and Edge maple (Acer campestre) are present in some stand at the understory level.

The results obtained in stands aged between 20 and 50 years show that English oak tends to maintain the dominance within the forest community also in the stages subsequent to the early establishment of tree species. Also the most frequent accompanying species, i.e., wild cherry and common elm, are the same already observed in the younger communities.

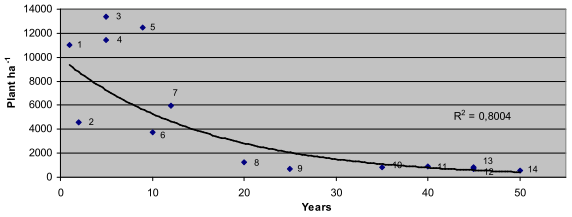

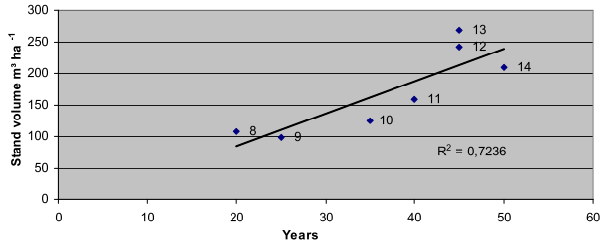

With few exceptions, black locust is still sporadic in the uppermost canopy layer, while its presence is sometimes significant in the understory, especially in older stands where the light availability under the crown of dominant trees is relatively high. Fig. 5 and Fig. 6 show, respectively, the trend in stand density and volume according to years from abandonment. As expected, stand density decreases exponentially with increasing the age of the forest community. The reduction rate tends to be more rapid in the first 20 years from abandonment (Fig. 5), when intra- and inter-specific competition is probably more intense. After 50 years from abandonment (site 14) the density is about 570 plants ha-1. Stand volume increased linearly with the years from abandonment (Fig. 6); this is consistent with the relatively young age of the examined communities and it is also indicative of their good health conditions. Demographic and volumetric values observed in the present study are similar to those reported for mixed English oak-common hornbeam stands growing in the hills along the Po river ([10]).

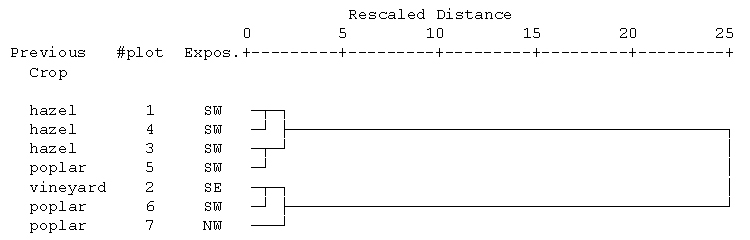

Fig. 7 and Fig. 8 show the results of the cluster analysis carried out for the stands with age <12 years and > 12 years, respectively. For the younger stands the analyses identifies two main groups, the first one including 4 plots with SW exposure and hazel or poplar plantations as previous crop, the second including 3 plots with various exposure and poplar plantations or vineyard as previous crop. For the older stands also cluster analysis separates two main groups; the first one formed by 5 plots with SW, W or S exposure, including the only older stand with poplar instead of vineyard as previous crop, the second formed by 2 plots both with SE exposure. As expected, these results confirm that previous cropping conditions as well as site exposure may exert a marked influence on the development of the studied stands. The effect of previous cropping conditions is appreciable within the younger stands, where “hazel” plots are clearly grouped (Fig. 7). The effect of site exposure appears particularly evident within the older stands, where the influence of the previous cropping conditions may be declining. In fact, in this case sites with SE aspect have been clearly separated from the other plots (Fig. 8). On the other hand, since the study area exhibits only small altitudinal variations, slope exposure can be taken as the main factor determining microclimate characteristics at the observed sites.

Fig. 7 - Results of the hierarchical cluster analysis for stands with age ≤ 12 years: dendrogram using Square Euclidean Distance method.

Fig. 8 - Results of the hierarchical cluster analysis for stands with age > 12 years: dendrogram using Square Euclidean Distance methods.

Conclusions

The analysis conducted in this study shows a strong attitude of English oak to develop well structured stands, where it is the dominant species, on former agricultural lands located in the hilly areas of south-east Piedmont. Other noble hardwoods, such as wild cherry and common elm, are frequently associated with the oak. The mean annual increment of these stands varies, approximately, from 4 to 6 m3 ha-1 year-1 at the age of 45-50 yrs. These observations coincide with those conducted by Onaindia et al. ([14]) who studied forest communities naturally regenerated on former cropland in the north-eastern France. They found, after 50 years from the abandonment of agricultural practices, the establishment of mixed hardwood stands of sessile and pedunculate oak, beech, wild cherry and rowan with good structural characteristics.

The colonisation ability showed by English oak in this study may be partly referred to the availability of acorns provided by the adult trees growing in the field edges, as well as the effective dispersion activity of small rodents and birds. However, further studies would be needed to analyze the contribution of soil physical, chemical and biological traits to these processes. Some authors have stressed the influence of soil richness on the colonization of abandoned fields by the forest vegetation ([20]), while the presence of mycorrhizae can increase the adaptability of tree species to site conditions ([2]).

On the whole, the forest stands described in this study are worthy of notice in the light of the already mentioned decline occurring in many adult oak communities in northern Italy, as well as for their potential to produce lumber and veneer logs. Therefore these stands, which usually belong to private owners, should be carefully preserved, avoiding coppicing or other irrational cuts which may favour the black locust individuals already present in the understory. At the present, moderate selective thinnings could be applied to favour the best stems providing simultaneously small wood for energy purposes. Anyway, these communities should be monitored across time in order to verify any change in species composition, structure and vegetative conditions.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

D Degioanni

Dept. AgroSelviTer, University of Turin, v. Leonardo da Vinci 44, I-10095 Grugliasco (TO - Italy)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Minotta G, Degioanni D (2011). Naturally regenerated English oak (Quercus robur L.) stands on abandoned agricultural lands in Rilate valley (Piedmont Region, NW Italy). iForest 4: 31-37. - doi: 10.3832/ifor0560-004

Paper history

Received: Apr 23, 2010

Accepted: Dec 12, 2010

First online: Jan 27, 2011

Publication Date: Jan 27, 2011

Publication Time: 1.53 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2011

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 58132

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 48845

Abstract Page Views: 3702

PDF Downloads: 4079

Citation/Reference Downloads: 23

XML Downloads: 1483

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 5497

Overall contacts: 58132

Avg. contacts per week: 74.03

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2011): 5

Average cites per year: 0.33

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Geographic determinants of spatial patterns of Quercus robur forest stands in Latvia: biophysical conditions and past management

vol. 12, pp. 349-356 (online: 05 July 2019)

Review Papers

Should the silviculture of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) stands in northern Africa be oriented towards wood or seed and cone production? Diagnosis and current potentiality

vol. 12, pp. 297-305 (online: 27 May 2019)

Research Articles

Tree-oriented silviculture: a new approach for coppice stands

vol. 9, pp. 791-800 (online: 04 August 2016)

Research Articles

Effects of mixture and management on growth dynamics and responses to climate of Quercus robur L. in a restored opencast lignite mine

vol. 15, pp. 391-400 (online: 05 October 2022)

Research Articles

Shrub facilitation of Quercus ilex and Quercus pubescens regeneration in a wooded pasture in central Sardinia (Italy)

vol. 3, pp. 16-22 (online: 22 January 2010)

Technical Reports

Effects of different mechanical treatments on Quercus variabilis, Q. wutaishanica and Q. robur acorn germination

vol. 8, pp. 728-734 (online: 05 May 2015)

Research Articles

Rapid spread of a fleshy-fruited species in abandoned subalpine meadows - formation of an unusual forest belt in the eastern Carpathians

vol. 9, pp. 337-343 (online: 20 November 2015)

Research Articles

Growth, spring phenology and stem quality of four broadleaved species assessed in provenance trials in the Netherlands - Implications for seed sourcing

vol. 18, pp. 242-251 (online: 22 September 2025)

Research Articles

Equations for estimating belowground biomass of Silver Birch, Oak and Scots Pine in Germany

vol. 12, pp. 166-172 (online: 15 March 2019)

Research Articles

Optimizing silviculture in mixed uneven-aged forests to increase the recruitment of browse-sensitive tree species without intervening in ungulate population

vol. 11, pp. 227-236 (online: 12 March 2018)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword