The opinions of some stakeholders on the European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR): an analysis of secondary sources

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 8, Issue 5, Pages 681-686 (2015)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1271-008

Published: Mar 19, 2015 - Copyright © 2015 SISEF

Research Articles

Abstract

The EU Timber Regulation (EUTR) is the most recent effort by the European Union (EU) to curb imports of illegally sourced timber. The regulation raises important questions concerning the international timber trade. In order to successfully implement this regulation it is of paramount importance to classify the actors concerned, and examine how they regard it. The current study collects and summarizes opinion statements of stakeholders as found in different online publications. Though the problem of illegal logging and its associated trade is acknowledged by all parties, there are concerns as to whether the EUTR is the proper instrument to address this issue. Whilst some stakeholders see the EUTR as advantageous for their businesses, others see it as an impediment. Law enforcement, lack of guidance, and bureaucracy were other issues raised. The trade-off between effective legislation and ease of trade was also highlighted. Transparent and consistent application of the EUTR, with clear guidelines for exerting due diligence, should diminish the degree of possible unwanted side-effects such as trade diversion and substitution of temperate timber for tropical timber.

Keywords

Introduction

Background and objectives

The European Union (EU) is an important export market for countries with high levels of illegality and poor governance in the forest sector. Consequently, the EU initiated the EU Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade (FLEGT) action plan ([5]).

In March 2013, an additional step was taken with Regulation no. 995/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council, commonly known as the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR - [6]). This new regulation raises important questions for the future of both the European and the international timber trade. The EUTR was welcomed by many as a long awaited effort to curb illegal logging. However, particularly in the early stages of its implementation, the regulation could cause ambiguity in international timber markets, when the effects and/or the requirements are not fully understood or known by agents and stakeholders ([14]). These issues are likely to arise when each Member State (MS) transposes the new regulation into its own policy framework.

An effort has been made to disseminate information and adapt viable risk assessment and risk mitigation procedures through adequate Due Diligence Systems (DDSs) by European companies, industry federations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and MS ([9]). Following consultations with stakeholders and experts, the EC has acknowledged that certain aspects of the EUTR and its non-legislative aspects need clarification, hence producing guidance documents and supporting various information campaigns ([6], [7]). There are still some concerns among operators and traders regarding uncertainty and risk aversion ([12]).

As the EUTR was only recently introduced, assessments of the effects on timber markets of this regulation are very scarce, especially as the full impact of EUTR will be visible only once all national legal frameworks are implemented ([12]). Papers assessing agents’ and stakeholders’ interpretations of the new regulation are also scant. However, how the EUTR is understood and regarded by different stakeholders will clearly be of paramount importance for the implementation of the regulation.

Since we are dealing with a new regulation, it is likely that different actors involved in the international timber-trade (hence, directly affected by the EUTR) have not had time to fully grasp the potential impact of EUTR. The new regulation has, however, generated a lot of discussions in the media and the opinion of some stakeholders is already in the public eye. There is, however, currently a high degree of ambiguity around the new regulation in this early stage of its implementation ([14]). In order to further the understanding of how the EUTR is perceived by different stakeholders, opinion statements have been collected and summarized. These were identified in different publications found online after running an extensive desk-based search. We use frames in order to simplify certain features and relations of a complex issue, such as the EUTR, and translate them into more relevant terms ([23], [21]). This paper analyses how different stakeholders perceive, or frame, the regulatory objectives of the EUTR, on which aspects of the regulation they focus, and the perceived problems and resulting conflicts. The focus is on perceived risks, benefits and uncertainty. This study is not exhaustive in regard to perceptions of the EUTR, but rather aims to provide some contrasting examples of stakeholder perceptions, and to discuss their implications.

Policy context

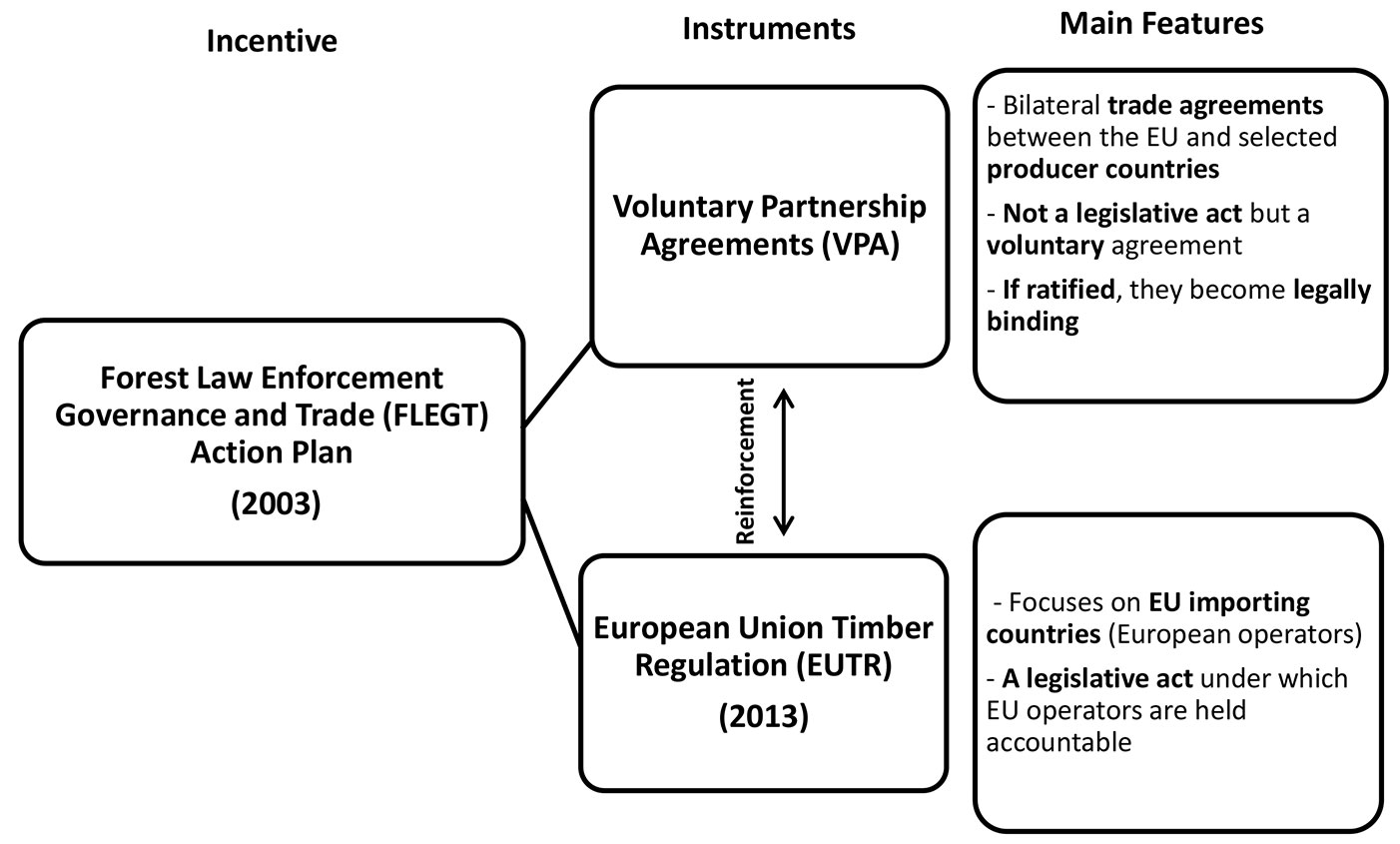

The FLEGT Action plan introduces two policy instruments: the Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPAs) and the EUTR. Both instruments address the problem of illegal logging, the first aimed at producing countries whereas the latter at EU importers. VPAs and EUTR are meant to reinforce each other (Fig. 1).

Under the EUTR, European operators (the main focus of the legislation) are held accountable for the products that they bring into the EU. Operators are encouraged to produce adequate documentation as proof for legally sourced timber ([3]). Each MS is responsible for determining how to control the legality of its imports, and how sanctions are applied if necessary ([10]).

EUTR covers a broad range of timber products (including solid wood products, flooring, plywood, pulp and paper) and sets out three main requirements for EU operators. (i) Prohibition - this prohibits placing illegally harvested timber or timber products on the EU market. (ii) DDSs - which sets the following requirements: provide access to information on imported timber (country of harvest, concession, species, sizes, quantities), implement a risk assessment procedure (evaluate the risk of occurrence of illegally harvested products) and apply risk mitigation measures and procedures. (iii) Traceability obligation - operators must keep detailed records with information on their suppliers ([2], [6]).

Under the EUTR regulation, “illegally harvested” means harvested in contravention of the applicable legislation in the country of harvest ([6]). Hence, the basis for defining illegal logging is the legislation of the producing country, considering that there is no international agreement on how to define legally harvested timber. EUTR explicitly states that timber and timber products covered by FLEGT licenses or Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) permits meet its requirements. It could be said that the EUTR creates a strong market advantage for such products. Furthermore, though certified products provide evidence of legally sourced timber, certification alone does not automatically ensure legality, unlike FLEGT or CITES licenses ([3]). Certified products may be considered as low-risk within the DDSs of companies, but it has not been determined if this approach will be accepted by law enforcement bodies ([24]). Therefore, the exact role of certification under the EUTR is yet to be determined.

Theoretical setting

Requirements imposed by a new regulation can be perceived as complex, ambiguous or indeterminate ([21]). Consequently, actors may associate complex phenomena, such as the EUTR, with certain characteristics such as safe or risky; predictable or indeterminate; important or unimportant. It is therefore essential, when assessing how a regulation may be perceived, to consider reducing its complexity and to manage uncertainty ([20]).

Through frames, certain features and relations of a complex issue (such as the EUTR) can be selected and translated into simpler, more relevant terms ([23], [21]). This aims to make a problematic situation more intelligible. A widely accepted definition of frames is offered by Entman ([11]): “To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating context, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described”.

Schön & Rein ([23]) describe frames as being created to represent beliefs, values, and perspectives held by particular interest groups. Likewise, frames have normative implications meaning that they can be used to mobilize opinions and call for solutions in the implementation process ([11], [23], [21]).

Materials and methods

Literature search

All materials for the content analysis were collected through an extensive internet desk-based search conducted during the same period as the search for scientific papers. Google (⇒ http://www.google.se) and Google Scholar (⇒ http://www.scholar.google.se) were the main tools used for accessing free-online publications. The most commonly used Google search-terms comprised: “EUTR”, “EU Timber Regulation”, “FLEGT VPA”, “Implementation EUTR”, “Impacts EUTR”, “Stakeholders and EUTR”, “Actors and EUTR”, “Risks EUTR”, “Perception EUTR” and “Understanding EUTR”. This search resulted in a considerable number of government, media, trade-federation and NGO webpages, news, reports and studies. The relevant search results were considered in their entirety and admissible links on these pages were followed as well. The final sample for the analysis comprised 15 materials relevant for content analysis, listed in Appendix 1.

Content analysis

Using qualitative content analysis, the 15 secondary sources were scanned for opinion statements to identify actors’ overall views on the EUTR. According to Bryman ([1]), content analysis is an approach for analyzing documents and texts, quantifying content in terms of predetermined categories systematically and replicable. The present content analysis merges a deductive approach (frames are theoretically derived from the literature and then coded in a standard content analysis) with a hermeneutic approach (frames are identified by providing an interpretative account of media texts linking up frames with broader cultural elements - [22]).

Two units of analysis were used: the entire document and the relevant statements quoted in the document. Each document was read through in its entirety and formal categories were identified including: author (e.g., publishing organization); date (whether published before or after EUTR was introduced); and style of the material (blog, newsfeed, article or report). This also allowed the identification and classification of the main actors in the analysis. “Actor” is defined here as a person or group that has a vested interest in the EUTR. The opinion statements of the different actors comprise the second unit of analysis. “Statement” is defined as “all claims made as either direct or indirect quotes in one article made by one person or entity” ([18]). Hence, the number of statements is the same as the number of speakers but different from the number of documents, as some documents might contain multiple actors with differing opinions.

Each of the opinion statements were read and categorized based on the general message advocated: whether they are “favorable”, “ambivalent” or “unfavorable” towards the EUTR. “Favorable” is defined here as an actor’s commendatory, generally positive and/ or encouraging disposition towards the regulation. Actors categorized under “ambivalent” gave a generally equivocal message that expresses both pros and cons, impartial and/or simply indefinable standpoints. Under “unfavorable” we list actors who displayed a general adversity, skepticism and/or criticism towards the regulation.

In line with the frame definition by Entman ([11]) outlined above, frame elements - easily and unambiguously detectable in the content analysis - were identified. Finally, an assessment was made as to how the statements were weighted and to what extent the arguments included a discussion of risk and uncertainty concerning the consequences.

Results

Classifying the actors and their roles within the EUTR

The EUTR creates a new framework within which various actors involved in the timber trade can interact. The regulation incorporates the roles of existing actors with new actors who are responsible for new tasks ([4]). For the purpose of this analysis, it is important to categorize these actors, to classify their roles and responsibilities, and to understand how they interact.

Officially, the EUTR operates with reference to six main actors ([4], [2]):

- the European Commission (EC): responsible for the effective implementation of the regulation;

- Member states (MS): each responsible for the implementation of the regulation through national competent authorities;

- Operators: the primary placers of timber or timber products on the European market;

- Traders: actors who receive timber or timber products from operators and trade on the European market;

- Monitoring Organizations (MOs): assisting operators with adequate DDSs.

The EC assigns different MOs who in turn provide services to operators by assisting with DDSs. Competent authorities, designated by each MS, are responsible for the verification of the functionality of MOs. Hence, although the EC can offer or withdraw recognition to MOs, there is no investigative authority and is therefore relying on the evaluation of competent authorities ([4]). MOs offer services to operators and past or ongoing relationships between the two parties are therefore to be considered in the implementation ([4]).

This study categorized the EC and MS as “political actors”. Both operators and traders are also referred to as “businesses” throughout the paper. In addition, MOs as well as “trade-related organizations” including timber trade federations (TTFs) and other similar organizations (profit and/or non-profit) are placed in the same category, under “trade-related organizations”. The rationale being that, although different, such organizations assist and/or support businesses in the interpretation and implementation of the EUTR.

The EUTR is under scrutiny from public opinion and media as well as from different environmental and research organizations ([26]). Various NGOs play an important role in influencing both the formulation and implementation of the EUTR; i.e., 58 international NGOs have called on the EC to adopt a regulation against illegal timber imports, but have subsequently criticized the regulation’s implementation and effectiveness ([15], [25]). Universities and research organizations, referred to as “research” throughout the paper, are also considered important and influential actors that scrutinize various aspects of the regulation.

Actors’ disposition towards the EUTR

The opinion statements were analyzed and categorized according to actors’ “general disposition” towards the EUTR. Statements from various actors are categorized in Tab. 1. The numbers in parenthesis represent the reference to the source of each opinion statement (numbers 1 to 15) listed in Appendix 1.

Tab. 1 - Actors and categorized opinion statements. Numbers in parenthesis represent the reference to the source of each opinion statement (numbers 1 to 15) listed in Appendix 1.

| Actors | Favorable | Ambivalent | Unfavorable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political actors | (1:1) | - | - |

| Businesses | - | - | (1:2); (1:3) |

| Trade-related organizations | (1:3);(1:4) | (1:5);(1:6) | (1:7) |

| NGOs | - | - | (1:8);(1:9);(1:10);(1:11) |

| Media | - | - | (1:12);(1:13);(1:14) |

| Research | - | - | (1:15) |

Not surprisingly, the results indicate a considerable heterogeneity amongst actors’ standpoints. Given the fairly recent introduction of the regulation, most actors are cautious in expressing definitive standpoints. Political actors such as the EC - which advocate good forest governance, sustainable forest management, and the necessity to combat illegal logging - appear to be the main supporters of the regulation (Appendix 1:1).

There are diverging opinions amongst business representatives. Unfavorable standpoints were found typically to come from companies which have faced public scrutiny and that have been accused of engaging in unlawful practices ([15], [12]). Business representatives generally criticized the uncertainty around the regulation indicating “the lack of operational guidance and a functional oversight mechanism” (Appendix 1:2). Others expressed concerns that the focus is mostly on legal compliance, rather than on both legality and sustainability (Appendix 1:3).

Favorable standpoints were clearly detectable in statements from North American trade-related organizations: “…one of the world’s largest hardwood exporting industries […] has a considerable stake in eradicating illegal wood from trade […] and has also been closely involved with, and fully supports, the efforts by the European Union to enforce the EU Timber Regulation from 3 March 2013” (Appendix 1:4). Other representatives state that the EUTR “could be very beneficial for Canadian producers of wood and products made of woods that are harvested in Canada, given the country’s negligible risk status” (Appendix 1:3). Although there were a vast number of statements from other trade-related organizations, few expressed a clear standpoint. However, these opinion statements generally suggest a need for improved guidance and clarification as there is “still widespread confusion” around some details of the EUTR (Appendix 1:5 and 1:6).

Some governance experts inferred that the EUTR “is likely to violate at least one substantive World Trade Organization (WTO) provision” because it “…makes the marketing of illegally logged timber a criminal offence and therefore creates a “de facto” restriction on the importation of timber…” (Appendix 1:7). Some WTO members expressed concerns regarding the regulation, representatives for Canada noted that EUTR’s “…traceability requirements could provide an unfair competitive advantage to manufacturers of forest products in the EU compared to their international competitors” (Appendix 1:7). Indonesian representatives also expressed concerns related to EUTR’s DDS requirements (Appendix 1:7).

The view of NGOs towards the EUTR is varied and interesting. International NGOs have long urged governments to adopt a timber trade legislation and many NGOs had declared their support for the EU FLEGT Action and EUTR ([16]). However, since the introduction of the EUTR, some NGOs have criticized the Regulation’s weak law enforcement, implementation, and effectiveness (Appendix 1:8; 1:9; 1:10). This has led to calls for governments to take prompt and punitive actions against operators who have been found to be breaking the law: “if any governments in the EU turn a blind eye to illegal imports, the forest destruction in areas including the Congo Basin will continue to be driven by our use of wood and associated products” (Appendix 1:11). Consequently, NGOs are concerned that weak penalties will lead to ineffective regulation.

The media has a particularly important role in providing the general public with information that may be otherwise difficult to obtain ([18]). Likewise, the media can serve as an indicator for public opinion concerning political decision makers ([17], [18]). The media also has a more insidious influence on society, influencing and sometimes distorting public opinion on certain issues ([18]). Hence, discerning the exact stand points expressed in digital mass media (websites, newsletters, and blogs) is difficult, as different media organizations may report in unbiased ways, others may be less objective and represent vested interests. Media oriented specifically at the trade sector displayed some criticism towards the regulation, regarding its impacts on trade: “the significant extra cost and complications caused by the legislation have exacerbated the continuing commercial decline of imports” (Appendix 1:12). Stark criticism and/or general adversity were advocated by some information platforms, arguing that “it is clear that the burdensome EUTR and FLEGT VPAs are not only failing timber consumers in developed nations […] but also failing to curb illegal logging itself…” (Appendix 1:13, 1:14).

Research on any related topic regarding EUTR is generally scarce, and research organizations have been somewhat reserved in expressing standpoints on the EUTR. Some researchers from international organizations have expressed criticism regarding the EUTR, in particular in regards to the impact on small scale-logging in developing countries: “…we saw this as a welcome development, but very quickly, began to realize that there could be another side to the story […] loggers now have to bear the costs of generating new forest management plans, verifying timber and issuance of a legality license that meets the requirements of the EU and US…” (Appendix 1:15).

Frame analysis

Analyzing actors’ general views towards the regulation helps outline the general frames for discussion. The problem of illegal logging and its associated trade act as a “master frame”, or a principle to which all other standpoints relate ([8], [20]). Furthermore, the ecological, economic and social risks it poses are acknowledged by all actors irrespective of whether they are favorable, ambivalent or unfavorable towards the EUTR. However, actors conceptualize the EUTR differently. Those favoring the EUTR advocate the “competitive advantage” for legal exporters, while actors that are unfavorable towards the regulation define problems such as: “competitive disadvantage”, “law enforcement”, “guidance” and “bureaucracy”. These frames are elaborated below and later summarized in Tab. 2.

Tab. 2 - Identified frames, the actors that promote them, and representative quotes (from Appendix 1).

| Frame | Actor(s) | Opinion statement example | Source (Appendix 1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive advantage | Trade-related organizations | “…could be very beneficial for Canadian producers of wood…” | (1:3) |

| Competitive disadvantage | Trade-related organizations Businesses Media Research |

“ …could provide an unfair competitive advantage to manufacturers of forest products in the EU compared to their international competitors” |

(1:7) |

| Law enforcement |

NGOs Media | “…if any governments in the EU turn a blind eye to illegal imports, the forest destruction […] will continue” |

(1:11) |

| Guidance | Businesses Trade-related organizations |

“…lack of operational guidance and a functional oversight mechanism …” | (1:2) |

| Bureaucracy | Businesses Trade-related organizations Media |

“…significant extra cost and complications caused by the legislation” | (1:12) |

- “Competitive advantage”- those favoring the EUTR, wish to see a competitive element to legal exports. Exporters from countries where illegal logging is a minor risk see the regulation as beneficial for their businesses. Hence, representatives from North American and European trade-related organizations and businesses are in favor of the EUTR. The regulation is seen as reinvigorating a legitimate forest industry which has been undermined by illegally sourced timber on the international market.

- The antithesis of the above frame is “competitive disadvantage”. Timber-exporting countries from both the Northern and Southern hemisphere have expressed concern regarding potential trade-restrictive effects of the legislation and the (unfair) competitive advantage for EU countries. However, exporters from the (perceived) more risky sources in the Global South are seen to be potentially even more disadvantaged by the regulation.

- “Law enforcement”- some actors criticized the (weak) enforcement of the regulation. This has been debated by political actors prior to the introduction of the EUTR and, as previously mentioned, recently by various international NGOs. Other concerns raised by actors are: the interpretation of legality (which differs among traders), and inconsistent (weak) penalty systems which differ between MS.

- “Guidance”- the general consensus among business representatives and trade-related organizations is the perceived lack of operational guidance for EUTR. The regulation’s requirements are ambiguous in practice. Among affected stakeholders confusion and misinterpretation of EUTR requirements seems to persist, at least of this early stage of the regulation’s implementation. Some businesses in Europe have already been found to contravene EUTR requirements.

- “Bureaucracy”- another defined problem among stakeholders was the administrative burden and associated additional costs linked with EUTR compliance. The regulation’s due diligence requirements for European operators (access to information on imported timber, risk assessment procedures, risk mitigation measures and procedures) and traceability obligations imply extra workload introducing accurate documentation that is created in a transparent and unambiguous manner. These requirements are not only tedious but they are also costly. Generating new forest management plans in order to comply with the legal standards of the EUTR, and achieving certification, also implies additional costs for loggers in developing countries.

Discussion

All of the actors considered in the analysis recognized and acknowledged the problem of illegal logging, the risks it poses, and the urgent need to combat it. However, concerns as to whether the EUTR is the best method to combat illegal logging and its associated trade is at the core of the debate, resulting in conflicting frames among actors. In general, timber-exporting countries have expressed their concerns in terms of the potential trade-restrictive effects of legislation ([13]).

While some actors see the EUTR as beneficial for their businesses, others fear the regulation could be disadvantageous. The EUTR creates a strong market advantage for products coming from low-risk countries; generally those in the northern hemisphere. On the other hand exporters from developing, high-risk countries feel disadvantaged by the regulation as it creates administrative hurdles and extra costs associated with compliance. In fact, bureaucracy-related concerns are expressed by actors from both importing and exporting countries.

It is notable that some perceived short-comings are at least theoretically addressable, i.e., they could be solved if dealt with, including enforcement and guidance issues. EUTR’s penalty system has also been criticized since each member state decides the level of fines to be applied and there is no consensus on the compatibility of fines within the EU. Creating effective penalty systems at a national level is critical to strengthen the overall effectiveness of the EUTR, as pointed out by Levashova ([19]).

Bureaucracy is a structural, or unavoidable, problem as any legislation which attempts to curb the illegal timber trade will, in all likelihood, incur some degree of bureaucracy, costs, and restrict free trade ([13]). Indeed, stricter law enforcement would be likely to increase this “shortcoming”, as the possibility to circumvent regulation would diminish. Thus, in this sense there is a trade-off between effective legislation and the ease of trade. Increased guidance (by the EC, MS governments, and MOs) should at least alleviate this bureaucratic burden.

Steps to address the lack of guidance have, in fact, been taken. Thus, following consultations with stakeholders, experts from MS, members of the FLEGT facility and the EC acknowledged that certain aspects of the EUTR needed clarification. Hence, guidance and clarification for definitions such as: “placing on the market”, “negligible risk”, and “complexity of the supply chain” were produced. Further, details were given on the “requirement for documents indicating compliance of timber with applicable legislation”, “the product scope”, “the role of third parties’ verified schemes in the process of risk assessment and risk mitigation”, “regular evaluation of a due diligence system”, “composite products”, "forest sector", and “treatment of CITES and FLEGT-licensed timber” ([7]). Apparently, additional measures to increase transparency and clarity have been called for.

There are frames that are, at least in a semantic sense, irreconcilable: competitive advantage and disadvantage respectively. Of course the purpose of the legislation is to disadvantage illegal exporters to the benefit of legal trade. However, the legislation does not intend to provide competitive advantages based on the geographical location of timber sources. To some extent at least, well thought through routines for exerting due diligence should decrease the risk of this unwanted effect of the legislation. Again, MOs play a key role here.

Understanding how stakeholders interpret and evaluate the EUTR should help avoid unwanted detrimental side-effects of the regulation on the international market. If the requirements of the EUTR are not fully understood, however, European importers may assess the risks associated with the value of the wood they want to purchase and opt for more reliable timber sources within Europe and North America. Hence, the general uncertainty around EUTR interpretation may become detrimental for tropical timber exports ([14]).

In addition, any ambiguity related to the EUTR, along with associated costs for compliance, could encourage producers in developing countries to export timber to other, more weakly regulated markets ([14]). This trade diversion could be reduced by a transparent and consistent application of the EUTR, again with clear guidelines for exerting due diligence, and by encouraging legal exports from developing countries through, for example, price premiums and/or long-term contracts. These two mechanisms are largely in the hands of market forces.

Conclusion

This research has provided a valuable first step in understanding stakeholder perceptions on the likely impact of the EUTR. As stakeholders seem to have reached consensus on the problem of illegal logging and its associated trade, there are still concerns as to whether the EUTR is the proper instrument to address this issue. Some stakeholders see the EUTR as advantageous for their businesses, others see it as an impediment and raise issues such as: law enforcement, lack of guidance and bureaucracy. This analysis highlighted the trade-off between effective legislation and ease of trade. In order to diminish the degree of possible unwanted side-effects (such as trade diversion and substitution of temperate timber for tropical timber) the implementation of the EUTR needs to build on transparency, consistency and clear guidelines for exerting viable due diligence.

An important aspect of this research has been to acknowledge the heterogeneity of actors and their different perceptions of the EUTR. It is clear that some aspects of the regulation still need clarification and specific interpretation. However, other structural aspects of the regulation need to be addressed in order to avoid conflicts of interest in the private sector with consideration at the same time, for free and equitable international trade.

In-depth, structured interviews with stakeholders would have enriched the analysis in this research project by, for example, adding to the depth of understanding of why different frames are held by different stakeholder groupings, and would possibly also have added to the number of frames identified. Unfortunately, it was not possible in this study but will be key for any future research on this issue. Nonetheless, analyzing secondary sources has still enabled the identification of different frames, and an analysis of their likely impacts on stakeholder reception of the legislation. Further, in-depth interviews will be even more fruitful in future research, once the EUTR has been fully implemented by most MS and stakeholders have had time to better grasp how the regulation affects their interests. For the time being, it is important to add to the understanding of how the regulation is interpreted by stakeholders, and presented in the media. Early detection of problems facing stakeholders will surely provide a positive impact on the EUTR’s implementation.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Peter Edwards, Ida Wallin and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission or of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

List of Abbreviations

The following abbreviations have been used throughout the text:

- CITES: Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora;

- DDSs: Due Diligence Systems;

- EC: European Commission;

- EU: European Union;

- EUTR: European Union Timber Regulation;

- FLEGT: Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade;

- LAS: Legality Assurance Systems;

- MOs: Monitoring Organizations;

- MS: Member States;

- NGOs: Non-Governmental Organizations;

- TTFs: Timber Trade Federations;

- VPAs: Voluntary Partnership Agreements;

- WTO: World Trade Organization;

- WWF: World Wide Fund.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Supplementary Material

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre (SLU), P.O. BOX 49, SE-230 53 Alnarp (Sweden)

European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), Institute for Environment and Sustainability (IES), Forest Resources and Climate Unit, v. E. Fermi, 2749 I-21027 Ispra (Italy)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Giurca A, Jonsson R (2015). The opinions of some stakeholders on the European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR): an analysis of secondary sources. iForest 8: 681-686. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1271-008

Academic Editor

Agostino Ferrara

Paper history

Received: Feb 17, 2014

Accepted: Jan 21, 2015

First online: Mar 19, 2015

Publication Date: Oct 01, 2015

Publication Time: 1.90 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2015

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 53163

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 43893

Abstract Page Views: 3216

PDF Downloads: 4624

Citation/Reference Downloads: 82

XML Downloads: 1348

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 3998

Overall contacts: 53163

Avg. contacts per week: 93.08

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2015): 9

Average cites per year: 0.82

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Confronting international research topics with stakeholders on multifunctional land use: the case of Inner Mongolia, China

vol. 7, pp. 403-413 (online: 19 May 2014)

Research Articles

Exploring the potential behavior of consumers towards transgenic forest products: the Greek experience

vol. 8, pp. 707-713 (online: 13 January 2015)

Technical Notes

Comparative analysis of students’ attitudes toward implementation of genetically modified trees in Serbia

vol. 8, pp. 714-718 (online: 08 January 2015)

Research Articles

Examining the evolution and convergence of wood modification and environmental impact assessment in research

vol. 10, pp. 879-885 (online: 06 November 2017)

Research Articles

Estimation of total extractive content of wood from planted and native forests by near infrared spectroscopy

vol. 14, pp. 18-25 (online: 09 January 2021)

Research Articles

Relevance of terpenoids on flammability of Mediterranean species: an experimental approach at a low radiant heat flux

vol. 10, pp. 766-775 (online: 02 September 2017)

Research Articles

The effects of forest management on biodiversity in the Czech Republic: an overview of biologists’ opinions

vol. 15, pp. 187-196 (online: 19 May 2022)

Editorials

SISEF and Italian forest science: thirty years of shared progress

vol. 18, pp. 194-196 (online: 05 July 2025)

Research Articles

Forest therapy in Italy: proposal of a standard procedure for validation of suitable sites

vol. 17, pp. 192-202 (online: 04 July 2024)

Commentaries & Perspectives

Key information for forest policy decision-making - Does current reporting on forests and forestry reflect forest discourses?

vol. 16, pp. 325-333 (online: 15 November 2023)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords