Approaches to classifying and restoring degraded tropical forests for the anticipated REDD+ climate change mitigation mechanism

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 4, Issue 1, Pages 1-6 (2011)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor0556-004

Published: Jan 27, 2011 - Copyright © 2011 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

Inclusion of improved forest management as a way to enhance carbon sinks in the Copenhagen Accord of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (December 2009) suggests that forest restoration will play a role in global climate change mitigation under the post-Kyoto agreement. Although discussions about restoration strategies often pertain solely to severely degraded tropical forests and invoke only the enrichment planting option, different approaches to restoration are needed to counter the full range of degrees of degradation. We propose approaches for restoration of forests that range from being slightly to severely degraded. Our methods start with ceasing the causes of degradation and letting forests regenerate on their own, progress through active management of natural regeneration in degraded areas to accelerate tree regeneration and growth, and finally include the stage of degradation at which re-planting is necessary. We argue that when the appropriate techniques are employed, forest restoration is cost-effective relative to conventional planting, provides abundant social and ecological co-benefits, and results in the sequestration of substantial amounts of carbon. For forest restoration efforts to succeed, a supportive post-Kyoto agreement is needed as well as appropriate national policies, institutional arrangements, and local participation.

Keywords

Assisted natural regeneration, Biodiversity, Climate change agreement, Forest restoration, REDD-plus, Reduced-impact logging, Silviculture

Introduction

Tropical forests support much of the Earth’s biological diversity and contribute substantially to the global economy, to local human welfare, and to the global carbon budget. Based on 109 case studies from across the tropics (TEEB Climate Issues Update 2009 as cited in [43]), if all the ecosystem services provided by tropical forests were paid for, they would generate about US$ 11.1 trillion year-1 (US$ 6 120 ha-1 ·1807 million ha), nearly equivalent to the European Union’s GDP in 2009. Unfortunately, the capacity of tropical forest to provide these services is reduced each year by deforestation ([25], [12]) as well as by degradation principally due to uncontrolled logging ([14], [4], [5], [11], [44]) and fires ([30], [40]). With regard to degradation, at least 392 million ha, or 20% of the total area of humid tropical forests, were logged during 2000-2005, and about 50% of standing humid tropical forests retained 50% or less cover as of 2005 ([4], [12]). The limited data available on carbon emissions due to forest degradation suggest that they double the 1.5-2.2 PgC yr-1 released by deforestation ([5], [17], [21], [35]). Furthermore, deforestation and forest degradation also affect 89% of all threatened birds, 83% of threatened mammals, and 91% of threatened plants (⇒ http://www.iucn.org/).

There is growing recognition of and increasing interest in generating carbon credits through reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation with enhancement of carbon sinks (REDD+), as evident by the recognition in the Copenhagen Accord adopted at the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change ([49]) in December 2009. Unfortunately, most of the international attention has focused on avoided deforestation ([24], [17]) and enhancement of carbon sinks through reforestation and afforestation ([47]) either within or outside the framework of the Kyoto Protocol. Much less attention has been paid to halting and reversing forest degradation through restoration, interventions that in addition to increased forest carbon stocks have many collateral benefits including the improved capacity of forest lands to provide other ecosystem services, support biodiversity, and contribute to social welfare. With negotiations about REDD+ intensifying, an urgent issue now is how to restore degraded forests in socially viable, environmentally acceptable, and economically cost-effective manners. Restoration strategies should be a key element of any REDD+ agreement, and therefore such strategies need to be clarified. Here we focus on the causes of degradation, propose a classification scheme that reflects the severity of degradation, and point to ways to restore degraded forests that are appropriate for the classes proposed.

Defining “Forest” for the purposes of reversing forest degradation

For the purposes of elucidating forest degradation, we adopt the UNFCCC’s definition of “forest” and the linked definitions of “deforestation” and “forest degradation” (Marrakesh Accord, Decision 11/CP.7) in full recognition of their limitations ([37], [19], [36]). Although we are particularly concerned about the lack of reference to species composition in this definitions, we take a “forest” to be an area of > 0.05 ha with tree crown cover >20% with a “tree” defined as a plant with the capacity to grow to >3 m tall. It follows then that “forest degradation” is the loss of trees and their carbon stocks down to the point that an area no longer qualifies as being forested, at which point the area is “deforested.” We further define “restoration” as management activities that help degraded forests recover their lost carbon stocks, biodiversity, and capacities to provide other goods and environmental services.

Restoration strategies and approaches

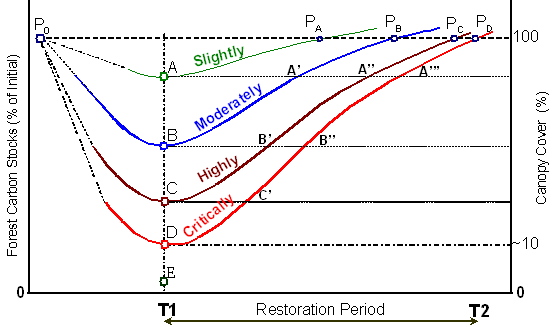

Tropical forests are degraded in ways that reduce tree cover and carbon stocks principally by indiscriminate logging ([3], [5]), fires ([32], [2]), shifting cultivation ([27]), and harvesting trees for charcoal production ([1]). To counter the effects of degradation, whatever the causes and regardless of the degrees, tree planting is often prescribed ([26], [8]). Without denying the value of tree planting where seed sources have been eliminated and degradation is otherwise severe, there are other approaches to forest restoration that are often more cost-effective and that engender fewer ecological concerns ([13], [28], [34], [38], [51], [52], [55]). By categorizing forests on the basis of degrees of degradation (Fig. 1), we can select from among these approaches with more assurance of success in terms of low financial costs, better biodiversity conservation, and broad social and environmental benefits.

Fig. 1 - Schematic diagram of different states of forest degradation and time courses for restoration. The right and left Y-axes represent different degrees of degradation expressed qualitatively as carbon stocks and percent canopy cover, respectively. (P0): pre-harvest level of primary or old growth forest; (A): only authorized trees are harvested; (B): all trees larger than the minimum diameter for cutting are harvested; (C): all marketable trees are harvested; (D): no longer forest according to forest definition adopted by the UNFCCC in 2001 (Marrakesh Accord, Decision 11/CP.7); (E): Deforested. (D to E) is eligible for reforestation or afforestation under the clean development mechanism (CDM) if deforested prior to 1989 or 1940, respectively; (A to D): degradation; (D to E): deforestation; (T1 -T2): restoration period. Negotiations to include avoiding deforestation and degradation (AE) are underway.

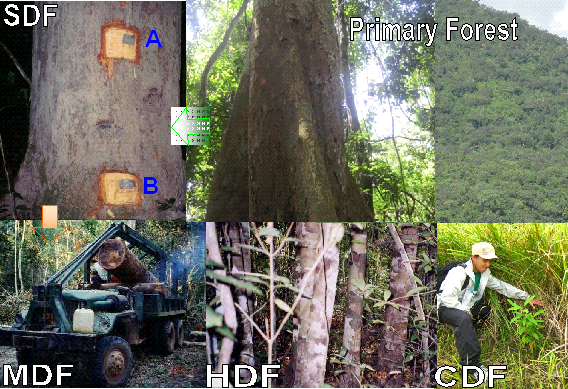

To facilitate communication about restoration strategies for forests modified from their primary, old growth, or mature condition (P0 in Fig. 1), we define the following arbitrary set of states. Forests in state A are slightly degraded but retain some trees above the minimum diameter at breast height (DBH) for legal harvesting (DBH limits for tropical countries are provided in Tab. SM1 In Supplementary material). Forests in state B are moderately degraded due to having lost their legally harvestable trees but retain many that are just smaller than the minimum cutting diameter (for legal harvest). Forests in state C are highly degraded insofar as they contain only trees much smaller than the minimum cutting diameter. Finally, forests in state D are critically degraded insofar as they have few residual trees of any size (but enough for the area to still be considered “forest” - Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 - Primary and degraded natural forests. Points A & B are tags on a mature tree that was authorized for felling in Cambodia. Tree species, DBH, block, and coupe numbers are noted on each tag. To be considered legal, the feller must cut this tree between the two tags. All felled trees without such tags are considered illegal.

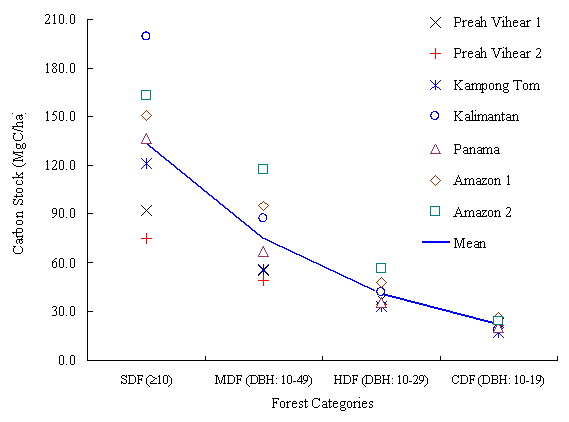

To provide rough estimates of the carbon stocks lost from forests degraded from point A to point D, data from Cambodia ([22], [23]), Indonesia ([41]), Brazil ([54], [29]), and Panama ([7]) suggest restorable losses of above-ground carbon stocks of 26.3 to 173.0 MgC ha-1 with an average of 112.4 MgC (Fig. 3 and Tab. 1). Depending on the degree of degradation, ecological characteristics of the residual species, needs and preferences of critical forest stakeholders, availability of funds, and accessibility, any of three general approaches to restoration can be appropriate, presented below in reference to these categories of degraded forest.

Fig. 3 - Above-ground carbon stocks in slightly (SDF), moderately (MDF), highly (HD), and critically (CDF) degraded forests. If CDF can be gradually restored back to the SDF, more carbon will be sequestered and stored in the forest. Due to variations in carbon stocks in various forest types across the tropics, here in the Fig. 3, we assume that SDF, MDF, HDF, and CDF contains trees with DBH≥10 cm, 10-49 cm, 10-29 cm, and 10-19 cm, respectively. With these assumptions, carbon stocks in relevant degraded forests are shown in the Fig. 3 above. Data for Preah Vihear 1 (unlogged forest in Preah Vihear province, Cambodia), Preah Vihear 2 (logged forest in Preah Vihear province, Cambodia) were adopted from Kao & Iida ([22]); data for forests in Kampong Tom province, Cambodia were adopted from Kim Phat et al. ([23]); data for forest in Kalimantan (East Kalimantan, Indonesia) were taken from Sist and Saridan (1998); data for forests in Panama were adopted from Chave et al. ([7]); data for Amazon 1 and Amazon 2 were adopted from Wellhöfer ([54]) and Nascimentoa & Laurance ([29]), respectively.

Tab. 1 - Average above-ground carbon stocks in tropical forests and percentages. Data in Tab. 1 were derived from two sites in Brazil ([54], [29]), three sites in Cambodia

| Carbon Stocks |

Category | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDF (DBH≥10 cm) |

MDF (DBH: 10-49 cm) |

HDF (DBH: 10-29 cm) |

CDF (DBH: 10-19 cm) |

|

| Above-ground carbon stocks (MgC ha-1) | ||||

| Min | 75.3 | 49.0 | 33.1 | 17.1 |

| Max | 199.4 | 117.2 | 56.6 | 26.3 |

| Mean | 134.0 | 75.2 | 41.0 | 21.6 |

| Percentage of above-ground carbon stocks (%) | ||||

| Min | 100.0 | 65.1 | 44.0 | 22.7 |

| Max | 100.0 | 58.8 | 28.4 | 13.2 |

| Mean | 100.0 | 56.1 | 30.6 | 16.1 |

Restoring slightly degraded forest (SDF, P0 to A to PA)

SDF refers to areas where timber harvesting was restricted to the legally permitted fraction of trees and only occurred in accordance with government-specified minimum cutting cycles or at longer intervals. The degradation is due to regulated harvests being more intensive and more frequent than the forest can biologically sustain, at least in the absence of silvicultural treatments, as well as due to harvesting by untrained and inadequately supervised workers operating without the aid of adequate harvest plans. The consequent reductions in carbon stocks and high-value tree species are represented by the transition from points P0 to A.

To restore SDF, we propose reductions in logging intensities, avoidance of timber harvesting from steep slopes and other environmentally sensitive areas, and lengthening of cutting cycles, as appropriate, coupled with the use of reduced-impact logging techniques and liberation treatments of future crop trees in the residual stand. These changes in management practices that serve to reduce wood waste and logging damage, and to increase the growth of future crop trees are termed reduced-impact logging plus silviculture (RIL+; refer to Tab. SM1 in Supplementary Material for explanations of terms and impacts of various logging practices in the tropics). RIL+ involves worker training, harvest planning, site preparation, directional felling, and use of appropriate equipment for log yarding. Liberation treatments might include mechanical girdling and/or killing with herbicides of non-commercial trees that overtop future crop trees, plus vine cutting to accelerate the recruitment and growth of trees that have the capacity to grow to be large. Such treatments can accelerate average tree growth by 9-27% for all tree species, and by 50-60% for future crop trees ([34], [52]); application of such treatments to a selectively logged forest in Amazonian Brazil doubled the annual rate of above-ground biomass recovery from 0.16 to 0.33 Mg C ha-1 yr-1 (see SM for calculations) during at least the initial 6 years following logging ([53]). It is important to note, however, that in Indonesia, the benefits of RIL for the residual stand disappeared where the logging intensity was > 8 trees ha-1 ([42]). Reduced felling intensities benefits not only regeneration and growth of the residual stand, but also the long-term ecological sustainability of forest management operations.

Restoring moderately degraded forest (MDF, P0 to B to PB)

In MDF, more commercially high-value trees are harvested than authorized, and excessively damaging logging practices are employed. Unfortunately, failure to enforce forest management regulations is commonplace in the tropics ([18]) and results in substantial but avoidable losses in forest carbon stocks (down to point B on Fig. 1). These logging practices result in substantial losses of commercially high-value timber species ([50]) and substantial canopy opening, which renders forests susceptible to further degradation by drought and fires. MDF still contains some intermediate size trees, some of which are reproductively mature, and some large trees with defective stems, but carbon stocks are reduced by half of that in SFD (Tab. 1). MDF requires human intervention to protect the intermediate size trees and accelerate their growth. Forests in this category could be restored by active liberation and other silvicultural treatments to enhance the growth of future crop trees (B to A’), or more passively by preventing pre-mature re-entry logging and the continued use of poor logging practices (A’ to PB).

Restoring highly degraded forest (HDF, P0 to C to PC)

In HDF even trees smaller than the legal- size limit (see Tab. SM2 in Supplementary material) and reproductively mature trees of low financial value were harvested presumably in response to strong demand for timber and fuelwood coupled with weak governance. Due to substantial canopy opening caused by excessive and repeated tree harvesting, such forests are very susceptible to further degradation by fire or grazing coupled with invasion by fire-favoring graminoids. HDF is assumed to still contain some small residual forest trees, but carbon stocks are further reduced from those in MDF (Tab. 1). Restoration of HDF requires the cessation of the causes of degradation (B’ to A”) followed by intensive liberation treatments to stimulate the growth of trees with the capacity to grow to large sizes. In forests allocated for timber production, one goal is to bring the degraded forest back to a point where there are some sound trees larger than the legal limit for harvesting (C to B’); if natural regeneration and seed trees of heavily exploited species are too scarce, enrichment planting with native species might be justified.

Restoring critically degraded forest (CDF, P0 to D to PD)

CDF corresponds to areas that barely qualify as forest under the UNFCCC’s definition and that are at the ecological threshold from which unassisted recovery is unlikely ([26]). CDFs have been stripped of most trees by over-harvesting of timber and fuelwood collection, and are often burned, overgrazed, and dominated by lianas, shrubs, giant herbs, graminoids, or other non- arboreal species, both native and exotic. At point D, the risk of further degradation and transformation to non-forest land is generally very high ([46]). CDF still contains some small trees, but carbon stocks are reduced to < 20% of SDF values (Tab. 1). Initial restoration of such areas begins with stopping the causes of degradation and allowing natural recovery processes to proceed, but such processes often need to be accelerated by various forms of more active restoration. The restoration strategies recommended for moving from point D to C’ generally involve replanting (e.g., [26], [8], and [39]), which is costly and therefore unlikely to be widely implemented. Based on various studies across the tropics (e.g., [13], [38]), “assisted natural regeneration” is likely to be more cost-effective than replanting, thus making large-scale implementation more feasible. This approach might include fire management, grazing restrictions, suppressing the growth of invasive and fire-favoring graminoids (e.g., Imperata cylindrica, Pennisetum purpureum, and Urochloa maxima), protecting naturally regenerated native tree species, weeding, fertilizing, and, if necessary, inter-planting of native or even exotic nitrogenfixing trees. Depending on geographic locations and forest conditions, another possible approach is to apply an “agro-successional” restoration approach that has proven effective with forest-dependent communities that farm ([51]). Agro-successional approach involves the use of a “taungya” system in which native tree species are inter-planted with annual crops; after two or so food crops have been harvested, the trees come to dominate the area and the farmers move to another area to repeat the process. Eventually, thinning may be needed to accelerate the growth of desired individuals, thus speeding the transition from point C’ to B”. The residues from pruning and thinning might be used for forage or fuelwood by nearby communities. With increasing forest stature, stopping the causes of degradation continues to be important as the recovery proceeds from B” to A”. Eventually, during the final restoration phase (A’” to PD), RIL+ treatments become appropriate.

Making these strategies work

A major constraint on the success of restoration interventions is the continued availability of funding, but some of the options we describe are not expensive to implement. For example, the switch from excessively destructive to reduced-impact logging reportedly ranges from having slight negative ([45]) to large positive effects on profits from timber harvesting ([20]). Depending on geographical location, season, and equipment, costs for liberation treatments by girdling of unwanted trees are likewise modest; in Bolivia they were estimated at US$ 0.21-1.04 per tree or about US$ 5.08-25.17 ha-1 ([31]; this assumes girdling of 24.2 competing trees ha-1 on average, based on [53]). The costs of restoration using assisted natural regeneration techniques are far less than enrichment planting and other conventional plantation development techniques because the costs of propagating, raising, and planting seedlings are avoided ([13], [38]). Average costs of ANR in three sites in the Philippines are approximately US$ 579 ha-1 compared to US$ 1.048 ha-1 for conventional reforestation methods ([10]). Furthermore, forests resulting from assisted natural regeneration are more biologically diverse and provide more benefits to local people than plantations. As restoration proceeds, more long-term benefits from ecosystem services and employment are expected, especially where efforts are financially supported by either the voluntary carbon market or funds from a future REDD+ agreement. Financial support for the latter is pledged at US$ 3.5 billion annually between 2010 and 2012 ([16]) and more is likely for an expected post-Kyoto implementation period between 2013 and 2020. Successful implementation of payments for ecosystem services for restoring forests in Costa Rica ([33], [6]) and in South America ([48]) provide evidence in support of the financial viability of our proposed approaches to restoration.

Effective and efficient monitoring and verification are essential to any global program that includes halting degradation and restoration among possible climate mitigation strategies. The framework we propose fits well with the latest techniques in satellite monitoring that allow direct estimation of canopy loss, recovery, and closure at a range of logging intensities ([3], [9], [15]). Moreover, the next generation of biomass-sensitive satellite sensors will soon be launched, with many more planned ([15]), which further supports the proposed strategy. Due to technological advancements and the availability of free data, the costs for monitoring carbon stocks and emissions are already as low as US$ 0.06 ha-1 in Madagascar, and US$ 0.08 ha-1 in Amazonian Peru ([5])

Conclusions

Restoring degraded tropical forests has a huge potential for mitigating global climate change by enhancing carbon stocks. Among the approaches discussed, the first is to stop the causes of degradation and allow forests to regenerate on their own. The second approach is to accelerate tree regeneration and growth through application of any of a variety of silvicultural treatments. The third general approach is to plant seeds or seedlings in natural or artificial gaps, a process often referred to as enrichment planting. To promote widespread implementation of these strategies under REDD+ initiatives, appropriate incentives, policies, institutional arrangements, and local participation are required. Since restoration takes time, long-term political commitments by participating countries will be required. REDD+ funded forest restoration will contribute to sustainable development and help secure the ecosystem services upon which billions of people depend.

Acknowledgements

We thank D. R. Foster, B. A. Colburn, K. Tanaka, B. B. Eav, M. Suwa, D. Orwig, and S. Seng for helpful comments, and S. Ouk, S. Ty, and E. Cadaweng for photos. N. Sasaki was supported through the Harvard Forest’s Charles Bullard Fellowship in Forest Research for Advanced Research. G. Asner was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

References

CrossRef | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Graduate School of Applied Informatics, University of Hyogo, 650-0044 Kobe (Japan)

Harvard Forest, Harvard University, MA-01366 Petersham (USA)

Department of Global Ecology, Carnegie Institution for Science, CA-94305 Stanford (USA)

QUEST, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, BS81RJ Bristol (UK)

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok (Thailand)

Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), P.O. Box 0113, BOCBD Bogor 16000 (Indonesia)

Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, P.O. Box 49, SE-230 53 Alnarp (Sweden)

Department of Biology, University of Florida, FL 32611 Gainesville (USA).

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Sasaki N, Asner GP, Knorr W, Durst PB, Priyadi HR, Putz FE (2011). Approaches to classifying and restoring degraded tropical forests for the anticipated REDD+ climate change mitigation mechanism. iForest 4: 1-6. - doi: 10.3832/ifor0556-004

Paper history

Received: Aug 28, 2010

Accepted: Nov 19, 2010

First online: Jan 27, 2011

Publication Date: Jan 27, 2011

Publication Time: 2.30 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2011

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 77994

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 61389

Abstract Page Views: 5085

PDF Downloads: 9576

Citation/Reference Downloads: 147

XML Downloads: 1797

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 5510

Overall contacts: 77994

Avg. contacts per week: 99.08

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2011): 39

Average cites per year: 2.60

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Commentaries & Perspectives

What happened to forests in Copenhagen?

vol. 3, pp. 30-32 (online: 02 March 2010)

Research Articles

Investigating the effect of selective logging on tree biodiversity and structure of the tropical forests of Papua New Guinea

vol. 9, pp. 475-482 (online: 25 January 2016)

Editorials

Change is in the air: future challenges for applied forest research

vol. 2, pp. 56-58 (online: 18 March 2009)

Research Articles

Effect of restoration methods on natural regeneration in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest

vol. 18, pp. 23-29 (online: 15 February 2025)

Research Articles

Impact of climate change on radial growth of Siberian spruce and Scots pine in North-western Russia

vol. 1, pp. 13-21 (online: 28 February 2008)

Research Articles

An assessment of climate change impacts on the tropical forests of Central America using the Holdridge Life Zone (HLZ) land classification system

vol. 6, pp. 183-189 (online: 08 May 2013)

Research Articles

Seeing, believing, acting: climate change attitudes and adaptation of Hungarian forest managers

vol. 15, pp. 509-518 (online: 14 December 2022)

Research Articles

Potential impacts of regional climate change on site productivity of Larix olgensis plantations in northeast China

vol. 8, pp. 642-651 (online: 02 March 2015)

Review Papers

Impacts of climate change on the establishment, distribution, growth and mortality of Swiss stone pine (Pinus cembra L.)

vol. 3, pp. 82-85 (online: 15 July 2010)

Research Articles

Predicting the effect of climate change on tree species abundance and distribution at a regional scale

vol. 1, pp. 132-139 (online: 27 August 2008)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword