The feasibility of implementing cross-border land-use management strategies: a report from three Upper Silesian Euroregions

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, Volume 7, Issue 6, Pages 396-402 (2014)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor1248-007

Published: May 19, 2014 - Copyright © 2014 SISEF

Technical Notes

Collection/Special Issue: RegioResources21

Spatial information and participation of socio-ecological systems: experiences, tools and lessons learned for land-use planning

Guest Editors: Daniele La Rosa, Carsten Lorz, Hannes Jochen König, Christine Fürst

Abstract

This paper presents selected comments concerning land-use management strategies for three Czech-Polish Euroregions: Pradziad, Silesia and Cieszyn Silesia. These Euroregions comprise part of the Upper Silesia cross-border region. The main body of this study was conducted by formulating a set of questions concerning land-use strategies in the cross-border Czech-Polish Euroregions and interviewing management representatives of each Euroregion. The first section of this study concerned the need for such strategies, threats to their implementation and their content. The second section described possible methods for implementing Euroregion land-use strategies after their preparation. It is argued that Euroregion land-use management strategies should reflect such aspects as the further development of the Euroregion as a cross-border institution and should include selected issues regarding economic development and the natural environment. There are selected threats to implementing land-use strategies, such as a lack of enthusiasm among Euroregion members, the limitations of the 2014-2020 European Union budget and difficulties in achieving a single Czech-Polish development vision. Moreover, the importance of adequate Czech-Polish borderland planning tools and the role of citizens in Euroregion development are emphasised. The utility of a Euroregion scale for regional and national land-use management is discussed, using the example of the Upper Silesia cross-border region. The connection of the study results with regional land-use norms is explored, incorporating current strategic documents concerning the Czech-Polish borderland and existing legislation from both sides of the border. Some conclusions concerning appropriate cross-border landscapes land-use planning tools are outlined.

Keywords

Czech-Polish Borderland, Upper Silesia, Euroregion, Cross-border Land-use Management Strategy

Introduction

The Association of European Border Regions (AEBR) defines “Euroregion” as an organisational unit that allows and stimulates the cooperation of local governments and other public and private bodies on both sides of the border ([1]). As Perkmann & Spicer ([15]) noted, Euroregions are “organising templates for coordinating policies among contiguous local or regional authorities across national borders” (p. 12). Euroregions are dynamic constructs in which different processes are taking place, such as setting development goals, searching for new financing possibilities and expanding membership structures ([14]).

In the context of this study, the land-use management strategy should be understood as a joint document regarding the Czech-Polish borderland in the Euroregion area. It was assumed that the structure of such a document should start with an evaluation (diagnosis) of the Euroregion’s potential (location, land cover, infrastructure, demography, education, economy, analysis of existing strategic documents), followed by an analytical/strategic discussion (development scenarios, development and strategic goals, development priorities and implementation tools). Cross-border land-use management strategies are important, in that they should help to coordinate the development of the cross-border region (CBR), make transnational cooperation much smoother, and thus have a positive impact on cross-border ecosystems. On the other hand, land-use goals, interests concerning the CBRs (and Euroregions) and legislatures of the Czech Republic and Poland differ in many ways ([11]). Moreover, the administrative divisions are different on each side of the border. The cross-border land-use management strategy should strengthen the cross-border cooperation and coordinate the development of a particular CBR (Euroregion). The strategy should be one of the most important documents used in the implementation of the European Union Multiannual Financial Framework for the years 2014-2020, by facilitating the efficient use of the investment. However, little research has been carried out on the need for land-use management strategies and methods concerning such cross-border strategies in central Europe in general, and the Czech Republic/Poland in particular.

The method in this study is based on interviews conducted at the top level of management of the three studied Czech-Polish Euroregions: Pradziad, Silesia and Cieszyn Silesia. The objective of this study is to analyse the possibilities for implementing new Czech-Polish land-use management strategies in the analysed Euroregions. Additionally, this study is intended to deliver an overview of the method for developing land-use management strategies, which could be useful for each of those Euroregions.

The purposes of the study include:

- Increasing knowledge about the need for and content of cross-border land-use management strategies in relation to the three Upper Silesian Euroregions.

- Proposing a method suitable for preparing future cross-border land-use strategy documents that separately cover the three Upper Silesian Euroregions.

Cross-border land-use management strategies

The study area

The study area includes three Euroregions located inside the Upper Silesia CBR: Pradziad, Silesia and Cieszyn Silesia (from west to east). Such Euroregion members are Czech and Polish communities and districts. The three Euroregions differ in population, area, land use and economy, among other aspects (see Tab. 1).

Tab. 1 - Area, population and population density in the Pradziad, Silesia and Cieszyn Silesia Euroregions as of December 2006. Source: “Euroregiony na granicach Polski” Statistical Office of Wroclaw, Poland.

| Euroregion | Subregion | Area [km²] |

Inhabitants | Population density [persons per km²] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pradziad | CZ | 1 878 | 131 583 | 70.07 |

| PL | 4 186 | 628 238 | 150.08 | |

| Total | 6 064 | 759 821 | 125.3 | |

| Silesia | CZ | 1 116 | 224 919 | 201.54 |

| PL | 1 453 | 288 163 | 198.32 | |

| Total | 2 569 | 513 082 | 199.72 | |

| Cieszyn Silesia | CZ | 763 | 351606 | 460.82 |

| PL | 967 | 305129 | 315.54 | |

| Total | 1730 | 656735 | 379.62 | |

| Overall | CZ | 3 757 | 708 108 | 188.48 |

| PL | 6 606 | 1 221 530 | 184.91 | |

| Total | 10 363 | 1 929 638 | 186.2 |

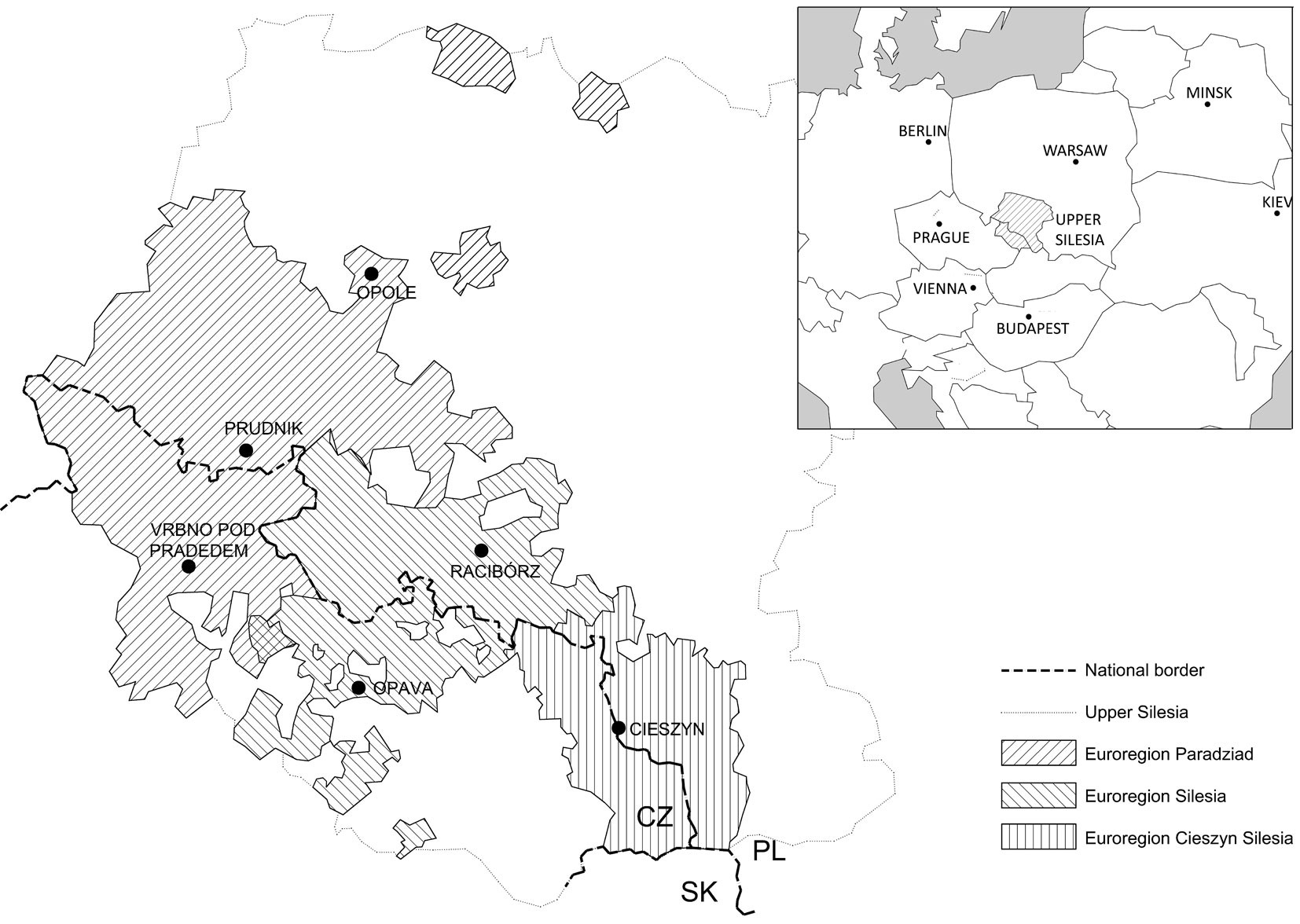

The Upper Silesia CBR, defined by its historical borders based on the study by Kordecki & Smolorz ([7]), currently covers most of the area of the Polish Slaskie and Opolskie Voivodeships and the Czech Moravskoslezský region at the level of NUTTS 2 (Fig. 1). Upper Silesia is located in central Europe at the axis of the Moravian Gate, which is formed by the depression between the Carpathian Mountains and the Sudetes (Fig. 1). Culturally and politically, the CBR was shaped by German, Czech, Slovak, Jewish and Polish influences.

Fig. 1 - Location of Pradziad, Silesia and Cieszyn Silesia Euroregions inside the Upper Silesia CBR.

Previous experiences

Paasi ([13]) raises the question of whether a “region” actually exists or is merely an idea. He stresses that a region should also be seen as an end product of a research process. Such issues seem to be important also in the context of defining CBRs and delimiting their areas. Elaborating land-use management strategies should be understood as an important element of such a research process, helping to clarify the specificity of the CBR and the strength of the idea behind it.

Beginning in the late 1980s, Czech-Polish cross-border cooperation began to grow as a result of bottom-up initiatives. The 1980s also saw an intensification of the discussion of land-use issues concerning the Czech-Polish cross-border area ([8]). The first document concerning these issues, “Coordination document for Czech-Polish borderland”, was prepared in 1991. The document was updated several times, with the currently binding version “Study of the spatial development of the Polish-Czech borderland” (“Studium zagospodarowania przestrzennego pogranicza polsko-czeskiego”), being announced in 2006. Several issues such as environmental protection, infrastructure development, tourism and the labor market were discussed between the neighboring countries ([11]).

As requested in the above-mentioned document, a Euroregion land-use management strategy can help identify local common ideas and priorities for land-use planning at the Czech-Polish borderland that would be applicable to the whole Upper Silesia. This strategy will help fulfill the goal of central European land-use planning, namely to facilitate the decentralization process - the shifting of power from central governments to the local level ([2]). Moreover, the strategies discussed therein can be helpful in achieving the strategic goals of Czech-Polish borderland development, including the enhancement of the external and internal cohesion of the Polish- Czech borderland and the protection and restore of natural and cultural resources. Such goals could be achieved by adopting a proper land-use policy based on an in-depth knowledge about each Euroregion acquired during the preparation of the local land-use strategies. In addition, these efforts would be promoted by: (i) coordinating different land-use planning initiatives on both sides of the border; (ii) formulating common Czech-Polish strategic goals for the Euroregion; and (iii) ensuring the continuity of Czech and Polish strategic planning operations.

Data collection

The study was carried out between November 2012 and February 2013 through interviews to five Euroregions management representatives (presidents and directors of the Czech and Polish parts of each Euroregion). Euroregion executives were chosen to access the viewpoints of people responsible for the Euroregion’s development.

Data were collected by a questionnaire composed of two sections (one and two). In section one, general issues about the Euroregion’s current and future cross-border land-use planning initiatives were included, with the aim of:

- investigating the need of a cross-border land-use management strategy in the Upper Silesian Euroregions;

- assessing the main impediments to implementing these cross-border land-use management strategies; and

- analyzing the types of issues related to Euroregion planned development that should be addressed in cross-border land-use management strategies.

In section one, seven general open-ended and closed questions concerning the land-use strategies in the Czech-Polish Euroregions were formulated:

- 1A. What are the most important impediments to the Euroregion’s development?

- 1B. If the Euroregion has a common Czech-Polish land-use strategy, which issues related to planned development were addressed in the strategy?

- 1C. If the Euroregion does not have a common Czech-Polish land-use strategy, which issues related to planned development should be addressed in such a document?

- 1D. What are the main threats to implementing land-use strategies for cross-border regions?

- 1E. Does the Euroregion have a common Czech-Polish land-use strategy (yes, no)?

- 1F. Are land-use strategies for cross-border regions necessary (definitely yes, yes, no, definitely no)?

- 1G. Do land-use strategies for cross-border regions have a chance of being implemented (definitely yes, yes, no, definitely no)?

In the section two of the questionnaire, the proposed land-use strategic planning method based on the project matrix (PM) was evaluated (Tab. 2). The PM represents a planning scheme and is used as a theoretical basis to discuss and address the general challenges for implementing cross-border land-use management. The main aim of the PM is to structure the preparation of a land-use management strategy in a stepwise manner. The PM consists of three modules, M1, M2 and M3, described in detail in Tab. 2. The data concerning the Euroregion landscape collected in module M1 are sorted according to the method proposed by Steiner ([19]), in which the main inventory elements are regional climate, earth, terrain, water, soil, microclimate, vegetation, wildlife and existing land use and land users. Moreover, information about the area’s history, culture, economy and demography is included. Module M2 is based on the development of expert land-use scenarios for the Euroregions. Lastly, module M3 implements the results of the previous modules and formulates the strategic priorities and goals.

Tab. 2 - The project matrix (PM).

| Module | Objective | Actions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Collecting interdisciplinary knowledge about the Euroregion cross-border landscape, which will be used as a basis for the project actions undertaken in later modules. | (1) Research into the Euroregion’s cross-border landscape, with a focus on climate, microclimate, geology, natural topography, water resources, soil, fauna and flora, current land use, infrastructure, demographic aspects, economy history and culture. (2) Consultations with public administration units and the Euroregion, preceded by an analysis of existing strategic documents. (3) Public consultation (e.g., the Delphi method). (4) Workshop for high-school students. (5) Workshop for Polish and Czech students. |

Diagnosis of the Euroregion. User-friendly and modifiable/updatable interdisciplinary set of knowledge on the Euroregion (its cross-border landscape). |

| M2 | (1) Drawing up the 2020 Euroregion development vision. (2) Four versions of the 2020 Euroregion development scenarios based on the outcomes of MODULE 1. |

(1) Drawing up guidelines for the planning tools to be developed in MODULE 3. (2) Public consultation on the development scenarios. (3) Workshop for Polish and Czech students aimed at commenting and developing the development scenarios. (4) Final version of the development scenarios. |

Guidelines for the planning tools to be developed in MODULE 3. |

| M3 | Setting priorities and strategic goals for the Euroregion. Based on outcomes of MODULE 2, developing planning tools, namely, a set of methods and actions to be used to stimulate further development of the Euroregion and further land-use planning. | (1) Formulating descriptive part of the strategy (priorities, strategic goals, action lines, planning tools).(2) Organisation of a series of consultation workshops for representatives of the public and private sector.(3) Organisation of implementation workshops for the Euroregion.(4) Publications promoting project results. (5) Establishment of an Expert Council to monitor the development of the cross-border region (similar to a think-tank). |

Euroregion land-use strategy, including a set of actions described in detail (a toolbox), intended to stimulate further development of the Euroregion. |

The purpose of this section was to:

- develop an outlook of the method to facilitate the future preparation of land-use management strategies for the three Upper Silesian Euroregions; and

- identify general challenges for land-use management in the studied area.

The section two of the questionnaire consisted of 11 open-ended and closed questions:

- 2A. How would you rate the utility of actions described in the proposed PM (insufficient, sufficient, good, very good)?

- 2B. How would you rate the logic of the modules (M1, M2, M3) proposed in the PM (insufficient, sufficient, good, very good)?

- 2C. How would you rate the idea of using a foresight method to analyze the development potential of the Euroregion (insufficient, sufficient, good, very good)?

- 2D. How would you rate the potential help given by middle-school pupils in collecting interdisciplinary data about the Euroregion and different stories about the Euroregion (“storytelling”: insufficient, sufficient, good, very good)?

- 2E. How would you rate the possible help given by university students of the Opolskie, Slaskie and Moravsko-Slezkie “voivodeships” (administrative division) in collecting interdisciplinary knowledge about the Euroregion (storytelling about the Euroregion) and in creating development scenarios (insufficient, sufficient, good, very good)?

- 2F. How would you rate the citizens’ involvement in the Euroregion development (insufficient, sufficient, good, very good)?

- 2G. How would you rate the existing brand of the Euroregion (insufficient, sufficient, good, very good)?

- 2H. How would you rate the role of creative class members in the development of towns, cities and regions (entirely irrelevant, unimportant, important, very important)?

- 2I. How would you rate the need for citizen involvement in the Euroregion’s development (entirely irrelevant, unimportant, important, very important)?

- 2J. What are the necessary actions that should be implemented to increase citizens’ involvement in the Euroregion’s development?

- 2K. Which general aspects should be used to address the scenarios prepared in module 2?

Interpretation of the results

The answers to the questions from both sections of the questionnaire are presented in Tab. 3.

Tab. 3 - Summary of all answers given in both sections of the study interviews.

| Section | Pradziad PL | Pradziad CZ | Silesia PL | Silesia CZ | Cieszyn Silesia CZ / PL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | - | (1) The lack of a clear target for bilateral cooperation | (1) The lack of funds for continuing Euroregion activity (2) Determination of “priority themes” for European Union programme period 2014-2020 in the framework of the European Territorial Cooperation, which does not correspond to real Euroregion needs (3) Different opinions between Polish and Czech partners about development goals |

(1) No proper engagement of Euroregion members in its activities (2) Fear of European Union procedures (3) Lack of new members in Euroregions and resignation of existing ones (4) Financial problems (e.g., low membership fees, microproject administration) (5) Little interest in new Czech- Polish cooperation programme for the years 2014-2020 (6) Increasing disproportion between the Czech and Polish sides of the Euroregion - better cooperation promotion on the Polish side |

(1) Availability of funds from the European Union |

| 1B | - | - | - | - | (1) Exchange of information and experiences concerning regional development, labor market (2) Cooperation in the following fields: spatial planning, prevention and liquidation of consequences of natural disasters, rescue services, economy and trade, schools and young people, tourism and further improvement of cross-border traffic (3) Solving common problems in the following fields: transport, communication, citizens’ security, ecology and environment protection (4) Cultural exchange and concern for common cultural heritage |

| 1C | (1) Transport infrastructure (2) Tourism(3) Environmental hazards and environmental protection (4) Education (5) Labor market (6) Social security (7) Health care (8) Institutional cooperation (9) Economy |

(1) Continuing cross-border cooperation of municipalities and other stakeholders(2) Building lasting friendships(3) Defining new development goals | (1) Institutional development of the Euroregion (2) Development of the Euroregion as a strong association, grouping its member communities and helping to solve their problems (3) Socio-economic development (4) Increasing competitiveness (5) Inhabitants’ quality of life |

(1) Development of the Euroregion as an institution able to raise its own funds for its activities (2) Continuous search for new financing sources (3) Involvement in projects and activities that are interesting and acceptable to all Euroregion members (4) Widening cooperation in the framework of the Euroregion beyond its management down to each member |

- |

| 1D | Lack of the Czech partners’ willingness to cooperate | “No strategy is currently implemented” | Similar to answers for question 1A and (1) No funds available for implementing the strategy (2) Organisational changes inside the Euroregion |

Same answers as for question 1A | Fluent cooperation between Polish and Czech partners comprising the Euroregion |

| 1E | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| 1F | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Yes |

| 1G | Yes | Yes | Definitely yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2A | Very good | Very good | Sufficient | Good | Good |

| 2B | Very good | Good | Good | Sufficient | Good |

| 2C | - | Very good | Good | Good | Good |

| 2D | Very good | Very good | Sufficient | Very good | Good |

| 2E | Very good | Sufficient | Good | Very good | Very good |

| 2F | Insufficient | Very good | Sufficient | Sufficient | Sufficient |

| 2G | Sufficient | Very good | Good | Good | Good |

| 2H | Very important | Important | - | Important | Important |

| 2I | Important | Very important | Important | Very important | Important |

| 2J | (1) Education in Polish and Czech schools (2) Informational meetings in different communities |

(1) Frequent and well-prepared information about bilateral cooperation and its impact on quality of life (2) Public discussion of examples of other similar “good practices” |

Public debate | (1) Raising awareness of the Euroregion (further cross-border cooperation, development of areas close to the border, communication between people from both sides of the border) (2) Public discussion of examples of other similar “good practices” from other Czech, Polish and European Euroregions |

(1) Awareness of the regional potential (2) Deepening of citizens’ knowledge about the Euroregion |

| 2K | (1) Infrastructure (2) Tourism (3) Education (4) Labor market (5) Health care |

No answers | (1) Development of the Euroregion as a strong association, grouping its member communities (2) Development of the Euroregion as an institution (3) Transport infrastructure (4) Tourism, culture, sport (5) Supporting entrepreneurship (6) Development of human resources Euroregion management |

(1) Development of the Euroregion as an institution (2) Transport infrastructure (3) Culture (4) Sport Economy/business (5) Human resources (6) Euroregion management Specifying certain actions and projects in selected strategic divisions |

(1) Natural environment (2) Waste management (3) Health care (4) Public security and emergency management (5) Economic development of the Euroregion area |

Results from section one clearly demonstrate that now is an appropriate time to examine the possibilities of implementing cross-border land-use strategies in the Euroregions analyzed. Only the Cieszyn Silesia Euroregion representative indicated that his/her institution has implemented cross-border strategic documents, namely “BORDER CROSSING - Model study of border crossings in the year 2005” and “INTERTURISM - Joint strategy for tourism development in the Silesian Beskid and Moravian-Silesian Beskid areas” (question 1E). At the time of the study the Polish association forming the Pradziad Euroregion was preparing a document entitled: “Strategy for Polish-Czech cooperation in the Pradziad Euroregion area in the years 2014-2020”. The representatives acknowledged that cross-border land-use management strategies are very necessary (question 1F), and all interviewees indicated that implementing such documents should be possible (question 1G).

According to the results, issues that the cross-border land-use strategies should address can be classified into three general categories:

- Further development of the Euroregion as a cross-border institution. The following issues were identified: strengthening cross-border cooperation between Euroregion stakeholders; identifying the issues affecting stakeholders’ development and searching for ways to solve them; seeking financing sources (question 1C).

- Economic development. The important aspects highlighted were: cross-border transport infrastructure; cross-border institutional cooperation (for instance, in the framework of cross-border clusters); the labor market; tourism and education (question 1B and 1C).

- The natural environment. The aspects deemed to be important in this area were: environmental hazards; environmental protection and preservation; liquidation of the consequences of natural disasters; inhabitants’ quality of live (question 1B and 1C).

Three main obstacles to the implementation of a cross-border land-use management strategy were identified (questions 1A and 1D):

- A lack of enthusiasm for or serious engagement with cross-border land-use planning among the Euroregion partners. This fact, combined with a fear of the European Union’s procedures, a lack of new institutional members in the Euroregions, and the resignation of existing members, should be identified as the foremost threat to cross-border land-use planning. It indicates a need for the improvement of the Euroregion’s brand and the building of trust among its members.

- The uncertainty of the European Union’s financial programming and budget for the years 2014-2020 was indicated as an impediment to cross-border land-use planning six times. This fact clearly indicates that both the process of land-use planning and further integration inside the Euroregions must be supported by proper financing.

- It is difficult to achieve a common vision of land-use planning on both sides of the border. The representative of the Polish association in the Pradziad Euroregion indicated that it is difficult even to summon the will to work on such a document. The Polish association in Cieszyn Silesia Euroregion also stressed the importance of “proper cooperation with the Czech partner”.

In section two the logic behind the proposed PM is appreciated, giving rise to the possibility of further elaboration and practical implementation of this theoretical planning scheme (questions 2A and 2B). Further considerations from the PM emphasize the following issues.

Constant development of adequate land-use strategic management tools for the Czech-Polish borderland

Results showed a marked potential for this area (question 2C). Moreover, the importance of involving different stakeholders in the early stage of the planning process was stressed by the interviewed Euroregion representatives (questions 2D & 2E). Such involvement can be implemented by planning and providing workshops for stakeholders. Cooperating with the public administration during the planning process is considered a priority, while the involvement of middle- school pupils and university students is commonly less considered. Representatives of middle-school pupils and university students could be considered a “support squad” in the planning process, providing a different perspective (different stories) about the spatial problems of the Euroregions. These support squads should be engaged in the planned workshops: (i) by gathering data and compiling fundamental information and knowledge about the Euroregion’s problems (PM, module M1); (ii) by critical reviewing and visualizing the land-use scenarios prepared (PM, module M2 - question 2K).

Engagement of Czech and Polish citizens in the Euroregion’s development

From the perspective of the Euroregion management, citizens could be more involved in the Euroregion development (question 2F). Three out of five interviewed managers rate this factor as important, and the other two as very important (question 2I). Moreover, all interviewees recognize the important role of the creative class in the regional development (question 2H). The answers to question 2J suggest several possible approaches to this purpose, all based on frequent discussions among Czech and Polish stakeholders. A possibility is to improve the Euroregion’s branding, which would encourage citizens to participate in Euroregion development in general and land-use in particular. The respondents’ answers suggest that it is important to continuously develop and improve such a brand (question 2G). Again, planning workshops are also a promising tool for increasing citizen participation.

Conclusions

Planning the CBR future

There are few important needs for land-use management in Upper Silesia CBR at the Euroregion scale. A document on the cross-border land-use management strategy does not exist in either Polish or Czech planning legislation. However, the conclusions from the Euroregion land-use management strategy should be included in national planning procedures. First, these conclusions can serve as valuable framework for land-use management at the regional level on both sides of the border and as a basis for the regular updating of national documents, being prepared with the help of local citizens and public sector representatives. Second, selected issues elaborated in the Euroregion land-use management strategy should be included in detailed land-use plans concerning Czech and Polish communities or parts thereof. During the preparation of the Euroregion land-use management strategy, Czech and Polish communities should have the chance to express their opinions about each other’s land-use plans. The process described above should be supported by the hierarchical nature of land-use planning that is well-established in the legislation, where planning at the community level takes into account the frameworks described in regional-level documents ([6]). Obviously, the differences in the land-use management/ planning legislation on each side of the border does not facilitate this implementation, but the proposed transnational and transparent process for preparing a Euroregion land-use management strategy (including adequate tools) can help overcome these difficulties.

The involvement of the Czech and Polish communities in the preparation of the requested land-use management strategy, identified as a critical issue, may help these public bodies to consider land-use management and planning form a wider, cross-border perspective, discouraging the unproductive “not in my backyard” line of thought. The involvement of Czech and Polish communities in cross-border land-use strategic management is significant in that these institutions are taking a substantial responsibility for the details of land-use planning in their areas.

Following are the issues identified in this study that can be linked to national/regional land-use norms/instruments.

Increasing Polish and Czech stakeholders’ collaboration in the land-use planning process

The European Landscape Convention emphasizes the role of participation in landscape strategic planning, the need to raise awareness of the landscape and the role of training and education ([5]). Representatives of the public sector should obviously be involved in the planning process at the earliest stage ([23]). Different methods of transdisciplinary and participative land-use strategic planning have recently been discussed (e.g., [3], [4], [17]) and criticized (e.g., [20]). Moreover, this study suggests the involvement of middle-school pupils and university students in the process via planning workshops. Those can serve as “support squads” for the overall process and can help in the identification of the planning problems, approaching from a different perspective ([18]).

Use of foresight for land-use strategic planning at the borderland

It is proposed to extend the foresight to the so-called “foresight 2.0”, in which more emphasis is placed on leadership rather than on management over the whole planning process. The process itself is also more flexible and focuses not only on problem-solving but also goal-creation ([12], [21]). The literature has indicated a significant growth in interest in scenario planning ([25]). Scenario planning approaches based on qualitative imaginary and storytelling should be introduced as a possible instrument of cross-border land-use planning ([10], [16]). Storytelling, which has been growing in importance over the last two decades, is an interesting and feasible approach (e.g., [24]). The planner’s role is to listen carefully to people’s stories and, using proper tools and methods, systematize the knowledge therein and use it as a basis for the decision-making process.

Future directions and research needs

As discussed by Lepik ([9]), Euroregions need to constantly define new development goals, cooperate with new types of members (e.g., NGOs, universities) and, above all, be aware of their financial resources. Better stakeholder involvement in land-use management could stimulate progress towards these goals. The Euroregion land-use management strategy can be used to overcome the impediments to Euroregion development mentioned in the interviews (Tab. 3). Specifically, it can be used to: (i) define clear targets for bilateral cooperation; (ii) prepare the Euroregion for the new European Union programme period (2014-2020); (iii) encourage the entrance of new members (e.g., districts and communities as well as NGOs and universities) into the Euroregion; and (iv) provide a more prominent role in national policies and participation in regional and national decision-making regarding land-use by serving as a reference for the Euroregion lobbying policy at the central governmental level on both sides of the border. In this way, the Euroregion land-use management strategy can help strengthen cross-border cooperation within all the Upper Silesia CBR in particular and other CBRs in general. All these issues should be considered as directions for future research.

Thackara ([22], p.43) writes that “dialogue and encounter are inescapable basis of trust in our relationships”. He describes the creation of trust through time as the nemawashi (“laying the groundwork”) factor. Trust must also be built between Czech and Polish stakeholders working on the cross-border land-use management strategy and planning the future of the CBR. Adequate land-use management tools and engagement of Czech and Polish citizens in the Euroregion’s development, argued in this paper, should be an element of the nemawashi factor. This factor could be the motto for further research concerning cross-border land-use management in CBRs.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by a scholarship from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education for outstanding young scientists.

I would like to thank the Euroregions representatives for their kind help in collecting research material, especially Mr Piotr Bak from the Pradziad Euroregion. I would also like to thank my colleagues Piotr Obracaj and Zbigniew Zebaty from the Opole University of Technology, Daniele La Rosa from University of Catania, Luis Inostroza from Dresden University of Technology and Jan Bondaruk from the Central Mining Institute in Katowice. The research described in this study would not have been possible without our discussions and their helpful cooperation.

Moreover, I would like to thank anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

References

Gscholar

Gscholar

Online | Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Gscholar

Authors’ Info

Authors’ Affiliation

Opole University of Technology, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Ul. Katowicka 48, 45-061 Opole (Poland)

Corresponding author

Paper Info

Citation

Spyra M (2014). The feasibility of implementing cross-border land-use management strategies: a report from three Upper Silesian Euroregions. iForest 7: 396-402. - doi: 10.3832/ifor1248-007

Academic Editor

Raffaele Lafortezza

Paper history

Received: Jan 20, 2014

Accepted: Mar 05, 2014

First online: May 19, 2014

Publication Date: Dec 01, 2014

Publication Time: 2.50 months

Copyright Information

© SISEF - The Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2014

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Web Metrics

Breakdown by View Type

Article Usage

Total Article Views: 54417

(from publication date up to now)

Breakdown by View Type

HTML Page Views: 46166

Abstract Page Views: 3152

PDF Downloads: 3689

Citation/Reference Downloads: 18

XML Downloads: 1392

Web Metrics

Days since publication: 4306

Overall contacts: 54417

Avg. contacts per week: 88.46

Article Citations

Article citations are based on data periodically collected from the Clarivate Web of Science web site

(last update: Mar 2025)

Total number of cites (since 2014): 7

Average cites per year: 0.58

Publication Metrics

by Dimensions ©

Articles citing this article

List of the papers citing this article based on CrossRef Cited-by.

Related Contents

iForest Similar Articles

Research Articles

Future land use and food security scenarios for the Guyuan district of remote western China

vol. 7, pp. 372-384 (online: 19 May 2014)

Research Articles

Confronting international research topics with stakeholders on multifunctional land use: the case of Inner Mongolia, China

vol. 7, pp. 403-413 (online: 19 May 2014)

Research Articles

Land use inventory as framework for environmental accounting: an application in Italy

vol. 5, pp. 204-209 (online: 12 August 2012)

Research Articles

Influence of site conditions and land management on Quercus suber L. population dynamics in the southern Iberian Peninsula

vol. 15, pp. 77-84 (online: 14 March 2022)

Research Articles

The effects of forest management on biodiversity in the Czech Republic: an overview of biologists’ opinions

vol. 15, pp. 187-196 (online: 19 May 2022)

Technical Reports

Deforestation, land conversion and illegal logging in Bangladesh: the case of the Sal (Shorea robusta) forests

vol. 5, pp. 171-178 (online: 25 June 2012)

Review Papers

Perspective on the control of invasive mesquite trees and possible alternative uses

vol. 11, pp. 577-585 (online: 25 September 2018)

Research Articles

Modelling the moisture status of habitats by using NDVI on the example of the Cerrado and Atlantic Forest biomes borderland (Brazil)

vol. 18, pp. 375-381 (online: 16 December 2025)

Research Articles

Does higher owner participation increase conflicts over common land? An analysis of communal forests in Galicia (Spain)

vol. 8, pp. 533-543 (online: 01 December 2014)

Research Articles

Integrating conservation objectives into forest management: coppice management and forest habitats in Natura 2000 sites

vol. 9, pp. 560-568 (online: 12 May 2016)

iForest Database Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword

Google Scholar Search

Citing Articles

Search By Author

Search By Keywords

PubMed Search

Search By Author

Search By Keyword